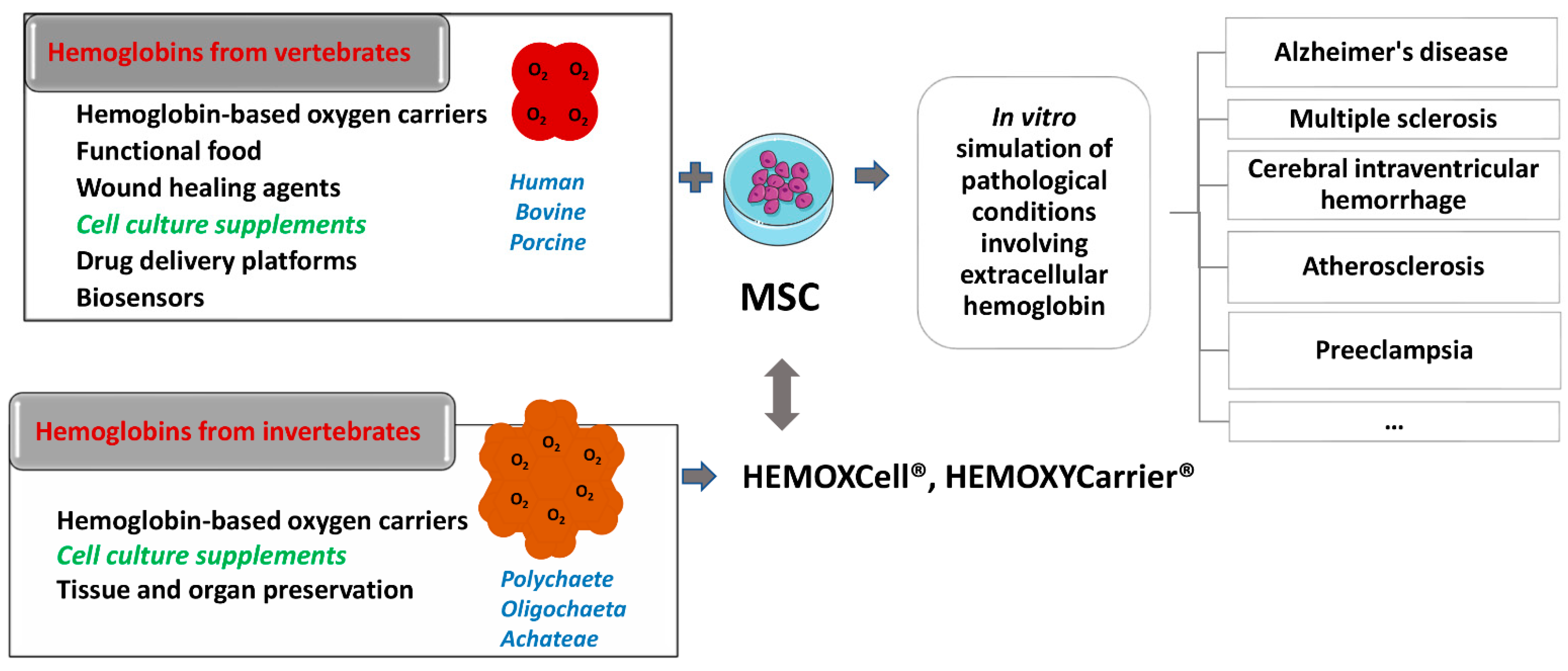

Hemoglobin is essential for maintaining cellular bioenergetic homeostasis through its ability to bind and transport oxygen to the tissues. Besides its ability to transport oxygen, hemoglobin within erythrocytes plays an important role in cellular signaling and modulation of the inflammatory response either directly by binding gas molecules (NO, CO, and CO2) or indirectly by acting as their source. Once hemoglobin reaches the extracellular environment, it acquires several secondary functions affecting surrounding cells and tissues. By modulating the cell functions, this macromolecule becomes involved in the etiology and pathophysiology of various diseases. The up-to-date results disclose the impact of extracellular hemoglobin on (i) redox status, (ii) inflammatory state of cells, (iii) proliferation and chemotaxis, (iv) mitochondrial dynamic, (v) chemoresistance and (vi) differentiation.

- extracellular hemoglobin

- oxygen carriers

- cell culture additives

1. Introduction

2. Extracellular Hemoglobin in Mammals

2.1. Endogeous Extracellular Hemoglobin Removal and Degradation

2.2. Endogenous Extracellular Hemoglobin Mode of Action

3. Exogenous Administration of Extracellular Hemoglobin

References

- Quaye, I.K. Extracellular Hemoglobin: The Case of a Friend Turned Foe. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 96.

- Coates, C.J.; Decker, H. Immunological Properties of Oxygen-Transport Proteins: Hemoglobin, Hemocyanin and Hemerythrin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 74, 293–317.

- Olson, J.S. Lessons Learned from 50 Years of Hemoglobin Research: Unstirred and Cell-Free Layers, Electrostatics, Baseball Gloves, and Molten Globules. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 228–246.

- Rifkind, J.M.; Mohanty, J.G.; Nagababu, E. The Pathophysiology of Extracellular Hemoglobin Associated with Enhanced Oxidative Reactions. Front. Physiol. 2015, 5, 500.

- Lara, F.A.; Kahn, S.A.; Da Fonseca, A.C.C.; Bahia, C.P.; Pinho, J.P.C.; Graca-Souza, A.V.; Houzel, J.C.; De Oliveira, P.L.; Moura-Neto, V.; Oliveira, M.F. On the fate of extracellular hemoglobin and heme in brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009, 29, 1109–1120.

- Rother, R.P.; Bell, L.; Hillmen, P. The clinical sequelae of Intravascular Hemolysis A Novel Mechanism of Human Disease. JAMA 2015, 293, 1653–1662.

- Ogasawara, N.; Oguro, T.; Sakabe, T.; Matsushima, M.; Takikawa, O.; Isobe, K.I.; Nagase, F. Hemoglobin Induces the Expression of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase in Dendritic Cells through the Activation of PI3K, PKC, and NF-ΚB and the Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 108, 716–725.

- Jeney, V.; Eaton, J.W.; Balla, G.; Balla, J. Natural History of the Bruise: Formation, Elimination, and Biological Effects of Oxidized Hemoglobin. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 703571.

- Bahl, N.; Winarsih, I.; Tucker-Kellogg, L.; Ding, J.L. Extracellular Haemoglobin Upregulates and Binds to Tissue Factor on Macrophages: Implications for Coagulation and Oxidative Stress. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 111, 67–78.

- Schaer, D.J.; Buehler, P.W.; Alayash, A.I.; Belcher, J.D.; Vercellotti, G.M. Hemolysis and Free Hemoglobin Revisited: Exploring Hemoglobin and Hemin Scavengers as a Novel Class of Therapeutic Proteins. Blood 2013, 121, 1276–1285.

- Jeney, V. Pro-Inflammatory Actions of Red Blood Cell-Derived DAMPs. In Inflammasomes: Clinical and Therapeutic Implications, Experientia Supplementum; Cordero, M., Alcocer-Gómez, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 108, pp. 211–233.

- Garton, T.; Keep, R.F.; Hua, Y.; Xi, G. CD163, a Hemoglobin/Haptoglobin Scavenger Receptor, After Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Functions in Microglia/Macrophages Versus Neurons. Transl. Stroke Res. 2017, 8, 612–616.

- Smith, A.; McCulloh, R.J. Hemopexin and Haptoglobin: Allies against Heme Toxicity from Hemoglobin Not Contenders. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 187.

- McCormick, D.J.; Atassi, M.Z. Hemoglobin Binding with Haptoglobin: Delineation of the Haptoglobin Binding Site on the α-Chain of Human Hemoglobin. J. Protein Chem. 1990, 9, 735–742.

- Kaempfer, T.; Duerst, E.; Gehrig, P.; Roschitzki, B.; Rutishauser, D.; Grossmann, J.; Schoedon, G.; Vallelian, F.; Schaer, D.J. Extracellular Hemoglobin Polarizes the Macrophage Proteome toward Hb-Clearance, Enhanced Antioxidant Capacity and Suppressed HLA Class 2 Expression. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 2397–2408.

- Smeds, E.; Romantsik, O.; Jungner, Å.; Erlandsson, L.; Gram, M. Pathophysiology of Extracellular Haemoglobin: Use of Animal Models to Translate Molecular Mechanisms into Clinical Significance. ISBT Sci. Ser. 2017, 12, 134–141.

- Belcher, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Abdulla, F.; Zhang, P.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen, P.; Killeen, T.; Miescher, S.M.; Brinkman, N.; et al. Haptoglobin and Hemopexin Inhibit Vaso-Occlusion and Inflammation in Murine Sickle Cell Disease: Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 Induction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196455.

- Lee, S.K.; Ding, J.L. A Perspective on the Role of Extracellular Hemoglobin on the Innate Immune System. DNA Cell Biol. 2013, 32, 36–40.

- Ponka, P.; Sheftel, A.D.; English, A.M.; Scott Bohle, D.; Garcia-Santos, D. Do Mammalian Cells Really Need to Export and Import Heme? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 395–406.

- Sverrisson, K.; Axelsson, J.; Rippe, A.; Gram, M.; Åkerström, B.; Hansson, S.R.; Rippe, B. Extracellular Fetal Hemoglobin Induces Increases in Glomerular Permeability: Inhibition with A1 -Microglobulin and Tempol. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2014, 306, 442–448.

- Penders, J.; Delanghe, J.R. Alpha 1-Microglobulin: Clinical Laboratory Aspects and Applications. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 346, 107–118.

- Olsson, M.; Olofsson, T.; Tapper, H.; Åkerström, B. The Lipocalin Aa1-Microglobulin Protects Erythroid K562 Cells against Oxidative Damage Induced by Heme and Reactive Oxygen Species. Free Radic. Res. 2008, 42, 725–736.

- Munoz, J.C.; Pires, S.I.; Baek, H.J.; Buehler, W.P.; Palmer, F.A.; Cabrales, P. Apohemoglobin-Haptoglobin Complex Attenuates the Pathobiology of Circulating Acellular 2 Hemoglobin and Heme. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1296–H1307.

- Subramanian, K.; Du, R.; Tan, N.S.; Ho, B.; Ding, J.L. CD163 and IgG Codefend against Cytotoxic Hemoglobin via Autocrine and Paracrine Mechanisms. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 5267–5278.

- Nakai, K.; Sakuma, I.; Ohta, T.; Ando, J.; Kitabatake, A.; Nakazato, Y.; Takahashi, T.A. Permeability Characteristics of Hemoglobin Derivatives across Cultured Endothelial Cell Monolayers. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1998, 132, 313–319.

- Matheson, B.; Razynska, A.; Kwansa, H.; Bucci, E. Appearance of Dissociable and Cross-Linked Hemoglobins in the Renal Hilar Lymph. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2000, 135, 459–464.

- Schechter, A.N. Hemoglobin Research and the Origins of Molecular Medicine. Blood 2008, 112, 3927–3938.

- Akira, S.; Hemmi, H. Recognition of Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns by TLR Family. Immunol. Lett. 2003, 85, 85–95.

- Bozza, M.T.; Jeney, V. Pro-inflammatory Actions of Heme and Other Hemoglobin-Derived DAMPs. Front. Immunol. 2020, 30, 1323.

- Helms, C.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B. Hemoglobin-Mediated Nitric Oxide Signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 464–472.

- Alayash, A.I. Oxygen therapeutics: Can we tame haemoglobin? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 152–159.

- Doherty, D.H.; Doyle, M.P.; Curry, S.R.; Vali, R.J.; Fattor, T.J.; Olson, J.S.; Lemon, D.D. Rate of reaction with nitric oxide determines the hypertensive effect of cell-free hemoglobin. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 672–676.

- Reeder, B.J. The Redox Activity of Hemoglobins: From Physiologic Functions to Pathologic Mechanisms. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 1087–1123.

- Bamm, V.V.; Henein, M.E.L.; Sproul, S.L.J.; Lanthier, D.K.; Harauz, G. Potential Role of Ferric Hemoglobin in MS Pathogenesis: Effects of Oxidative Stress and Extracellular Methemoglobin or Its Degradation Products on Myelin Components. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 112, 494–503.

- Chintagari, N.R.; Jana, S.; Alayash, A.I. Oxidized Ferric and Ferryl Forms of Hemoglobin Trigger Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Injury in Alveolar Type i Cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 55, 288–298.

- Buehler, P.W.; D’Agnillo, F.; Hoffman, V.; Alayash, A.I. Effects of Endogenous Ascorbate on Oxidation, Oxygenation, and Toxicokinetics of Cell-Free Modified Hemoglobin after Exchange Transfusion in Rat and Guinea Pig. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007, 323, 49–60.

- Balla, G.; Jacob, H.S.; Eaton, J.W.; Belcher, J.D.; Vercellotti, G.M. Hemin: A Possible Physiological Mediator of Low Density Lipoprotein Oxidation and Endothelial Injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1991, 11, 1700–1711.

- Nagy, E.; Eaton, J.W.; Jeney, V.; Soares, M.P.; Varga, Z.; Galajda, Z.; Szentmiklósi, J.; Méhes, G.; Csonka, T.; Smith, A.; et al. Red Cells, Hemoglobin, Heme, Iron, and Atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1347–1353.

- Ogawa, K.; Sun, J.; Taketani, S.; Nakajima, O.; Nishitani, C.; Sassa, S.; Hayashi, N.; Yamamoto, M.; Shibahara, S.; Fujita, H.; et al. Heme Mediates Derepression of Maf Recognition Element through Direct Binding to Transcription Repressor Bach1. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 2835–2843.

- Raghuram, S.; Stayrook, K.R.; Huang, P.; Rogers, P.M.; Nosie, A.K.; McClure, D.B.; Burris, L.L.; Khorasanizadeh, S.; Burris, T.P.; Rastinejad, F. Identification of Heme as the Ligand for the Orphan Nuclear Receptors REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 1207–1213.

- Alayash, A.I. Hemoglobin-Based Blood Substitutes: Oxygen Carriers, Pressor Agents, or Oxidants? Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 545–549.

- Bialas, C.; Moser, C.; Sims, C.A. Artificial Oxygen Carriers and Red Blood Cell Substitutes: A Historic Overview and Recent Developments toward Military and Clinical Relevance. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 87 (Suppl. S1), S48–S58.

- Baron, J.F. Blood substitutes. Haemoglobin therapeutics in clinical practice. Crit. Care 1999, 3, R99–R102.

- Amberson, W.R. Clinical experience with hemoglobin-saline solutions. Science 1947, 106, 117.

- Savitsky, J.P.; Doczi, J.; Black, J.; Arnold, J.D. A clinical safety trial of stroma-free hemoglobin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1978, 23, 73–80.

- Bunn, H.F.; Esham, W.T.; Bull, R.W. The renal handling of hemoglobin. I. Glomerular filtration. J. Exp. Med. 1969, 129, 909–923.

- Sen Gupta, A. Hemoglobin-based Oxygen Carriers: Current State-of-the-art and Novel Molecules. Shock 2019, 52 (Suppl. S1), 70–83.

- Sakai, H.; Sou, K.; Horinouchi, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Tsuchida, E. Review of hemoglobin-vesicles as artificial oxygen carriers. Artif. Organs 2009, 33, 139–145.

- Hoffman, S.J.; Looker, D.L.; Roehrich, J.M.; Cozart, P.E.; Durfee, S.L.; Tedesco, J.L.; Stetler, G.L. Expression of fully functional tetrameric human hemoglobin in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 8521–8525.

- Resta, T.C.; Walker, B.R.; Eichinger, M.R.; Doyle, M.P. Rate of NO scavenging alters effects of recombinant hemoglobin solutions on pulmonary vasoreactivity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 1327–1336.

- Varnado, C.L.; Mollan, T.L.; Birukou, I.; Smith, B.J.; Henderson, D.P.; Olson, J.S. Development of recombinant hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2314–2328.

- Chen, J.Y.; Scerbo, M.; Kramer, G. A Review of Blood Substitutes: Examining the History, Clinical Trial Results, and Ethics of Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers. Clinics 2009, 64, 803–813.

- Lamy, M.L.; Daily, E.K.; Brichant, J.F.; Larbuisson, R.P.; Demeyere, R.H.; Vandermeersch, E.A.; Lehot, J.J.; Parsloe, M.R.; Berridge, J.C.; Sinclair, C.J.; et al. Randomized Trial of Diaspirin Cross-Linked Hemoglobin Solution as an Alternative to Blood Transfusion after Cardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2000, 92, 646–656.

- Winslow, R.M. New transfusion strategies: Red Cell Substitutes. Annu. Rev. Med. 1999, 50, 337–353.

- Jahr, S.J.; Moallempour, M.; Lim, C.J. HBOC-201, Hemoglobin Glutamer-250 (Bovine), Hemopure (Biopure Corporation). Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008, 8, 1425–1433.

- Gould, S.A.; Moore, E.E.; Hoyt, D.B.; Burch, J.M.; Haenel, J.B.; Garcia, J.; DeWoskin, R.; Moss, G.S. The First Randomized Trial of Human Polymerized Hemoglobin as a Blood Substitute in Acute Trauma and Emergent Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1998, 187, 113–120.

- Cheng, D.C.H.; Mazer, C.D.; Martineau, R.; Ralph-Edwards, A.; Karski, J.; Robblee, J.; Finegan, B.; Hall, R.I.; Latimer, R.; Vuylsteke, A. A Phase II Dose-Response Study of Hemoglobin Raffimer (Hemolink) in Elective Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2004, 127, 79–86.

- Olofsson, C.; Ahl, T.; Johansson, T.; Larsson, S.; Nellgård, P.; Ponzer, S.; Fagrell, B.; Przybelski, R.; Keipert, P.; Winslow, N.; et al. A Multicenter Clinical Study of the Safety and Activity of Maleimide-Polyethylene Glycol-Modified Hemoglobin (Hemospan®) in Patients Undergoing Major Orthopedic Surgery. Anesthesiology 2006, 105, 1153–1163.

- Abuchowski, A. SANGUINATE (PEGylated Carboxyhemoglobin Bovine): Mechanism of Action and Clinical Update. Artif. Organs 2017, 41, 346–350.

- Tomita, D.; Kimura, T.; Hosaka, H.; Daijima, Y.; Haruki, R.; Ludwig, K.; Böttcher, C.; Komatsu, T. Covalent Core-Shell Architecture of Hemoglobin and Human Serum Albumin as an Artificial O2 Carrier. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1816–1825.

- Iwasaki, H.; Yokomaku, K.; Kureishi, M.; Igarashi, K.; Hashimoto, R.; Kohno, M.; Iwazaki, M.; Haruki, R.; Akiyama, M.; Asai, K.; et al. Hemoglobin–Albumin Cluster: Physiological Responses after Exchange Transfusion into Rats and Blood Circulation Persistence in Dogs. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46 (Suppl. 3), S621–S629.

- Chang, T.M. Semipermeable microcapsules. Science 1964, 146, 524–525.

- Bugarski, B.; Dovezenski, N.; Stojanovic, N.; Bugarski, D.; Koncern, H. Emulsion Containing Hydrophobic Nanodrops with Bound Hemoglobin Molecules in a Hydrophilic Phase as a Blood Substitute. Deutsches Patentamt DE 2002-10209860 WO 2003074022, 9 December 2003.

- Banerjee, U.; Wolfe, S.; O’Boyle, Q.; Cuddington, C.; Palmer, A.F. Scalable production and complete biophysical characterization of poly(ethylene glycol) surface conjugated liposome encapsulated hemoglobin (PEG-LEH). PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269939.

- Azuma, H.; Amano, T.; Kamiyama, N.; Takehara, N.; Jingu, M.; Takagi, H.; Sugita, O.; Kobayashi, N.; Kure, T.; Shimizu, T.; et al. First-in-human phase 1 trial of hemoglobin vesicles as artificial red blood cells developed for use as a transfusion alternative. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 5711–5715.

- Arenberger, P.; Engels, P.; Arenbergerova, M.; Gkalpakiotis, S.; García Luna Martínez, F.J.; Villarreal Anaya, A.; Jimenez Fernandez, L. Clinical Results of the Application of a Hemoglobin Spray to Promote Healing of Chronic Wounds. GMS Krankenhhyg. Interdiszip. 2011, 6, Doc05.

- Elg, F.; Hunt, S. Hemoglobin Spray as Adjunct Therapy in Complex Wounds: Meta-Analysis versus Standard Care Alone in Pooled Data by Wound Type across Three Retrospective Cohort Controlled Evaluations. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 205031211878431.

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Jin, Q.; Ji, J. Hemoglobin as a Smart PH-Sensitive Nanocarrier to Achieve Aggregation Enhanced Tumor Retention. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 2007–2013.

- Qi, W.; Yan, X.; Duan, L.; Cui, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Glucose-Sensitive Microcapsules from Glutaraldehyde Cross-Linked Hemoglobin and Glucose Oxidase. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1212–1216.

- Stančić, A.Z.; Drvenica, I.T.; Obradović, H.N.; Bugarski, B.M.; Lj Ilić, V.; Bugarski, D.S. Native Bovine Hemoglobin Reduces Differentiation Capacity of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 909–920.

- Dutheil, D.; Rousselot, M.; Hauet, T.; Zal, F. Organ-Preserving Composition and Uses. U.S. Patent US 2014/0113274 A1, 24 April 2014. Available online: http://www.freepatentsonline.com/y2014/0113274.html (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Schweitzer, M.H.; Zheng, W.; Cleland, T.P.; Goodwin, M.B.; Boatman, E.; Theil, E.; Marcus, M.A.; Fakra, S.C. A role for iron and oxygen chemistry in preserving soft tissues, cells and molecules from deep time. Proc. Biol. Sci. B 2013, 281, 20132741.

- Le Pape, F.; Cosnuau-Kemmat, L.; Gaëlle, R.; Dubrana, F.; Férec, C.; Zal, F.; Leize, E.; Delépine, P. HEMOXCell, a New Oxygen Carrier Usable as an Additive for Mesenchymal Stem Cell Culture in Platelet Lysate-Supplemented Media. Artif. Organs 2017, 41, 359–371.

- Magaldi, A.G.; Ghiretti, F.; Tognon, G.; Zanotti, G. The Structure of the Extracellular Hemoglobin of Annelids. In Invertebrate Oxygen Carriers; Linzen, B., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986.

- Zal, F.; Rousselot, M. Extracellular Hemoglobins from Annelids, and Their Potential Use in Biotechnology. In Outstanding Marine Molecules: Chemistry, Biology, Analysis; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 361–376.

- Batool, F.; Delpy, E.; Zal, F.; Leize-Zal, E.; Huck, O. Therapeutic Potential of Hemoglobin Derived from the Marine Worm Arenicola Marina (M101): A Literature Review of a Breakthrough Innovation. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 376.

- Zal, F.; Green, B.N.; Lallier, F.H.; Vinogradov, S.N.; Toulmond, A. Quaternary Structure of the Extracellular Haemoglobin of the Lugworm Arenicola Marina. A Multi-Angle-Laser-Light-Scattering and Electrospray-Ionisation-Mass-Spectrometry Analysis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 243, 85–92.

- Rousselot, M.; Delpy, E.; La Rochelle, C.D.; Lagente, V.; Pirow, R.; Rees, J.F.; Hagege, A.; Le Guen, D.; Hourdez, S.; Zal, F. Arenicola Marina Extracellular Hemoglobin: A New Promising Blood Substitute. Biotechnol. J. 2006, 1, 333–345.

- Elmer, J.; Palmer, A.F. Biophysical Properties of Lumbricus terrestris Erythrocruorin and Its Potential Use as a Red Blood Cell Substitute. J. Funct. Biomater. 2012, 3, 49–60.