The Biology of Mistletoe

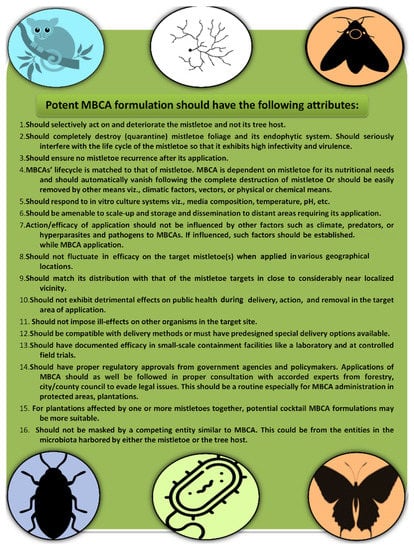

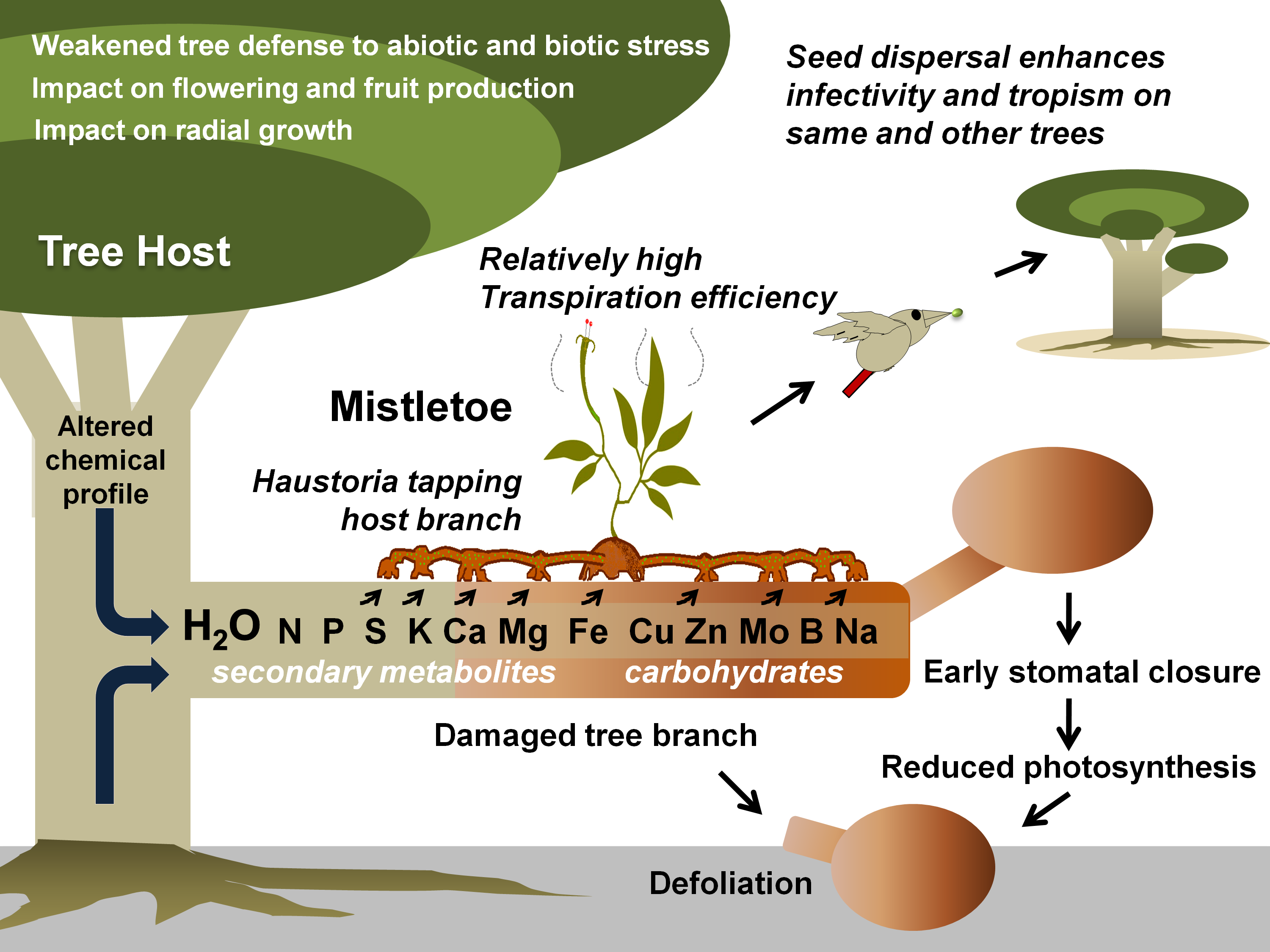

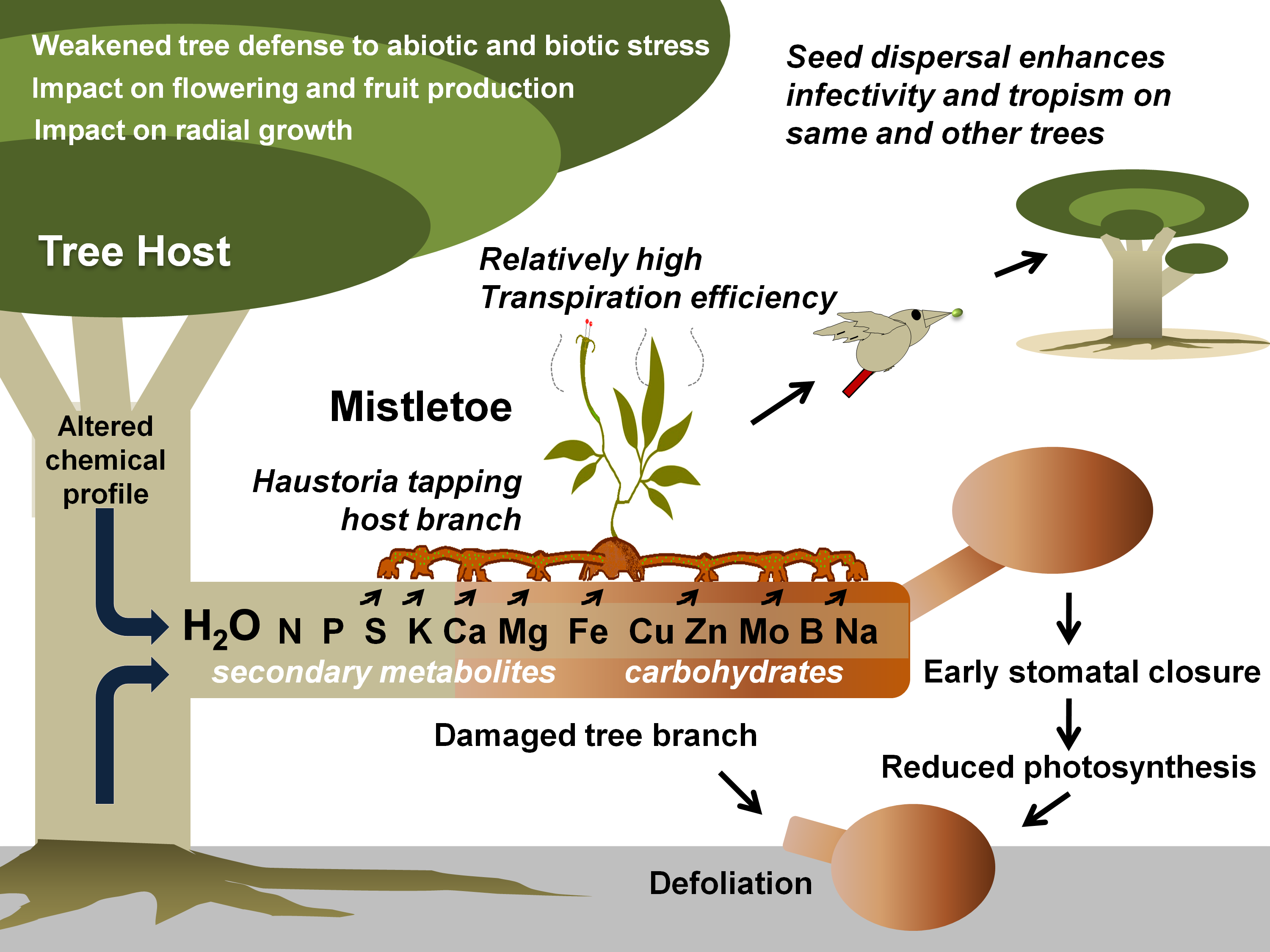

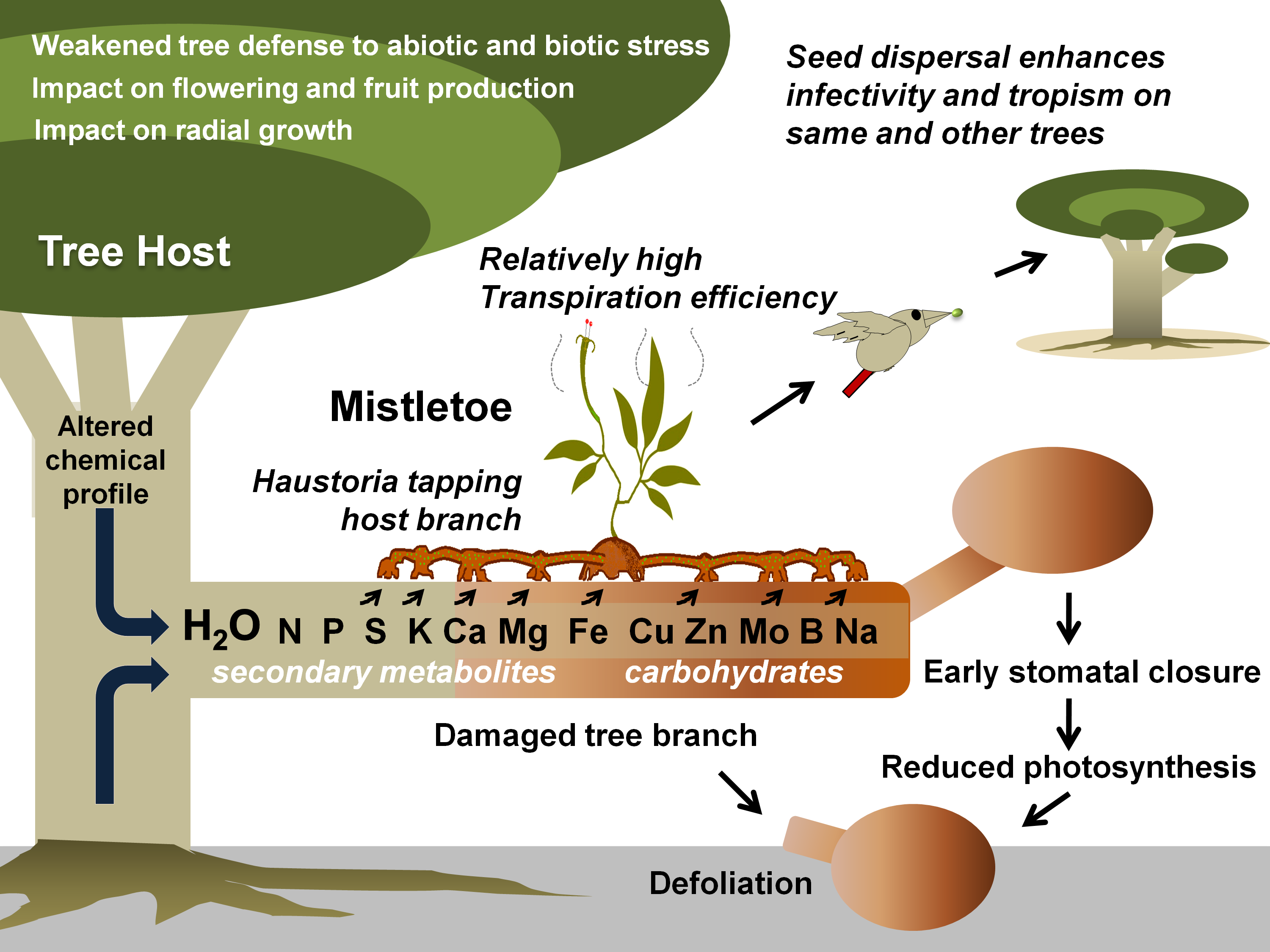

Mistletoes occur in the order Santalales, occupying the Loranthaceae (approx. 1000 species) and Viscaceae (approx. 550 species) [35]. Notably, the most notoriously damaging species in the are the honey-suckled (Dendrophthoe spp.), the showy (Helixanthera spp. and Psittacanthus spp.), and the red mistletoes (Tapinanthus spp.), while, among the Viscaceae are the Dwarf (Arceuthobium spp.), the American (Phoradendron spp.), and the European mistletoes (Viscum spp.) [36–63]. Mistletoes are characterized as hemiparasitic plants because of their reduced photosynthetic efficiency and the absence of a true rooting feature [18,64]. A false root-like appendage, known as a haustorium, attaches them to their host plants (mostly trees) and draws water and nutrients from them [65–67] (Figure 1). Generally, these haustorial connections lack a retranslocation system, meaning that the hemiparasites directly and exclusively associate with the host xylem, but exploitation of the host phloem is never reported [68–70]. By transpiring almost nine times as quickly as their hosts, mistletoes suppress their host’s ability to maintain water potential, thus causing early stomatal closure and reduced carbon assimilation [11,64,71–74]. Hosts find it difficult to maintain their water, carbohydrate, and mineral profiles, especially under drought and soil infertility conditions [75–78]. In addition, climate change may add to the host detriments since mistletoe may spread to new geographical regions, possibly infecting new hosts and increasing in infectivity [71,75,76]. Mistletoe seeds are dispersed predominantly by fruit-eating birds [79,80]. Some birds have coevolved with mistletoes exhibiting fruiting displays [81]. Mistletoes attract a narrow range of avian dispersers that have anatomical adaptations and dietary preferences specific to mistletoe fruits [66,81,82]. Some Viscaceae mistletoe in the genera Arceuthobium and Korthalsella are equipped with explosive dispersal mechanisms in their seeds [66]. Seed dispersal by these modes has possibly allowed mistletoe to spread to nearby potential host trees, as well as those in islands and continents far off [83–86]. Seed dispersal on a compatible tree host marks the start of the mistletoe life cycle and parasitism (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Mistletoe parasitism and impacts on a tree host. Specific mistletoe may parasitize its host by exploiting its branch(es) for water and various other resources, thereby limiting its photosynthetic potential, optimal growth, response to various stresses, and fruit or timber production. Gradually, infective spread (by haustorial connections and endophytic expansion) and growing infection instances (ensured by mistletoe seed dispersal) may lead to early senescence of the tree(s).

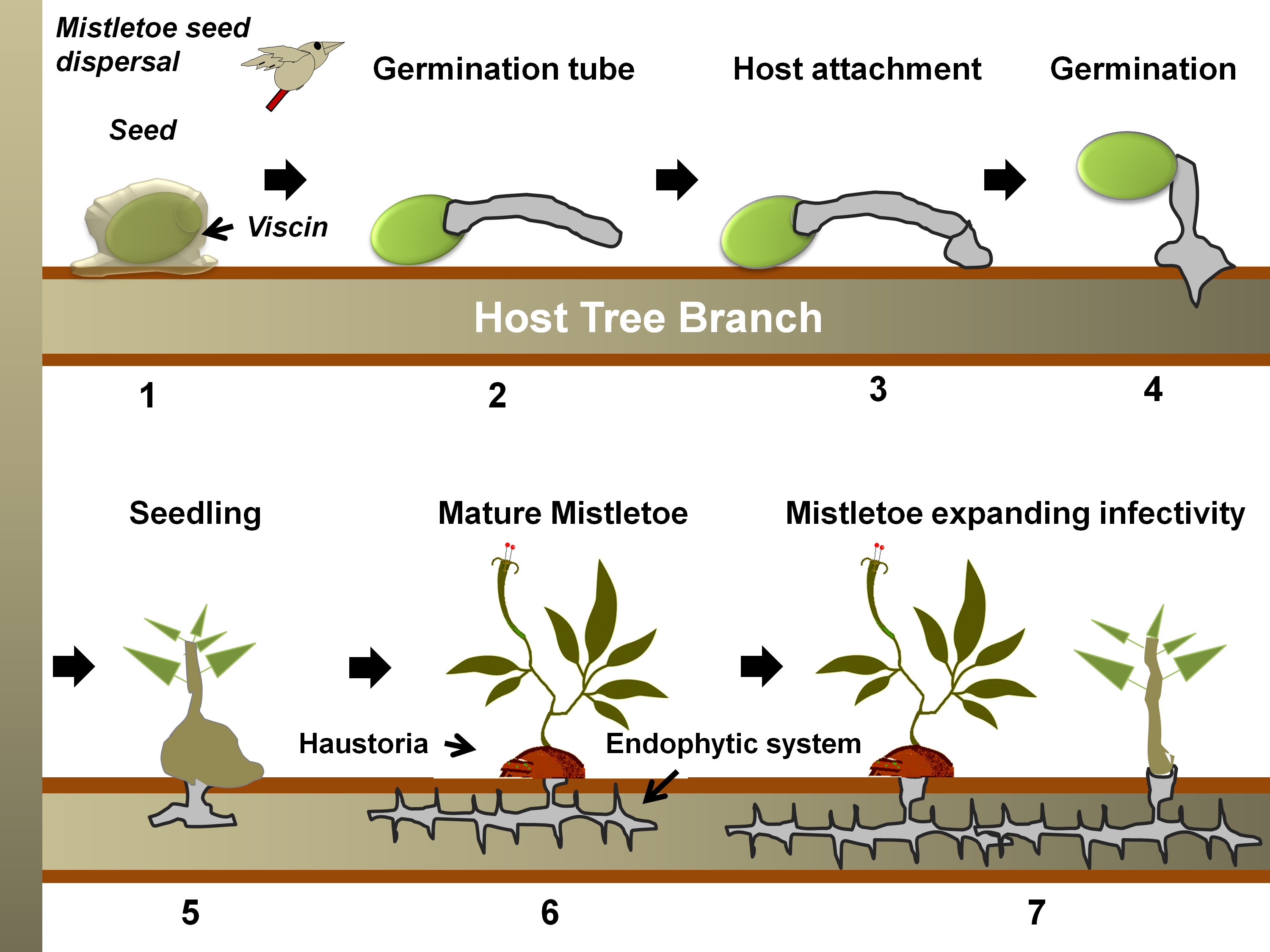

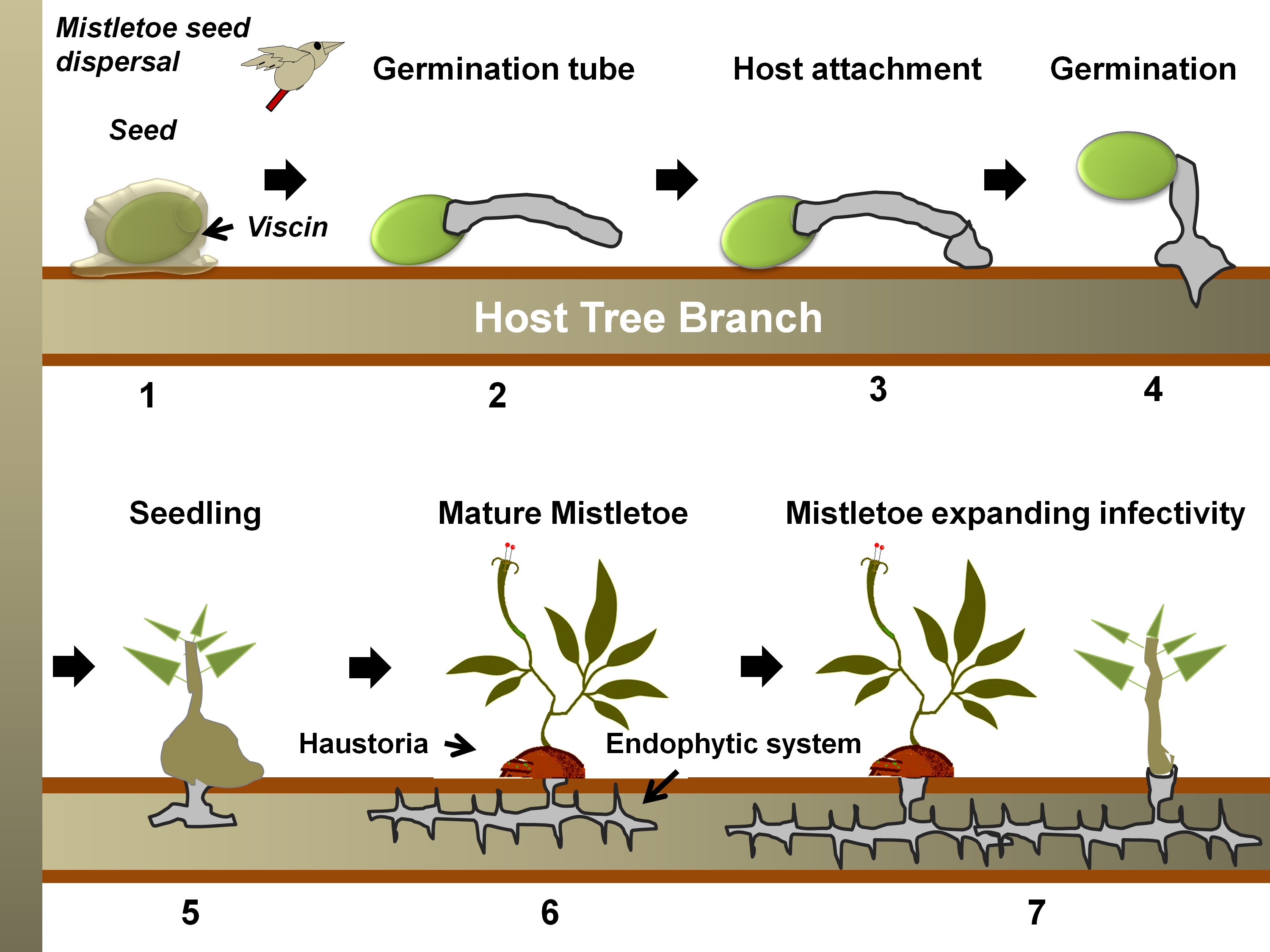

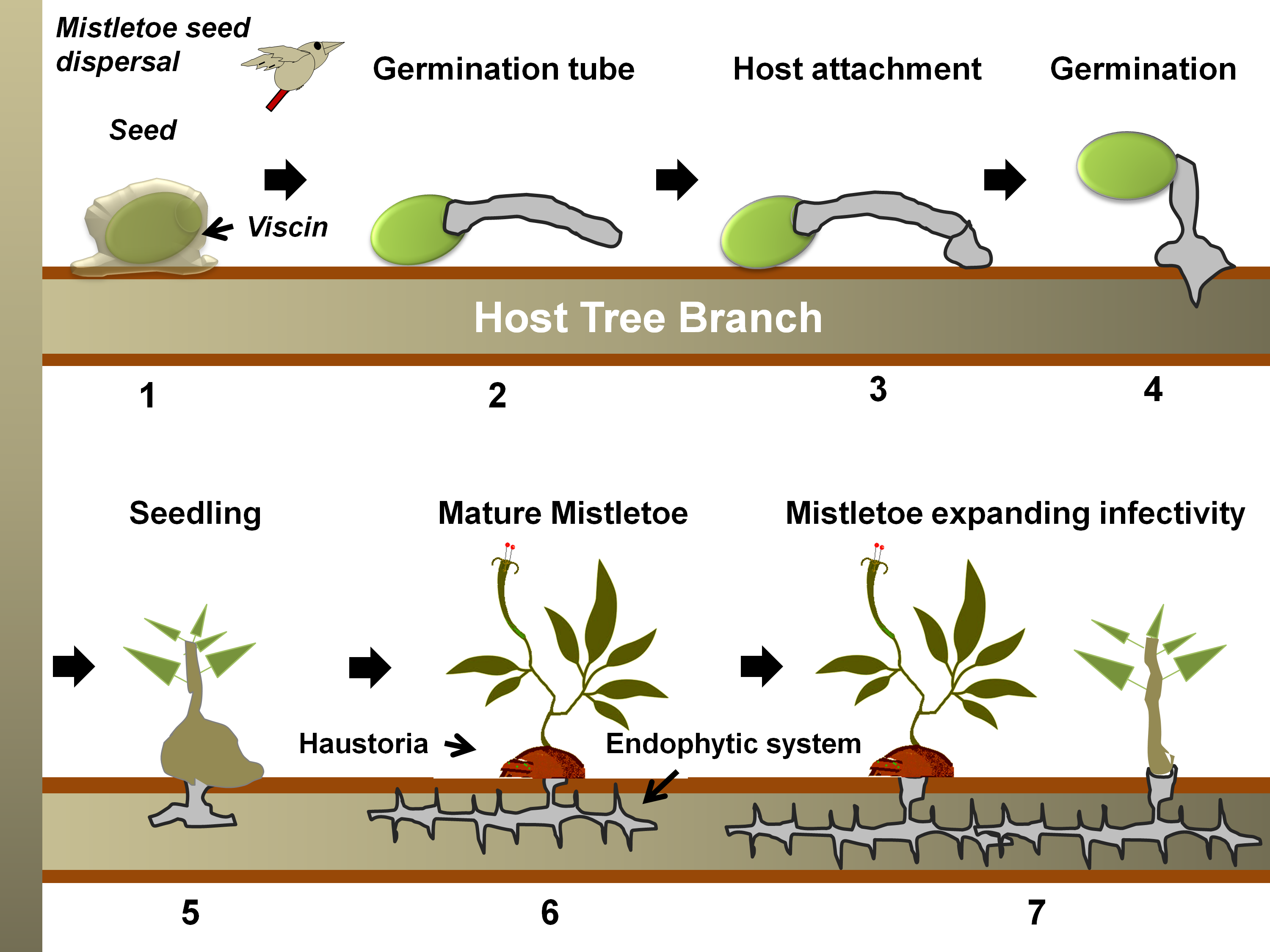

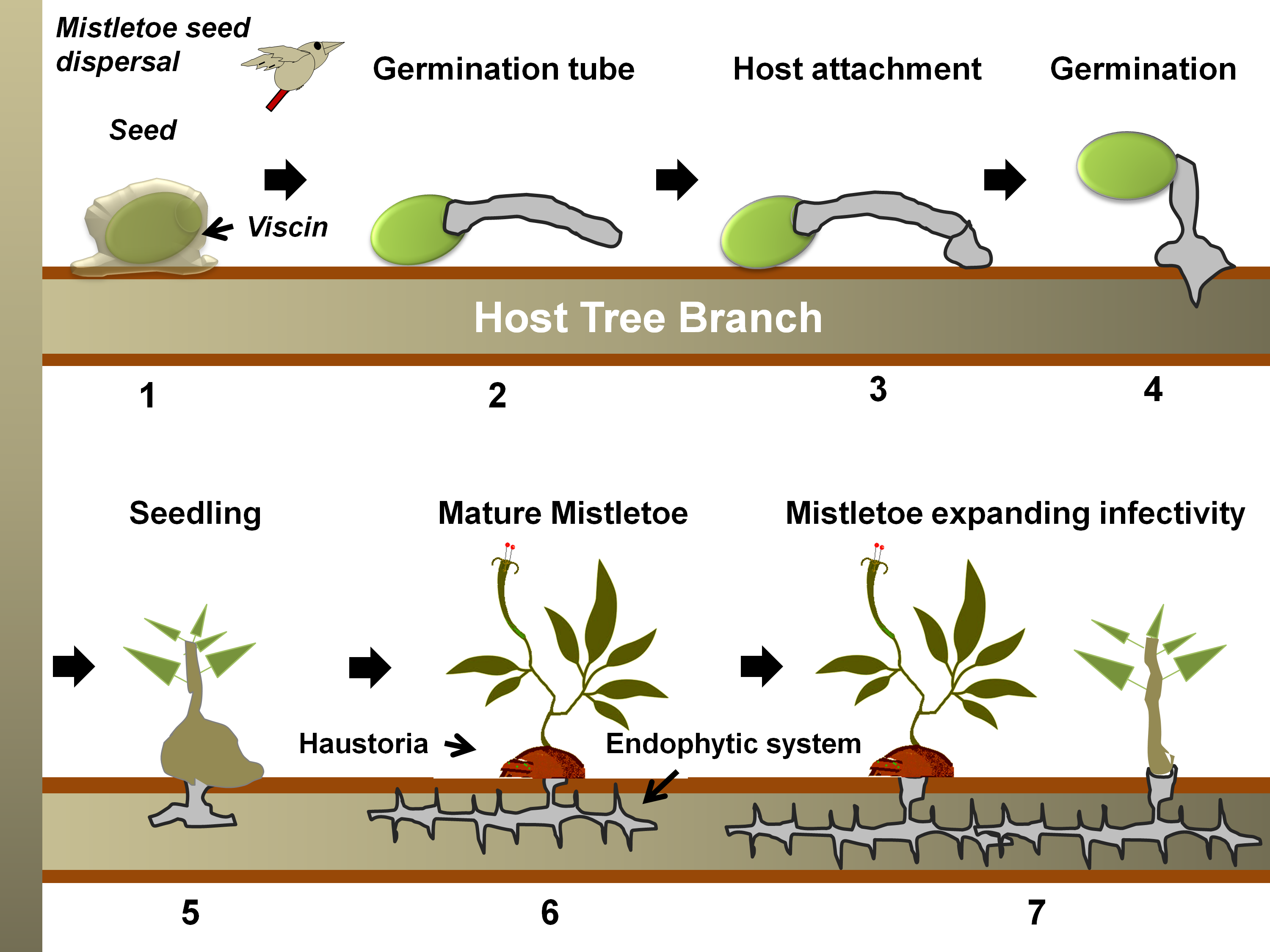

Figure 2. A generalized life cycle of a mistletoe parasite on a tree host. Following seed dispersal, a sticky materia l, viscin, over the seed coat ensures firm attachment to the host branch (in 1) [87,88]. Hypocotyl(s) from the seed then emerges and grows towards the bark (in 2), which eventually, while attaching to the bark (in 3), penetrates through it (in 4) [89]. Once the hypocotyl connects to the host xylem (in 5), it exploits the host for water, minerals, carbohydrates, and secondary metabolites (in 6) [83]. The endophytic system may expand as sinkers (or epicortical roots) along the host cambium, from which sporadically new shoots may emerge (in 7) and facilitate the heightening of infectivity [65].

l, viscin, over the seed coat ensures firm attachment to the host branch (in 1) [87,88]. Hypocotyl(s) from the seed then emerges and grows towards the bark (in 2), which eventually, while attaching to the bark (in 3), penetrates through it (in 4) [89]. Once the hypocotyl connects to the host xylem (in 5), it exploits the host for water, minerals, carbohydrates, and secondary metabolites (in 6) [83]. The endophytic system may expand as sinkers (or epicortical roots) along the host cambium, from which sporadically new shoots may emerge (in 7) and facilitate the heightening of infectivity [65].

1. Conventional Control Strategies and Integrated Pest Management Approaches

1.1. Physical Methods

Mistletoe was managed by people in forests and farms using various primitive methods. In the US, western dwarf mistletoe (

Arceuthobium campylopodum) predominantly affects Ponderosa and Jeffery pines in forests [

90,

142]. These mistletoes can reduce life expectancy and result in the poor growth of infected hosts, as well as a loss of their scenic and esthetic value [

90,

142]. Conventional practices such as pruning and thinning of the affected host parts have proven less helpful [

28,

143,

144,

145]. There are many concerns and problematic issues that also have hindered these methods [

90,

145]. Known practices that have shaped the integrated management regimens for the control of mistletoes have been categorized into direct and indirect approaches [

29,

90]. Direct methods include the individual removal of infected trees, branches, or mistletoe brooms, or installing buffer strips, and the use of hosts that can resist mistletoe parasitism [

90]. These methods could limit mistletoe spread and infection rates to some extent [

90]. The potential benefit of removing the infected branches in Scot pines (

Pinus sylvestris) aids in evading the inherent competition for water and nutrients within the host plant, which concomitantly results in improved tree health, such as elevated height, biomass growth, and diameter [

111]. The downside of the direct methods, however, has been the labor and cost-intensiveness, limiting their application to only local small and high-value areas including parks, city limits, orchards, and nurseries [

146,

147]. It may be possible to remove large areas of mistletoe-infested trees; however, scheduling this around the growth periods of various hosts would be difficult and time-consuming [

148,

149]. Additionally, there are many modes of seed dispersal, including birds, winds, and storms, which make these strategies difficult. For example, it is difficult to expect a dwarf mistletoe-free stand within approximately a hundred feet of an infected Ponderosa pine [

90,

150,

151,

152]. Reid and Yan [

153] highlighted the possibilities of developing aerial, ultra-light, surgical, and/or chemical delivery options. In either case, such approaches may not efficiently eliminate mistletoes from heavily parasitized trees [

153]. Surgical methods require time, labor, and financial costs, making them impracticable for small- to large-scale plantations [

29]. Owing to expenses, farmers inevitably cannot employ professional services from arborists and tree surgeons who offer tree lopping and pruning options [

29]. For them, the only option is to resort to the age-old traditions of pollarding, as in Southeast Australia [

29]. This, in addition to mistletoe control, gives them fodder during droughts, shade for livestock, firewood, and fencing [

29]. Other physical methods, such as the use of paints and deliberate fires, are viable measures [

154]. Fire applications have offered some appreciable control of the mistletoe population in the western USA forests [

155,

156,

157], because of mistletoes’ slow recovery rate compared to host(s) [

158,

159,

160]. However, the use of fire may have limitations in that a weakened host may favor mistletoe regrowth [

51,

161,

162]. Moreover, on holistic grounds, fire applications may raise public and environmental health concerns [

163,

164]. Indirect methods use irrigation, fertilization, brush and weed control, and regulating human disturbances [

29,

90,

165]. Irrigation profiles of the host may variously impact hemiparasite infectivity. In many cases, the higher water status of the host corroborates with heightened mistletoe infectivity, hinting that intermittent drought regimes would offer some protection for the hosts [

90,

166,

167,

168]. Improving the fertility of hosts by the use of nitrogen fertilizers has shown some protection from the mistletoes’ effects, with increments in tree height [

169]. Other indirect approaches also aid in improving host vigor and thus can be applied in large settings [

90]. Above all, scientific evaluation of the above strategies requires surplus funds and support for research and development communities to devise containment facilities and flexibilities in regulations to work in protected forest areas [

29].

1.2. Chemical Methods

Though with only limited prospects, chemical-agent-based approaches to mistletoe control have been more prevalent in various non-European countries such as India, Bangladesh [

57,

170], Australia [

171], and the United States [

88]. These methods involve the use of sprays or trunk injections of certain herbicide formulations to selectively control the hemiparasite without negatively impacting the host plant species [

171,

172,

173,

174]. In Eastern Australian farm eucalypts, the use of 2,4-D formulations had been investigated long ago in the 1950s and 1960s to control box mistletoes (

Ameyema spp.) [

174]. Besides their poor control, the trials could not be widely extended or reproduced with equivalent success due to the difficulties in ascertaining the optimum dose as influenced by various factors such as mistletoe host species, its size, the season of injection, the frequency of mistletoe infestation, and others [

171,

172,

173]. Formulations such as 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T, 2,4-MCPB, and dichloroethane have substantially been utilized to destroy

Viscum album subsp.

abietis on Abies with only insignificant host effects [

34]. However, complete resistance to mistletoe is never induced in hosts, as seen in the case of using 2,4-D and glyphosate, wherein mistletoe control only lasts half a year post-treatment [

34,

175]. A more promising herbicide control measure, according to a large study by Quick [

176], involves using an iso-octyl ester of 2,4,5-T, which was later banned for its non-target effects [

34]. It was shown that numerous other formulations tested between 1970 and the mid-1990s, such as Nutyrac, Dacamine, Thistrol, MCPA, Goal, D-40, Emulsamine, DPX, Prime, and Weedone, were unreactive to the endophytic system, despite killing mistletoe foliage exclusively, without adverse effects on the host [

128]. Similarly, ethephon (Florel, 2-Chloroethyl phosphoric acid), which releases ethylene, a plant growth regulator, has been tested with various dwarf mistletoe–host models in Manitoba, California, Idaho, New Mexico, Oregon, and Minnesota [

177,

178,

179]. With few non-target effects, it results in defoliation in mistletoe, albeit without influencing the haustorial connection, meaning that the complete evasion of infection is still a concern and recurrence cannot be ruled out [

180]. A defoliated but active haustorium can persist for over a century [

87].

It is still necessary to ensure the prompt delivery and adequate coverage of chemical agents, even if they appear potent enough [

26,

34,

181]. Ground applications can be effective but may not reach the hemiparasites in the tree overstory higher up in the canopies [

34]. Helicopter-based aerial delivery approaches, however, are challenged by poor penetration to the lower crowns, as sprays would be hindered by the overstory crowns [

182,

183]. To continue, chemical control methods pose many difficulties, such as limited technologies for the selective treatment of mistletoe over hosts, chemical damage to hosts, unavoidable reinfestation due to parasite seed germination or spread after chemical application, developing crops with a high tolerance to chemical applications, low penetration, persistence, availability, and so on [

180,

184]. Again, chemical agents that do not harm the haustorial connections may gradually exhibit resprouting [

185]. This will be graver in areas with greater incidences of mistletoe infection and its resprouting-led intensification [

185]. Despite the best chemical agents, mistletoe seeds will only be delayed for 2–4 years, so there is only a temporary solution to the problem [

34]. Considering these factors, alternative control and management methods are highly sought after.

1.3. Silvicultural Practices

In contrast to the above approaches, silvicultural practices have been more promising [

90,

128,

148]. These work by first clearing mistletoes from infection sites and then reintroducing a fresh lot of plants to the area [

186]. Such methods have been implemented for controlling dwarf mistletoes in North America [

128,

186]. Robinson and colleagues proposed a spatial–statistical model that simulates mistletoe growth and development under many control methods and offers a more preferable option [

187].

In small recreational and commercial settings, a silvicultural approach focuses on multiple factors, including ecological disturbances, harvests, prescribed fires, and need analysis and impact assessments [

148,

186]. They have gained acceptance as a routine strategy for highly devastating mistletoe and have slowed the development of resistant cultivars [

34]. Silvicultural practices, however, may not guarantee long-term and consistent efficacies due to the gradual changes in climate and shifts in devastating mistletoes related to their enhanced tropism [

186]. In order to scale this approach and ensure its success, newer options are highly desirable. A recent investigation showed an associational resistance to the spread of

Viscum album ssp.

austriacum in Northern Spain and indicated that mixed plantations of hosts (Scot pine,

Pinus sylvestris) with non-host (Maritime pine,

P. pinaster) trees greatly reduce mistletoe infestation [

188].

2. Mistletoe Control through Biotechnological Interventions and Smart Management

2.1. Mistletoe Biocontrol Agents (MBCAs)

Organisms with specific nutritional requirements that jeopardize their concomitant host(s), have emerged as a biocontrol strategy in most pest management routines [

24,

192,

193]. Integrated pest management practices have become an established part of agriculture, forestry, and horticulture [

194]. Such biocontrol agents offer wide acceptability and ease of application due to their straightforward and easy production processes and various biosafety and eco-friendly attributes [

195]. In particular, for use as MBCAs against dwarf mistletoes, various fungi, bacteria, and insects have been proposed [

196,

197,

198,

199,

200].

2.2. Requirements of an Effective MBCA Selection Program

A comprehensive investigation of MBCAs may require expansive sampling and surveys towards generating metadata on biological entities, viz., insects and microbial communities that selectively impose pathogenic symptoms on mistletoes without harming their respective tree hosts. Future research should focus on individual entities and on characterizing the performance of emerging MBCAs against specific mistletoes. There is a need for rigorous research on the synergistic effects of two or more potential species (which could create an MBCA cocktail) for more notorious mistletoe(s), areas complexed with more than one variety, or for those that attack multiple hosts at the same time. Examples of primitive studies of this type exist [

253,

254]. Insects have equal potential as microbes for use as MBCAs, as many in their larval form feed exclusively on mistletoes [

230]. In terms of MBCA potential, mistletoe pathogenicity alone cannot provide a concrete solution. Before selecting MBCAs, a checklist of features that best suit the testing of putative entities should be developed. An ideal checklist should include all the possible critical attributes on which MBCA hyperparasitism can be tested on acid, with a scoring system for their efficacy inherently (as MBCA) and their impact on the mistletoe, its tree host, and other non-host plantations. MBCAs would also require mass production, effective delivery systems, deployment strategies [

34], and a consistent monitoring program. Below is a comprehensive checklist of parameters that can be used to test and screen MBCA candidates (

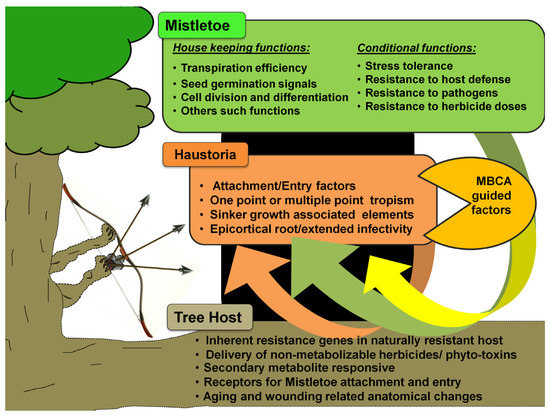

Figure 3).

Figure 3. Selective traits for testing and screening of potential MBCAs. The infographic depicts a generalized checklist of features desirable for testing and screening of putative MBCAs. A more detailed checklist should include features sought for MBCA formulations of specific organismic entities, viz., microbes, insects, etc. Some features in the above are adapted from known monographs [

216,

255].

2.3. Challenges with MBCAs

A different perspective considers pathogenic microbes and insects as co-evolving complex relationships with mistletoe hosts [

34]. Mistletoe outbreaks are induced or regulated by a variety of factors associated with seasonal and weather variations and their influences on multitrophic communities [

34]. This emphasizes the importance of intensive surveying, isolation, and study of the mistletoe–host specificity for each of the biological entities carrying considerable potential as an MBCA. Perhaps many microbes may appear circumstantially sensitive even to minute changes in their growth parameters [

256,

257]. The culturability and preservation (and conservation) of such organisms is also very important for reproducibility in continued/extended studies and applications. Many of these might be new, yet unexplored, rare, or others nearing extinction regarding strains, varieties, species, and of course their MBCA attributes. Moreover, some of these putative MBCAs may be lost due to environmental calamities and/or seasonal variations, especially for those very specific to the endemic mistletoes (especially their varieties). This must hold for entities that have no alternate host(s) than mistletoes. Examples of this could be the fruitfly genus,

Ceratitella, represented by only four species, all of which thrive exclusively on mistletoes [

258], or moths such as

Zelleria loranthivora (

Supplementary Table S1). Potential MBCAs are rare due to the scarcity of hosts that would otherwise enable their ecological expansion on more than one or very few mistletoe species. This seems imperative, especially for those endemic to not-so-vast geographic areas, where MBCA entities might lose some of their importance and worthiness if physical and chemical treatments are practiced in these areas. This will be more serious for entities that are closely related to, dependent on, or paralleled with mistletoe hosts. Mushtaque and Baloch’s study, for example, could not test six of the twelve insect species for MBCA potential [

231]. The conservation and production of rare isolates may represent new technical challenges, such as strain- or species-specific media compositions, microbial culturing, and insect-rearing protocols. In addition, selecting MBCAs would pose the challenge of competing with other members of the host–mistletoe microbiome, as has been highlighted recently [

259].

2.4. Inducing Host Plant Resistance to Mistletoes and/or Herbicides

Inherent resistance to mistletoes in some trees, such as Chinese pistachio (

Pistacia chinensis), crape myrtle (

Lagerstroemia), sycamore (

Platanus occidentalis), and conifers such as cedars (

Cedrus) and redwood (

Sequoioideae), has been documented amongst their susceptible genotypes [

260]. A call to develop a controlled breeding program catering to the identification of genetic bases for inherent resistance in tree hosts to hemiparasitic mistletoes was made as early as the 1960s [

189]. Due to the advent of cost-effective and convenient silviculture solutions, it has received little attention from the scientific community [

128]. Understanding the interactions of host–mistletoe compatibility would allow the selection of resistant varieties. Conventional breeding strategies, nevertheless, have developed some stably resistant tree lines [

261]. Tree hosts may be evaluated for resistance to herbicides, which may aid in the better application of chemical control approaches following herbicide translocation through such trees to their mistletoe parasite(s). For many tree crops, breeding programs are time-consuming, labor-intensive, require extensive field trials, and have not resulted in herbicide-resistant cultivars [

262]. Moreover, the chemical treatment of mistletoes on herbicide-resistant tree hosts might lead to the emergence of herbicide-tolerant mistletoes.

2.5. Hunting for the Genetic Basis to Hosts’ Inherent Resistance to Mistletoes: Background Studies

Because mistletoes have been co-evolving with their tree hosts for nearly 25 million years [

263], the emergence of inherent resistance in these hosts cannot be denied [

264], especially for the very native and devastating mistletoes [

265,

266]. A genetically directed effect is also implied by the fact that mistletoes exhibit specificity to their concomitant hosts, as well as variability in host preferences [

36,

64,

165,

247,

267,

268,

269,

270,

271,

272,

273,

274,

275,

276]. For example,

Arceuthobium douglasii does not parasitize

Pinus ponderosa [

128]; around 70% of dwarf mistletoe species with a principal host also pathogenize other hosts and still with variable levels of symptoms [

191]; and

A. pusillum fluctuates in terms of infection extent when exposed to

Larix laricina,

Picea glauca, P. rubens, and

Pinus strobes [

277]. On the contrary, there are also reported instances where mistletoes, in a heavily infected area, skipped infecting their principal host. A few observations were reviewed previously for

Arceuthobium spp. [

34] and one for

Dendrophthoe falcata more recently [

36]. However, studies are yet to present convincing demarcating features of preferred and not-so-preferred host type(s). These reports suggest existing variations in exhibiting resistance within the host population, even though the progeny of these trees have not been tested for resistance (a hotspot for further investigation). It is evident from these findings that few data are available regarding species-specific susceptibilities, which calls for rigorous field examinations such as progeny testing. Grafting techniques with putative resistant tree hosts used the inoculation of grafts and/or out-planting in mistletoe-infected sites [

265,

278]. Based on these trials, it appears that resistance is genetic rather than environmental. However, the heritability of this genetic regulation could not be documented. Many progeny tests to elucidate the heritability initially met with mixed results, with some escape or non-inheritable events [

128,

279,

280,

281]. Positives incidences [

265,

266,

282,

283] and later isozyme data from Nowicki’s work (as reviewed in Shamoun and DeWald [

34]) more strongly support heritability.

2.6. Mistletoe Community Restructuring, Disturbances, and Biological Interactions

Mistletoe infestations drastically differ at various geographic locations, and as such from urban to forest settings [

275,

284,

285,

286,

287]. Their prevalence in these areas can be variously influenced by the occurrence of host species [

276], host specificity [

275,

285], the behavior of dispersing agents [

79], pollinators [

288], habitat disturbances [

154,

289], herbivory [

138], and chemical interactions with the hosts [

290,

291]. Mistletoes may be differentially prevalent and infective from one to another host and within a population(s) of hosts [

292,

293]. Generalist mistletoes have a broad host range, while specialists exhibit host preferences [

64,

109,

275,

294]. Moreover, community dynamics profoundly impact parasite–host relationships [

79,

80,

108,

269,

270,

295]. Numerous life forms interact directly or indirectly with mistletoe, exhibiting either generalist or specialist behavior in doing so [

40,

79,

80,

81,

83,

84,

296,

297,

298]. Thus, field surveyors must consider influences under various circumstances before taking into account mistletoes’ infectivity, host preferences, and inherent resistance in the hosts within a particular geographical area (especially dense forest settings and commercial tree plantations). Vegetation disturbances such as the incidences of dead trees, grazing, logging, forest fires, and human waste disposal, among many others, may both positively and negatively affect mistletoe prevalence [

50,

299,

300,

301,

302]. Other than these, mistletoes may differ in their ability to readily establish seedling growth and mature persistently on various hosts [

273,

303,

304]. Mistletoes such as

Psittacathus calyculatus, Dendrophthoe falcata, and

Phoradendron californicum associate readily with leguminous tree hosts [

37,

39,

305]. Mistletoes’ diversity and evolution may be effectuated by host shifts, followed by host specialization, as well as variations in climate and environment [

306]. In addition to these factors, mistletoes’ success as parasites also depends on their complex interactions with herbivores, pollinators, and seed dispersers, such as birds, insects, and bats [

40,

41,

298,

307,

308,

309,

310]. Many also believe that the genetic structuring and isolation of mistletoe into populations growing on various hosts within a community is attributed to these avian gene dispersal vectors [

41,

42,

311]. However, based on the notion that most of these agents are insufficiently specialized, some believe that mistletoe speciation is mainly driven by host–parasite interplay [

274,

296,

297,

306,

312,

313,

314]. Inconsistencies in mistletoe frequency within host populations are primarily due to seed dispersal mechanisms and disperser behavior. Some mistletoes (such as

Arceuthobium spp.) exhibit explosive or ballistic seed dispersal [

83]. Bird-dispersed mistletoes generally show a patchy distribution, which is attributable to birds’ eating, roosting, and nesting behaviors [

39,

54,

315,

316,

317]. Forests with endemic marsupial seed dispersers may hold a similar analogy for effects on mistletoe prevalence and distributions [

296,

318,

319,

320]. Many host factors, such as tree diversity [

86,

273], height, crown width [

43,

49,

295,

321,

322,

323], and bark type [

267], as well as the recently studied stand characteristics [

105], regulate mistletoes’ colonization and density. These factors may also variously influence seed disperser behaviors. For example, the Sonoran desert mistletoe (

Phoradendron californicum) seeds are reported to be less frequently deposited on host tree species

Cercidium microphyllum and

Acacia constricta [

305]. The dense, thorny, and entangling crowns in these trees probably do not facilitate the perching behavior of avian dispersers [

305]. Additionally, competition among the host trees may reduce resource availability and negatively impact mistletoe infection and occurrence [

78]. Hosts may influence the reproductive phenology of their mistletoe parasites [

324]. This could be indirectly orchestrated by host-mediated influences over the pollinator communities with distinct pollinator rewards and those over mistletoes with pollen receipts, as well as avian visitations from distinct taxa on distinct hosts [

325,

326].

2.7. Transcriptomic/Metabolomic Profiling, Transgenic Trees, and Translational Research Pipeline

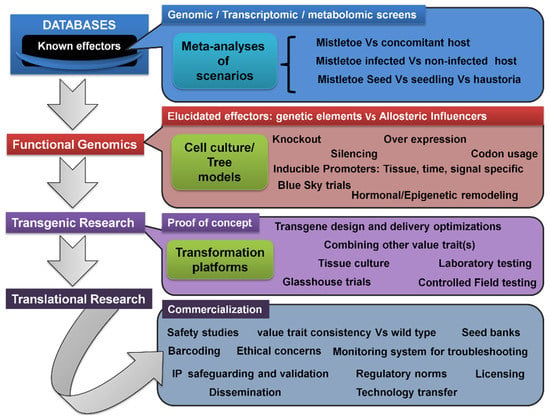

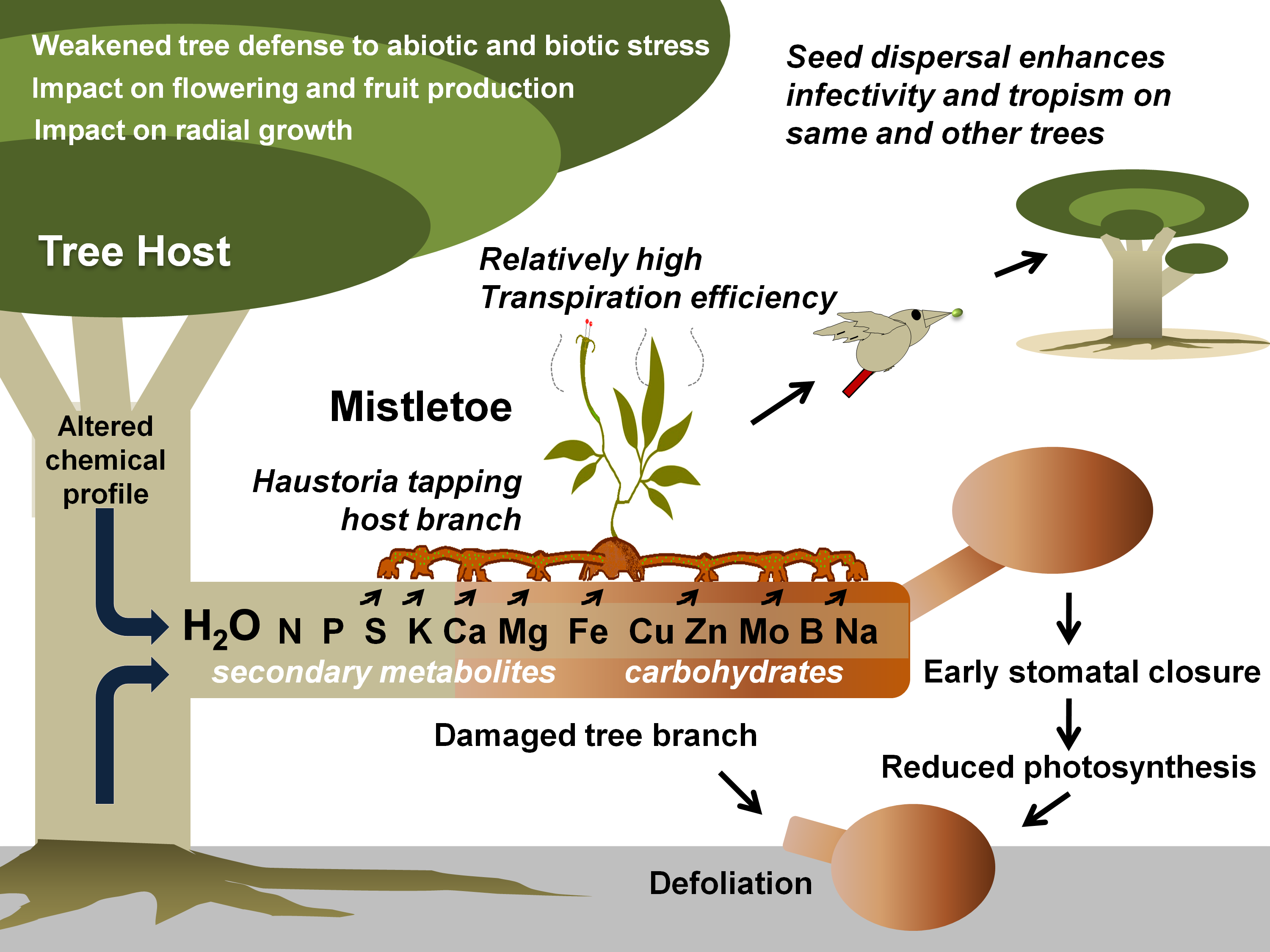

The genetic modification of mistletoe hosts to induce resistance, resulting in a new variety, could be a promising strategy for reducing damage [

335]. This would require the development of screening programs to characterize the viable sources of host resistance to each of the mistletoes (

Figure 4). Such screens can be examined for molecular DNA tags, aiding in expedited marker-assisted selection for mistletoe-resistant hosts. Nonetheless, limited but considerable progress has been made in this direction [

34,

336,

337,

338,

339]. Metabolomic profiling in other parasitic plants indicated the upregulation of auxin-responsive genes at the host–parasite interface [

340,

341]. Ichihashi’s group recently carried out both transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling of haustoria in the root hemiparasite

Thesium chinense, revealing upregulated transcripts for genes involved in the biosynthesis and signaling of very long-chain fatty acids, auxin, and lateral rhizogenesis [

342]. Along similar lines, Wang’s group attempted tissue-specific transcriptomics and whole-genome expression profiling of the shoot, flower, fruit, and seeds of spruce dwarf mistletoe (

Arceuthobium sichuanse), revealing 22,641 differentially expressed genes related majorly to photosynthesis, carbohydrate and cell metabolism, transcription, hormone biosynthesis, and their signaling [

343]. Recently, Wahid’s work extensively used tools such as suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) to report some 1279 genes in Ziarat junipers (

Juniperus excelsa) in Balochistan, which might putatively confer resistance to the dwarf mistletoe

Arceuthobium oxycedri [

344,

345]. Transcriptome profiling of

Taxillus nigrans individuals on four different tree hosts revealed many host-specific and common pathways driving this mistletoe’s parasitism [

346].

Figure 4. Resource-tapping possibilities from genetic pools to strategize transgenic host resistance to mistletoes. The gap in functional genomics studies on mistletoe parasitism has majorly limited the exogenous induction and/or introduction of mistletoe resistance in hosts. This would require, in principle, the characterization of genetic targets in mistletoe and tree hosts that signal and favor easy entry to mistletoes (shown here) and then testing of the conventional gene manipulation and transgenics’ frameworks (see Figure 5). Even putative MBCAs can be screened for genetic elements encoding factors detrimental to mistletoe parasitism and/or its life cycle.

Figure 5. Generalized transgenic and translational research pipeline for developing and disseminating stable mistletoe-resistant tree hosts of commercial value(s). Genetic elements (or their homologs) putatively conferring mistletoe resistance may be recovered from relevant repositories such as the NCBI’s GenBank and KEGG, and also may be screened using systems biology and bioinformatics tools, following genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic analyses. Some suggestions are depicted in Figure 4. Precisely, such meta-analyses can be performed on various pairs of genetic/expression pools. Once the genetic elements directly encoding the resistance trait or indirectly influencing the parasitism are stipulated, they may be tested on various grounds in small-scale assays and observations, in order to plan the appropriate design of the transgenic framework. In this way, cell and tissue culture models of parasitism involving trees and mistletoes may be indispensable and may generate proof(s) of concept(s). Then, a focused transgenic gene manipulation and characterization stage would involve lab-to-field-scale testing and validation of the successfully developed events. Translational activities would follow commercialization requisites on a case-by-case basis.

Research into transgenics would require a greater understanding of mistletoe’s genetics and molecular basis, as well as the dynamics and kinetics of materials’ flow between the host and its parasite (

Figure 4). Alternatively, where the same mistletoe parasitizes multiple hosts, it might be interesting to identify similar genetic and/or molecular elements, their influences, and their interactions within these frameworks. In addition, a comprehensive comparison of meta-analyses arising from infection instances between the same host and different parasite pairs could provide insight into rigidities, flexibilities, crucial events, genetic elements, and/or their encoded influences within these frameworks. These characterizations may lead to the development and testing of transgenic host(s) that are resistant to mistletoe attacks, but also produce fruit and timber in a qualitative and quantitative manner. Technically speaking, genetic engineering is endowed with certain choices of gene knockout and gene silencing options. In addition to site-directed mutagenesis, RNA antisense, small interfering RNA (si-RNA), and the CRISPR-Cas9 approaches, there are time-tested ways to manipulate transcription factors [

347,

348,

349,

350,

351]. The use of transgenic tree crops for translational research (

Figure 5) would revolutionize and open new avenues for commercial fruit and timber businesses worldwide, eliminating the need for the cost-, time-, and labor-intensive management of mistletoe pests, and potentially ending primitive conventional methods that are not eco-friendly. Other than this, transgenic approaches may be combined with chemical control options. This may be realized by developing hosts that can withstand the otherwise mistletoe-intolerable levels of herbicides while delivering them to deter mistletoe hemiparasites. In this arena, we believe that much of the background work has already been done, as in

Oronache and

Striga [

262,

352], and can also be seen in the launch of a transcriptome meta-analysis initiative, the Parasitic Plant Genome Project [

353]. There are a variety of reports that offer foundational studies on tree functional genomics [

354,

355,

356,

357,

358,

359]. As highlighted before, biotechnological approaches such as genetic engineering and plant tissue culture [

211,

360] have been underutilized, which indeed could represent a step away from conventional breeding strategies. There are few examples where tree transformation has been attempted in this regard. This should be seen as a critical requirement for introducing the usefully valued trait into specific fruit and timber tree cultivars [

361]. In mitigating the mistletoes, however, such initiatives are yet to see fruitful realization and technology translations.

2.8. Role of Epigenetic Signaling in Mistletoe Parasitism: Moving beyond the Genetic Basis

It is also important for scientists to determine how mistletoe parasitism is epigenetically modulated or influenced. Mistletoes exhibit epigenetic influences in their foliar appearance, mimicking their hosts [

362]. We have previously reported the unusual behavior of the loranth

Dendrophthoe falcata var.

falcata, exhibiting two different haustorial types on different fruit tree hosts [

36]. Moreover, in areas where more probable and notable hosts were present, only a few uncommon hosts succumbed to infection by

D. falcata [

36]. Why was this so? It would be imperative to test whether the epicortical roots emerging from

D. falcata from one host can attach to a different or the same host in proximity. In a similar manner, some of the other basic questions that are intriguing in this context may be as follows: What signals enable mistletoe seeds to germinate on existing hosts? How do mistletoes expand their host tropism in light of the ever-increasing list of newer hosts? Answers to these questions would offer more useful and efficient strategies to control mistletoes. One such strategy could consider manipulating plant signaling by transgenic and epigenetic interventions, and these may easily be integrated into pest management plans such as silviculture. Both mistletoes (for infection) and their host(s) (for defense) inflict changes in in each other’s physiological and chemical profiles [

53,

86]. There is still uncertainty as to whether mistletoe–host interactions involve any chemical warning signals analogous to the aposematism seen in other parasites [

363]. On the mistletoe’s end, some investigative leads have been gained; for example, the gelatinous seed coat material in

Phoradendron spp., viscin, is known to signal host/non-host responses [

87,

88]. Furthermore, to initiate attachment with the host, the mistletoes require seed germination stimulants (such as ethylene and nucleophilic protein receptor) and a diversity of haustoria-inducing factors (HIFs) [

275,

364]. HIFs such as xyloglucan endotransgycosylases (XETs), expansins, glucanases, and cell wall hydrolases are expressed in mistletoes [

89]. XETs may facilitate haustorial progression into hosts by delinking xyloglucans, which make up the secondary walls in the host vasculature [

365,

366]. Other HIFs comprise strigolactones, quinones, and flavonoids [

275,

367,

368,

369]. Oxidative degradation of host cell wall lignin by the action of peroxidases and H

2O

2 may also activate HIFs [

370]. The defense signals to mistletoes from the host side are analogous to that against herbivores and other biotic stressors [

9,

108,

371,

372,

373]. These are marked by anatomical variations such as lignification, suberization [

116,

374,

375], and the formation of secondary growth-like wound periderm [

292,

376], all of which variously oppose progression processes from mistletoes [

116]. In addition, hosts respond to mistletoe attack by making inherent changes to their hormone profiles, such as abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and indole-6-aminoacid [

374]. This may increase levels of potent secondary metabolites such as tannins, terpenes, and phenolic compounds [

9,

61,

109,

130,

332,

372,

373]. Furthermore, the infection site may display the accumulation of volatile compounds and ROS, in turn triggering enzyme cascades that signal for apoptosis, culminating in defoliation [

61,

130,

374]. The signaling crosstalk involved during the mistletoe life cycle over a host should therefore be examined for potential candidates that drive the epigenetic control over chemical dynamics. It is also likely that a precise understanding of the epigenetic framework that governs mistletoe–insect interactions may facilitate easier and more effective screening for MBCAs.

2.9. Smart Mistletoe Management: How the 21st Century Can Mitigate the Mistletoe Problem

The literature resources do not majorly document any new developments with conventional mistletoe management approaches due to technical glitches or technological paucity. Recently, a group described a novel handheld tool, ‘Mistletoe Eradicator’, which simultaneously provides both mechanical pruning and chemical treatment [

377]. The 21st century offers a huge range of possibilities with advancements into big data, automation, artificial intelligence, and platforms such as the Internet of Things (IoTs). Newer technologies such as artificial intelligence, satellite imaging (remote sensing), image recognition, drones, and weather forecasting can be utilized in substantiating smart solutions for mistletoe pest management programs.

For example, intelligent drones may permit the aerial screening of forest canopies for mistletoes, as well as for carrying out physical (pruning) and chemical treatments (herbicide spraying, branch injections, etc.). To make this For example, intelligent drones may permit the aerial screening of forest canopies for mistletoes, as well as for carrying out physical (pruning) and chemical treatments (herbicide spraying, branch injections, etc.). To make this possible, detection algorithms would need precision in screening and classifying mistletoes, which might face challenges resulting from the huge diversity of mistletoes, their growth stages, geographical settings, climates, canopy structures, size, density, etc. [86,378–383]. Moreover, many mistletoe species are known to mimic their hosts in foliar structures [139]. Moser and Campione showed the successful use of Google Earth as a remote sensing tool to detect eastern spruce dwarf mistletoe in the forests of Minnesota [384]. A group from Mexico recently developed a genetic programming-based algorithm that screens mistletoe possible, detection algorithms would need precision in screening and classifying mistletoes, which might face challenges resulting from the huge diversity of mistletoes, their growth stages, geographical settings, climates, canopy structures, size, density, etc. [86,378–383]. Moreover, many mistletoe species are known to mimic their hosts in foliar structures [139]. Moser and Campione showed the successful use of Google Earth as a remote sensing tool to detect eastern spruce dwarf mistletoe in the forests of Minnesota [384]. A group from Mexico recently developed a genetic programming-based algorithm that screens mistletoe Phoradendron velutinum using multispectral aerial images collected on a radiation sensor fitted to an unmanned aerial vehicle [385]. This algorithm classifies P. velutinum based on its flowering stage. Before this, several groups had developed other algorithms based on thermal imaging, hyperspectral lines, convolutional neural networks, canopy height, colorimetry, etc. [386–392]. If developments into these dimensions are studied further, the effective selection of conventional and biotechnological treatment approaches may lead to a productive synchrony with silviculture. Silvicultural decisions such as treatment area and treatment schedule depend on precise knowledge of and attention to the epidemiology of mistletoes and their pathogens, mistletoe population dynamics, and the silvics of the mistletoes’ hosts [34]. In this regard, even automation and artificial intelligence solutions may offer better time-saving, labor-saving, and cost-saving prospects, as well as being amenable to modifications on a case-by-case basis.

Considering the aforementioned promising approaches, and not neglecting the ecological value of the mistletoes (in being a keystone resource for biodiversity), the genetic engineering of hosts to develop, induce, and enhance specific resistance will be greatly rewarding. Even though its benefits include being environmentally safe and with no use of chemical agents, due to the additional labor, costs, complicated management, as well as potential to wipe out the parasite seed banks on hosts, this approach has remained unrealized [262]. Such transgenic trees would satisfy both (i) the conservation of the biodiversity and medicinal value aspects of mistletoes and (ii) aims to foresee a fruit and timber business that is unaffected by mistletoe. Successful examples of the transgenic approach are known in relation to other parasitic weeds, such as Striga, Orobanche, and Cuscuta . In this regard, in this study, we intended to supply blueprints for transgenic and translational research into developing and commercializing stable mistletoe-resistant tree cultivars.

In this review, the authors do not underestimate the ecological significance and medicinal value of mistletoes, both in traditional and modern treatment practices. However, this article emphasizes the development and implementation of more feasible management solutions for highly damaging mistletoes that affect commercial tree plantations. The risks surely outweigh the usefulness of mistletoes in such settings, as others pointed out long ago [230]. Thus, tree decline, combined with mistletoe, cannot be overlooked in itself as a major factor negatively impacting biodiversity and commerce. Hopefully, the biotechnological and smart management approaches discussed here, if operationalized in the future, should serve as a paradigm shift in mistletoe management.

For more details and complete reference list, please see the original article on MDPI-Biology at https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/11/11/1645

Please cite the authors as follows:

Mudgal, G.; Kaur, J.; Chand, K.; Parashar, M.; Dhar, S.K.; Singh, G.B.; Gururani, M.A. Mitigating the Mistletoe Menace: Biotechnological and Smart Management Approaches. Biology 2022, 11, 1645. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11111645

l, viscin, over the seed coat ensures firm attachment to the host branch (in 1) [87,88]. Hypocotyl(s) from the seed then emerges and grows towards the bark (in 2), which eventually, while attaching to the bark (in 3), penetrates through it (in 4) [89]. Once the hypocotyl connects to the host xylem (in 5), it exploits the host for water, minerals, carbohydrates, and secondary metabolites (in 6) [83]. The endophytic system may expand as sinkers (or epicortical roots) along the host cambium, from which sporadically new shoots may emerge (in 7) and facilitate the heightening of infectivity [65].

l, viscin, over the seed coat ensures firm attachment to the host branch (in 1) [87,88]. Hypocotyl(s) from the seed then emerges and grows towards the bark (in 2), which eventually, while attaching to the bark (in 3), penetrates through it (in 4) [89]. Once the hypocotyl connects to the host xylem (in 5), it exploits the host for water, minerals, carbohydrates, and secondary metabolites (in 6) [83]. The endophytic system may expand as sinkers (or epicortical roots) along the host cambium, from which sporadically new shoots may emerge (in 7) and facilitate the heightening of infectivity [65].