The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893, when the Liberals appeared reluctant to endorse working-class candidates, representing the interests of the majority. A sitting independent MP and prominent union organiser, Keir Hardie, became its first chairman. The party was positioned to the left of Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Representation Committee, which was founded in 1900 and soon renamed the Labour Party, and to which the ILP was affiliated from 1906 to 1932. In 1947, the organisation's three parliamentary representatives defected to the Labour Party, and the organisation rejoined Labour as Independent Labour Publications in 1975.

- political party

- liberals

- ilp

1. Organisational History

1.1. Background

As the nineteenth century came to a close, working-class representation in political office became a great concern for many Britons. Many who sought the election of working men and their advocates to the Parliament of the United Kingdom saw the Liberal Party as the main vehicle for achieving this aim. As early as 1869, a Labour Representation League had been established to register and mobilise working-class voters on behalf of favoured Liberal candidates.

Many trade unions themselves became concerned with gaining parliamentary representation to advance their legislative aims. From the 1870s a series of working-class candidates financially supported by trade unions were accepted and supported by the Liberal Party. The federation of British unions, the Trades Union Congress (TUC), formed its own electoral committee in 1886 to further advance its electoral goals.

Many socialist intellectuals, particularly those influenced by Christian socialism and similar notions of the ethical need for a restructuring of society, also saw the Liberals as the most obvious means for obtaining working-class representation. Within two years of its foundation in 1884, the gradualist Fabian Society officially committed itself to a policy of permeation of the Liberal Party.

A number of so-called "Lib-Lab" candidates were subsequently elected Members of Parliament by this alliance of trade unions and radical intellectuals working within the Liberal Party.[1]

The idea of working with the middle-class Liberal Party to achieve working-class representation in parliament was not universally accepted, however. Marxist socialists, believing in the inevitability of class struggle between the working-class and the capitalist class, rejected the idea of workers making common cause with the petty bourgeois Liberals in exchange for scraps of charity from the legislative table. The orthodox British Marxists established their own party, the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) in 1881.

Other socialist intellectuals, despite not sharing the concept of class struggle were nonetheless frustrated with the ideology and institutions of the Liberal Party and the secondary priority which it appeared to give to its working-class candidates. Out of these ideas and activities came a new generation of activists, including Keir Hardie, a Scot who had become convinced of the need for independent labour politics while working as a Gladstonian Liberal and trade union organiser in the Lanarkshire coalfield. Working with SDF members such as Henry Hyde Champion and Tom Mann he was instrumental in the foundation of the Scottish Labour Party in 1888.

In 1890, the United States imposed a tariff on foreign cloth which led to a general cut in wages throughout the British textile industry. There followed a strike in Bradford, the Manningham Mills strike, which produced as a by-product the Bradford Labour Union, an organisation which sought to function politically independently of either major political party. This initiative was replicated by others in Colne Valley, Halifax, Huddersfield and Salford. Such developments showed that working-class support for separation from the Liberal Party was growing in strength.

Further arguments for the formation of a new party were to be found in Robert Blatchford's newspaper The Clarion, founded in 1891, and in Workman's Times, edited by Joseph Burgess. The latter collected some 3,500 names of those in favour of creating a party of labour independent from the existing political organisations.

In the 1892 general election, held in July, three working men were elected without support from the Liberals, Keir Hardie in South West Ham, John Burns in Battersea, and Havelock Wilson in Middlesbrough, the last of whom actually faced Liberal opposition. Hardie owed nothing to the Liberal Party for his election, and his critical and confrontational style in Parliament caused him to emerge as a national voice of the labour movement.

1.2. Founding Conference

At a TUC meeting in September 1892, a call was issued for a meeting of advocates of an independent labour organisation. An arrangements committee was established and a conference called for the following January. This conference was chaired by William Henry Drew and was held in Bradford 14–16 January 1893 at the Bradford Labour Institute, operated by the Labour Church.[2] It proved to be the foundation conference of the Independent Labour Party and MP Keir Hardie was elected as its first chairman.[3]

About 130 delegates were in attendance at the conference, including in addition to Hardie such socialist and labour worthies as Alderman Ben Tillett, author George Bernard Shaw, and Edward Aveling, son-in-law of Karl Marx.[4] Some 91 local branches of the Independent Labour Party were represented, joined by 11 local Fabian Societies, four branches of the Social Democratic Federation, and individual representatives of a number of other socialist and labour groups.[4] German Socialist leader Edward Bernstein was briefly permitted to address the gathering to pass along the best wishes for success from the Social Democratic Party of Germany.[4]

A proposal was made by a Scottish delegate, George Carson, to name the new organisation the "Socialist Labour Party", but this was defeated by a large margin by a counterproposal reaffirming the name "Independent Labour Party", moved by the logic that there were large numbers of workers not yet prepared to formally accept the doctrine of socialism who would nonetheless be willing to join and work for an organisation "established for the purpose of obtaining the independent representation of labour".[4]

Despite the apparent timidity in naming the organisation, the inaugural conference overwhelmingly accepted that the object of the party should be "to secure the collective and communal ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". The party's programme called for a range of progressive social reforms, including free "unsectarian" education "right up to the universities", the provision of medical treatment and school feeding programmes for children, housing reform, the establishment of public measures to reduce unemployment and provide aid to the unemployed, a minimum-wage law, welfare programmes for orphans, widows, the elderly, the disabled, and the sick, the abolition of child labour, the abolition of overtime and piecework, and an eight-hour workday.[5]

The keynote address of the foundation conference was delivered by Keir Hardie, who observed that the Labour Party was "not an organisation but rather 'the expression of a great principle,' since it 'had neither programme nor constitution".[4] Hardie emphasised the fundamental demand of the new organisation as being the achievement of economic freedom and called for a party structure which gave full autonomy to every locality, and only seeking to bind these groups "to such central and general principles as were indispensable to the progress of the movement".[4]

The conference also established the basic organisational structure of the new party. Annual Conferences, composed of delegates from each local unit of the organisation, were declared the "supreme and governing authority of the party". A Secretary was to be elected, to serve under the direct control of a central body known as the National Administrative Committee (NAC). This NAC was in turn to be made up of regionally appointed delegates who were in theory confined to act according to the instructions given them by branch conferences.[6]

1.3. Early Years

The new party was founded in a social environment of great hope and expectation. However, the first few years were difficult. The direction of the party, its leadership and organisation were heavily contested and the expected electoral progress did not emerge.

The party did not fare well in its first major test of national support, the 1895 general election. With the NAC taking a lead in organising the party's contests, and with finance tight just 28 candidates ran under the ILP banner. A special conference decided that support could be given to either ILP or SDF candidates, which brought a further four contests into the picture. None was elected, however, with even the popular party leader Keir Hardie going to defeat in a straight fight with the Conservatives. The electoral debacle of 1895 marked an end to the unbridled optimism which had attended the party's foundation.

From its beginning, the ILP was never a homogeneous unit, but rather attempted to act as a "big tent" party of the working class, advocating a rather vague and amorphous socialist agenda. Historian Robert E. Dowse has observed:

"From the beginning the ILP attempted to influence the trade unions to back a working-class political party: they sought, as Henry Pelling states: 'collaboration with trade unionists with the ultimate object of tapping trade union funds for the attainment of Parliamentary power.' The socialism of the ILP was ideal for achieving this end; lacking as it did any real theoretical basis it could accommodate practically anything a trade unionist was likely to demand. Fervent and emotional, the socialism of the ILP could accommodate, with only a little strain, temperance reform, Scottish nationalism, Methodism, Marxism, Fabian gradualism, and even a variety of Burkean conservatism. Although the mixture was a curious one, it did have the one overwhelming virtue of excluding nobody on dogmatic grounds, a circumstance, on the left and at the time, which cannot be lightly dismissed."[7]

Of course in a party of loose and diverse opinions, the essential nature of the organisation and its programme would always remain a matter of debate. Initial decisions about party organisation were rooted in an idea of strict democracy. These arguments did have some impact, as the conference held to set policy prior to the 1895 general election and the abolition of the position of party "President" in 1896 testified to the power of such arguments. Nonetheless, the NAC came to possess considerable power over the party's activities, including hegemonistic control over crucial matters such as electoral decisions and relations with other parties. The electoral defeat of 1895 hastened the establishment of centralising and anti-democratic practices of this kind.

In the last years of the 19th century, four figures emerged on the NAC who remained at the centre of the party shaping its direction for the next 20 years. In addition to the beloved party leader Keir Hardie came the Scot Bruce Glasier, elected to the NAC in 1897 and succeeding Hardie as Chairman in 1900; Philip Snowden, an evangelical socialist from the West Riding, and Ramsay MacDonald, whose adhesion to the ILP had been secured in the wake of his disillusionment with the Liberal Party over its rejection of a trade unionist candidate in the 1894 Sheffield Attercliffe by-election. While there were substantial personal tensions between the four, they shared a fundamental view that the party should seek alliance with the unions and rather than an ideology-based socialist unity with the Marxist Social Democratic Federation.

Following the failure of 1895, this leadership became reluctant to overextend the party by running in too many electoral races. By 1898 the decision was formally made to restrict electoral contests to those where a reasonable performance could be expected rather than putting forward as many candidates as possible to maximise exposure for the party and to accumulate a maximum total vote.

The relationship with the trade unions was also problematic. In the 1890s the ILP was lacking in alliances with the trade union organisations. Individual rank and file trade unionists could be persuaded to join the party out of a political commitment shaped by their industrial experiences, but connection with top leaderships was lacking.

The ILP played a central role in the formation of the Labour Representation Committee in 1900, and when the Labour Party was formed in 1906, the ILP immediately affiliated to it. This affiliation allowed the ILP to continue to hold its own conferences and devise its own policies, which ILP members were expected to argue for within the Labour Party. In return, the ILP provided a good part of Labour's activist base during its early years.

1.4. The Party Matures

The emergence and growth of the Labour Party, a federation of trade unions with the socialist intellectuals of the ILP, helped its constituent parts develop and grow. In contrast to the doctrinaire Marxism of the SDF and its even more orthodox offshoots like the Socialist Labour Party and the Socialist Party of Great Britain, the ILP had a loose and inspirational flavour that made it relatively more easy to attract newcomers. Victor Grayson recalled a 1906 campaign in the Colne Valley which he was proud to have conducted "like a religious revival," without reference to specific political problems.[8] Future party chairman Fenner Brockway later recounted the revivalist mood of the gatherings of his local ILP branch gathering in 1907:

"On Sunday nights a meeting was conducted rather on the lines of the Labour Church Movement—we had a small voluntary orchestra, sang Labour songs and the speeches were mostly Socialist evangelism, emotion in denunciation of injustice, visionary in their anticipation of a new society."[9]

While this inspirational presentation of socialism as a humanitarian necessity made the party accessible as a sort of secular religion or a means for the practical implementation of Christian principles in daily life, it bore with it the great weakness of being non-analytical and thus comparatively shallow. It also offered a political home for some of the women's franchise movement in the UK, the Liverpool branch appointing Alice Morrissey as the branch secretary (1907–08) and first female delegate to a regional Labour Representative Committee.[10] As the historian John Callaghan has noted, in the hands of Hardie, Glasier, Snowden and MacDonald socialism was little more than "a vague protest against injustice."[11] However, in 1909 the ILP laid the basis for the production of agitational material with the establishment of the National Labour Press.[12]

Still, the relationship between the ILP and the Labour Party was characterised by conflict. Many ILP members viewed the Labour Party as being too timid and moderate in their attempts at social reform, detached as it was from the socialist objective during its first years. Consequently, in 1912 came a split in which many ILP branches and a few leading figures, including Leonard Hall and Russell Smart, chose to amalgamate with the SDF of H. M. Hyndman in 1912 to found the British Socialist Party.

Until 1918, individuals could only join the Labour Party through an affiliated body, the most significant of which were the Fabian Society and the ILP. As a result, particularly from 1914, many individuals – particularly ones formerly active in the Liberal Party – joined the ILP, in order to become active in the Labour Party. While affiliated body membership was not required after 1918, the presence of MacDonald and other leading Labour Party figures in the ILP's leadership meant many converts to the Labour Party continued to join through the ILP, a process which continued until about 1925.[13]

1.5. The ILP and the Great War

On 11 April 1914 the party celebrated its 21st anniversary with a congress in Bradford. The party had grown well in the previous decade, standing with a membership of approximately 30,000.[14] The rank and file membership of the party as well as its leadership were pacifist, now as ever, having held from the beginning that war was "sinful".[15]

The guns of August 1914 shook every left organisation in Britain. As one observer later put it: "Hyndman and Cunningham Graham, Thorne and Clynes had sought peace while it endured, but now that war had come, well, Socialists and Trade Unionists, like other people had got to see it through."[16] With respect to the Labour Party, most of the members of the organisation's executive as well as most of the 40 Labour MPs in Parliament lent their support to the recruiting campaign for the Great War. Only one section held aloof—the Independent Labour Party.[17]

The ILP's insistence on standing by its long-held ethically based objections to militarism and war proved costly both in terms of its standing in the eyes of the general public as well as its ability to hold sway over the politicians who ran under its banner. A stream of its old Members of Parliament left the party over the ILP's refusal to support the British war effort. Among those breaking ranks were George Nicoll Barnes, J. R. Clynes, James Parker, George Wardle and G. H. Roberts.[17]

Others held true to the party and its principles. Ramsay MacDonald, a committed pacifist, immediately resigned the chairmanship of the Labour Party in the House of Commons. Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, W. C. Anderson, and a small group of like-minded radical pacifists, maintained an unflinching opposition to the government and its pro-war Labour allies.[17] The 1917 Russian Revolution Conference in Leeds called for "the complete independence of Ireland, India and Egypt".[18]

During the war the ILP's criticism of militarism was somewhat muted by public condemnation and periodic episodes of physical violence, which included a wild scene on 6 July 1918, during which an agitated group of discharged soldiers rushed an ILP meeting being addressed by Ramsay MacDonald in the Abbey Wood section of London.[19] Stewards at the door of the ILP meeting were overpowered by the mob, who in what was described as a "riotous scene" broke chairs and wielded their parts as weapons, seizing the auditorium and dispersing the socialists into the night.[19]

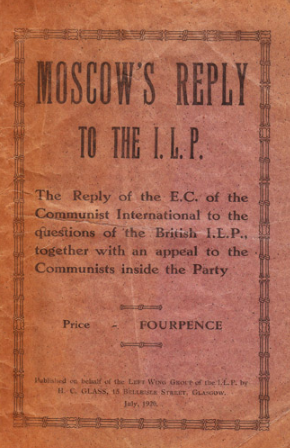

1.6. The ILP and the Third International

Following the termination of World War I in November 1918, the Second International was effectively relaunched and the question of whether the ILP should affiliate with this renewed Second International or with some other international grouping loomed large. The majority of ILP members saw the old Second International as hopelessly compromised by its support for the European bloodbath of 1914, and the ILP formally disaffiliated from the International in the spring of 1920. In January 1919, Moscow issued a call for the formation of a new Third International, a formation which held great appeal to a small section of the ILP's most radical members, including economist Emile Burns, journalist R. Palme Dutt, and the future Member of Parliament Shapurji Saklatvala, along with Charles Barber, Ernest H. Brown, Helen Crawfurd, C. H. Norman, and J. Wilson. They called themselves the Left Wing Group of the ILP.[20]

The conservative leadership of the ILP, notably Ramsay MacDonald and Philip Snowden, strongly opposed affiliation to the new Comintern. In opposition to them the radical wing of the ILP organised itself as a formal faction called the Left Wing Group of the ILP in an effort to move the ILP into the Communist International. The faction began to produce its own bi-weekly newspaper called The International, a four-page broadsheet published in Glasgow, and sent greetings to the conference which established a Communist Party of Great Britain, although they did not attend.[20]

In addition to cutting its ties with the Second International, the 1920 Annual Conference of the ILP directed its executive to contact the Swiss Socialist Party with a view to establishing an all-inclusive international which would join the internationalist left-wing socialist parties with their revolutionary socialist brethren of the new Moscow international. In a letter dated 21 May 1920, ILP chairman Richard Wallhead and National Council member Clifford Allen asked a further set of questions of the Comintern. The Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) was asked for its positions on such matters as demands for rigid adherence to its programme, applicability of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the Soviet system to Great Britain, and its view on the necessity of armed force as a universal principle.[21]

In July 1920 the fledgling Comintern gave an unequivocal reply: while the presence of communists inside the organisation was acknowledged, and their membership in a new Communist Party welcomed, there would be no joint organisation with those like "the Fabians, Ramsay MacDonald, and Snowden" who had previously made use of "the musty atmosphere of parliamentary work" and "petty concessions and compromises" on behalf of the labour movement:

[T]hese leaders have lost touch with the wide unskilled masses, with the toiling poor, they have become oblivious of the growth of capitalist exploitation and of the revolutionary aims of the proletariat. It seemed to them that because the capitalists treated them as equals, as partners in their transactions, the working class had secured equal rights with capital. Their own social standing secure and material position improved, they looked upon the world through the rose-coloured spectacles of a peaceful middle-class life. Disturbed in their peaceful trading with the representatives of the bourgeoisie by the revolutionary strivings of the proletariat they were the convinced enemies of the revolutionary aims of the proletariat.[22]

The ECCI instead made its appeal directly to "the communists of the Independent Labour Party", noting that "the revolutionary forces of England are split up" and urging them to unite with communist members of the British Socialist Party, the Socialist Labour Party, and radical groups in Wales and Scotland. "The emancipation of the British working class and of the working class of the whole world depends upon the Communist elements of England forming a single Communist Party", the ECCI declared.[23]

The agitation for affiliation to the Third International of Moscow came to a head in 1921 at the annual conference of the ILP. There an overwhelming vote of the party's branches voted not to affiliate with the Third International.[24] This decision was followed by the exit of the defeated radical faction, which immediately joined the CPGB.[20]

The "centrism" of the ILP, caught between the reformist politics of the Second International and the revolutionary politics of the Third International, led it to leading a number of other European socialist groups into the "Second and a Half International" between 1921 and 1923. The party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International between 1923 and 1933.[25]

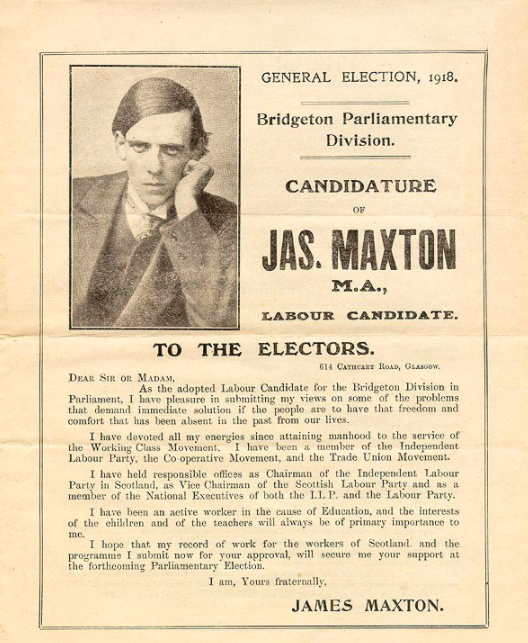

1.7. The ILP and Labour Party Governments (1922–1931)

At the 1922 general election several ILP members became MPs (including future ILP leader James Maxton) and the party grew in stature. The ILP provided many of the new Labour MPs, including John Wheatley, Emanuel Shinwell, Tom Johnston and David Kirkwood. However, the first Labour government, returned to office in 1924, proved to be hugely disappointing to the ILP. This came despite 30% of the cabinet holding ILP membership; of the most prominent of these figures, Ramsay MacDonald was removed as editor of the ILP's Socialist Review in 1925, and Philip Snowden resigned from the ILP in 1927.[13]

1928 policy conferences

The ILP's response to the first Labour government was to devise its own programme for government. Throughout 1928, the ILP developed a "Socialism in Our Time" platform, largely formulated by H. N. Brailsford, John A. Hobson and Frank Wise.[13] The programme consisted of eight policies:

- The Living Wage, incompletely applied

- A substantial increase of the Unemployment Allowance

- The nationalisation of banking, incompletely applied

- The bulk purchase of raw materials

- The bulk purchase of foodstuffs

- The nationalisation of power

- The nationalisation of transport

- The nationalisation of land

Of these eight policies, the living wage, the unemployment allowance, nationalisation of banking and the bulk purchase of raw materials and foodstuffs were the chief concern of the ILP.[26] Increasing the unemployment allowance and switching to bulk purchasing were to be done in the conventional way, but the method of paying the living wage differed from Labour practices. The ILP criticised the "Continental" method of paying wage allowances from employers' pools, which had been implemented in 1924 by Rhys Davies.[27] The ILP proposed to redistribute the national income, meeting the cost of the allowances by taxing high income earners.

The nationalisation of banking involved more significant changes to economic policy, and had nothing in common with Labour practices. The ILP proposed that once a Labour government took office it should hold an enquiry into the banking system that would prepare a detailed scheme for transferring the Bank of England to public control, revise the operation of the Bank Acts and ensure that "control of credit is exercised in the national interest and not in the interest of powerful financial groups" by making creditors shift entirely to cheques and possibly getting rid of gold reserves, thus ending the policy of deflation practised by the Treasury and the Bank of England.[28]

The Labour leadership did not support the programme. In particular, MacDonald objected to the slogan "Socialism In Our Time", as he viewed socialism as a gradual process. For the duration of the second Labour government (1929–31), 37 Labour MPs were sponsored by the ILP, but none were appointed to the cabinet. Instead, the group provided the left opposition to the Labour leadership.[13] The 1930 ILP conference decided that where their policies diverged from the Labour Party their MPs should break the whip to support the ILP policy.

1931 ILP Scottish Conference

It was becoming clearer that the ILP was diverging further away from the Labour Party and at the 1931 ILP Scottish Conference the issue of whether the party should still affiliate to Labour was discussed. It was decided to continue to do so, but only after Maxton himself intervened in the debate.

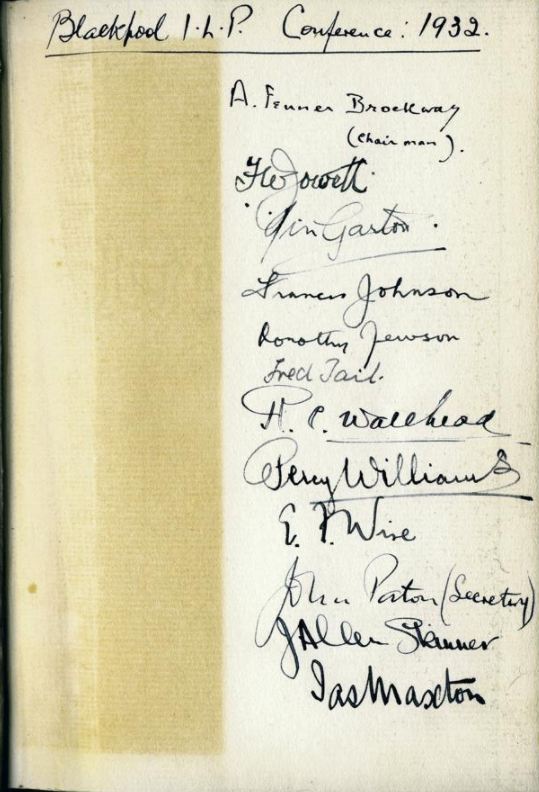

1.8. From Disaffiliation to the Second World War

At the 1931 general election the ILP candidates refused to accept the standing orders of the Parliamentary Labour Party and stood without Labour Party support. Five ILP members were returned to Westminster and created an ILP group outside the Labour Party. In 1932 a special conference of the ILP voted to disaffiliate from Labour. The same year the ILP co-founded the London Bureau of left-socialist parties, later called the International Revolutionary Marxist Centre or "Three-and-a-Half International", administered by the ILP and chaired by its leader, Fenner Brockway, for most of its existence.

The Labour left-winger Aneurin Bevan described the ILP's disaffiliation as a decision to remain "pure, but impotent". Outside the Labour Party the ILP went into decline. In just three years it lost 75% of its members, the total falling from 16,773 in 1932 to 4,392 in 1935,[29] as it lost adherents to the Labour Party, the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and the Trotskyists. Some members of the ILP who had chosen to remain within the Labour Party were instrumental in creating the Socialist League, while the majority of Scottish members left to form the Scottish Socialist Party[30] and members in Northern Ireland left en masse to form the Socialist Party of Northern Ireland.[31] In 1934 a breakaway group in the Northwest of England left to form the Independent Socialist Party.

The remaining ILP membership tended to be young and radical. They were particularly active in supporting the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War, and around twenty-five members and sympathisers, including George Orwell, went to Spain as members of an ILP Contingent of volunteers to assist the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), a sister party to the ILP in the Three-and-a-Half International.

From the mid-1930s onwards the ILP also attracted the attention of the Trotskyist movement, and various Trotskyist groups worked within it, notably the Marxist Group, of which C. L. R. James, Denzil Dean Harber and Ted Grant were members. There was also a group of ILP members, the Revolutionary Policy Committee, who were sympathetic to the CPGB and eventually left to join that party. From the late 1930s the ILP had the support of several key figures in the tiny Pan-Africanist movement in Britain, including George Padmore and Chris Braithwaite, as well as left-wing writers such as George Orwell, Reginald Reynolds and Ethel Mannin.

In 1939 the ILP wrote to the Labour Party requesting reaffiliation subject to a right to advocate its own policies where it had a "conscientious objection" to Labour policy. Labour refused to agree to this condition, stating that its usual rules for affiliation could not be waived for the ILP.[32]

1.9. World War II and Beyond

As in 1914, the ILP opposed World War II on ethical grounds, and turned to the left. One aspect of its leftist policies in this period was that it opposed the war-time truce between the major parties and actively contested Parliamentary elections. In one such contest, the Cardiff East by-election in 1942, this was with the result that Fenner Brockway, the ILP candidate, found himself opposed by a Conservative candidate for whom the local Communist Party actively campaigned.

The ILP still had some significant strength at the end of the war, but it went into crisis shortly afterwards. At the 1945 general election it retained three MPs, all in Glasgow, although only one of them had a Labour opponent. Its conference rejected calls to reaffiliate to the Labour Party. A major blow came in 1946 when the party's best known public spokesman, James Maxton MP, died. The ILP narrowly held his seat in the 1946 Glasgow Bridgeton by-election (against a Labour opponent). However, all its MPs defected to Labour at various stages in 1947, and the party was roundly defeated at the 1948 Glasgow Camlachie by-election, in a seat it had won easily only three years earlier. The party was never again able to win a significant vote in a parliamentary election.

Despite these blows, the ILP continued. Throughout the 1950s and into the early 1960s it pioneered opposition to nuclear weapons and sought to publicise ideas such as workers' control. It also maintained links with the remnants of its fraternal groups, such as the POUM, who were in exile, as well as campaigning for decolonisation.

In the 1970s, the ILP reassessed its views on the Labour Party, and in 1975 it renamed itself Independent Labour Publications and became a pressure group inside Labour.

2. List of Chairs

|

|

|

3. Conferences of the ILP

-

- Source: On-line Register of the ILP Archives at the British Library of Political and Economic Science, https://archive.today/20120716063644/http://library-2.lse.ac.uk/archives/handlists/ILP/ILP.html

Year Name Location Dates Delegates 1893 Founding Conference Bradford 14–16 January 120 1894 2nd Annual Conference Manchester 2–3 February 1895 3rd Annual Conference Newcastle upon Tyne 15–17 April 1896 4th Annual Conference Nottingham 6–7 April 1897 5th Annual Conference London 19–20 April 1898 6th Annual Conference Birmingham 11–12 April 1899 7th Annual Conference Leeds 3–4 April 1900 8th Annual Conference Glasgow 16–17 April 1901 9th Annual Conference Leicester 8–9 April 1902 10th Annual Conference Liverpool 31 March – 1 April 1903 11th Annual Conference York 13–14 April 1904 12th Annual Conference Cardiff 4–5 April 1905 13th Annual Conference Manchester 24–25 April 1906 14th Annual Conference Stockton On-Tees April 1907 15th Annual Conference Derby April 1908 16th Annual Conference Huddersfield 20–21 April 1909 17th Annual Conference Edinburgh 10–13 April 1910 18th Annual Conference London March 1911 19th Annual Conference Birmingham 17–18 April 1912 20th Annual Conference Merthyr Tydfil 8–9 April 1913 21st Annual Conference Manchester March 1914 22nd Annual Conference Bradford 1915 23rd Annual Conference Norwich 5–6 April 1916 24th Annual Conference Newcastle upon Tyne 23–24 April 1917 25th Annual Conference Leeds 8–10 April 1918 26th Annual Conference Leicester 1–2 April 1919 27th Annual Conference Huddersfield 19–22 April 1920 28th Annual Conference Glasgow 3–6 April 1921 29th Annual Conference Southport 26–29 March 1922 30th Annual Conference Nottingham 16–18 April 1923 31st Annual Conference London April 1924 32nd Annual Conference York April 1925 33rd Annual Conference Gloucester 10–14 April 1926 34th Annual Conference Whitley Bay 2–6 April 1927 35th Annual Conference Leicester 15–19 April 1928 36th Annual Conference Norwich 6–10 April 1929 37th Annual Conference Carlisle 30 March – 2 April 1930 38th Annual Conference Birmingham 19–22 April 1931 39th Annual Conference Scarborough 4–7 April 1932 40th Annual Conference Blackpool 26–29 March 1933 41st Annual Conference Derby 15–18 April 1934 42nd Annual Conference York 31 March – 3 April 1935 43rd Annual Conference Derby 20–23 April 1936 44th Annual Conference Keighly 11–14 April 1937 45th Annual Conference Glasgow 27–30 March 1938 46th Annual Conference Manchester 16–19 April 1939 47th Annual Conference Scarborough 8–10 April 1940 48th Annual Conference Nottingham 23–25 March 1941 49th Annual Conference Nelson, Lancashire 12–14 April 1942 50th Annual Conference Morecambe 4–6 April 1943 Jubilee Annual Conference Bradford 24–26 April 1944 52nd Annual Conference Leeds 8–10 April 1945 53rd Annual Conference Blackpool 31 March – 2 April 1946 54th Annual Conference Southport 20–22 April 1947 55th Annual Conference Ayr 5–7 April 1948 56th Annual Conference Southport 27–29 March 1949 57th Annual Conference Blackpool 16–18 April 1950 58th Annual Conference Whitley Bay 8–10 April 1951 59th Annual Conference Blackpool 24–26 March 1952 60th Annual Conference New Brighton 12–14 April 1953 61st Annual Conference Glasgow 17–19 April 1954 62nd Annual Conference Bradford April 1955 63rd Annual Conference Harrogate 9–11 April 1956 64th Annual Conference London 31 March – 2 April 1957 65th Annual Conference Whitley Bay 20–22 April 1958 66th Annual Conference Harrogate 5–7 April 1959 67th Annual Conference Morecambe 28–30 March 1960 68th Annual Conference Wallasey 16–18 April 1961 69th Annual Conference Scarborough 1–3 April 1962 70th Annual Conference Blackpool 21–23 April 1963 71st Annual Conference Bradford 13–15 April 1964 72nd Annual Conference Southport 28–30 March 1965 73rd Annual Conference Blackpool 17–19 April 1966 74th Annual Conference Blackpool 9–11 April 1967 75th Annual Conference Blackpool 25–27 March 1968 76th Annual Conference Morecambe 13–15 April 1969 77th Annual Conference Morecambe 5–7 April 1970 78th Annual Conference Morecambe 28–30 March 1971 79th Annual Conference Morecambe 10–12 April 1972 80th Annual Conference 1973 81st Annual Conference Scarborough 1974 82nd Annual Conference Leeds

- Source: On-line Register of the ILP Archives at the British Library of Political and Economic Science, https://archive.today/20120716063644/http://library-2.lse.ac.uk/archives/handlists/ILP/ILP.html

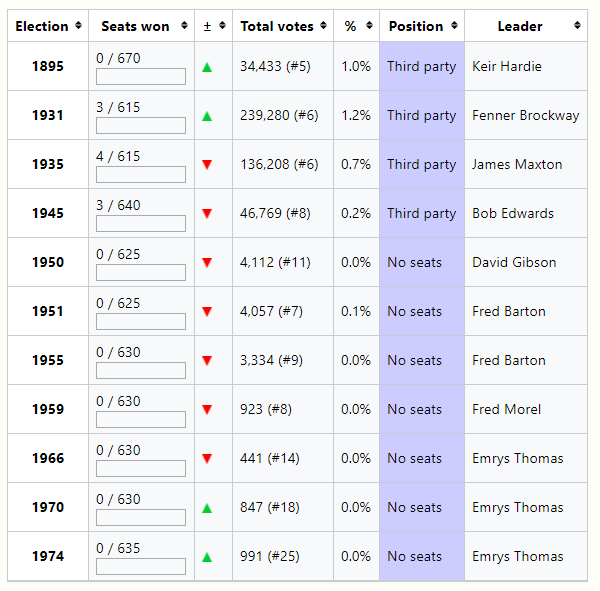

5. Election Results

References

- Henry Pelling, The Origins of the Labour Party. London: Macmillan, 1954, p. ??.

- Johnson, Neil (May 2015). 'So peculiarly its own': the theological socialism of the Labour Church (PhD). University of Birmingham. Retrieved 19 December 2019. https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/6000/

- David Howell, British Workers and the Independent Labour, 1888–1906, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984, pp. 471–484.

- "Labour Politics: Conference at Bradford," Glasgow Herald, vol. 111, no. 12 (14 January 1893), p. 9.

- Donald F. Busky, Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey.

- Howell, British Workers and the Independent Labour Party, pp. 301–327.

- Dowse, Left in the Centre, pp. 6–7.

- Fenner Brockway, Inside the Left. London: Allen and Unwin, 1942; p. 24. Cited in John Callaghan, Socialism in Britain Since 1884. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990, p. 67.

- Brockway, Inside the Left, p. 24, cited in Callaghan, Socialism in Britain, pp. 66–67.

- Suffrage Reader : Charting Directions in British Suffrage History.. Eustance, Claire., Ryan, Joan., Ugolini, Laura.. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. 2000. ISBN 978-1-4411-8885-4. OCLC 952932390. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/952932390

- Callaghan, Socialism in Britain, p. 67.

- "Independent Labour Party". LSE. http://archives.lse.ac.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=ILP. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Cline, Catherine Ann (1963). Recruits to Labour. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 102–103. https://archive.org/details/recruitstolabour00clin.

- Joseph Clayton, The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, 1884–1924. London: Faber and Gwyer, 1926; p. 165.

- Clayton, The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, p. 165.

- Clayton, The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, p. 166.

- Clayton, The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, p. 167.

- Adam Hochschild (2011). To End All Wars – a story of loyalty and rebellion, 1914–1918. Boston, MA: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 274. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780618758289.

- "Peace Cranks Routed," Daily Mirror [London], whole no. 4587 (8 July 1918), p. 2.

- Klugmann, James (1968). History of the Communist Party of Great Britain. London: Lawrence and Wishart. pp. 25–26; 162–166.

- R. C. Wallhead and Clifford Allen, "Letter to ECCI", 21 May 1920. Reprinted in Left Wing Group of the ILP, Moscow's Reply to the ILP: The Reply of the EC of the Communist International to the Questions of the British ILP, together with an Appeal to the Communists Inside the Party. Glasgow: H. C. Glass for the Left Wing Group of the ILP, July 1920, pp. 2–3.

- Moscow's Reply to the ILP, p. 6.

- Moscow's Reply to the ILP, pp. 31–32.

- Joseph Clayton, The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, 1884–1924. London: Faber and Gwyer, 1926, p. 179.

- Kowalski, Werner. Geschichte der sozialistischen arbeiter-internationale: 1923 – 19. Berlin: Dt. Verl. d. Wissenschaften, 1985. https://books.google.com/books?id=83QdPwAACAAJ

- Brockway, A. Fenner (30 November 1928). "The New Leader: the case for 'Socialism in Our Time'". The New Leader: p. 3.

- Hunter, E. E. (9 November 1928). "Tory or Communist: Rhys Davies and Family Allowances". The New Leader: p. 5.

- Brailsford, H. N. (3 August 1928). "Labour and the bankers: The tactics of attack". The New Leader: p. 4.

- Barry Winter, The ILP: Past and Present. Leeds: Independent Labour Publications, 1993. Page 23.

- Ben Pimlott, Labour and the Left in the 1930s, pp.100–101

- Ronaldo Munck and Bill Rolston, Belfast in the Thirties: An Oral History, pp. 145, 148

- The Times report, 13 July 1939, as recorded by George Orwell in his diary. http://orwelldiaries.files.wordpress.com/2009/07/the-times-13-7-39-page-8.jpg