While the Michael addition has been employed for more than 130 years for the synthesis of a vast diversity of compounds, the reversibility of this reaction when heteronucleophiles are involved has been generally less considered. First applied to medicinal chemistry, the reversible character of the hetero-Michael reactions has recently been explored for the synthesis of Covalent Adaptable Networks (CANs), in particular the thia-Michael reaction and more recently the aza-Michael reaction. In these cross-linked networks, exchange reactions take place between two Michael adducts by successive dissociation and association steps. In order to understand and precisely control the exchange in these CANs, it is necessary to get an insight into the critical parameters influencing the Michael addition and the dissociation rates of Michael adducts by reconsidering previous studies on these matters.

- Michael

- vitrimers

- covalent adaptable network

- thia-Michael

1. Introduction

2. Thia-Michael Reaction

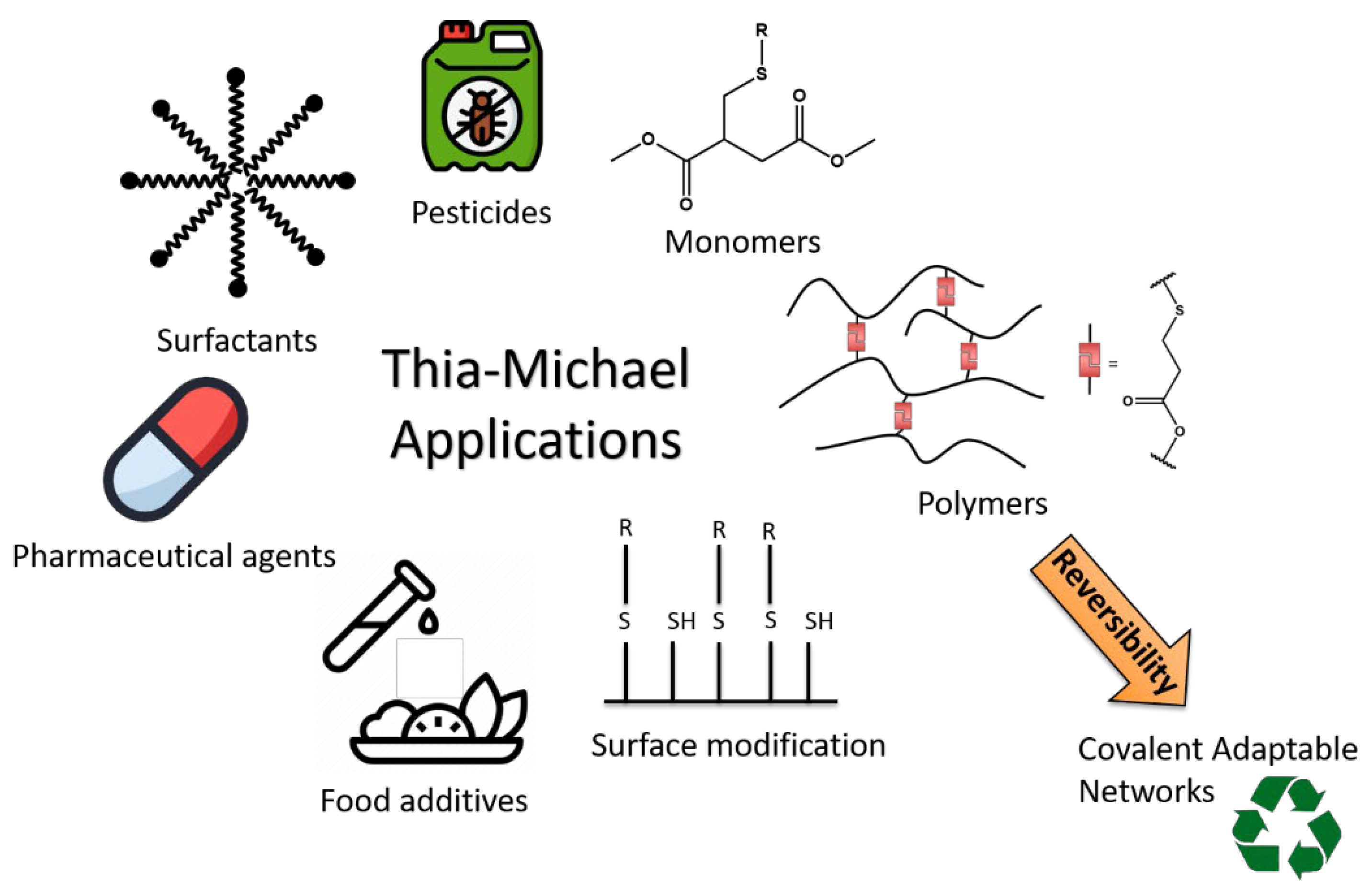

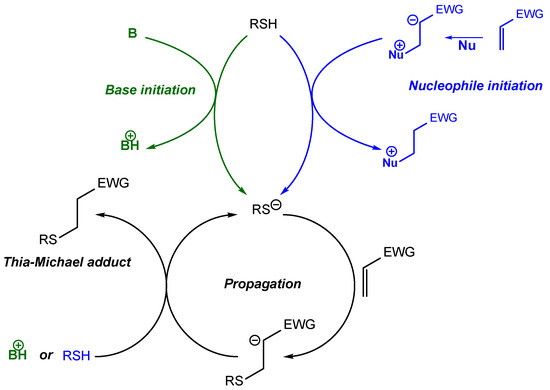

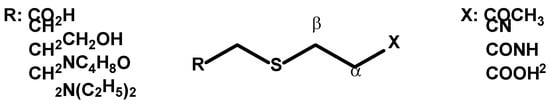

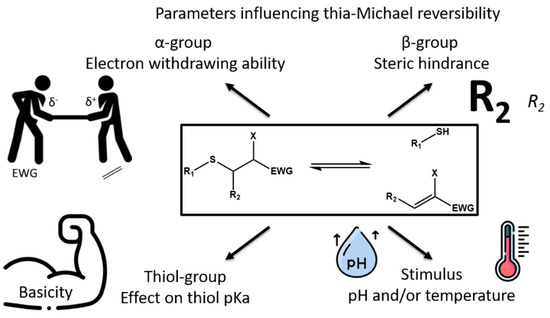

The thia-Michael addition is an intensively used reaction in industry for the synthesis of food additives and surfactants, pesticides and pharmaceutical agents [34,35,36,37,38][29][30][31][32][33]. In recent decades, the thia-Michael addition has found a new field of application in materials science. Indeed, the simplicity of this addition reaction enables to easily synthesize a large range of monomers [39][34] or dendrimers [40][35] and can also be used to perform surface modification [41][36]. Polymer networks synthesized via thia-Michael addition have been also explored. For instance, thio-acrylate networks were prepared by using a thia-Michael addition followed by the photopolymerization of an excess of acrylate functional groups [42][37]. Using a similar idea, A. Lowe et al. performed sequential phosphine-catalyzed thia-Michael addition followed by radical-mediated thiol−yne reaction to prepare polyfunctional materials [43][38]. The thia-Michael addition has also been used to cross-link acrylated epoxidized soybean oil in order to obtain partially bio-based networks [44][39]. Recently, some dynamic covalent networks (CANs) have been designed on the basis of the reversibility of the thia-Michael addition (Scheme 1) [45,46][40][41]. For the following discussion, the term “thia-Michael addition” refers only to the addition step, whereas the term “thia-Michael equilibrium” refers to the overall thia-Michael reaction (elimination/addition). Finally, the term “thia-Michael exchange” refers to the reaction between a Michael adduct and a Michael donor or acceptor. The thia-Michael exchange, which is focused on in this entreviewy, is of course dependent on a few critical parameters such as the promotor or catalyst, the solvent and the structure of the reagents (thiol and Michael acceptor).

3. Thia-Michael Equilibrium and Exchange Kinetics

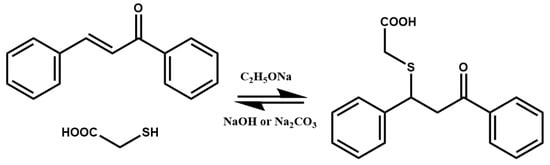

The reversible character of the thia-Michael addition was evidenced for the first time in 1931 by B. Nicolet [65][60] who demonstrated the reversibility of the addition of thioglycolic acid on benzalacetophenone (Scheme 3). The thia-Michael adducts dissociated when placed in a basic medium composed of sodium hydroxide or sodium carbonate.

References

- Fotouhi, L.; Heravi, M.M.; Zadsirjan, V.; Atoi, P.A. Electrochemically Induced Michael Addition Reaction: An Overview. Chem. Rec. 2018, 18, 1633–1657.

- Michael, A. On the Addition of Sodium Acetacetic Ether and Analogous Sodium Compounds to Unsaturated Organic Ethers. Am. Chem. J. 1887, 9, 112.

- Mather, B.D.; Viswanathan, K.; Miller, K.M.; Long, T.E. Michael Addition Reactions in Macromolecular Design for Emerging Technologies. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 487–531.

- Patrick, J.F.; Robb, M.J.; Sottos, N.R.; Moore, J.S.; White, S.R. Polymers with Autonomous Life-Cycle Control. Nature 2016, 540, 363–370.

- Zheng, N.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. Dynamic Covalent Polymer Networks: A Molecular Platform for Designing Functions beyond Chemical Recycling and Self-Healing. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 1716–1745.

- Tobolsky, A.V.; Prettyman, I.B.; Dillon, J.H. Stress Relaxation of Natural and Synthetic Rubber Stocks. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1944, 17, 551–575.

- Stern, M.D.; Tobolsky, A.V. Stress-Time-Temperature Relations in Polysulfide Rubbers. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1946, 19, 1178–1192.

- Zheng, P.; McCarthy, T.J. A Surprise from 1954: Siloxane Equilibration Is a Simple, Robust, and Obvious Polymer Self-Healing Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2024–2027.

- Osthoff, R.C.; Bueche, A.M.; Grubb, W.T. Chemical Stress-Relaxation of Polydimethylsiloxane Elastomers 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 4659–4663.

- Lyon, G.B.; Baranek, A.; Bowman, C.N. Scaffolded Thermally Remendable Hybrid Polymer Networks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1477–1485.

- Reutenauer, P.; Buhler, E.; Boul, P.J.; Candau, S.J.; Lehn, J.-M. Room Temperature Dynamic Polymers Based on Diels-Alder Chemistry. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2009, 15, 1893–1900.

- Chen, X.; Dam, M.A.; Ono, K.; Mal, A.; Shen, H.; Nutt, S.R.; Sheran, K.; Wudl, F. A Thermally Re-Mendable Cross-Linked Polymeric Material. Science 2002, 295, 1698–1702.

- Zhang, B.; Digby, Z.A.; Flum, J.A.; Foster, E.M.; Sparks, J.L.; Konkolewicz, D. Self-Healing, Malleable and Creep Limiting Materials Using Both Supramolecular and Reversible Covalent Linkages. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 7368–7372.

- Montarnal, D.; Capelot, M.; Tournilhac, F.; Leibler, L. Silica-Like Malleable Materials from Permanent Organic Networks. Science 2011, 334, 965–968.

- Han, J.; Liu, T.; Hao, C.; Zhang, S.; Guo, B.; Zhang, J. A Catalyst-Free Epoxy Vitrimer System Based on Multifunctional Hyperbranched Polymer. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 6789–6799.

- Altuna, F.I.; Hoppe, C.E.; Williams, R.J.J. Shape Memory Epoxy Vitrimers Based on DGEBA Crosslinked with Dicarboxylic Acids and Their Blends with Citric Acid. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 88647–88655.

- Altuna, F.I.; Casado, U.; Dell’Erba, I.E.; Luna, L.; Hoppe, C.E.; Williams, R.J.J. Epoxy Vitrimers Incorporating Physical Crosslinks Produced by Self-Association of Alkyl Chains-SI. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 1337–1347.

- Chen, X.; Li, L.; Jin, K.; Torkelson, J.M. Reprocessable Polyhydroxyurethane Networks Exhibiting Full Property Recovery and Concurrent Associative and Dissociative Dynamic Chemistry: Via Transcarbamoylation and Reversible Cyclic Carbonate Aminolysis. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 6349–6355.

- Fortman, D.J.; Brutman, J.P.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Dichtel, W.R. Structural Effects on the Reprocessability and Stress Relaxation of Crosslinked Polyhydroxyurethanes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44984.

- Fortman, D.J.; Brutman, J.P.; Cramer, C.J.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Dichtel, W.R. Mechanically Activated, Catalyst-Free Polyhydroxyurethane Vitrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 14019–14022.

- Elizalde, F.; Aguirresarobe, R.H.; Gonzalez, A.; Sardon, H. Dynamic Polyurethane Thermosets: Tuning Associative/Dissociative Behavior by Catalyst Selection. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 5386–5396.

- Van Lijsebetten, F.; Spiesschaert, Y.; Winne, J.M.; Du Prez, F.E. Reprocessing of Covalent Adaptable Polyamide Networks through Internal Catalysis and Ring-Size Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 15834–15844.

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Majumdar, S.; van Benthem, R.A.T.M.; Heuts, J.P.A.; Sijbesma, R.P. Dynamic Polyamide Networks via Amide–Imide Exchange. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 9703–9711.

- Denissen, W.; Winne, J.M.; Du Prez, F.E. Vitrimers: Permanent Organic Networks with Glass-like Fluidity. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 30–38.

- Elling, B.R.; Dichtel, W.R. Reprocessable Cross-Linked Polymer Networks: Are Associative Exchange Mechanisms Desirable? ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1488–1496.

- Zhang, L.; Rowan, S.J. Effect of Sterics and Degree of Cross-Linking on the Mechanical Properties of Dynamic Poly(Alkylurea–Urethane) Networks. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 5051–5060.

- Hayashi, M.; Chen, L. Functionalization of Triblock Copolymer Elastomers by Cross-Linking the End Blocks via Trans-N -Alkylation-Based Exchangeable Bonds. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 1713–1719.

- Jourdain, A.; Asbai, R.; Anaya, O.; Chehimi, M.M.; Drockenmuller, E.; Montarnal, D. Rheological Properties of Covalent Adaptable Networks with 1,2,3-Triazolium Cross-Links: The Missing Link between Vitrimers and Dissociative Networks. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1884–1900.

- Liu, G.; Link, J.T.; Pei, Z.; Reilly, E.B.; Leitza, S.; Nguyen, B.; Marsh, K.C.; Okasinski, G.F.; Von Geldern, T.W.; Ormes, M.; et al. Discovery of Novel P-Arylthio Cinnamides as Antagonists of Leukocyte Function-Associated Antigen-1/Intracellular Adhesion Molecule-1 Interaction. 1. Identification of an Additional Binding Pocket Based on an Anilino Diaryl Sulfide Lead. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 4025–4040.

- Yang, D.J.; Chen, B. Simultaneous Determination of Nonnutritive Sweeteners in Foods by HPLC/ESI-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3022–3027.

- Matsuno, R.; Takami, K.; Ishihara, K. Simple Synthesis of a Library of Zwitterionic Surfactants via Michael-Type Addition of Methacrylate and Alkane Thiol Compounds. Langmuir 2010, 26, 13028–13032.

- Alswieleh, A.M.; Cheng, N.; Canton, I.; Ustbas, B.; Xue, X.; Ladmiral, V.; Xia, S.; Ducker, R.E.; El Zubir, O.; Cartron, M.L.; et al. Zwitterionic Poly(Amino Acid Methacrylate) Brushes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9404–9413.

- Dunbar, K.L.; Scharf, D.H.; Litomska, A.; Hertweck, C. Enzymatic Carbon–Sulfur Bond Formation in Natural Product Biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 5521–5577.

- Giacobazzi, G.; Gioia, C.; Colonna, M.; Celli, A. Thia-Michael Reaction for a Thermostable Itaconic-Based Monomer and the Synthesis of Functionalized Biopolyesters. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5553–5559.

- Chatani, S.; Podgórski, M.; Wang, C.; Bowman, C.N. Facile and Efficient Synthesis of Dendrimers and One-Pot Preparation of Dendritic-Linear Polymer Conjugates via a Single Chemistry: Utilization of Kinetically Selective Thiol-Michael Addition Reactions. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 4894–4900.

- Khire, V.S.; Lee, T.Y.; Bowman, C.N. Surface Modification Using Thiol−Acrylate Conjugate Addition Reactions. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 5669–5677.

- Chan, J.W.; Wei, H.; Zhou, H.; Hoyle, C.E. The Effects of Primary Amine Catalyzed Thio-Acrylate Michael Reaction on the Kinetics, Mechanical and Physical Properties of Thio-Acrylate Networks. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 2717–2725.

- Chan, J.W.; Hoyle, C.E.; Lowe, A.B. Sequential Phosphine-Catalyzed, Nucleophilic Thiol−Ene/Radical-Mediated Thiol−Yne Reactions and the Facile Orthogonal Synthesis of Polyfunctional Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 5751–5753.

- Kasetaite, S.; De la Flor, S.; Serra, A.; Ostrauskaite, J. Effect of Selected Thiols on Cross-Linking of Acrylated Epoxidized Soybean Oil and Properties of Resulting Polymers. Polymers 2018, 10, 439.

- Zhang, B.; Digby, Z.A.; Flum, J.A.; Chakma, P.; Saul, J.M.; Sparks, J.L.; Konkolewicz, D. Dynamic Thiol–Michael Chemistry for Thermoresponsive Rehealable and Malleable Networks. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6871–6878.

- Chakma, P.; Rodrigues Possarle, L.H.; Digby, Z.A.; Zhang, B.; Sparks, J.L.; Konkolewicz, D. Dual Stimuli Responsive Self-Healing and Malleable Materials Based on Dynamic Thiol-Michael Chemistry. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 6534–6543.

- Li, G.Z.; Randev, R.K.; Soeriyadi, A.H.; Rees, G.; Boyer, C.; Tong, Z.; Davis, T.P.; Becer, C.R.; Haddleton, D.M. Investigation into Thiol-(Meth)Acrylate Michael Addition Reactions Using Amine and Phosphine Catalysts. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 1196–1204.

- Nair, D.P.; Podgórski, M.; Chatani, S.; Gong, T.; Xi, W.; Fenoli, C.R.; Bowman, C.N. The Thiol-Michael Addition Click Reaction: A Powerful and Widely Used Tool in Materials Chemistry. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 724–744.

- Chatani, S.; Nair, D.P.; Bowman, C.N. Relative Reactivity and Selectivity of Vinyl Sulfones and Acrylates towards the Thiol–Michael Addition Reaction and Polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 1048–1055.

- Chan, J.W.; Hoyle, C.E.; Lowe, A.B.; Bowman, M. Nucleophile-Initiated Thiol-Michael Reactions: Effect of Organocatalyst, Thiol, and Ene. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6381–6388.

- Kilambi, H.; Stansbury, J.W.; Bowman, C.N. Enhanced Reactivity of Monovinyl Acrylates Characterized by Secondary Functionalities toward Photopolymerization and Michael Addition: Contribution of Intramolecular Effects. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 3452–3458.

- Nguyen, L.-T.T.; Gokmen, M.T.; Prez, F.E. Du Kinetic Comparison of 13 Homogeneous Thiol–X Reactions. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 5527–5536.

- Lowe, A.B. Thiol-Ene “Click” Reactions and Recent Applications in Polymer and Materials Synthesis. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 17–36.

- Rizzi, S.C.; Hubbell, J.A. Recombinant Protein-Co-PEG Networks as Cell-Adhesive and Proteolytically Degradable Hydrogel Matrixes. Part I: Development and Physicochemical Characteristics. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1226–1238.

- Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; He, C.; Chung, T.; Goh, S. Effects of Chemistries of Trifunctional Amines on Mechanisms of Michael Addition Polymerizations with Diacrylates. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 6763–6770.

- Connor, R.; McClellan, W.R. The Michael Condensation. V. The Influence of the Experimental Conditions and the Structure of the Acceptor upon the Condensation. J. Org. Chem. 1939, 3, 570–577.

- Long, K.F.; Wang, H.; Dimos, T.T.; Bowman, C.N. Effects of Thiol Substitution on the Kinetics and Efficiency of Thiol-Michael Reactions and Polymerizations. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 3093–3100.

- Huang, S.; Kim, K.; Musgrave, G.M.; Sharp, M.; Sinha, J.; Stansbury, J.W.; Musgrave, C.B.; Bowman, C.N. Determining Michael Acceptor Reactivity from Kinetic, Mechanistic, and Computational Analysis for the Base-Catalyzed Thiol-Michael Reaction. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 3619–3628.

- Long, K.F.; Bongiardina, N.J.; Mayordomo, P.; Olin, M.J.; Ortega, A.D.; Bowman, C.N. Effects of 1°, 2°, and 3° Thiols on Thiol–Ene Reactions: Polymerization Kinetics and Mechanical Behavior. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 5805–5815.

- Gennari, A.; Wedgwood, J.; Lallana, E.; Francini, N.; Tirelli, N. Thiol-Based Michael-Type Addition. A Systematic Evaluation of Its Controlling Factors. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131637.

- Kade, M.J.; Burke, D.J.; Hawker, C.J. The Power of Thiol-Ene Chemistry. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 743–750.

- Koo, S.P.S.; Stamenović, M.M.; Prasath, R.A.; Inglis, A.J.; Du Prez, F.E.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Van Camp, W.; Junker, T. Limitations of Radical Thiol-Ene Reactions for Polymer–Polymer Conjugation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 1699–1713.

- Derboven, P.; D’hooge, D.R.; Stamenovic, M.M.; Espeel, P.; Marin, G.B.; Du Prez, F.E.; Reyniers, M.-F. Kinetic Modeling of Radical Thiol–Ene Chemistry for Macromolecular Design: Importance of Side Reactions and Diffusional Limitations. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1732–1742.

- Wadhwa, P.; Kharbanda, A.; Sharma, A. Thia-Michael Addition: An Emerging Strategy in Organic Synthesis. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018, 7, 634–661.

- Nicolet, B.H. The Mechanism of Sulfur Lability in Cysteine and Its Derivatives. I. Some Thio Ethers Readily Split by Alkali. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1931, 53, 3066–3072.

- Allen, C.F.H.; Humphlett, W.J. The Thermal Reversibility of the Michael Reaction: V. the Effect of the Structure of Certain Thiol Adducts on Cleavage. Can. J. Chem. 1966, 44, 2315–2321.

- Allen, C.F.H.; Fournier, J.O.; Humphlett, W.J. The Thermal Reversibility of the Michael Reaction: IV. Thiol Adducts. Can. J. Chem. 1964, 42, 2616–2620.

- Pritchard, R.B.; Lough, C.E.; Currie, D.J.; Holmes, H.L. Equilibrium Reactions of n -Butanethiol with Some Conjugated Heteroenoid Compounds. Can. J. Chem. 1968, 46, 775–781.

- Fishbein, J.C.; Jencks, W.P. Elimination Reactions of β-Cyano Thioethers: Evidence for a Carbanion Intermediate and a Change in Rate-Limiting Step. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 5075–5086.

- Serafimova, I.M.; Pufall, M.A.; Krishnan, S.; Duda, K.; Cohen, M.S.; Maglathlin, R.L.; McFarland, J.M.; Miller, R.M.; Frödin, M.; Taunton, J. Reversible Targeting of Noncatalytic Cysteines with Chemically Tuned Electrophiles. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 471–476.

- Jackson, P.A.; Widen, J.C.; Harki, D.A.; Brummond, K.M. Covalent Modifiers: A Chemical Perspective on the Reactivity of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyls with Thiols via Hetero-Michael Addition Reactions. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 839–885.

- Krishnan, S.; Miller, R.M.; Tian, B.; Mullins, R.D.; Jacobson, M.P.; Taunton, J. Design of Reversible, Cysteine-Targeted Michael Acceptors Guided by Kinetic and Computational Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12624–12630.

- Krenske, E.H.; Petter, R.C.; Houk, K.N. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Reversible Thiol Additions to Mono- and Diactivated Michael Acceptors: Implications for the Design of Drugs That Bind Covalently to Cysteines. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 11726–11733.

- Herbert, K.M.; Getty, P.T.; Dolinski, N.D.; Hertzog, J.E.; de Jong, D.; Lettow, J.H.; Romulus, J.; Onorato, J.W.; Foster, E.M.; Rowan, S.J. Dynamic Reaction-Induced Phase Separation in Tunable, Adaptive Covalent Networks. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 5028–5036.

- Schmidt, T.J.; Lyß, G.; Pahl, H.L.; Merfort, I. Helenanolide Type Sesquiterpene Lactones. Part 5: The Role of Glutathione Addition under Physiological Conditions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 2849–2855.

- Shi, B.; Greaney, M.F. Reversible Michael Addition of Thiols as a New Tool for Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2005, 7, 886.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xie, Y.; Greenberg, M.M.; Xi, Z.; Zhou, C. Thiol Specific and Tracelessly Removable Bioconjugation via Michael Addition to 5-Methylene Pyrrolones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6146–6151.