A sadhu (IAST: sādhu (male), sādhvī or sādhvīne (female)), also spelled saddhu, is a religious ascetic, mendicant (monk) or any holy person in Hinduism and Jainism who has renounced the worldly life. They are sometimes alternatively referred to as jogi, sannyasi or vairagi. It literally means one who practises a ″sadhana″ or keenly follows a path of spiritual discipline. Although the vast majority of sādhus are yogīs, not all yogīs are sādhus. The sādhu is solely dedicated to achieving mokṣa (liberation), the fourth and final aśrama (stage of life), through meditation and contemplation of Brahman. Sādhus often wear simple clothing, such saffron-coloured clothing in Hinduism, white or nothing in Jainism, symbolising their sannyāsa (renunciation of worldly possessions). A female mendicant in Hinduism and Jainism is often called a sadhvi, or in some texts as aryika.

- sadhu

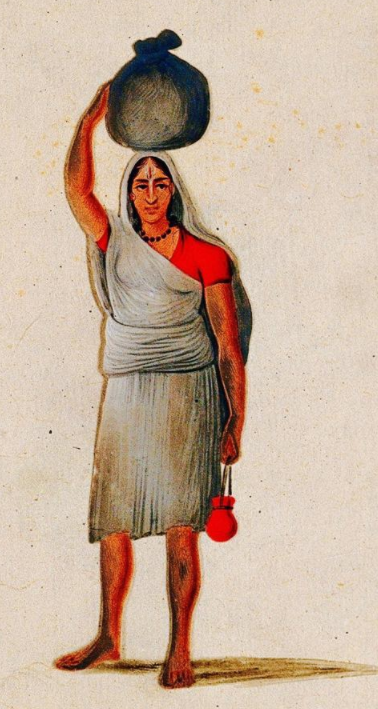

- female

1. Etymology

The term sadhu (Sanskrit: साधु) appears in Rigveda and Atharvaveda where it means "straight, right, leading straight to goal", according to Monier Monier-Williams.[1][2] In the Brahmanas layer of Vedic literature, the term connotes someone who is "well disposed, kind, willing, effective or efficient, peaceful, secure, good, virtuous, honourable, righteous, noble" depending on the context.[1] In the Hindu Epics, the term implies someone who is a "saint, sage, seer, holy man, virtuous, chaste, honest or right".[1]

The Sanskrit terms sādhu ("good man") and sādhvī ("good woman") refer to renouncers who have chosen to live lives apart from or on the edges of society to focus on their own spiritual practices.[3]

The words come from the root sādh, which means "reach one's goal", "make straight", or "gain power over".[4] The same root is used in the word sādhanā, which means "spiritual practice". It literally means one who practises a ″sadhana″ or a path of spiritual discipline.[5]

2. Demographics and Lifestyle

There are 4 to 5 million sadhus in India today and they are widely respected for their holiness.[6] It is also thought that the austere practices of the sadhus help to burn off their karma and that of the community at large. Thus seen as benefiting society, sadhus are supported by donations from many people. However, reverence of sadhus is by no means universal in India. For example, Nath yogi sadhus have been viewed with a certain degree of suspicion particularly amongst the urban populations of India, but they have been revered and are popular in rural India.[7][8]

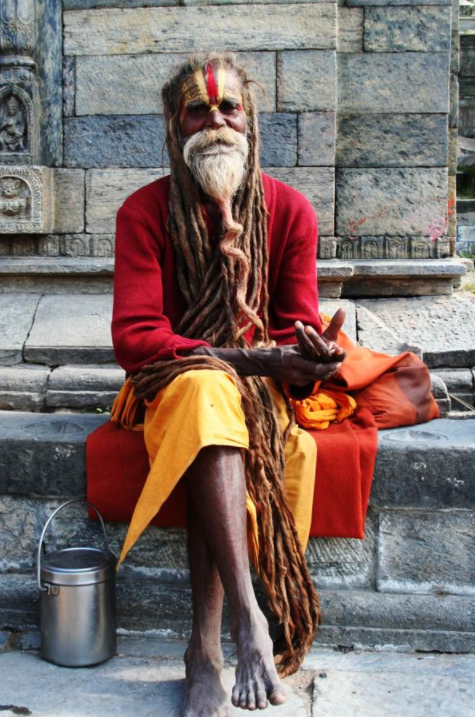

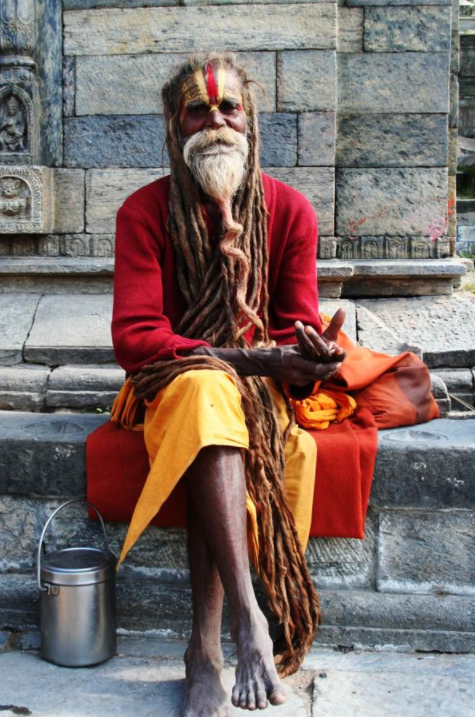

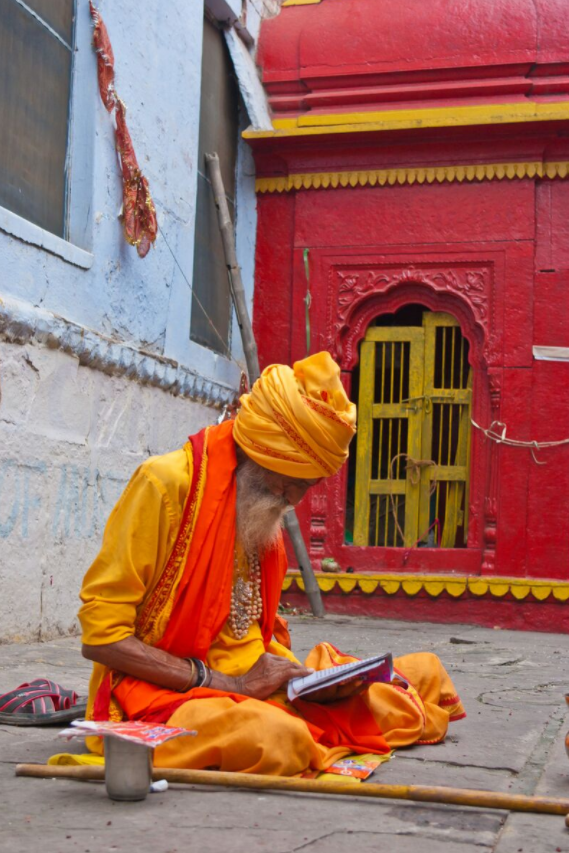

There are naked (digambara, or "sky-clad") sadhus who wear their hair in thick dreadlocks called jata. Sadhus engage in a wide variety of religious practices. Some practice asceticism and solitary meditation, while others prefer group praying, chanting or meditating. They typically live a simple lifestyle, have very few or no possessions, survive by food and drinks from leftovers that they beg for or is donated by others. Many sadhus have rules for alms collection, and do not visit the same place twice on different days to avoid bothering the residents. They generally walk or travel over distant places, homeless, visiting temples and pilgrimage centers as a part of their spiritual practice.[9][10] Celibacy is common, but some sects experiment with consensual tantric sex as a part of their practice. Sex is viewed by them as a transcendence from a personal, intimate act to something impersonal and ascetic.[11]

3. Sadhu Sects

3.1. Hinduism

Shaiva sadhus are renunciates devoted to Shiva, and Vaishnava sadhus are renouncers devoted to Vishnu (or his avatar like Rama or Krishna). The Vaishnava sadhus are sometimes referred to as vairagis.[12] Less numerous are Shakta sadhus, who are devoted to Shakti. Within these general divisions are numerous sects and subsects, reflecting different lineages and philosophical schools and traditions (often referred to as "sampradayas").

Within the Shaiva sadhus are many subgroups. Most Shaiva sadhus wear a Tripundra mark on their forehead, dress in saffron, red or orange color clothes, and live a monastic life. Some sadhus such as the Aghori share the practices of ancient Kapalikas, where they beg with a skull, smeared their body with ashes from the cremation ground, and experiment with substances or practices that are generally abhorred by society.[13][14]

The Dashanami Sampradaya sadhus belong to the Smarta Tradition. They are said to have been formed by the philosopher and renunciant Adi Shankara, believed to have lived in the 8th century CE, though the full history of the sect's formation is not clear. Among them are the Naga subgroups, naked sadhu known for carrying weapons like tridents, swords, canes, and spears. Said to have once functioned as an armed order to protect Hindus from the Mughal rulers, they were involved in a number of military defence campaigns.[15][16] Generally in the ambit of non-violence at present, some sections are known to practice wrestling and martial arts. Their retreats are still called chhaavni or armed camps, and mock duels are still sometimes held between them.

Female sadhus (sadhvis) exist in many sects. In many cases, the women that take to the life of renunciation are widows, and these types of sadhvis often live secluded lives in ascetic compounds. Sadhvis are sometimes regarded by some as manifestations or forms of the Goddess, or Devi, and are honoured as such. There have been a number of charismatic sadhvis that have risen to fame as religious teachers in contemporary India—e.g., Anandamayi Ma, Sarada Devi, Mata Amritanandamayi, and Karunamayi.[17]

3.2. Jainism

The Jain community is traditionally discussed in its texts with four terms: sadhu (monks), sadhvi or aryika (nuns), sravaka (laymen householders) and sravika (laywomen householders). As in Hinduism and Buddhism, the Jain householders support the monastic community.[18] The sadhus and sadhvis are intertwined with the Jain lay society, perform Murtipuja (Jina idol worship) and lead festive rituals, and they are organized in a strongly hierarchical monastic structure.[19] They were a part of Dumont's theory on social stratification, but according to John Cort, the empirical data refutes Dumont thesis.[19] There are differences between the Digambara and Svetambara sadhus and sadhvi traditions.[19]

The Digambara sadhus own no clothes as a part of their interpretation of Five vows, and they live their ascetic austere lives in nakedness. The Digambara sadhvis wear white clothes. The Svetambara sadhus and sadhvis both wear white clothes. According to a 2009 publication by Harvey J. Sindima, Jain monastic community had 6,000 sadhvis of which less than 100 belong to the Digambara tradition and rest to Svetambara.[20]

4. Becoming a Sadhu

The processes and rituals of becoming a sadhu vary with sect; in almost all sects, a sadhu is initiated by a guru, who bestows upon the initiate a new name, as well as a mantra, (or sacred sound or phrase), which is generally known only to the sadhu and the guru and may be repeated by the initiate as part of meditative practice.

Becoming a sadhu is a path followed by millions. It is supposed to be the fourth phase in a Hindu's life, after studies, being a father and a pilgrim, but for most it is not a practical option. For a person to become sadhu needs vairagya. Vairagya means desire to achieve something by leaving the world (cutting familial, societal and earthly attachments).

A person who wants to become sadhu must first seek a guru. There, he or she must perform 'guruseva' which means service. The guru decides whether the person is eligible to take sannyasa by observing the sisya (the person who wants to become a sadhu or sanyasi). If the person is eligible, guru upadesa (which means teachings) is done. Only then, the person transforms into sanyasi or sadhu. There are different types of sanyasis in India who follow different sampradya. But, all sadhus have a common goal: attaining moksha (liberation).

5. Festive Gatherings

Kumbh Mela, a mass-gathering of sadhus from all parts of India, takes place every three years at one of four points along sacred rivers in India, including the holy River Ganges. In 2007 it was held in Nasik, Maharashtra. Peter Owen-Jones filmed one episode of "Extreme Pilgrim" there during this event. It took place again in Haridwar in 2010.[21] Sadhus of all sects join in this reunion. Millions of non-sadhu pilgrims also attend the festivals, and the Kumbh Mela is the largest gathering of human beings for a single religious purpose on the planet; the most recent Kumbh Mela started on 14 January 2013, at Allahabad. At the festival, sadhus appear in large numbers, including those "completely naked with ash-smeared bodies, [who] sprint into the chilly waters for a dip at the crack of dawn".[22]

- Sadhu

-

Sadhus walking on Durbar Square, Kathmandu. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1927410

-

Sadhu from Vârânasî. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1649652

-

Sadhu by the Ghats on the Ganges. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1675810

-

Sadhus at Kathmandu Durbar Square. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1603457

-

A sadhu playing flute. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1298763

-

Sadhu in Varanasi, India. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1883567

-

Sadhu in India. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1357393

-

Sadhvi or female Sadhu at the Gangasagar Fair transit camp, Kolkata. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1314295

-

Sadhu at a river bank. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1981293

-

Sadhu in Nepal. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1559131

References

- Sadhu, Monier Williams Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press, page 1201 http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1200/mw__1234.html

- See for example:अग्ने विश्वेभिः स्वनीक देवैरूर्णावन्तं प्रथमः सीद योनिम् । कुलायिनं घृतवन्तं सवित्रे यज्ञं नय यजमानाय साधु ॥१६॥ – Rigveda 6.15.16 (Rigveda Hymn सूक्तं ६.१५, Wikisource)प्र यज्ञ एतु हेत्वो न सप्तिरुद्यच्छध्वं समनसो घृताचीः । स्तृणीत बर्हिरध्वराय साधूर्ध्वा शोचींषि देवयून्यस्थुः ॥२॥ – Rigveda 7.43.2 (Rigveda Hymn सूक्तं ७.४३, Wikisource)यथाहान्यनुपूर्वं भवन्ति यथ ऋतव ऋतुभिर्यन्ति साधु । यथा न पूर्वमपरो जहात्येवा धातरायूंषि कल्पयैषाम् ॥५॥ – Rigveda 10.18.5 (Rigveda Hymn सूक्तं १०.१८, Wikisource), etc. https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/ऋग्वेद:_सूक्तं_६.१५

- Flood, Gavin. An introduction to Hinduism. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996) p. 92. ISBN:0-521-43878-0

- Arthur Anthony Macdonell. A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. p. 346.

- ″Autobiography of an Yogi″, Yogananda, Paramhamsa,Jaico Publishing House, 127, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Bombay Fort Road, Bombay (Mumbai) - 400 0023 (ed.1997) p.16

- Dolf Hartsuiker. Sadhus and Yogis of India . http://www.adolphus.nl/sadhus/

- White, David Gordon (2012), The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India, University of Chicago Press, pp. 7–8

- David N. Lorenzen and Adrián Muñoz (2012), Yogi Heroes and Poets: Histories and Legends of the Naths, State University of New York Press, ISBN:978-1438438900, pages x-xi

- M Khandelwal (2003), Women in Ochre Robes: Gendering Hindu Renunciation, State University of New York Press, ISBN:978-0791459225, pages 24-29

- Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives, ISBN:978-9042015104, pages 97-98

- Gavin Flood (2005), The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN:978-0521604017, Chapter 4 with pages 105-107 in particular

- Brian Duignan, Sadhu and swami, Encyclopædia Britannica http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/515896/sadhu-and-swami

- Gavin Flood (2008). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 212–213, ISBN:978-0-470-99868-7

- David N. Lorenzen (1972). The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas: Two Lost Śaivite Sects. University of California Press, pp. 4-16, ISBN:978-0-520-01842-6

- 1953: 116; cf. also Farquhar 1925; J. Ghose 1930; Lorenzen 1978

- "The Wrestler's Body". Publishing.cdlib.org. http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft6n39p104&chunk.id=ch09&toc.depth=1&toc.id=ch09&brand=eschol. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Home - Amma Sri Karunamayi". http://www.karunamayi.org/. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- Jaini 1991, p. xxviii, 180.

- Cort, John E. (1991). "The Svetambar Murtipujak Jain Mendicant". Man (Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 26 (4): 651–671. doi:10.2307/2803774. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2803774

- Harvey J. Sindima (2009). Introduction to Religious Studies. University Press of America. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-7618-4762-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=Bki5SZToAUkC&pg=PA100.

- Yardley, Jim; Kumar, Hari (14 April 2010). "Taking a Sacred Plunge, One Wave of Humanity at a Time". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/15/world/asia/15india.html. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Pandey, Geeta (14 January 2013). "Kumbh Mela: 'Eight million' bathers on first day of festival". BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-21017217.