The Mongol conquest of Khwarezmia (Persian: حمله مغول به خوارزم), or the Mongol invasion of Iran (Persia) (Persian: حمله مغول به ایران), from 1219 to 1221 marked the beginning of the Mongol conquest of the Islamic states. The Mongol expansion would ultimately culminate in the conquest of virtually all of Asia as well as parts of Eastern Europe, with the exception of Japan , the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, Siberia, and most of the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. According to the Persian historian Minhaj-i-Siraj, Genghis Khan sent the ruler of the Khwarazmian Empire, Muhammad II, a message seeking trade and greeted him as his neighbor: "I am master of the lands of the rising sun while you rule those of the setting sun. Let us conclude a firm treaty of friendship and peace", or he said "I am Khan of the lands of the rising sun while you are sultan of those of the setting sun: Let us conclude a firm agreement of friendship and peace." The Mongols' original unification of all "people in felt tents", unifying the nomadic tribes in Mongolia and then the Turkomans and other nomadic peoples, had come with relatively little bloodshed, and almost no material loss. The Mongol wars with the Jurchens was known to Muhammad II and he agreed to this peace treaty. War between the Mongols and the Khwarazmian Empire started less than a year later, when a Mongol caravan and its envoys were massacred in the Khwarazmian city of Otrar. In the ensuing war, lasting less than two years, the Khwarazmian dynasty was destroyed and the Khwarazmian Empire was conquered.

- حمله

- مغول

- minhaj-i-siraj

1. Origins of the Conflict

After the defeat of the Kara-Khitans, Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire gained a border with the Khwarezmid Empire, governed by Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad. The Shah had only recently taken some of the territory under his control, and he was also busy with a dispute with the Caliph An-Nasir. The Shah had refused to make the obligatory homage to the caliph as titular leader of Islam, and demanded recognition as Shah of his empire, without any of the usual bribes or pretenses. This alone had created problems for him along his southern border. It was at this junction the rapidly expanding Mongol Empire made contact.[1] Mongol historians are adamant that the great khan at that time had no intention of invading the Khwarezmid Empire, and was only interested in trade and even a potential alliance.[2]

The Shah was very suspicious of Genghis' desire for a trade agreement, and messages from the Shah's ambassador at Zhongdu (Beijing) in China described the savagery of the Mongols when they assaulted the city during their war with the Jin dynasty.[3] Of further interest is that the caliph of Baghdad had attempted to instigate a war between the Mongols and the Shah some years before the Mongol invasion actually occurred. This attempt at an alliance with Genghis Khan was made because of a dispute between Nasir and the Shah, but the Khan had no interest in alliance with any ruler who claimed ultimate authority, titular or not, and which marked the Caliphate for an extinction which would come from Genghis' grandson, Hulegu. At the time, this attempt by the Caliph involved the Shah's ongoing claim to be named sultan of Khwarezm, something that Nasir had no wish to grant, as the Shah refused to acknowledge his authority, however illusory such authority was. However, it is known that Genghis rejected the notion of war as he was engaged in war with the Jin dynasty and was gaining much wealth from trading with the Khwarezmid Empire.

Genghis then sent a 500-man caravan of Muslims to establish official trade ties with Khwarezmia. However Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarezmian city of Otrar, had the members of the caravan that came from Mongolia arrested, claiming that the caravan was a conspiracy against Khwarezmia. With the assent of Sultan Muhammad, he executed the entire caravan, and its goods were sold in Bukhara[4]. It seems unlikely, however, that any members of the trade delegation were spies. Nor does it seem likely that Genghis was trying to initiate a conflict with the Khwarezmid Empire with the caravan, considering he was making steady progress against a faltering Jin empire in northern China at that very moment.[2]

Genghis Khan then sent a second group of three ambassadors (one Muslim and two Mongols) to meet the shah himself and demand the caravan at Otrar be set free and the governor be handed over for punishment. The shah had both of the Mongols shaved and had the Muslim beheaded before sending them back to Genghis Khan. Muhammad also ordered the personnel of the caravan to be executed. This was seen as a grave affront to the Khan himself, who considered ambassadors "as sacred and inviolable".[5] This led Genghis Khan to attack the Khwarezmian dynasty. The Mongols crossed the Tian Shan mountains, coming into the Shah's empire in 1219.[6]

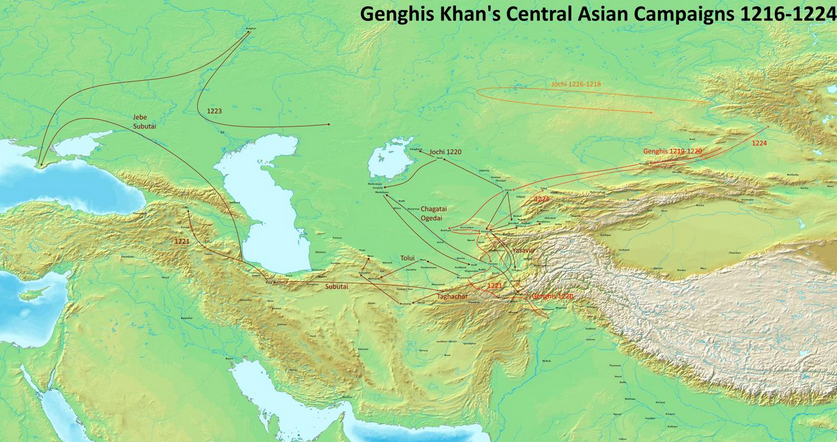

2. Planning and Dispositions

After compiling information from many intelligence sources, primarily from spies along the Silk Road, Genghis Khan carefully prepared his army, which was organized differently from his earlier campaigns.[7] The changes had come in adding supporting units to his dreaded cavalry, both heavy and light. While still relying on the traditional advantages of his mobile nomadic cavalry, Genghis incorporated many aspects of warfare from China, particularly in siege warfare. His baggage train included such siege equipment as battering rams, gunpowder, and enormous siege bows capable of throwing 20-foot (6 m) arrows into siege works. Also, the Mongol intelligence network was formidable. The Mongols never invaded an opponent whose military and economic will and ability to resist had not been thoroughly and completely scouted. For instance, Subutai and Batu Khan spent a year scouting central Europe, before destroying the armies of Hungary and Poland in two separate battles, two days apart.[8]

In this invasion, the Khan first demonstrated the use of indirect attack that would become a hallmark of his later campaigns, and those of his sons and grandsons. The Khan divided his armies, and sent one force solely to find and execute the Shah – so that he was forced to run for his life in his own country.[1] The divided Mongol forces destroyed the Shah's forces piecemeal, and began the utter devastation of the country which would mark many of their later conquests.

The Shah's army, numbering anywhere from 40,000 to 200,000 (mostly city garrisons), was split among the various major cities, bar an elite unit of cavalry stationed near Samarkand as a reserve force. The empire had just recently conquered much of its territory, and the Shah was fearful that his army, if placed in one large unit under a single command structure, might possibly be turned against him. Furthermore, the Shah's reports from China indicated that the Mongols were not experts in siege warfare, and experienced problems when attempting to take fortified positions. The Shah's decisions on troop deployment would prove disastrous as the campaign unfolded, as the Mongol speed, surprise, and enduring initiative prevented the Shah from effectively maneuvering his forces.

2.1. Forces

The estimates for the sizes of the opposing armies are often in dispute. It is certain that all contemporary and near-contemporary sources (or at least those that have survived), consider the Mongols to have been the numerically superior force.[9] Several chroniclers, a notable one being Rashid Al-Din (a historian of the Mongol Ilkhanate) provide the figures of 400,000 for the Shah (spread across the whole empire) and 600,000 or 700,000 for the Khan.[10] The contemporary Muslim chronicler Minhaj-i-Siraj Juzjani, in his Tarikh-i Jahangushay, also gives a Mongol army size of 700,000 to 800,000 for Genghis. Modern historians still debate to what degree these numbers reflected reality. David Morgan and Denis Sinor, among others, doubt the numbers are true in either absolute or relative terms, while John Mason Smith sees the numbers as accurate as for both armies (while supporting high-end numbers for the Mongols and their enemies in general, for instance contending that Rashid Al-Din was correct when stating that the Ilkhanate of the 1260s had 300,000 soldiers and the Golden Horde 300,000–600,000).[11] Sinor uses the figure of 400,000 for the Khwarezmians, but puts the Mongol force at 150,000. The Secret History of the Mongols, a Mongol source, states that the Mongols had 105,000 soldiers total (in the whole empire, not just on a campaign) in 1206, 134,500 in 1211, and 129,000 (excluding some far-flung units) in 1227. No similarly reliable source exists for corresponding Khwarezm figures.[12]

Carl Sverdrup, using a variety of sources and estimation methods, gives the number of 75,000 for the Mongol army. Sverdrup also estimates the Khwarezmian army at 40,000 (excluding certain city-restricted militias), and emphasizes that all contemporary sources are in agreement that, if nothing else, the Mongol army was the larger of the two. He states that he came to 40,000 by first calculating the size of the Mongol army based on their historical records, and then assuming the Kwharezmian army was exaggerated by the pro-Mongol historians such as Rashid Al-Din to about the same magnitude as the Mongol army was by both Rashid Al-Din and anti-Mongol chroniclers such as Juzjani.[13] McLynn also says that 400,000 is a massive exaggeration, but considers 200,000 to be closer to the truth (including garrisons).[14] As for the Mongols, he estimates them at 120,000 effectives, out of a total Mongol strength of 200,000 (including troops nominally on the campaign but never engaged, and those in China).[15] Genghis brought along his most able generals, besides Muqali to aid him. Genghis also brought a large body of foreigners with him, primarily of Chinese origin. These foreigners were siege experts, bridge-building experts, doctors and a variety of specialty soldiers.

The only hard evidence of the empire's potential military strength comes from a census ordered by Hulegu Khan of the same regions a few decades later. At that point Hulegu ruled almost all the lands of the former Khwarezmian empire including Persia, modern-day Turkmenistan, and Afghanistan, only missing most of modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and the region had had over 40 years to recover population-wise from the initial conquest. These lands were judged to be able to muster five tümens in all.[16] Nominally each tumen was supposed to consist of 10,000 men, but they usually averaged 5,000 men.[17] If Hulegu's census was accurate, then the bulk of the former Khwarezmian lands together could field 25,000 soldiers, lending credence to Sverdrup's estimate of 40,000 troops in total.

During the invasion of Transoxania in 1219, along with the main Mongol force, Genghis Khan used a Chinese specialist catapult unit in battle; they were used again in 1220 in Transoxania. The Chinese may have used the catapults to hurl gunpowder bombs, since they already had them by this time.[18] While Genghis Khan was conquering Transoxania and Persia, several Chinese who were familiar with gunpowder were serving with Genghis's army.[19] Historians have suggested that the Mongol invasion had brought Chinese gunpowder weapons to Central Asia. One of these was the huochong, a Chinese mortar.[20]

2.2. Khwarezmian Weakness and Disunity

In addition to quite possibly outnumbering the force of the Shah, and definitely possessing more horsemen in total and more men at almost every battle, the Mongols were benefited enormously by the fragility of the Khwarezmian empire. While often portrayed as a strong and unified state, most of the Shah's holdings were recent conquests only nominally sworn to him, to the point that the Shah didn't feel like he could trust most of his troops. In the words of historian C. E. Bosworth: "[The dynasty was] highly unpopular and a focus for popular hatred; in none of the provinces they ruled did the Khwarazm Shahs ever succeed in creating a bond of interest between themselves and their subjects."[21] This resulted in him parsing them in garrisons to be commanded by local governors that acted more or less autonomously. There was no attempt to coordinate a grand strategy among the various provinces or unite a significant number of forces in one unified front against the invaders.[22] Additionally, many of the areas that Muhammad charged his troops to defend had been devastated recently by the forces of the Shah himself. For example, in 1220 he passed through Nishapur and urged the citizens to repair the fortifications he had destroyed when conquering the city years earlier.[23]

The lack of unity in the empire often resulted in large sections of the Shah's army folding with little or no fighting when the Mongols arrived. According to Ibn al-Athir, when Bukhara was attacked most of the Khwarazmian army simply deserted and left the city, leaving the now poorly-defended settlement to seek terms.[24] When Samarkand was subsequently attacked, the Turkic soldiers in the city, who felt no loyalty towards the Shah, allegedly said of the Mongols: "We are their race. They will not kill us." They surrendered after only four days of fighting before turning the city over to the Mongols on the fifth. However they were executed along with much of the city's population regardless, much to their surprise.[25] Balkh's garrison surrendered without a fight. Merv's garrison surrendered after seven days and a few minor sorties (of only around a couple hundred men each, according to the pro-Mongol Juvayni); they were also all executed, again to their shock.[26] The only major cities known to put up a stout defense were Otrar, which managed to hold out for six months before being captured by the Mongols amidst heavy casualties and a large delay for the Mongol army, and Urgench, where Ibn al-Athir claimed that Mongol losses exceeded those of the defending soldiers for one of the only times in the war.[27][28] The unreliability of the Shah's army was probably most decisive when his son Jalal al-Din's cavalry host simply disintegrated due to desertion as his Afghan and Turkic allies disagreed with him over the distribution of war booty. His forces were reduced heavily which allowed the Mongols to easily overcome them at the Indus River.[29] The Mongols took full advantage of these circumstances with their network of spies, often aided by merchants who had much to gain from Mongol domination and spread rumors imploring the inhabitants of cities to surrender.[30]

2.3. Khwarezmian Structure

Another advantage for the Mongols was the fact that, compared to most of China, Korea, Central/Western Europe, and many other areas, Khwarezmia was deficient in terms of fortifications. In most of the empire there was no system of forts outside of the walls of major cities, and even the most important cities such as Samarkand and Otrar had their walls constructed out of mud bricks which could be easily reduced by Mongol siege engines.[31] This meant that the Mongols, rather than getting bogged down in dozens of small sieges or single multi-year ones as sometimes happened in China, could simply sweep through large areas of the empire and conquer cities at will in a short time. They had more difficulty in subduing Afghanistan, which had a fortress network, though the relative scarcity of fortresses in the whole of the empire and the ease with which the Mongols subdued large sections of it meant that this did not matter on a strategic scale. The fortress of Ashiyar held for 15 months of besiegement before falling (requiring the attention of a significant chunk of the Mongol army) while Saif-Rud and Tulak took heavy casualties for the Mongols to subdue. The siege of Bamyan also claimed the life of Chagatai's favorite son, Mötüken.[32]

The urban population of the empire was concentrated in a relatively small number of (by medieval standards) very large cities as opposed to a huge number of smaller towns, which also aided in the Mongols' conquest. The population of the empire is estimated at 5 million people on the eve of the invasion, making it sparse for the large area it covered.[33][34] Historical demographers Tertius Chandler and Gerald Fox give the following estimations for the populations of the empire's major cities at the beginning of the 13th century, which adds up to at least 520,000 and at most 850,000 people:[35]

- Samarkand: 80,000–100,000

- Nishapur: 70,000

- Rayy/Rey: 100,000

- Isfahan: 80,000

- Merv: 70,000

- Balkh: c. 30,000

- Bost: c. 40,000

- Herat: c. 40,000

- Otrar, Urgench, and Bukhara: unknown, but less than 70,000[36]

The Khwarezmian army consisted of about 40,000 cavalry, mostly of Turkic origin. Militias existed in Khwarezmia's major cities but were of poor quality, and the Shah had trouble mustering them in time.[37] With collective populations of around 700,000, the major cities probably had 105,000 to 140,000 healthy males of fighting age in total (15–20% of the population), but only a fraction of these would be part of a formal militia with any notable measure of training and equipment.

3. Initial Invasion

Though they technically bordered each other, the Mongol and Khwarezm Empires touched far away from the homeland of each nation. In between them was a series of treacherous mountain ranges that the invader would have to cross. This aspect is often overlooked in this campaign, yet it was a critical reason why the Mongols were able to create a dominating position. The Khwarezm Shah and his advisers assumed that the Mongols would invade through the Dzungarian Gate, the natural mountain pass in between their (now conquered) Khara-Khitai and Khwarezm Empires. One option for the Khwarezm defense was to advance beyond the towns of the Syr Darya and block the Dzungarian Gate with an army, since it would take Genghis many months to gather his army in Mongolia and advance through the pass after winter had passed. The Khwarezm decision makers believed they would have time to further refine their strategy, but the Khan had struck first.[38]

Immediately when war was declared, Genghis sent orders for a force already out to the west to immediately cross the Tien Shan mountains to the south and ravage the fertile Ferghana Valley in the eastern part of the Khwarezm Empire. This smaller detachment, no more than 20,000–30,000 men, was led by Genghis's son Jochi and his elite general Jebe. The Tien Shan mountain passes were much more treacherous than the Dzungarian Gate, and to make it worse, they attempted the crossing in the middle of winter with over 5 feet of snow. Though the Mongols suffered losses and were exhausted from the crossing, their presence in the Ferghana Valley stunned the Khwarezm leadership and permanently stole the initiative away. This march can be described as the Central Asian equivalent of Hannibal's crossing of the Alps, with the same devastating effects. Because the Shah did not know if this Mongol army was a diversion or their main army, he had to protect one of his most fertile regions with force. Therefore, the Shah dispatched his elite cavalry reserve, which prevented him from effectively marching anywhere else with his main army. Jebe and Jochi seem to have kept their army in good shape while plundering the valley, and they avoided defeat by a much superior force. At this point the Mongols split up and again maneuvered over the mountains: Jebe marched further south deeper into Khwarezm territory, while Jochi took most of the force northwest to attack the exposed cities on the Syr Darya from the east.[39]

3.1. Otrar

Meanwhile, another Mongol force under Chagatai and Ogedei descended from either the Altai Mountains to the north or the Dzungarian Gate and immediately started laying siege to the border city of Otrar. Rashid Al-Din stated that Otrar had a garrison of 20,000 while Juvayni claimed 60,000 (horsemen and militia), though like the army figures given in most medieval chronicles, these numbers should be treated with caution and are probably exaggerated by an order of magnitude considering the size of the city.[40] Genghis, who had marched through the Altai mountains, kept his main force further back near the mountain ranges, and stayed out of contact. Frank McLynn argues that this disposition can only be explained as Genghis laying a trap for the Shah. Because Shah decided to march his army up from Samarkand to attack the besiegers of Otrar, Genghis could then rapidly encircle the Shah's army from the rear. However, the Shah dodged the trap, and Genghis had to change plans.[41]

Unlike most of the other cities, Otrar did not surrender after little fighting, nor did its governor march its army out into the field to be destroyed by the numerically superior Mongols. Instead the garrison remained on the walls and resisted stubbornly, holding out against many attacks. The siege proceeded for five months without results, until a traitor within the walls (Qaracha) who felt no loyalty to the Shah or Inalchuq opened the gates to the Mongols; the prince's forces managed to storm the now unsecured gate and slaughter the majority of the garrison.[42] The citadel, holding the remaining one-tenth of the garrison, held out for another month, and was only taken after heavy Mongol casualties. Inalchuq held out until the end, even climbing to the top of the citadel in the last moments of the siege to throw down tiles at the oncoming Mongols and slay many of them in close quarters combat. Genghis killed many of the inhabitants, enslaved the rest, and executed Inalchuq.[43][44]

4. Sieges of Bukhara, Samarkand, and Urgench

At this point, the Mongol army was divided into five widely separated groups on opposite ends of the enemy Empire. After the Shah did not mount an active defense of the cities on the Syr Darya, Genghis and Tolui, at the head of an army of roughly 50,000 men, skirted the natural defense barrier of the Syr Darya and its fortified cities, and went westwards to lay siege to the city of Bukhara first. To do this, they traversed 300 miles of the seemingly impassable Kyzyl Kum desert by hopping through the various oases, guided most of the way by captured nomads. The Mongols arrived at the gates of Bukhara virtually unnoticed. Many military tacticians regard this surprise entrance to Bukhara as one of the most successful maneuvers in warfare.[45] Whatever Mohammed II was intending to do, Genghis's maneuver across his rear completely stole away his initiative and prevented him from carrying out any possible plans. The Khwarezm army could only slowly react to the lightning fast Mongol maneuvers.

4.1. Bukhara

Bukhara was not heavily fortified, with a moat and a single wall, and the citadel typical of Khwarezmi cities. The Bukharan garrison was made up of Turkic soldiers and led by Turkic generals, who attempted to break out on the third day of the siege. Rashid Al-Din and Ibn Al-Athir state that the city had 20,000 defenders, though Carl Sverdrup contends that it only had a tenth of this number.[46] A break-out force was annihilated in open battle. The city leaders opened the gates to the Mongols, though a unit of Turkic defenders held the city's citadel for another twelve days. The Mongols valued artisan skills highly and artisans were exempted from massacre during the conquests and instead entered into lifelong service as slaves.[47] Thus, when the citadel was taken survivors were executed with the exception of artisans and craftsmen, who were sent back to Mongolia. Young men who had not fought were drafted into the Mongolian army and the rest of the population was sent into slavery. As the Mongol soldiers looted the city, a fire broke out, razing most of the city to the ground.[48]

4.2. Samarkand

After the fall of Bukhara, Genghis headed to the Khwarezmian capital of Samarkand and arrived in March 1220. During this period, the Mongols also waged effective psychological warfare and caused divisions within their foe. The Khan's spies told them of the bitter fighting between the Shah and his mother, who commanded the allegiance of some of his most senior commanders and his elite Turkish cavalry divisions. Since Mongols and Turks are both steppe peoples, Genghis argued that Tertun Khatun and her army should join the Mongols against her treacherous son. Meanwhile, he arranged for deserters to bring letters that said Tertun Khatun and some of her generals had allied with the Mongols. This further inflamed the existing divisions in the Khwarezm Empire, and probably prevented the senior commanders from unifying their forces. Genghis then compounded the damage by repeatedly issuing bogus decrees in the name of either Tertun Khatun or Shah Mohammed, further tangling up the already divided Khwarezm command structure.[49] As a result of the Mongol strategic initiative, speedy maneuvers, and psychological strategies, all the Khwarezm generals, including the Queen Mother, kept their forces as a garrison and were defeated in turn.

Samarkand possessed significantly better fortifications and a larger garrison compared to Bukhara. Juvayni and Rashid Al-Din (both writing under Mongol auspices) credit the defenders of the city with 100,000–110,000 men, while Ibn Al-Athir states 50,000.[50] A more likely number is perhaps 10,000, considering the city itself had less than 100,000 people total at the time.[51][52] As Genghis began his siege, his sons Chaghatai and Ögedei joined him after finishing the reduction of Otrar, and the joint Mongol forces launched an assault on the city. The Mongols attacked using prisoners as body shields. On the third day of fighting, the Samarkand garrison launched a counterattack. Feigning retreat, Genghis drew approximately half of the garrison outside the fortifications of Samarkand and slaughtered them in open combat. Shah Muhammad attempted to relieve the city twice, but was driven back. On the fifth day, all but a handful of soldiers surrendered. The remaining soldiers, die-hard supporters of the Shah, held out in the citadel. After the fortress fell, Genghis reneged on his surrender terms and executed every soldier that had taken arms against him at Samarkand. The people of Samarkand were ordered to evacuate and assemble in a plain outside the city, where many were killed.

About the time of the fall of Samarkand, Genghis Khan charged Subutai and Jebe, two of the Khan's top generals, with hunting down the Shah. The Shah had fled west with some of his most loyal soldiers and his son, Jalal al-Din, to a small island in the Caspian Sea. It was there, in December 1220, that the Shah died. Most scholars attribute his death to pneumonia, but others cite the sudden shock of the loss of his empire.

4.3. Urgench

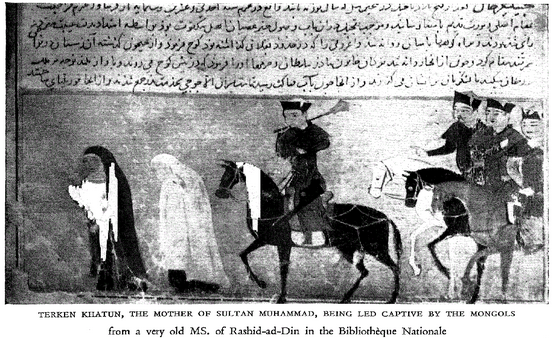

Meanwhile, the wealthy trading city of Urgench was still in the hands of Khwarezmian forces. Previously, the Shah's mother had ruled Urgench, but she fled when she learned her son had absconded to the Caspian Sea. She was captured and sent to Mongolia. Khumar Tegin, one of Muhammad's generals, declared himself Sultan of Urgench. Jochi, who had been on campaign in the north since the invasion, approached the city from that direction, while Genghis, Ögedei, and Chaghatai attacked from the south.

The assault on Urgench proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion. The city was built along the river Amu Darya in a marshy delta area. The soft ground did not lend itself to siege warfare, and there was a lack of large stones for the catapults. The Mongols attacked regardless, and the city fell only after the defenders put up a stout defense, fighting block for block. Mongolian casualties were higher than normal, due to the unaccustomed difficulty of adapting Mongolian tactics to city fighting.

The taking of Urgench was further complicated by continuing tensions between the Khan and his eldest son, Jochi, who had been promised the city as his prize. Jochi's mother was the same as his three brothers': Genghis Khan's teen bride, and apparent lifelong love, Börte. Only her sons were counted as Genghis's "official" sons and successors, rather than those conceived by the Khan's 500 or so other "wives and consorts". But Jochi had been conceived in controversy; in the early days of the Khan's rise to power, Börte was captured and raped while she was held prisoner. Jochi was born nine months later. While Genghis Khan chose to acknowledge him as his oldest son (primarily due to his love for Börte, whom he would have had to reject had he rejected her child), questions had always existed over Jochi's true parentage.[53]

Such tensions were present as Jochi engaged in negotiations with the defenders, trying to get them to surrender so that as much of the city as possible was undamaged. This angered Chaghatai, and Genghis headed off this sibling fight by appointing Ögedei the commander of the besieging forces as Urgench fell. But the removal of Jochi from command, and the sack of a city he considered promised to him, enraged him and estranged him from his father and brothers, and is credited with being a decisive impetus for the later actions of a man who saw his younger brothers promoted over him, despite his own considerable military skills.[1]

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar Juvayni states that 50,000 Mongol soldiers were given the task of executing twenty-four Urgench citizens each, which would mean that 1.2 million people were killed. While this is almost certainly an exaggeration, the sacking of Urgench is considered one of the bloodiest massacres in human history.

Then came the complete destruction of the city of Gurjang, south of the Aral Sea. Upon its surrender the Mongols broke the dams and flooded the city, then proceeded to execute the survivors.

5. The Khorasan Campaign

As the Mongols battered their way into Urgench, Genghis dispatched his youngest son Tolui, at the head of an army, into the western Khwarezmid province of Khorasan. Khorasan had already felt the strength of Mongol arms. Earlier in the war, the generals Jebe and Subutai had travelled through the province while hunting down the fleeing Shah. However, the region was far from subjugated, many major cities remained free of Mongol rule, and the region was rife with rebellion against the few Mongol forces present in the region, following rumors that the Shah's son Jalal al-Din was gathering an army to fight the Mongols.

5.1. Balkh

Tolui's army consisted of somewhere around 50,000 men, which was composed of a core of Mongol soldiers (some estimates place it at 7,000[54]), supplemented by a large body of foreign soldiers, such as Turks and previously conquered peoples in China and Mongolia. The army also included "3,000 machines flinging heavy incendiary arrows, 300 catapults, 700 mangonels to discharge pots filled with naphtha, 4,000 storming-ladders, and 2,500 sacks of earth for filling up moats".[5] Among the first cities to fall was Termez then Balkh.

5.2. Merv

The major city to fall to Tolui's army was the city of Merv. Juvayni wrote of Merv: "In extent of territory it excelled among the lands of Khorasan, and the bird of peace and security flew over its confines. The number of its chief men rivaled the drops of April rain, and its earth contended with the heavens."[54] The garrison at Merv was only about 12,000 men, and the city was inundated with refugees from eastern Khwarezmia. For six days, Tolui besieged the city, and on the seventh day, he assaulted the city. However, the garrison beat back the assault and launched their own counter-attack against the Mongols. The garrison force was similarly forced back into the city. The next day, the city's governor surrendered the city on Tolui's promise that the lives of the citizens would be spared. As soon as the city was handed over, however, Tolui slaughtered almost every person who surrendered, in a massacre possibly on a greater scale than that at Urgench.

5.3. Nishapur

After finishing off Merv, Tolui headed westwards, attacking the cities of Nishapur and Herat.[55] Nishapur fell after only three days; here, Tokuchar, a son-in-law of Genghis was killed in battle, and Tolui put to the sword to every living thing in the city, including the cats and dogs, with Tokuchar's widow presiding over the slaughter.[54] After Nishapur's fall, Herat surrendered without a fight and was spared.

Bamian in the Hindu Kush was another scene of carnage during the 1221 siege of Bamiyan, here stiff resistance resulted in the death of a grandson of Genghis. Next was the city of Toos. By spring 1221, the province of Khurasan was under complete Mongol rule. Leaving garrison forces behind him, Tolui headed back east to rejoin his father.

6. The Final Campaign and Aftermath

After the Mongol campaign in Khorasan, the Shah's army was broken. Jalal al-Din, who took power after his father's death, began assembling the remnants of the Khwarezmid army in the south, in the area of Afghanistan. Genghis had dispatched forces to hunt down the gathering army under Jalal al-Din, and the two sides met in the spring of 1221 at the town of Parwan. The engagement was a humiliating defeat for the Mongol forces. Enraged, Genghis headed south himself, and defeated Jalal al-Din on the Indus River. Jalal al-Din, defeated, fled to India. Genghis spent some time on the southern shore of the Indus searching for the new Shah, but failed to find him. The Khan returned northwards, content to leave the Shah in India.

After the remaining centers of resistance were destroyed, Genghis returned to Mongolia, leaving Mongolian garrison troops behind. The destruction and absorption of the Khwarezmid Empire would prove to be a sign of things to come for the Islamic world, as well as Eastern Europe.[48] The new territory proved to be an important stepping stone for Mongol armies under the reign of Genghis' son Ögedei to invade Kievan Rus' and Poland, and future campaigns brought Mongol arms to Hungary and the Baltic Sea. For the Islamic world, the destruction of Khwarezmia left Iraq, Turkey and Syria wide open. All three were eventually subjugated by future Khans.

The war with Khwarezmia also brought up the important question of succession. Genghis was not young when the war began, and he had four sons, all of whom were fierce warriors and each with their own loyal followers. Such sibling rivalry almost came to a head during the siege of Urgench, and Genghis was forced to rely on his third son, Ögedei, to finish the battle. Following the destruction of Urgench, Genghis officially selected Ögedei to be successor, as well as establishing that future Khans would come from direct descendants of previous rulers. Despite this establishment, the four sons would eventually come to blows, and those blows showed the instability of the Khanate that Genghis had created.

Jochi never forgave his father, and essentially withdrew from further Mongol wars, into the north, where he refused to come to his father when he was ordered to.[53] Indeed, at the time of his death, the Khan was contemplating a march on his rebellious son. The bitterness that came from this transmitted to Jochi's sons, and especially Batu and Berke Khan (of the Golden Horde), who would conquer Kievan Rus.[8] When the Mamluks of Egypt managed to inflict one of history's more significant defeats on the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, Hulagu Khan, one of Genghis Khan's grandsons by his son Tolui, who had sacked Baghdad in 1258, was unable to avenge that defeat when Berke Khan, his cousin, (who had converted to Islam) attacked him in the Transcaucasus to aid the cause of Islam, and Mongol battled Mongol for the first time. The seeds of that battle began in the war with Khwarezmia when their fathers struggled for supremacy.[48]

7. In Popular Culture

Mongol conquest of Khwarezmia is featured in the single-player campaign of the Age of Empires II video game, created by Ensemble Studios and published by Microsoft. In this video game, however, Mongols start their invasion by assassinating the Shah. The assassins disguise themselves as traders.

In the grand strategy video game Crusader Kings II the "Age of Mongols" book mark starts during the invasion.

References

- Saunders, J. J. The History of the Mongol Conquests

- Hildinger, Eric. Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1700

- Soucek, Svatopluk A History of Inner Asia

- Leo de Hartog (2004). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. Tauris Parke. pp. 86–87. ISBN 1-86064-972-6. https://archive.org/details/genghiskhanconqu00hart/page/86.

- Prawdin, Michael. The Mongol Empire.

- Ratchnevsky 1994, p. 129.

- See Mongol military tactics and organization for overall coverage.

- Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen

- France, p. 113

- Rashid Al-Din, "Compendium of Chronicles", 2:346.

- John Mason Smith, "Mongol Manpower and Persian Population", pp. 276, 272

- France, pp. 109–113

- France, pp. 113–114

- McLynn, F. (2015). Genghis Khan: His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy. Da Capo Press. Page 263.

- Ibid, p. 268

- Juyaini, p. 511, 518. Cited in John Mason Smith, "Mongol Manpower and Persian Population", Journal of the Economics and Social History of the Orient, Vol XVIII, Part III, page 278.

- France p. 113, citing David Morgan

- Kenneth Warren Chase (2003). Firearms: a global history to 1700 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-521-82274-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=esnWJkYRCJ4C&pg=PA58. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "Chinggis Khan organized a unit of Chinese catapult specialists in 1214, and these men formed part of the first Mongol army to invade Transoania in 1219. This was not too early for true firearms, and it was nearly two centuries after catapult-thrown gunpowder bombs had been added to the Chinese arsenal. Chinese siege equipment saw action in Transoxania in 1220 and in the north Caucasus in 1239–40."

- David Nicolle; Richard Hook (1998). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane (illustrated ed.). Brockhampton Press. p. 86. ISBN 1-86019-407-9. https://books.google.com/?id=OgQXAQAAIAAJ&q=Though+he+was+himself+a+Chinese,+he+learned+his+trade+from+his+father,+who+had+accompanied+Genghis+Khan+on+his+invasion+of+Muslim+Transoxania+and+Iran.+Perhaps+the+use+of+gunpowder+as+a+propellant,+in+other+words+the+invention+of+true&dq=Though+he+was+himself+a+Chinese,+he+learned+his+trade+from+his+father,+who+had+accompanied+Genghis+Khan+on+his+invasion+of+Muslim+Transoxania+and+Iran.+Perhaps+the+use+of+gunpowder+as+a+propellant,+in+other+words+the+invention+of+true. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "Though he was himself a Chinese, he learned his trade from his father, who had accompanied Genghis Khan on his invasion of Muslim Transoxania and Iran. Perhaps the use of gunpowder as a propellant, in other words the invention of true guns, appeared first in the Muslim Middle East, whereas the invention of gunpowder itself was a Chinese achievement"

- Chahryar Adle; Irfan Habib (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast: from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Volume 5 of History of Civilizations of Central Asia (illustrated ed.). UNESCO. p. 474. ISBN 92-3-103876-1. https://books.google.com/?id=AzG5llo3YCMC&pg=PA474&dq=Indeed,+it+is+possible+that+gunpowder+devices,+including+Chinese+mortar+(+huochong),+had+reached+Central+Asia+through+the+Mongols+as+early+as+the+thirteenth+century.71+Yet+the+potential+remained+unexploited;#v=onepage. Retrieved 2011-11-28. "Indeed, it is possible that gunpowder devices, including Chinese mortar (huochong), had reached Central Asia through the Mongols as early as the thirteenth century. Yet the potential remained unexploited; even Sultan Husayn's use of cannon may have had Ottoman inspiration."

- M. S. Asimov and C. E. Bosworth, History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Age of Achievement, Part 1, Volume 4, p. 181

- David Morgan, The Mongols, p. 61.

- John Andrew Boyle, ed., The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: "The Saljuq and Mongol Periods". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968, p. 307.

- Ibn al-Athir, The Chronicle, 207

- Ibn al-Athir, The Chronicle, 207.

- Ata-Malik Juvayni, History of The World Conqueror, pp. 160–161 (Boyle's translation)

- Juvayni, World Conqueror, 83–85.

- Ibn al-Athir, The Chronicle, 229

- Ibn al-Athir, The Chronicle, 229.

- Paul Ratchnevsky, Genghis Khan, p. 173

- Morgan, p. 67

- Minhaj Siraj Juzjani, Tabakat-i-Nasiri: A General History of the Muhammadan Dynasties of Asia, trans. H. G. Raverty (London: Gilbert & Rivington, 1881), 1068–1071

- John Man, "Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection", February 6, 2007. Page 180.

- Additionally, the population of roughly the same area (Persia and Central Asia) plus some others (Caucasia and northeast Anatolia) is estimated at 5–6 million nearly 400 hundreds later, under the rule of the Safavid dynasty. Dale, Stephen Frederic (August 15, 2002). Indian Merchants and Eurasian Trade, 1600–1750. ISBN 9780521525978. https://books.google.com/?id=GqEWw_54uVUC&pg=PA18&lpg=PA18&dq=population+of+persia+1600#v=snippet&q=population%20of%20persia%201600&f=false. Retrieved 15 April 2016. Page 19.

- Tertius Chandler & Gerald Fox, "3000 Years of Urban Growth", pp. 232–236

- Chandler & Fox, p. 232: Merv, Samarkand, and Nipashur are referred to as "vying for the [title of] largest" among the "Cities of Persia and Turkestan in 1200", implying populations of less than 70,000 for the other cities (Otrar and others do not have precise estimates given). "Turkestan" seems to refer to Central Asian Turkic countries in general in this passage, as Samarkand, Merv, and Nishapur are located in modern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and northeastern Iran respectively.

- Sverdrup 2017, pp. 148, 150

- Juvayni, Rashid al-Din.

- Frank McLynn, Genghis Khan (2015).

- Sverdrup 2017, p. 148, citing Rashid Al-Din, 107, 356–362.

- Frank Mclynn, Genghis Khan (2015)

- Juvayni, pp. 83–84

- John Man (2007). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. Macmillan. pp. 163. ISBN 978-0-312-36624-7.

- Juvayni, p. 85

- Greene, Robert "The 33 Strategies of War"

- Sverdrup, Carl. The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sube'etei. Helion and Company, 2017. Page 148.

- Christopher P. Atwood, Encyclopedia of Mongolian and the Mongol Empire (Facts on File, 2004), 24.

- Morgan, David The Mongols

- Frank McLynn.

- Sverdrup 2017, p. 148.

- Ibid, p. 151

- McLynn, p. 280

- Nicolle, David. The Mongol Warlords

- Stubbs, Kim. Facing the Wrath of Khan.

- Mongol Conquests http://users.erols.com/mwhite28/warstat0.htm#Mongol