In the past, tThe Lorenz 1963 and 1969 models have been applied for revealing the chaotic nature of weather and climate and for estimating the atmospheric predictability limit. Recently, an in-depth analysis of classical Lorenz models (LMs) and newly developed, generalized Lorenz models suggested a revised view that “The atmosphere possesses chaos and order; it includes, as examples, emerging organized systems (such as tornadoes) and time varying forcing from recurrent seasons”, in contrast to the conventional view of “weather is chaotic”. The revised view focuses on distinct predictability and time varying multistability. Distinct predictability suggests limited predictability for chaotic solutions and unlimited predictability (or up to their lifetime) for non-chaotic solutions. To support the revised view, multistability (for attractor coexistence) and monostability (for single-type solutions) are first illustrated using kayaking and skiing as an analogy. Additionally, this entry provides a list of non-chaotic weather systems and a short list of suggested future tasks.

- dual nature

- chaos

- generalized Lorenz model

- predictability

- multistability

1. An Analogy for Monostability and Multistability Using Skiing and Kayaking

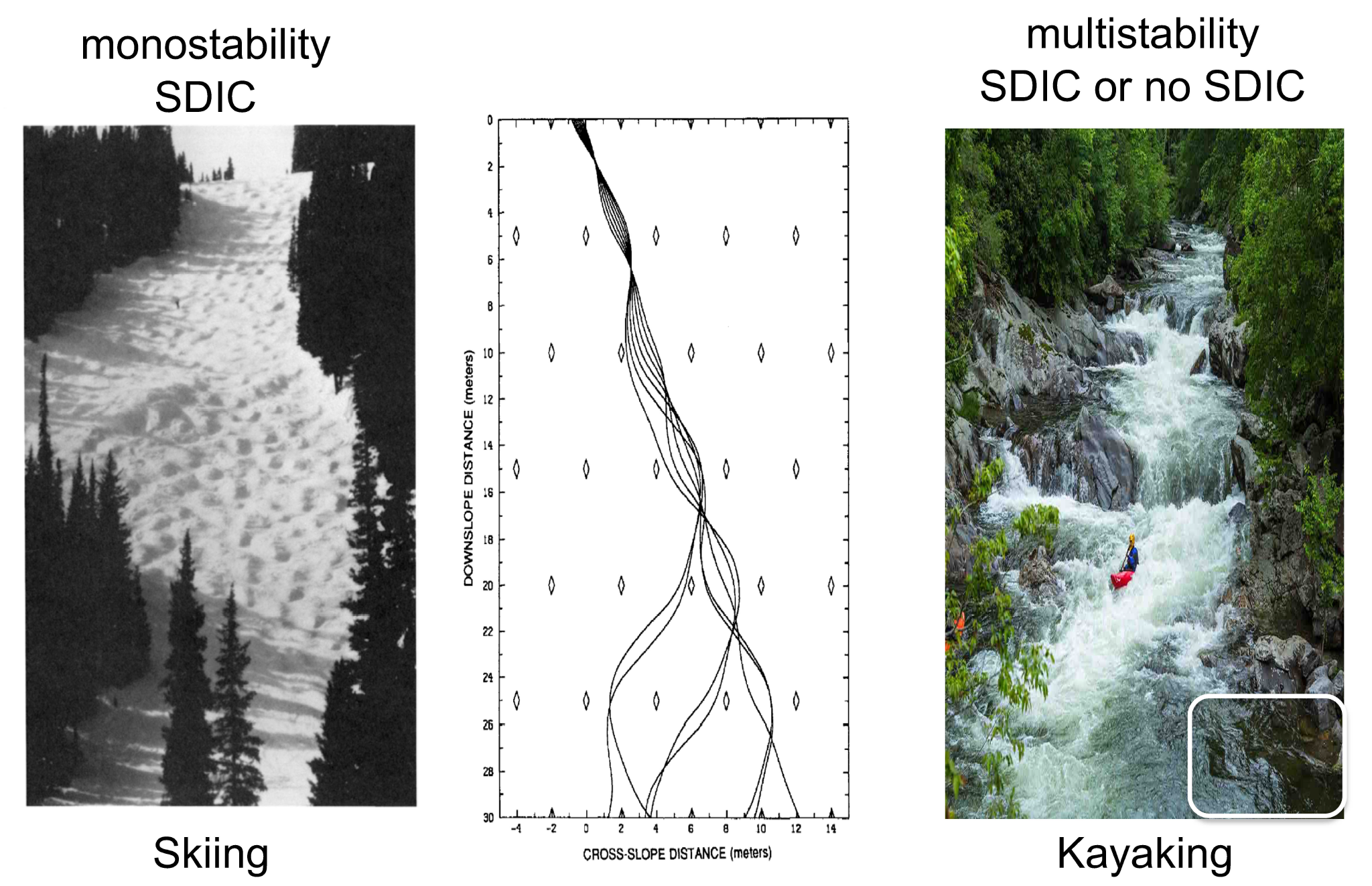

Since the sensitive dependence of solutions on initial conditions (SDIC), monostability, and multistability are the most important concepts in predictability studies using Lorenz models[1][2][3][4][5][6], to help readers, they are first illustrated using real-world analogies of skiing and kayaking. To explain SDIC, the book entitled “The Essence of Chaos” by Lorenz [7], 1993 applied the activity of skiing (left in Figure 1) and developed an idealized skiing model for revealing the sensitivity of time-varying paths to initial positions (middle in Figure 1). Based on the left panel, when slopes are steep everywhere, SDIC always appears. This feature with a single type of solution is referred to as monostability.

In comparison, the right panel of Figure 1 for kayaking is used to illustrate multistability. In the photo, the appearance of strong currents and a stagnant area (outlined with a white box) suggests instability and local stability, respectively. As a result, when two kayaks move along strong currents, their paths display SDIC. On the other hand, when two kayaks move into a stagnant area, they become trapped, showing no typical SDIC (although a chaotic transient may occur[8]). Such features of SDIC or no SDIC suggest two types of solutions and illustrate the nature of multistability.

Figure 1. Skiing as used to reveal monostability (left and middle, Lorenz 1993 [7]) and kayaking as used to indicate multistability (right, courtesy of Shutterstock-Carol Mellema https://www.shutterstock.com/image-photo/kayaker-enjoys-whitewater-sinks-smoky-mountains-649533271 (accessed 1 November 2022)). A stagnant area is outlined with a white box.

2. Non-Chaotic Weather Systems

The Lorenz 1969 (L69) model with forty-two, first order ODE was applied in order to study the multiscale predictability of weather. Although the L69 model is neither a low-order system nor a turbulence model (due to the lack of dissipative terms), major findings using the L69 model were indeed supported by studies using turbulence models [9][10]. By comparison, the Lorenz 1963 (L63) model has been used to illustrate the chaotic nature in weather and climate. Finite-dimensional chaotic responses revealed using the simple L63 model can be captured using rotating annulus experiments in the laboratory[11][12], illustrated by an analysis of weather maps (Figures 10.6 and 10.7 in [12]), and simulated using more sophisticated models (e.g., [13]). Based on ensemble runs using a weather model, the feature of local finite dimensionality [14][15][16] indicates a simple structure for instability (e.g., within a few dominant state space directions) (personal communication with Prof. Szunyogh) and, thus, suggests the occurrence of finite-dimensional chaotic responses.

As indicated by the title of Chapter 3 in [7], “Our Chaotic Weather”, and the title of [12], “Application of Chaos to Meteorology and Climate”, applying chaos theory for understanding weather and climate has been a focus for several decades [17][18]. By comparison, non-chaotic solutions have been previously applied for understanding the dynamics of different weather systems, including steady-state solutions for investigating atmospheric blocking (e.g.,[19][20]), limit cycles for studying 40-day intra-seasonal oscillations [21], quasi-biennial oscillations [22] and vortex shedding [23], and nonlinear solitary-pattern solutions for understanding morning glory (i.e., a low-level roll cloud, [24]). While additional detailed discussions regarding non-chaotic weather systems are being documented in a separate study, Table 1 provides a summary.

Table 1. Non-chaotic Solutions vs. Weather Systems.

| Type | Weather Systems | References |

|---|---|---|

| Steady-state Solutions | Atmospheric blocking | [19][20] |

| Limit Cycles | 40-day intra-seasonal oscillations | [21] |

| Quasi-biennial oscillations | [22] | |

| Vortex shedding | [23] | |

| Nonlinear solitary-pattern solutions | Morning glory | [24] |

3. Suggested Future Tasks

Numerous interesting studies in nonlinear dynamics exist and many of them have the potential to improve our understanding of weather and climate. Here, since suggested future tasks and additional studies and concepts will be covered in the future, only a few studies are discussed. Based on the above discussions, an effective classification of chaotic and non-chaotic solutions may identify systems with better predictability. Such a goal may be achieved by applying or extending existing tools, including the recurrence analysis method, the kernel principal component analysis method, the parallel ensemble empirical mode decomposition method, etc. (e.g., [25][26][27][28]). On the other hand, to separate chaotic and non-chaotic attractors, the detailed attractor basin for each attractor should be determined. Then, it becomes feasible to address final state sensitivity and intra-transitivity, as defined in Table 1 of [5]. Whether or not the number of attractors in our weather is finite is another interesting but challenging question. Given a specific system that possesses infinite attractors, the detection of “megastability” and “extreme multistability” that correspond to countable and uncountable attractors [29], respectively, further increases the level of the challenge. In addition to three types of solutions (i.e., steady-state, chaotic, and limit cycle solutions) and two kinds of attractor coexistence, homoclinic phenomena (e.g., homoclinic bifurcation, homoclinic tangencies, and homoclinic chaos), which have been intensively studied within low-order systems, deserve to be explored in high-dimensional systems (e.g., using the GLM with nine modes or higher) [30][31][32].

There is no doubt that the “butterfly effect”, originally derived from the Lorenz’s 1963 study [1][7], is a fascinating idea that has inspired many researchers to devote their time and effort to related research. For example, Lorenz’s attractor and Lorenz-type attractors (that are associated with Lorenz and Shilnikov types of saddle points, respectively) [7][33][34][35][36][37] have been rigorously examined within dynamical systems (e.g., the L63 model and the Shimizu-Morioka model [33]). Among the three kinds of butterfly effects classified by Shen et al., 2022 [38], the first kind of butterfly effect with SDIC is well accepted, while the second kind of butterfly effect remains a metaphor. Thus, there is a definite need to finally answer the following question: “Can a butterfly flap cause a tornado in Texas?”. Stated more robustly, can a small perturbation create a coherent larger scale feature at large distances? If so, what are the sizes and intensities that can produce such a feature and at what distances? All of the above questions are the subject of future studies.

References

- Lorenz, E.N. Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1963, 20, 130–141.

- Lorenz, E.N. Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set off a Tornado in Texas? In Proceedings of the 139th Meeting of AAAS Section on Environmental Sciences, New Approaches to Global Weather, GARP, AAAS, Cambridge, MA, USA, 29 December 1972.

- Lorenz, E.N. The predictability of a flow which possesses many scales of motion. Tellus 1969, 21, 289–307.

- Shen, B.-W. Aggregated Negative Feedback in a Generalized Lorenz Model. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2019, 29, 1950037.

- Shen, B.-W.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Zeng, X.; Baik, J.-J.; Faghih-Naini, S.; Cui, J.; Atlas, R. Is Weather Chaotic? Coexistence of Chaos and Order within a Generalized Lorenz Model. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 2, E148–E158.

- Shen, B.-W.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Zeng, X.; Baik, J.-J.; Faghih-Naini, S.; Cui, J.; Atlas, R.; Reyes, T.A. Is Weather Chaotic? Coexisting Chaotic and Non-Chaotic Attractors within Lorenz Models. In Proceedings of the 13th Chaos International Conference CHAOS 2020, Florence, Italy, 9–12 June 2020; Skiadas, C.H., Dimotikalis, Y., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Complexity. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021.

- Lorenz, E.N.. The Essence of Chaos; University ofWashington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993; pp. 227.

- Yorke, J.; Yorke, E. Metastable chaos: The transition to sustained chaotic behavior in the Lorenz model. J. Stat. Phys. 1979, 21, 263–277.

- Leith, C.E. Atmospheric predictability and two-dimensional turbulence. J. Atmos. Sci. 1971, 28, 145–161.

- Leith, C.E.; Kraichnan, R.H. Predictability of turbulent flows. J. Atmos. Sci. 1972, 29, 1041–1058.

- Ghil, M.; Read, P.; Smith, L. Geophysical flows as dynamical systems: The influence of Hide’s experiments. Astron. Geophys. 2010, 51, 4.28–4.35.

- Read, P. Application of Chaos to Meteorology and Climate. In The Nature of Chaos; Mullin, T., Ed.; Clarendo Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 222–260.

- Legras, B.; Ghil,M. Persistent anomalies, blocking, and variations in atmospheric predictability. J. Atmos. Sci. 1985, 42, 433–471.

- Patil, D.J.; Hunt, B.R.; Kalnay, E.; Yorke, J.A.; Ott, E. Local low-dimensionality of atmospheric dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 5878–5881.

- Oczkowski, M.; Szunyogh, I.; Patil, D.J. Mechanisms for the Development of Locally Low-Dimensional Atmospheric Dynamics. J. Atmos. Sci. 2005, 62, 1135–1156.

- Ott, E.; Hunt, B.R.; Szunyogh, I.; Corazza, M.; Kalnay, E.; Patil, D.J.; Yorke, J. Exploiting Local Low Dimensionality of the Atmospheric Dynamics for Efficient Ensemble Kalman Filtering. 2002. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.physics/0203058 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Zeng, X.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Eykholt, R. Chaos theory and its applications to the atmosphere. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1993, 74, 631–644.

- Ghil, M. A Century of Nonlinearity in the Geosciences. Earth Space Sci. 2019, 6, 1007–1042.

- Charney, J.G.; DeVore, J.G. Multiple flow equilibria in the atmosphere and blocking. J. Atmos. Sci. 1979, 36, 1205–1216.

- Crommelin, D.T.; Opsteegh, J.D.; Verhulst, F. Amechanismfor atmospheric regime behavior. J. Atmos. Sci. 2004, 61, 1406–1419.

- Ghil, M.; Robertson, A.W. “Waves” vs. “particles” in the atmosphere’s phase space: A pathway to long-range forecasting? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99 (Suppl. 1), 2493–2500.

- Renaud, A.; Nadeau, L.-P.; Venaille, A. Periodicity Disruption of a Model Quasibiennial Oscillation of EquatorialWinds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 214504.

- Ramesh, K.; Murua, J.; Gopalarathnam, A. Limit-cycle oscillations in unsteady flows dominated by intermittent leading-edge vortex shedding. J. Fluids Struct. 2015, 55, 84–105. [

- Goler, R.A.; Reeder, M.J. The generation of the morning glory. J. Atmos. Sci. 2004, 61, 1360–1376.

- Reyes, T.; Shen, B.-W. A Recurrence Analysis of Chaotic and Non-Chaotic Solutions within a Generalized Nine-Dimensional Lorenz Model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 125, 1–12.

- Cui, J.; Shen, B.-W. A Kernel Principal Component Analysis of Coexisting Attractors within a Generalized Lorenz Model. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 146, 110865.

- Wu, Y.-L.; Shen, B.-W. An evaluation of the parallel ensemble empirical mode decomposition method in revealing the role of downscaling processes associated with African easterly waves in tropical cyclone genesis. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2016, 33, 1611–1628.

- Shen, B.-W.; Cheung, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, F.; Kao, D. Parallel Implementation of the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (PEEMD) and Its Application for Earth Science Data Analysis. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2017, 19, 49–57.

- Jafari, S.; Rajagopal, K.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Pham, V.-T. Simplest Megastable Chaotic Oscillator. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2019, 29, 1950187.

- Shilnikov, L.P. On a new type of bifurcation of multi-dimensional dynamical systems. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1969, 10, 1368–1371.

- Gonchenko, S.V.; Turaev, D.V.; Shilnikov, L.P. Dynamical phenomena in multidimensional systems with a structurally unstable homoclinic Poincar6 curve. Russ. Acad. Sci. Dokl. Mat. 1993, 47, 410–415.

- Belhaq, M.; Houssni, M.; Freire, E.; Rodriguez-Luis, A.J. Asymptotics of Homoclinic Bifurcation in a Three-Dimensional System. Nonlinear Dyn. 2000, 21, 135–155.

- Shimizu, T.; Morioka, N. On the bifurcation of a symmetric limit cycle to an asymmetric one in a simple model. Phys. Lett. A 1980, 76, 201–204.

- Shil’nilov, A.L. On bifurcations of a Lorenz-like attractor in the Shimizu-Morioka system. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1992, 62, 332–346.

- Shil’nikov, A.L.; Shil’nikov, L.P.; Turaev, D.V. Normal Forms and Lorenz Attractors. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1993, 3, 1123–1139.

- Gonchenko, S.; Kazakov, A.; Turaev, D.; Shilnikov, A.L. Leonid Shilnikov and mathematical theory of dynamical chaos. Chaos 2022, 32, 010402.

- Simonnet, E.; Ghil, M.; Dijkstra, H. Homoclinic bifurcation in the quasi-geostrophic double-gyre circulation. J. Mar. Res. 2005, 63, 931–956.

- Shen, B.-W.; Pielke, R.A., Sr.; Zeng, X.; Cui, J.; Faghih-Naini, S.; Paxson, W.; Atlas, R. Three Kinds of Butterfly Effects within Lorenz Models. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1250–1259.