At present, with the continuous research on anti-tumor immunity, immunotherapy–especially with respect to immune checkpoint inhibitors led by anti-PD-1/PD-L1–has become a widely accepted therapy in clinical practice

[1]. At this stage, immunotherapy targeting immune cells, particularly that which focuses on T cells, has emerged as a powerful weapon against tumors, and includes immune checkpoint blockades, adoptive cellular therapies, and cancer vaccines

[2]. However, a large number of cancer patients do not benefit from this novel and effective treatment. This is mainly due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and the diversity of the immunomodulatory network

[3]. The intensity of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and the mutational burden of the tumor have been considered as biomarkers for determining the population that is effective in immunotherapy. In addition, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) have been shown to be highly correlated with efficacy, but they have not been used as a predictive biomarker for patient selection

[4][5][4,5]. Although the efficacy of immunotherapy combined with other treatments in populations without PD-L1 expression has been demonstrated in previous studies

[6], the mechanisms need to be explored further. Some studies have shown that tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs)–defined by clusters of immune-infiltrating cells–in tumors or the tumor periphery are mostly correlated with better prognosis in patients, whether or not PD-L1 is expressed

[7]. A TLS is a spatial structure composed of B cells in the center, surrounded by T cells and a variety of immune cells and immune-related cells, with no envelope covering its surface. Similar to SLOs, TLSs regulate the immune microenvironment by recruiting circulating immune cells and enhancing local immune action. As sites for the generation of circulating immune cells that control tumor progression and better prognosis, independent of the expression of PD-L1, TLSs hold great prospects and potential. In order to better understand what kind of TLSs may benefit patients and the role of TLSs in tumor immunotherapy, in this

pape

ntry researchersr we summarize the overall roles of TLSs and their components, as well as clinical trials using TLSs as markers and related research in recent years.

2. The Function of TLSs as Complete Structures

Tertiary lymphoid structures, which are also known as ectopic lymphoid organs, are aggregates of immune cells that appear in tissues where no secondary lymphoid organ (SLO) exists. According to a large number of studies in the past year, TLSs are usually observed at inflammatory sites in response to autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, organ transplantation, inflammatory disorders, and tumors. There is mounting evidence suggesting their formation is closely related to immune responses mediated by exposure to chronic inflammation. TLSs usually lead to a persistent autoimmune response with a negative impact on subsequent pathological conditions in other diseases

[8][9][10][8,9,10]. However, TLSs are still considered to be a favorable prognostic and predictive factor in tumors

[11][12][13][14][15][16][11,12,13,14,15,16]. TLSs are able to provide local anti-tumor immunity, independent of SLOs, which has been demonstrated in the absence of SLOs in mouse models

[17].

At present, TLSs can be detected by methods including H&E, immunohistochemistry (IHC), multiplex immunofluorescence (IF) techniques, various chemokines/cytokines of TLS detection, and related gene expression

[18]; however, there is no TLS detection and counting criterion that is widely accepted in clinical practice. On H&E-stained slides, TLSs were identified morphologically as distinct ovoid lymphocytic aggregates presenting HEV and/or a germinal center

[19]. A TLS has been described in detail as a germinal center consisting of CD20+B cells and plasma cells, surrounded by CD3+T cell zones with DCs and peripheric HEVs, resembling SLOs in formation, structure, and function

[18][20][18,20]. Therefore, SLOs are the most suitable model by which to better understand how TLSs are formed; SLOs have been proven to have many similarities with TLSs in preclinical mouse models

[21]. The genesis of TLSs results from a highly ordered sequence of events involving interactions between hematopoietic and non-lymphoid stromal cells, in which cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and survival factors including CXCL13, CXCL12, CCL19, CCL21, the tumor necrosis factor superfamily, IL-6, and IL-7

[22][23][22,23] play key roles as molecular components

[24]. Additionally, one study recently demonstrated that TGF-β-mediated silencing of STAB-1 that induces Tfh cell differentiation and the subsequent formation of intra-tumor TLSs further sheds light on the origin of TLSs in complex TME

[25].

TLS density, location, and maturation have been demonstrated to have close associations with favorable clinical outcomes

[19][26][27][28][29][30][19,26,27,28,29,30], including disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). TLS density is correlated with germinal center formation and the expression of genes associated with adaptive immune response, and it is a strongly independent prognostic marker in lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and breast cancer

[31][32][33][34][31,32,33,34]. There have also been opposing observations that TLS density has no or limited relation with better survival

[35][36][35,36]. In patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the density of TLSs in tumors became similar, losing its predictive effect

[27]. The high TLS density in tumors is usually associated with high TIL density as well as with the expression of PD-1/PD-L1, suggesting the potential benefit from immunotherapies

[37][38][37,38]. However, it was found that a subtype of glioma with high immune infiltrations and TLSs resulted in poor prognosis. This may be because the beneficial effect of TLSs could be reduced in patients with higher immunosuppressive cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MSDC)

[39]. With regard to TLS location, many studies have reported the persistence of TLSs in tumors or peritumors. Peritumoral TLSs often play a favorable role in prognosis in lung cancer

[27], pancreatic cancers

[40], CRC

[41], oral squamous cell carcinoma

[42], metastases of melanoma

[43], and ovarian cancer

[44], but they are also associated with poor prognosis and invasive metastasis in breast cancer

[19]. Intra-tumoral TLSs are described as a favorable maker in lung cancer

[45] and HCC

[46]. With regard to TLS maturation, according to the works of Silina et al., the development of tumor-associated TLSs follows sequential stages of maturation: (1) early TLSs (E-TLSs), T cells, B cells, and CXCL13-expressing perivascular cells gather into clusters without FDC; (2) primary follicle-like TLSs (PFL-TLSs), i.e., TLSs containing FDC without GCs; 3) secondary follicle-like TLSs (SFL-TLSs), i.e., TLSs are analogous to the SLO follicles

[27]. E-TLSs lacking germinal centers may favor immune evasion and progression to full-blown HCC in liver precancerous lesions. The presence of mature TLSs is also associated with an improved objective response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival independently of PD-L1 expression status and CD8+ T-cell density

[7]. In general, TLSs vary widely in density, location, maturation, and components, as well as in their proportions in different individuals, and this high heterogeneity needs better classification and further research for application in clinical practice.

As mentioned above, although TLS plays a positive role in anti-tumors immunity in the vast majority of reports, there are still some studies that report its negative effects. Peri-cancerous TLS was considered a major contributor to adverse effects on prognosis

[19]. One study showed the abundance of Treg cells in intra-tumoral TLS increased significantly with the increase in peri-cancerous TLS regions

[47]. This suggested that Treg cells in peri-cancerous TLS may be responsive to suppression of the anti-tumor response and the interplay between peri-cancerous and intra-tumoral immune cells. An additional prognostic disadvantage was immature TLS. In immature TLS, the types and numbers of immune cells vary greatly, such as B cells, which were low and produced immunosuppressive cytokines in immature TLS

[48]. In addition, TLS was found to be associated with immune-related adverse events

[49].

3. The Role of TLS Components in Tumor-Specific Immune Response

TLSs, as important factors associated with a series of anti-tumor specific immune responses, play multiply significant roles in tumor progression and suppression in TME. Earlier research has suggested that the double roles of each TLS might differ depending on their composition

[50]. The cellular components of TLSs affect the function of the anti-tumor immune response in different types of cancer. Therefore, to further understand the prognostic value of TLSs and their dual role in anti-tumor immunity, differences in TLS components and their ratios need to be considered. Next,

rwe

searchers focus on five major components of TLSs: T cells, B cells, DCs, HEVs, and TLS-associated cells (

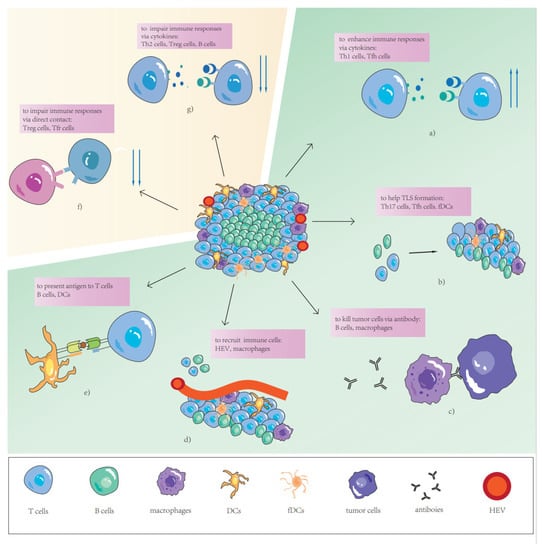

Figure 1).

Figure 1. The role of different TLS components. (a) Th1 cells and Tfh cells produce cytokines to enhance immune responses. (b) Th17 cells, Tfh cells, and fDCs help TLS formation via cytokines or contact. (c) Plasma cells kill tumor cells via antibody-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis (ADCP) and or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). (d) Circulating immune cells migrate into TLSs via HEVs or macrophage induction. (e) B cells and DCs present antigens to T cells. (f) Treg cells and Tfr cells impair immune responses via direct contact. (g) Th2 cells, Treg cells and B cells produce cytokines to impair immune responses.

3.1. T Cells

Naïve CD3+T cells recruited by TLSs become activated, proliferate, and differentiate based on the local tumor antigen presentation, cytokine milieu, and expression of costimulatory molecules, to result in several subsets of effector CD4+ T helper cells (Th), effector CD8+ T cytotoxic cells (CTL), and a small amount of memory T cells (Tm). The subtypes of Th cells can activate anti-tumor immunity directly or stimulate T cytotoxic cells to activate anti-tumor immunity, and some specific species can also inhibit immune cells from activity. Resembling SLOs, different subtypes of Th cells and their secreting cytokines, as well as chemokines, have mutual inhibition competition in TLSs. According to digital spatial-profiling data, T cells in tumors without TLSs had a dysfunctional molecular phenotype, which suggests that TLSs play a key role in the immune microenvironment by conferring distinct T cell phenotypes

[15].

CD4+Th-1 cells are characterized by T-bet and production of IL-2, interferon γ (IFNγ), and so on. IFN-γ is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays an important role in anti-tumor immunity by directly mediating tumor rejection and recruiting and activating innate and adaptive immune cells in TME. IL-2, which promotes T cell proliferation and maintains its functional activity, has been used in patients with metastatic melanoma and kidney cancer. The production of these cytokines by Th-1 cells is crucial to anti-tumor immunity mediated by CD8+ T cells. However, interestingly, a previous study showed that high infiltration in Th-1 cells and high numbers of CD20+ B-cell follicles–both of them usually aggregating with structures considered as TLSs–were associated with better relapse-free survival in gastric cancer

[51]. The densities of Th-1 cells and T follicular helper cells (Tfh) are both reported to be positively correlated with overall survival (OS) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma

[52], and the latter are vital to B cells during germinal center (GC)-reactions in SLO

[53]. This means that TLSs may exert an anti-tumor immune function through allowing T cell and B cell coordination. Although there is increasing evidence confirming the importance of humoral immunity in TLSs, a high ratio of Th-2 cells in TLSs, which are regarded as promoters of humoral immunity, was identified as a remarkably independent risk factor for recurrence in CRC, and the ratio increased in metastatic tumors in previous studies

[50]. Although direct evidence that Th-2 cells can suppress anti-tumor immunity and promote tumor progression is lacking for TLSs, findings regarding the TME suggest that Th2 cells can produce IL-4 and IL-13, with the former increasing the expression of epidermal growth factor to enhance neoplastic extravasating into the circulation, and the latter inhibiting the CD8+ cytotoxic T cell (CTL) response indirectly by increasing TGF-β production by myeloid cells in the tumor

[54][55][54,55].

3.2. B Cells

B cells are mostly located in the germinal centers of TLSs in human cancers. They are characterized by different markers depending on their maturation degree such as CD19, CD20, and CD21. B cells and plasma cells (mature B cells) make up the germinal centers in TLSs and are considered one of alternative markers of TLSs. In the beginning of the era of immune therapy, B cells were reported to potentially favor tumor occurrence, progression, and spread

[56][72]. In a variety of mouse models, complement and antibodies produced by plasma cells were found to contribute to chronic inflammation

[57][73], and immune complexes might activate macrophages to produce vascular endothelial growth factors that could increase angiogenesis

[58][74]. In addition, B cells were considered to be able to produce suppressive cytokines such as IL-10, inhibiting T cell responses

[59][75]. With the development of tumor immunity, increasing research has suggested that an abundance of B cells, especially in TLSs, has been positively correlated with prognosis and the efficacy of immune therapy in human cancers in recent years

[60][61][62][63][64][76,77,78,79,80]. Although the true mechanisms by which B cells in TLSs enhance or directly develop anti-tumor immune responses still need to be explored,

rwe

searchers can learn from how B cells influence immunity in SLOs. Just like in SLOs, B cells can recognize neoantigens via B cell receptors and then allow antigen binding with major histocompatibility complex-1 (MHC-1) or major histocompatibility complex-2 (MHC-2), then the presentation to T cells directly or to dendritic cells (DC) to activate T cells in TLSs

[65][66][67][81,82,83]. This method of antigen presentation is very effective in eliciting a T cell response with a low tumor mutation load and amplifying an immune response with high tumor mutation load

[56][72] because B cells may make contact with tumor cells at a very close distance, and immune complexes formed by combination of antibodies and neoantigens can be internalized by DCs. This means that the quantity of antigens necessary to induce a T cell response is much lower than direct antigen presentation by DCs. In addition, they are able to produce antibodies that can recognize shared tumor antigens, not patients’ specific tumor antigens that are almost recognized by T cells

[68][84]. Tumor cells are damaged by these antibodies through antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and/or antibody-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis (ADCP). These reactions are mediated by fragment crystallizable (Fc) portions of tumor-specific antibody binding to Fc receptors of effector cells or complements. Similarly, there are differences between B cells with different functional markers in prognosis, such as OS being longer for TLSs with low fractions of CD21+ B cells, and shorter for those with a low activation-induced deaminase (AID)+ fraction of B cells

[69][85]. B cells will gradually decrease the expression of CD21 and increase the expression of AID in their mature process and migrate to the GCs. AID supports immune system diversification and acts in antigen-stimulated B cells by allowing antigen-driven immune globulin diversification. When AID is activated with appropriate cytokine signals in the B cells, interaction can occur with DCs and Tfr cells in GCs

[70][86]. Many studies have indicated that B cells play a direct or indirect important immune role in TLSs. However, a previous study on hepatocellular carcinoma showed that B cell-rich TLSs constitute a specific niche by which to protect tumor progenitors and produce lymphotoxin β to support the growth of tumor cells

[71][87].

3.3. Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a diverse group of professional antigen-presenting cells, with key roles in the initiation and regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses

[72][88]. DCs are crucial to TLS formation

[73][89] and maintenance, which has been validated in mouse models

[74][90]. LAMP+ DCs (mature DCs) are considered to be believable markers of TLSs in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), because they are almost exclusively found in these structures in this cancer type

[18]. However, some research on other cancers has shown that LAMP+DC was detected in non-TLS tumor lesions

[64][75][76][80,91,92]. Another previous study suggested that the LAMP+DC density was correlated with favorable clinical outcomes (overall, disease-specific, and disease-free survival) and the TIL density (in particular, Th-1 cells) was significantly decreased in tumors poorly infiltrated by LAMP+DCs

[45]. LAMP+DCs are also strongly correlated with Th-1 cells and immune cytotoxicity signals, and are positively associated with OS, because they can support TLSs to participate in promoting protective immunity in NSCLC. Another major subtype of follicular dendritic cells is discussed later.

3.4. High Endothelial Venules

Tumor-associated HEVs characterized by MECA-79 and peripheral node addressin (PNAd) are frequently found in TLSs and have been proposed to play important roles in lymphocyte entry into tumors, which is a process essential for successful antitumor immunity

[77][93]. In a murine model of colon carcinoma, HEVs were observed to control the formation of TLSs via production of IL-36γ

[78][94]. Numerous studies have shown that the density of HEVs is strongly correlated to the density of TLSs and is a positive predictor in many cancer types

[27][78][79][80][27,94,95,96].

3.5. TLS-Associated Immune Cells

Immune fibroblasts are considered necessary for the early phase of TLS formation via building a network whose expansion is mediated by IL-22 and lymphotoxin α1β2 (LTα1β2) to support TLSs

[81][82][97,98]. Some studies have shown that TLSs are not promoted by chronic inflammatory conditions in all organs because immune-associated fibroblasts are necessary and indispensable

[83][84][99,100]. In a mouse model of TLSs, the subcutaneous injection of immune fibroblasts successfully induced TLSs that attracted the infiltration of host immune-cell subsets

[17]. Follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) are a specialized type of DC and are detected in the germinal center via labeling CD21, serving as immune-associated fibroblasts

[85][101]. FDCs form a dense three-dimensional follicular network, which lays a foundation for the generation of TLSs. In addition to antigen presentation and providing structural support, FDCs are able to modulate B cell diversity and enhance B memory cell differentiation in GCs

[86][87][102,103]. The abundance of FDCs has been positively associated with the density of TLSs, suggesting better prognosis

[11].

Macrophages are characterized by the expression of CD68 and multiple functions. A previous study suggested that macrophages could secrete IL-36γ to control TLS formation

[78][94] and were responsible for recruiting CD4+ T cells and B cells to promote the formation of TLSs as antigen presentation cells

[88][104]. Additionally, macrophages are one of the main types of effector cells of ADCC and ADCP, which are primary anti-tumor mechanisms of humoral immunity in solid tumors. However, following ADCP, macrophages may up-regulate PD-L1 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase to support local immunosuppression

[89][105]. In addition, a previous study on soft tissue sarcomas showed that macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF1R) responses were more frequent in TLSs compared with tumor tissue without TLSs. CSF1R is a marker of immunosuppressive macrophages, which are believed to maintain an anti-inflammatory niche for malignant cell growth

[90][106].