You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Lihui Chen.

A large body of literature found that habitual AN chewing was tightly associated with the occurrence and development of oral, esophageal, and pharyngeal cancers. In addition, many studies revealed that long-term AN usage increased the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

- areca nut

- polyphenol

- arecoline

- gut microbiota

1. Contradictory Role of Polyphenols in Cancers

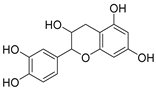

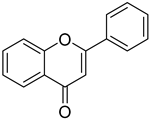

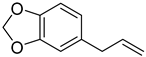

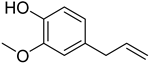

Evidence is emerging on the toxicity of the dietary polyphenols extracted by areca nut [41][1]. Major polyphenols found in areca nut (AN) are tannins, catechins, flavonoids, safrole, and eugenol, among which, tannins, safrole, eugenol, and catechins have been proven to be carcinogens. Many experimental and preclinical studies proposed that polyphenol and tannin fractions of AN had a relevant role in BQ-induced cancer development and progression, mainly attributed to their immunomodulatory properties [42,43][2][3]. For example, reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced during the autoxidation of BN polyphenols in the saliva of chewing BQ is crucial in the initiation and promotion of oral cancer [44][4]. Also, incidences of esophageal cancer have been reported to be associated with consumption of tannins-rich foods such as BN, and carcinogenic activity of tannins might be related to components associated with tannins rather than tannins themselves, suggesting a potential role of gut microbiota in tannins carcinogenicity. Epidemiological studies found that a polyphenol-rich diet protected against cancer, as well as many short-term assays revealed that AN polyphenols and tannins were not mutagenic and, in fact, even had antimutagenic effects. Some literature reported that polyphenols favored the generation of ROS [45][5]. Contrasting this, AN polyphenols were reported to be able to form conjugates with carcinogens, to trap nitrite and ROS [46,47][6][7]. The prominent polyphenols in AN and their contradictory activities are summarized in Table 1. And reported major classes of polyphenols extracted from other plants are also showed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Prominent polyphenols in AN and their activities.

| Formulas |

|---|

Table 2.

Other reported major classes of polyphenols extracted from plants and their activities.

| Polyphenols | Polyphenols | Activity | Gut Microbiota-Relevant | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representative Plant | Activity | Gut Microbiota-Dependent | Reference | ||||||

|

Catechin | ||||||||

| Resveratrol | Antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-cancer and carcinogenic activity | Yes | [ | Reynoutria japonica Houtt. and Vitis48,49][8][ | Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activity9] | ||||

| Yes | [ | 53 | ] | [14] |  |

Flavonoids | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-cancer effects, anti-bacteria and anti-virus | Yes | |

| Quercetin | Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. | Anti-virus, anti-bacterial, anti-cancer, and cardiovascular-protective effect | [ | 9,50][10 | Yes][11 | [54] | |||

| ] | [ | 15 | ] |  |

Safrole | Anti-cancer and antioxidant effects | Yes | ||

| Catechin | [ | 51 | Green tea | ][12] | |||||

| Anti-cancer, anti-virus, anti-fungi, anti-bacterial, and cardiovascular-protective effect | Yes | [ | 55 | ][16] |  |

Eugenol | Anti-bacteria and antihypertensive effect | Yes | [52][ |

| Puerarin | Pueraria lobata | Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, antihypertensive, and neuroprotective activity | 13 | Yes] |

The underlying mechanism of these observed dual, and apparently contradictory, functions of AN polyphenols and tannins in the process of BQ-induced carcinogenesis remains to be explored.

2. Bidirectional Interaction between Polyphenols and Intestinal Microbes

Polyphenols have an extremely low oral bioavailability and are almost unchanged when reaching the colon, and most of them are intensively catabolized by gut microbiota to a wide variety of new chemical structures that are often more active and better absorbed than the original phenolic compound passing hardly into the systemic blood circulation [59[20][21][22],60,61], and in turn, polyphenols could modulate oral and gut microbiota composition in host homeostasis and diseases. Several human and animal studies reported that polyphenols can elevate butyrate-producing bacterial and probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, while inhibiting opportunistic pathogenic or proinflammatory microbes. For example, bound polyphenol from foxtail millet bran can inhibit colitis-associated carcinogenesis by remodeling gut microbiota in a mice model [62][23]. The two-way interplay between microbial communities and polyphenols in the intestine is important for the latter to exert anticancer effects and might be the underlying mechanism for their contradictory and dual effects. Emerging studies have reported that diet polyphenols exert anti-obesity [63,64,65[24][25][26][27],66], anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidant effects via modulating gut microbiota. For instance, Ho, et al. found that Heterogeneity in gut microbiota drive polyphenol metabolism that influences α-synuclein misfolding and toxicity [67][28]. Mei, et al. revealed that areca nut (areca catechu L.) seed polyphenol could ameliorate osteoporosis via altering gut microbiota to increase lysozyme expression and controlled the inflammatory reaction in estrogen-deficient rats [28][29]. Studies have shown that AN could supplement polyphenols such as chlorogenic acid, (+)-catechin, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate, (−)-gallocatechin gallate, rutin, and theaflavin, which could greatly reduce high-fat diet-induced adverse effects, via easing food stagnation, eliminating indigestion, enhancing gastrointestinal motility, and regulating the activity of related enzymes [68,69][30][31]. Meanwhile, studies have revealed that AN could increase the risk of obesity and hyperglycemia. Gut microbes have the potential to explain these two opposite effects induced by AN. Despite few studies having explored the role of gut microbes in the carcinogenicity of polyphenols, there have been several studies linking gut microbes to cancer development and treatment [70,71,72,73][32][33][34][35]. For example, intestinal fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer development and facilitates tumor metastasis and chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil via its immunosuppressive effects [74,75,76][36][37][38]. Also, gut microbiota regulates the activity, efficacy, and toxicity of chemotherapy agents, such as gemcitabine [77][39], cyclophosphamide [78[40][41],79], irinotecan [80[42][43][44],81,82], and cisplatin [83,84,85][45][46][47]. Further research is required to clarify whether areca nut chewing changes the composition and function of intestinal microbes or whether intestinal microbes metabolize areca nut into carcinogens.

In recent years, there has been increasing evidence that the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) plays a major role in tumorigenesis and makes the AhR an interesting pharmacological target in cancer treatment [86,87,88,89][48][49][50][51]. Polyphenols, especially flavonoids, major constituents of AN, are the largest class of natural AhR ligands that are available for humans and animals [90,91][52][53]. Mounting evidence demonstrated that flavonoids, exhibiting AhR agonist and/or antagonist activity, are widely used for the regulation of the intestinal immune system and tumor treatment [92,93,94,95,96][54][55][56][57][58]. Dietary flavonoids are absorbed in the intestine, and the intestinal microbiota, which is deeply involved in the metabolism of them, originated from foods [97][59], and in turn, acting as AhR ligands, are able to regulate intestinal microbiota composition and intestinal immunity [98][60]. For example, tryptophan, a reported AhR ligand, could be metabolized by the certain bacterial strain, Lactobacillus bulgaricus OLL11816, to AhR-activating indoles that have shown AhR-activating potential [99,100][61][62]. However, whether flavonoids are dietary, generated by the host, or through bacterial metabolism has not been exactly established and requires further investigation.

In conclusion, few studies have reported the gut microbiome profiles in AN chewers, but some studies have shown oral microbiota composition alteration might mirror oral cancer progression in AN chewers [26,27][63][64]. However, whether microbial changes are involved in areca nut-induced oral carcinogenesis is only speculative. Further research is required to discern the clinical significance of an altered oral microbiota and the mechanisms of oral cancer development in areca nut chewers. Additional studies are necessary to clarify the precise metabolic intermediates of AN by gut microbiota or the single agent responsible for AN toxicity.

References

- Jeng, J.H.; Hahn, L.J.; Lu, F.J.; Wang, Y.J.; Kuo, M.Y. Eugenol triggers different pathobiological effects on human oral mucosal fibroblasts. J. Dent. Res. 1994, 73, 1050–1055.

- Kumpawat, K.; Deb, S.; Ray, S.; Chatterjee, A. Genotoxic effect of raw betel-nut extract in relation to endogenous glutathione levels and its mechanism of action in mammalian cells. Mutat. Res. 2003, 538, 1–12.

- Yadav, P.; Banerjee, A.; Boruah, N.; Singh, C.S.; Chatterjee, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Dakhar, H.; Nongrum, H.B.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Chatterjee, A. Glutathione S-transferasesP1 AA (105Ile) allele increases oral cancer risk, interacts strongly with c-Jun Kinase and weakly detoxifies areca-nut metabolites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6032.

- Kiraly, D.D.; Walker, D.M.; Calipari, E.S.; Labonte, B.; Issler, O.; Pena, C.J.; Ribeiro, E.A.; Russo, S.J.; Nestler, E.J. Alterations of the Host Microbiome Affect Behavioral Responses to Cocaine. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35455.

- Nair, U.J.; Friesen, M.; Richard, I.; MacLennan, R.; Thomas, S.; Bartsch, H. Effect of lime composition on the formation of reactive oxygen species from areca nut extract in vitro. Carcinogenesis 1990, 11, 2145–2148.

- Nagabhushan, M.; Bhide, S.V. Anti-mutagenicity of catechin against environmental mutagens. Mutagenesis 1988, 3, 293–296.

- Azuine, M.A.; Bhide, S.V. Protective single/combined treatment with betel leaf and turmeric against methyl (acetoxymethyl) nitrosamine-induced hamster oral carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 1992, 51, 412–415.

- Jurga, B.; Dalia, M.K. The Role of Catechins in Cellular Responses to Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2018, 20, 965.

- Huang, P.L.; Chi, C.W.; Liu, T.Y. Areca nut procyanidins ameliorate streptozocin-induced hyperglycemia by regulating gluconeogenesis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 137–143.

- Nurmeen, A.; Hamad, A. Evaluation of cytotoxicity of areca nut and its commercial products on normal human gingival fibroblast and oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123872.

- Daneel, F.; Jannie, P.; Desmond, S.; Larry, A.W. Circular dichroic properties of flavan-3,4-diols. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 174–178.

- Hu, L.; Wu, F.; He, J.; Zhong, L.; Song, Y.; Shao, H. Cytotoxicity of safrole in HepaRG cells: Studies on the role of CYP1A2-mediated ortho-quinone metabolic activation. Xenobiotica 2019, 49, 1504–1515.

- Taleuzzaman, M.; Jain, P.; Verma, R.; Iqbal, Z.; Mirza, M.A. Eugenol as a Potential Drug Candidate: A Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1804–1815.

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Butt, M.S.; Nadeem, M.; Peters, D.G.; Mubarak, M.S. Resveratrol as an anti-cancer agent: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1428–1447.

- Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B.; Sui, Z.Q.; Corke, H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): An updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 924–941.

- Singh, P.; Arif, Y.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. The role of quercetin in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 10–19.

- Zhou, Y.X.; Zhang, H.; Peng, C. Puerarin: A review of pharmacological effects. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 961–975.

- Lee, Y.M.; Yoon, Y.; Yoon, H.; Park, H.M.; Song, S.; Yeum, K.J. Dietary Anthocyanins against Obesity and Inflammation. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1089.

- Shim, G.; Ko, S.; Park, J.Y.; Suh, J.H.; Le, Q.V.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.B.; Im, G.H.; Kim, H.N.; Choe, Y.S.; et al. Tannic acid-functionalized boron nitride nanosheets for theranostics. J. Control Release 2020, 327, 616–626.

- Ozdal, T.; Sela, D.A.; Xiao, J.; Boyacioglu, D.; Chen, F.; Capanoglu, E. The Reciprocal Interactions between Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota and Effects on Bioaccessibility. Nutrients 2016, 8, 78.

- Stevens, J.F.; Maier, C.S. The Chemistry of Gut Microbial Metabolism of Polyphenols. Phytochem. Rev. 2016, 15, 425–444.

- Williamson, G.; Clifford, M.N. Role of the small intestine, colon and microbiota in determining the metabolic fate of polyphenols. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 139, 24–39.

- Yang, R.; Shan, S.; Zhang, C.; Shi, J.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Inhibitory Effects of Bound Polyphenol from Foxtail Millet Bran on Colitis-Associated Carcinogenesis by the Restoration of Gut Microbiota in a Mice Model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 3506–3517.

- Jiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lang, Y.; Li, E.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, B. Blueberry polyphenols extract as a potential prebiotic with anti-obesity effects on C57BL/6 J mice by modulating the gut microbiota. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 64, 88–100.

- Li, X.W.; Chen, H.P.; He, Y.Y.; Chen, W.L.; Chen, J.W.; Gao, L.; Hu, H.Y.; Wang, J. Effects of Rich-Polyphenols Extract of Dendrobium loddigesii on Anti-Diabetic, Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidant, and Gut Microbiota Modulation in db/db Mice. Molecules 2018, 23, 3245.

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, W.; Tian, F.; Shen, H.; Zhou, M. A combination of quercetin and resveratrol reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed rats by modulation of gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 4644–4656.

- Zhao, H.; Cheng, N.; Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Xue, X.; Wu, L.; Cao, W. Honey Polyphenols Ameliorate DSS-Induced Ulcerative Colitis via Modulating Gut Microbiota in Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900638.

- Ho, L.; Zhao, D.; Ono, K.; Ruan, K.; Mogno, I.; Tsuji, M.; Carry, E.; Brathwaite, J.; Sims, S.; Frolinger, T.; et al. Heterogeneity in gut microbiota drive polyphenol metabolism that influences alpha-synuclein misfolding and toxicity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 64, 170–181.

- Mei, F.; Meng, K.; Gu, Z.; Yun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Q.; Pan, F.; Shen, X.; Xia, G.; et al. Arecanut (Areca catechu L.) Seed Polyphenol-Ameliorated Osteoporosis by Altering Gut Microbiome via LYZ and the Immune System in Estrogen-Deficient Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 246–258.

- Song, Z.; Revelo, X.; Shao, W.; Tian, L.; Zeng, K.; Lei, H.; Sun, H.S.; Woo, M.; Winer, D.; Jin, T. Dietary Curcumin Intervention Targets Mouse White Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Brown Adipose Tissue UCP1 Expression. Obesity 2018, 26, 547–558.

- Wang, L.; Zeng, B.; Liu, Z.; Liao, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Gu, L.; Wei, H.; Fang, X. Green Tea Polyphenols Modulate Colonic Microbiota Diversity and Lipid Metabolism in High-Fat Diet Treated HFA Mice. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 864–873.

- Wong, S.H.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 690–704.

- Wu, X.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Ji, G.; Zhang, F. Microbiota transplantation: Targeting cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. 2019, 452, 144–151.

- Gori, S.; Inno, A.; Belluomini, L.; Bocus, P.; Bisoffi, Z.; Russo, A.; Arcaro, G. Gut microbiota and cancer: How gut microbiota modulates activity, efficacy and toxicity of antitumoral therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 143, 139–147.

- Wei, M.Y.; Shi, S.; Liang, C.; Meng, Q.C.; Hua, J.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Yu, X.J. The microbiota and microbiome in pancreatic cancer: More influential than expected. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 97.

- Guo, S.; Chen, J.; Chen, F.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, W.L.; Zhang, G. Exosomes derived from Fusobacterium nucleatum-infected colorectal cancer cells facilitate tumour metastasis by selectively carrying miR-1246/92b-3p/27a-3p and CXCL. Gut 2020, 71, e1–e3.

- Chen, S.; Su, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, A.; He, J.; Ge, Q.; Wang, L.; Si, J.; Zhuo, W.; Wang, L. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis by modulating KRT7-AS/KRT. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 511–525.

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Weng, W.; Guo, B.; Cai, G.; Ma, Y.; Cai, S. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil by upregulation of BIRC3 expression in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 14.

- Geller, L.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Danino, T.; Jonas, O.H.; Shental, N.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Cooper, Z.A.; Shee, K.; et al. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156–1160.

- Viaud, S.; Saccheri, F.; Mignot, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Daillere, R.; Hannani, D.; Enot, D.P.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Pittet, M.J.; et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 2013, 342, 971–976.

- Daillere, R.; Vetizou, M.; Waldschmitt, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Isnard, C.; Poirier-Colame, V.; Duong, C.P.M.; Flament, C.; Lepage, P.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Enterococcus hirae and Barnesiella intestinihominis Facilitate Cyclophosphamide-Induced Therapeutic Immunomodulatory Effects. Immunity 2016, 45, 931–943.

- Wallace, B.D.; Wang, H.; Lane, K.T.; Scott, J.E.; Orans, J.; Koo, J.S.; Venkatesh, M.; Jobin, C.; Yeh, L.A.; Mani, S.; et al. Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science 2010, 330, 831–835.

- Bhatt, A.P.; Pellock, S.J.; Biernat, K.A.; Walton, W.G.; Wallace, B.D.; Creekmore, B.C.; Letertre, M.M.; Swann, J.R.; Wilson, I.D.; Roques, J.R.; et al. Targeted inhibition of gut bacterial beta-glucuronidase activity enhances anticancer drug efficacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7374–7381.

- Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Chen, S.; Guo, S.; Yue, T.; Hou, Q.; Feng, M.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; et al. The administration of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 ameliorates irinotecan-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction and gut microbial dysbiosis in mice. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116529.

- Wu, C.H.; Ko, J.L.; Liao, J.M.; Huang, S.S.; Lin, M.Y.; Lee, L.H.; Chang, L.Y.; Ou, C.C. D-methionine alleviates cisplatin-induced mucositis by restoring the gut microbiota structure and improving intestinal inflammation. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2019, 11, 1758835918821021.

- Perales-Puchalt, A.; Perez-Sanz, J.; Payne, K.K.; Svoronos, N.; Allegrezza, M.J.; Chaurio, R.A.; Anadon, C.; Calmette, J.; Biswas, S.; Mine, J.A.; et al. Frontline Science: Microbiota reconstitution restores intestinal integrity after cisplatin therapy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 103, 799–805.

- Lee, T.H.; Park, D.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.; Oh, C.T.; Kim, J.K.; Jo, S.K. Lactobacillus salivarius BP121 prevents cisplatininduced acute kidney injury by inhibition of uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and pcresol sulfate via alleviating dysbiosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 1130–1140.

- Gluschnaider, U.; Hidas, G.; Cojocaru, G.; Yutkin, V.; Ben-Neriah, Y.; Pikarsky, E. beta-TrCP inhibition reduces prostate cancer cell growth via upregulation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9060.

- Portal-Nunez, S.; Shankavaram, U.T.; Rao, M.; Datrice, N.; Atay, S.; Aparicio, M.; Camphausen, K.A.; Fernández-Salguero, P.M.; Chang, H.; Lin, P.; et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-induced adrenomedullin mediates cigarette smoke carcinogenicity in humans and mice. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5790–5800.

- Zhang, S.; Lei, P.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Walker, K.; Kotha, L.; Rowlands, C.; Safe, S. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor as a target for estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer chemotherapy. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2009, 16, 835–844.

- Ambolet-Camoit, A.; Bui, L.C.; Pierre, S.; Chevallier, A.; Marchand, A.; Coumoul, X.; Garlatti, M.; Andreau, K.; Barouki, R.; Aggerbeck, M. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin counteracts the p53 response to a genotoxicant by upregulating expression of the metastasis marker agr2 in the hepatocarcinoma cell line HepG. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 115, 501–512.

- Flaveny, C.A.; Murray, I.A.; Chiaro, C.R.; Perdew, G.H. Ligand selectivity and gene regulation by the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor in transgenic mice. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 75, 1412–1420.

- Zhang, S.; Qin, C.; Safe, S.H. Flavonoids as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: Effects of structure and cell context. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1877–1882.

- Xue, Z.; Li, D.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, X.; He, Y.; Kou, X. Mechanisms and therapeutic prospects of polyphenols as modulators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1414–1437.

- Shinde, R.; McGaha, T.L. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: Connecting Immunity to the Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 1005–1020.

- Roman, A.C.; Carvajal-Gonzalez, J.M.; Merino, J.M.; Mulero-Navarro, S.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.M. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the crossroad of signalling networks with therapeutic value. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 185, 50–63.

- Chen, A.Y.; Chen, Y.C. A review of the dietary flavonoid, kaempferol on human health and cancer chemoprevention. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 2099–2107.

- Polozhentsev, S.D.; Reiza, V.A.; Malinskii, D.M.; Lebedev, M.F. . Sov. Zdravookhr. 1989, 1, 50–53.

- Murota, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Uehara, M. Flavonoid metabolism: The interaction of metabolites and gut microbiota. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 600–610.

- Schanz, O.; Chijiiwa, R.; Cengiz, S.C.; Majlesain, Y.; Weighardt, H.; Takeyama, H.; Förster, I. Dietary AhR Ligands Regulate AhRR Expression in Intestinal Immune Cells and Intestinal Microbiota Composition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3189.

- Takamura, T.; Harama, D.; Fukumoto, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Shimokawa, N.; Ishimaru, K.; Ikegami, S.; Makino, S.; Kitamura, M.; Nakao, A. Lactobacillus bulgaricus OLL1181 activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway and inhibits colitis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 817–822.

- Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Chai, J.N.; Tianero, M.D.; Di Luccia, B.; Ahern, P.P.; Merriman, J.; Cortez, V.S.; Caparon, M.G.; Donia, M.S.; Gilfillan, S.; et al. Lactobacillus reuteri induces gut intraepithelial CD4(+)CD8alphaalpha(+) T cells. Science 2017, 357, 806–810.

- Hernandez, B.Y.; Zhu, X.; Goodman, M.T.; Gatewood, R.; Mendiola, P.; Quinata, K.; Paulino, Y.C. Betel nut chewing, oral premalignant lesions, and the oral microbiome. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172196.

- Zhong, X.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y. Oral microbiota alteration associated with oral cancer and areca chewing. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 226–239.

More