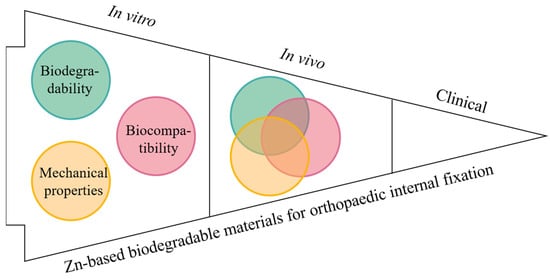

用于内固定的传统惰性材料引起了许多并发症,通常需要通过二次手术去除。可生物降解的材料,如镁(Mg)、铁(Fe)和锌(Zn)基合金,为解决这些问题开辟了新的途径。在过去的几十年中,镁基合金引起了研究人员的广泛关注。然而,仍然需要克服过快的降解速度和氢气释放的问题。Zn合金具有与传统金属材料(例如钛(Ti))相当的机械性能,并且具有中等的降解速率,可能作为内部固定材料的良好候选者,特别是在骨架的承重部位。近年来,新兴的Zn基合金和复合材料被开发出来,并进行了体外和体内研究,以探索其生物降解性,机械性能和生物相容性,以朝着骨折固定临床应用的最终目标迈进。本文对Zn基生物降解材料的相关研究进展进行综述,以期为今后Zn基生物降解材料在骨科内固定中的应用提供有益的参考。

- Zinc-based biodegradable materials

- orthopedic implant

- biodegradability

- mechanical property

- biocompatibility

1. Introduction简介

Cast | |||||||||

86 |

140 |

1.2 |

SBF |

- |

MG63 |

Adding the alloying elements Mg, Ca and Sr into Zn can significantly increase the viability of MG63 and can promote the MG63 cell proliferation compared with the pure Zn and negative control groups. |

[77] |

||

|

Zn-1.0Ca-1Sr HE |

212 |

260 |

6.7 |

SBF |

0.11 |

||||

|

Zn-1.0Ca-1Sr HR |

144 |

203 |

8.8 |

SBF |

- |

||||

|

Zn-0.8Li-0.4Mg HE |

438 |

646 |

3.68 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[24] |

|

|

Zn-3Ge-0.5Mg Cast |

66.9 |

88.3 |

1.4 |

HBSS |

0.062 |

MG63 |

The extract with a concentration of 100% had obvious cytotoxicity to MG63 cells. When the concentration of the extract was diluted to 12.5% or lower, the survival rate of MG-63 cells was all above 90%. |

[78] |

|

|

Zn-3Ge-0.5Mg HR |

253 |

208 |

9.2 |

HBSS |

0.075 |

||||

|

Zn-4Ag-0.6Mn HE |

- |

302 |

35 |

HBSS |

0.012 |

- |

- |

[79] |

|

|

Zn-1Fe-1Mg Cast |

146 |

157 |

2.3 |

SBF |

0.027 |

- |

- |

[80] | |

| Classification分类 | Materials材料 | Biodegradability生物降解性 | Mechanical Properties机械性能 | Biocompatibility生物相容性 | Applications or Potential Applications应用或潜在应用 | Ref.裁判。 |

|---|

2.2. Biodegradability of Zn-Based Alloys

2.3. Biodegradability of the Zn-Based Composites

Zn-0.8Mn-0.4 | |||||||||

Cast | |||||||||

112 | |||||||||

120 |

0.3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

[68] |

|||

|

Zn-0.8Mn-0.4 HE |

253 |

343 |

8 |

- |

- |

||||

|

Zn-0.8Mn-0.4 HR |

245 |

323 |

12 |

- |

- |

||||

| Composition (wt%) | Mechanical Properties | Corrosion Test | Cytocompatibility | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σYS (MPa) | σUTS (MPa) | ε (%) | Corrosion Medium | Corrosion Rate (mm y−1) |

Cell Type | Key Findings | ||

4. Biocompatibility of Zn-Based Biodegradable Materials

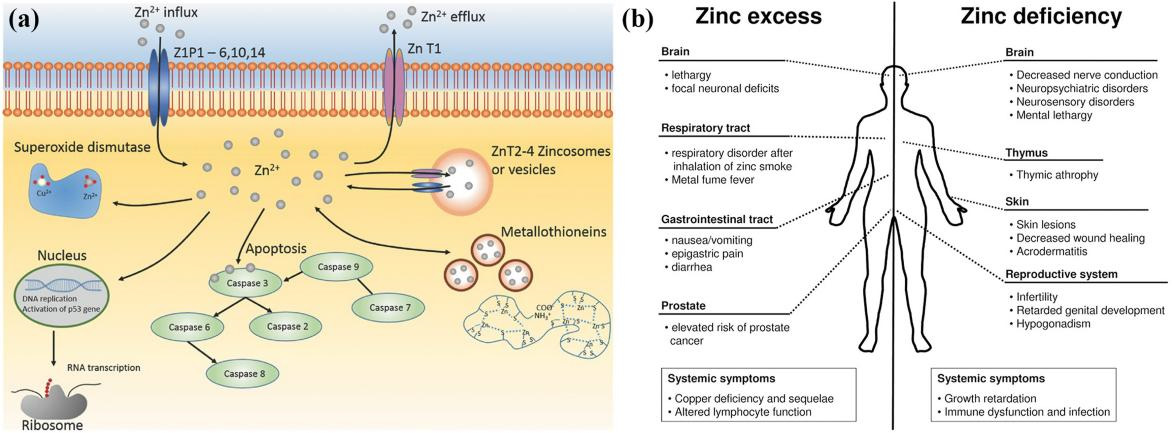

Biocompatibility is the ability of a material to conform to the host response, cell response, and living systems, and it is a vital property of metallic internal fixation for bone repair [1]. The metallic fixation implants directly release ions into the human body, affecting the surrounding cells, tissues, and blood (Figure 4) and leading to either positive or negative results [47,81,82]. Additionally, biomaterial-induced infections are one of the leading causes of implant failure in orthopaedic surgery [25]. Postoperative wound infection may cause an increase in the cost of pain treatment and even sequelae such as limb malformation and dysfunction of the implants [26]. Thus, exploring the biocompatibility of Zn and its alloys is important considering their ultimate implanting in the human body.

Figure 4. (a) Biological roles of Zn. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [81], Copyright 2016 Wiley. (b) Comparison of the inflfluence of zinc excess versus defificiency [82].

4.1. Biocompatibility of Pure Zn

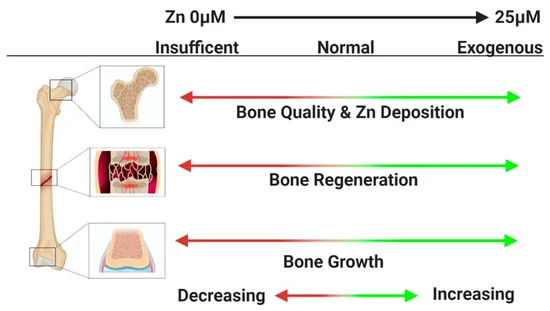

Zn plays a fundamental role in multiple biochemical functions of the human body, including cell division, cell growth, wound healing, and the breakdown of carbohydrates [83]. Dietary Zn2+ deficiency has been linked to impaired skeletal development and bone growth in humans and animals (Figure 5) [83]. Specifically, 85% of Zn in the human body is found in muscle and bone, 11% in the skin and liver, and the rest in other tissues [84]. Zn is located at sites of soft tissue calcification, including osteons and calcified cartilage. Zn levels in bone tissue increase as bone mineralization increases. The skeletal growth was reduced during Zn deficiency. Zn plays a key biological role in the development, differentiation and growth of various tissues in the human body [85], including nucleic acid metabolism, stimulation of new bone formation, signal transduction, protection of bone mass, regulation of apoptosis, and gene expression [14]. Zn not only inhibits related diseases such as bone loss and inflammation, but also plays an important role in cartilage matrix metabolism and cartilage II gene expression [86]. The following symptoms are associated with Zn deficiency, including impaired physical growth and development in infants and young adults, the increased risk of infection, the loss of cognitive function, the problems of memory and behavioral, and learning disability. However, excessive Zn may cause neurotoxicity problems [87]. Based on the RDI (Reference Daily Intake) values reported for mature adults, the biocompatibility of Zn (RDI: 8–20 mg/day) is not as good as that of Mg (RDI: 240–420 mg/day), but very similar to that of Fe (RDI: 8–18 mg/day) [88]. Excessive Zn can cause symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, and can weaken immune function and delay bone development [87]. Therefore, when Zn-based biodegradable materials are implanted into the body as bone implant materials, the toxicity of their degradation products should be considered.

Figure 5. Zn2+ deficiency has been linked to impaired skeletal development and bone growth in humans and animals [83].

4.2. Biocompatibility of Zn-Based Alloys

The results of cytotoxicity tests can reflect the biological safety of the material to some extent. Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the results of cytocompatibility testing of alloying elements. Specifically, according to the cytocompatibility testing, additions of Mg, Ca and Li do not produce cytotoxicity, but can promote cell proliferation. However, Cu, Al, and Fe show varying degrees of toxic effects on bone cells [34,37,40,42,43,73,74,89]. Regarding the effect of metal ions on antibacterial activity, Sukhodub et al. [90] systematically examined the antibacterial abilities of metal ions and reported that the sterilization rate of the metal ions from high to low was as follows: Ag, Cu+2+, Zn2+, and Mg2+. Among these metal ions, Zn ions have a good antibacterial ability when they reach a certain concentration and can kill various bacteria and fungi. Zinc is an essential element with intrinsic antibacterial and osteoinductive capacity [91]. Zn-based antimicrobial materials generally consist of zinc complexes and ZnO nano-particles. Complexes such as zinc pyrithione and its derivatives are well known antifungal compounds and have been broadly applied in medicines [92]. Lima et al. [93] prepared Zn-doped mesoporous hydroxyapatites (HAps) with various Zn contents by co-precipitation using a phosphoprotein as the porous template. They found that the antibacterial activity of the HAps samples depended strongly on their Zn2+ contents. Tong et al. [94] examined the bacterial distributions of the Zn-Cu foams pre- and post-heat treatment after co-culturing with staphylococcus aureus for 24 h, and observed good antibacterial properties of the Zn-Cu foams. Lin et al. [74] observed better antibacterial properties of Zn-1Cu-0.1Ti than pure Zn. Ren et al. [95] systematically investigated a variety of Cu-containing medical metals including stainless steels, Ti alloys, and Co-based alloys, and demonstrated good antibacterial abilities of those materials stemming from the durable and broad-spectrum antibacterial characteristics of Cu ions. Therefore, Cu-containing Zn alloys may be expected to be promising implant materials with intrinsic antibacterial ability.4.3. Biocompatibility of Zn-Based Composites

HA is a well-known bioceramic with bioactivity that supports cell proliferation, bone ingrowth and osseointegration. HA has similar chemical and crystallographic structures to bone, which can form a chemical bond with osseous tissue, and act like nucleation for new bone [17]. Yang et al. [55] fabricated Zn-(1, 5, 10 wt%) HA composites using the SPS technique and investigated their in vitro degradation behaviors. Zn-HA composites showed significantly improved cell viability of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells compared with pure Zn. An effective antibacterial property was observed as well. As a bioactive ceramic, β-TCP has good biocompatibility, osteoconductivity and biodegradability [96]. In a study by Pan et al. [56], the biocompatibility of Zn-1Mg-xβ-TCP (x = 0, 1, 3, 5 vol%) composites were investigated. When L-929 and MC3T3 cells were cultured in different concentrations for one day, the relative proliferation rate of the cells is above 80%, and the cytotoxicity is 0–1. Moreover, the addition of β-TCP makes the compatibility of the composite material to MC3T3 cells significantly higher than that of the Zn-Mg alloy.

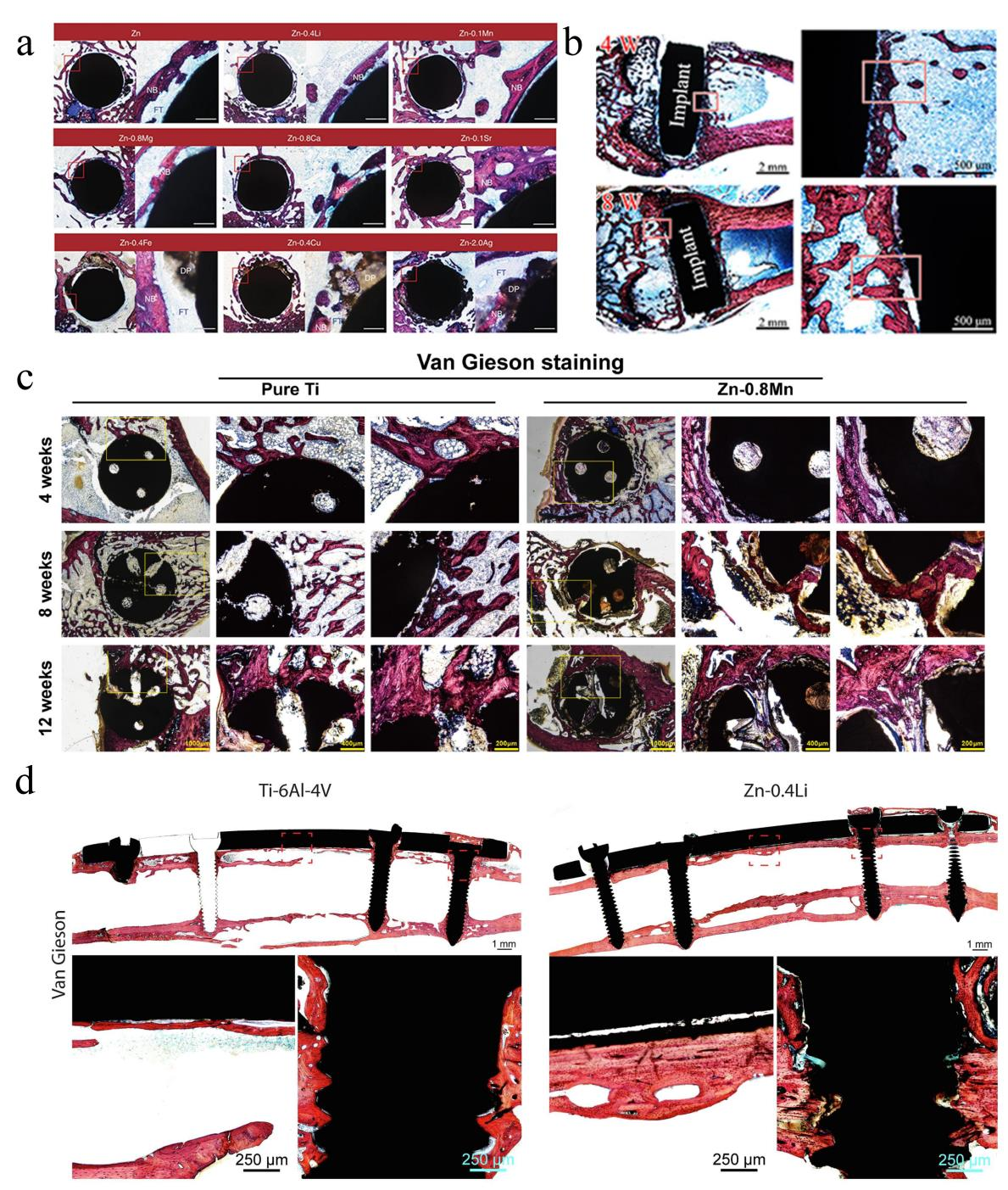

5. In Vivo Evaluation of Zn-Based Biodegradable Materials with Animal Models

In addition to in vitro testing, in vivo animal experiments are a necessary step in assessing the performances of Zn-based biodegradable materials prior to translation into clinical applications. Different from in vitro experiments where the biodegradability, mechanical property, and biocompatibility of a material are often tested separately, animal models can be used to examine all these properties together in an in vivo condition. Although the in vivo animal experiments may not be able to fully mimic the mechanical, biological and chemical environments in the human body, they are currently the best way to evaluate the interactions between Zn-based biodegradable materials and host [15,24,25,36,97]. There are far fewer in vivo studies on Zn-based biomaterials than in vitro studies. Several representative in vivo studies on Zn-based biodegradable materials were summarized in Table 4. Yang et al. [24] implanted the pure Zn into the rat femur condyle. A serious fibrous tissue encapsulation was found for pure Zn, resulting in the lack of direct bonding between bone and implant (Figure 6a). The delayed osseointegration of pure Zn is claimed to be attributed to the local high Zn ion concentration. Consistent with the observations in vitro, the in vivo results confirmed that alloying with appropriate elements such as Mg, Ca and Sr can effectively improve the biocompatibility. Yang et al. [55] implanted the pure Zn into the rat femur condyle. A serious fibrous tissue encapsulation was found for pure Zn, resulting in the lack of direct bonding between bone and implant (Figure 6b). Meanwhile, Jia et al. [70] implanted the Zn-0.8 wt.%Mn alloy into the rat femoral condyle for repairing bone defects with pure Ti as control. Their results showed that the new bone tissue at the bone defect site in both groups gradually increased with time, but a large amount of new bone tissue was observed around the Zn-0.8Mn alloy scaffold (Figure 6c). More importantly, in a heavy load-bearing rabbit shaft fracture model, the Zn-0.4Li-based bone plates and screws showed comparable performance in bone fracture fixation compared to the Ti-6Al-4 V counterpart whereas the cortical bone in the Zn-0.4Li alloy group was much thicker (Figure 6d). The results suggest the great potential of Zn-Li based alloys for degradable biomaterials in heavy load-bearing applications [25]. Figure 6. (a) Hard tissue sections of pure Zn, Zn-0.4Li, Zn-0.1Mn, Zn-0.8 Mg, Zn-0.8Ca, Zn-0.1Sr, Zn-0.4Fe, Zn-0.4Cu and Zn-2Ag in metaphysis. The magnified region is marked by red rectangle. NB, new bone; DP, degradation products; FT, fibrous tissue. Scale bar, 0.5 mm in low magnification, 500 μm in high magnification [24]. (b) Histological characterization of hard tissue sections at implant sites. Van Gieson staining of pure Zn. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [55], Copyright 2018, Elsevier. (c) The Van Gieson staining results of specimens 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks postoperatively. Within each row, full-view images of bone defect areas (20×), medium magnification images (50×), and higher magnification images (100×) arranged from left to right. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [70], Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (d) Van Gieson staining of representative histological images of femoral fracture healing at 6 months. The fracture healing and fixation screws are magnified and marked by red rectangles. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [25], Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

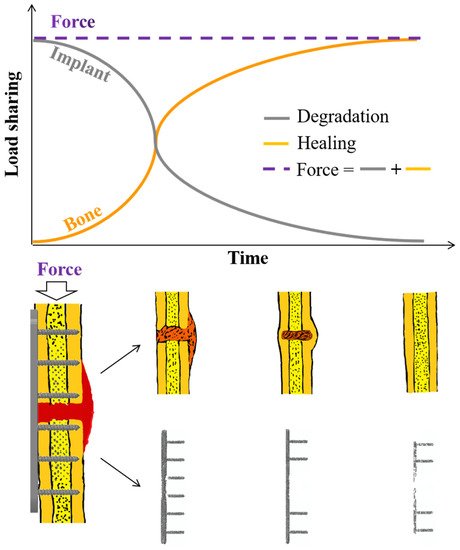

It can be seen from those in vivo studies above (Table 4) that the Zn-based biodegradable materials play an important role in promoting osteogenesis. The corrosion rate of Zn-based biodegradable materials is relatively slow in vivo and can provide a long-term mechanical support in the period of fracture healing [24,25,36]. No incomplete fracture healing and structural collapse of the implant were reported during the animal experiments on load-bearing parts such as the femur [25]. However, the long-term results of the Zn-based implants remain unknown since those animal studies generally lasted for 8–24 weeks [24,25,46]. Additionally, the in vivo studies testing performances of Zn-based implants in fracture fixation are limited [24].

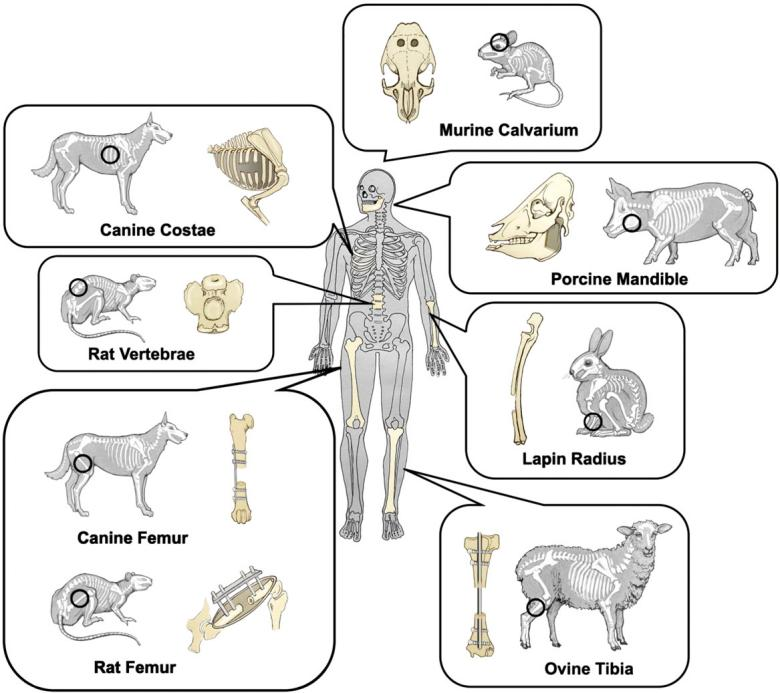

Currently, only small animal models, such as mice, rats and rabbits have been used to examine primarily the biodegradability and biocompatibility of Zn2+ metals on bone defect sites (Table 4) [24,25,33,36,46,51,55,56,70,97]. Although mammals have many similarities, differences across small animals, large animals and humans should be recognized [98]. For example, the difference in skeletal size across various species affects the amount of Zn materials that needs to be degraded or absorbed as well as the mechanical environment, which may lead to varied results between preclinical studies and clinical applications. Therefore, with clinical translations in mind, future studies may be warranted with large animal models. In addition, as Zn-based implants are expected to be used at heavy load-bearing sites for internal fracture fixation, proper site-specific in vivo animal models should be used to test their biodegradability, mechanical properties and biocompatibility (Figure 7).

Figure 6. (a) Hard tissue sections of pure Zn, Zn-0.4Li, Zn-0.1Mn, Zn-0.8 Mg, Zn-0.8Ca, Zn-0.1Sr, Zn-0.4Fe, Zn-0.4Cu and Zn-2Ag in metaphysis. The magnified region is marked by red rectangle. NB, new bone; DP, degradation products; FT, fibrous tissue. Scale bar, 0.5 mm in low magnification, 500 μm in high magnification [24]. (b) Histological characterization of hard tissue sections at implant sites. Van Gieson staining of pure Zn. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [55], Copyright 2018, Elsevier. (c) The Van Gieson staining results of specimens 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks postoperatively. Within each row, full-view images of bone defect areas (20×), medium magnification images (50×), and higher magnification images (100×) arranged from left to right. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [70], Copyright 2020, Elsevier. (d) Van Gieson staining of representative histological images of femoral fracture healing at 6 months. The fracture healing and fixation screws are magnified and marked by red rectangles. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [25], Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

It can be seen from those in vivo studies above (Table 4) that the Zn-based biodegradable materials play an important role in promoting osteogenesis. The corrosion rate of Zn-based biodegradable materials is relatively slow in vivo and can provide a long-term mechanical support in the period of fracture healing [24,25,36]. No incomplete fracture healing and structural collapse of the implant were reported during the animal experiments on load-bearing parts such as the femur [25]. However, the long-term results of the Zn-based implants remain unknown since those animal studies generally lasted for 8–24 weeks [24,25,46]. Additionally, the in vivo studies testing performances of Zn-based implants in fracture fixation are limited [24].

Currently, only small animal models, such as mice, rats and rabbits have been used to examine primarily the biodegradability and biocompatibility of Zn2+ metals on bone defect sites (Table 4) [24,25,33,36,46,51,55,56,70,97]. Although mammals have many similarities, differences across small animals, large animals and humans should be recognized [98]. For example, the difference in skeletal size across various species affects the amount of Zn materials that needs to be degraded or absorbed as well as the mechanical environment, which may lead to varied results between preclinical studies and clinical applications. Therefore, with clinical translations in mind, future studies may be warranted with large animal models. In addition, as Zn-based implants are expected to be used at heavy load-bearing sites for internal fracture fixation, proper site-specific in vivo animal models should be used to test their biodegradability, mechanical properties and biocompatibility (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Schematic representation of common animal bone defect models [98].

Table 4. Relevant animal studies of Zn-based biodegradable materials as potential orthopaedic implants.

|

Zn-Based Metals |

Designed Implants |

Control |

Surgeries |

Animal Species |

Major Findings |

Ref. |

||||||||

|

Zn-Mn |

Scaffold |

Pure Ti |

Insertion into femoral condyle |

Rats |

The new bone tissues at the bone defect sites gradually increased with time in both groups, and numerous new bone tissues were observed around the Zn-0.8Mn alloy scaffold |

[70] |

||||||||

|

Zn-1Mg, Zn-1Ca, Zn-1Sr |

Intramedullary nails |

NA |

Insertion into femoral marrow medullary cavity |

Mice |

There was no inflammation observed around the implantation site and no mouse died after operation. The new bone thickness of Zn-1Mg, Zn-1Ca and Zn-1Sr pin groups are significantly larger than the sham control group. |

[51] |

||||||||

|

Zn-HA |

Pin |

Pure Zn |

Insertion into femoral condyle |

Rats |

There was new bone formation around the Zn-HA composite, and the bone mass increased over time. With prolonged implantation time, the Zn-HA composite was more effective than pure Zn in promoting new bone formation. |

[55] |

||||||||

|

Zn-0.05Mg |

Pin |

Pure Zn |

Insertion into femoral condyle |

Rabbits |

No inflammatory cells were found at the fracture site, and new bone tissue formation was confirmed at the bone/implant interface, proving that the Zn-0.05Mg alloy promoted the formation of new bone tissue. | |||||||||

| Non-biodegradable metallicmaterials不可生物降解的金属材料 | 316L SS不锈钢 | Non-biodegradable不可生物降解 | High elastic modulus, low wear and corrosion resistance, high tensile strength高弹性模量,低磨损和耐腐蚀性,高拉伸强度 | High biocompatibility高生物相容性 | Acetabular cup, bone screws, bone plates, pins, etc.髋臼杯、骨螺钉、骨板、销钉等 | [ | ||||||||

| Zn-0.8Mg | 203 | 301 | 13 | MEM | 0.071 | 11] | ||||||||

| U-2OS, | L-929 | Zn is less biocompatible than magnesium and the maximum safe concentrations of Zn | 2+ | for the U-2OS and L929 cells are 120 μM and 80 μM. | [ | 50 | ] | Co–Cr alloys钴铬合金 | Non-biodegradable不可生物降解 | High elastic modulus, high wear and corrosion resistance高弹性模量,高耐磨性和耐腐蚀性 | Low biocompatibility低生物相容性 | Bone screws, bone plates, femoral stems, total hip replacements, etc.骨螺钉、骨板、股骨干、全髋关节置换术等。 | [12] | |

| Zn-1.0Ca | 206 | 252 | 12.7 | HBSS | 0.09 | MG63 | Adding the alloying elements Ca into Zn can significantly increase the viability of MG63 and can promote the MG63 cell proliferation compared with the pure Zn and negative control groups. | [51] | Ti alloys钛合金 | Non-biodegradable不可生物降解 | Poor fatigue strength, light weight疲劳强度差,重量轻 | High biocompatibility高生物相容性 | ||

| Zn-1.1Sr | 220 | 250 | Dental implants, bone screws, bone plates, etc. | 种植牙、骨螺钉、骨板等 | 22[11 | SBF,13]11,13 ] | ||||||||

| 0.4 | Biodegradable metallic materials可生物降解的金属材料 | Mg-based alloys镁基合金 | Biodegradable, high degradation rate可生物降解,降解率高 | Poor mechanical properties, elastic modulus are close to cortical bone力学性能差,弹性模量接近皮质骨 | 高生物相容性,High biocompatibility, H2 evolution演化 | Bone screws, bone plates (non-load bearing parts), etc.接骨螺钉、接骨板(非承重部件)等 | [2,,9] | |||||||

| Fe-based alloys铁基合金 | Biodegradable, low degradation rate可生物降解,降解率低 | High elastic modulus, poor mechanical properties弹性模量高,机械性能差 | Low biocompatibility低生物相容性 | Bone screws, bone plates, etc.骨螺钉、骨板等 | [9] | |||||||||

| Zn-based alloys锌基合金 | Biodegradable, moderate corrosion rate可生物降解,腐蚀速度适中 | High elastic modulus, high mechanical properties, low creep resistance高弹性模量、高机械性能、低抗蠕变性 | Cytotoxicity, no gas production, high biocompatibility细胞毒性大,不产气,生物相容性高 | Bone screws, bone plates (load-bearing parts (potential applications)), etc.接骨螺钉、接骨板(承重部件(潜在应用))等 | [3,,9,,10] |

2. Biodegradability of Zn-Based Biodegradable Materials锌基生物降解材料的生物降解性

2.1. Biodegradability of Pure Zn

| HOBs, hMSCs |

| The proliferation ability of the two kinds of cells did not decrease in the zinc alloy leaching solution. When the concentration of the leaching solution was low, the growth of the two kinds of cells was promoted. | ||||||||

| [ | 32 | ] | ||||||

| Zn-0.4Li | 387 | 520 | 5.0 | SBF | 0.019 | MC3T3-E1 | Zn-0.4Li alloy extract can significantly promote the proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells. | [24] |

| Zn-5.0Ge | 175 | 237 | 22 | HBSS | 0.051 | MC3T3-E1 | The diluted extracts at a concentration 12.5% of both the as-cast Zn-5Ge alloy and pure Zn showed grade 0 cytotoxicity; the diluted extracts at the concentrations of 50% and 25% of Zn-5Ge alloy showed a significantly higher cell viability than those of pure Zn. | [52] |

| Zn-6.0Ag | - | 290 | - | SBF | 0.114 | - | - | [44] |

| Zn-0.8Fe | 127 | 163 | 28.1 | SBF | 0.022 | MC3T3-E1 | MC3T3-E1 cells had unhealthy morphology and low cell viability. | [24] |

| Zn-4Cu | 327 | 393 | 44.6 | HBSS | 0.13 | L-929, TAG, SAOS-2 |

Zn-4Cu alloy had no obvious cytotoxic effect on L929, TAG and Saos-2 cells. | [53] |

| Zn-0.8Mn | 98.4 | 104.7 | 1.0 | - | - | L-929 | Zn-0.8Mn alloy showed 29% to 44% cell viability in 100% extract, indicating moderate cytotoxicity. | [40] |

| Zn-2Al | 142 | 192 | 12 | SBF | 0.13 | MG63 | Cell viability decreased to 67.5 ± 5.3% in 100% extract cultured for one day, indicating that high concentrations of ions have a negative effect on cell growth. With the extension of culture time, the number of cells increased significantly. | [42] |

| Zn-0.0.5Zr | 104 | 157 | 22 | - | - | - | - | [54] |

2.4. Biodegradability of Zn-Based Biomaterials under Mechanical Loading

3. Mechanical Properties of Zn-Based Biodegradable Materials

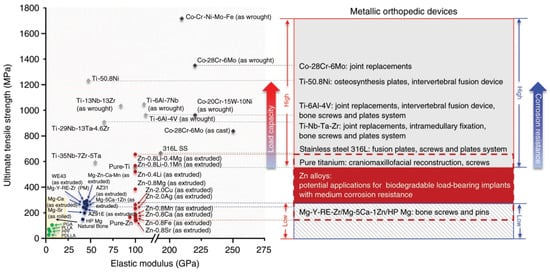

In addition to the biodegradable properties, the mechanical properties of the biodegradable metals are also important considerations for designing orthopaedic implants for internal fixation. Yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), elongation (ε) and elastic modulus (E) are common parameters which are used to indicate the mechanical properties of biomedical materials [11,37,70,71,72,73]. Extensive studies have determined those mechanical parameters of Zn-based biodegradable materials. The reported mechanical criteria for degradable metals (e.g., Mg-based) are UTS 300 MPa and ε 20% [22]. On the other hand, the current gold standard for medical metal materials, such as Ti and its alloys, has a tensile strength of over 600 MPa [13]. To certain extent, these criteria could provide guides of mechanical properties for development of Zn-based degradable materials. However, the requirement may vary with different load-bearing sites.3.1. Mechanical Properties of Pure Zn

Pure Zn has extremely low yield strength (29.3 MPa) and elongation (1.2%) in its as-cast condition [74]. The Young’s modulus of pure Zn is around 94 GPa [16]. Obviously, it is difficult to meet the mechanical criteria as biodegradable metals [22]. On the other hand, owing to the low melting point of Zn, several additional uncertainties exist with regard to the mechanical properties of biodegradable Zn and Zn-based alloys. Low creep resistance, high susceptibility due to natural aging, and static recrystallization may lead to the failure of Zn-based biodegradable materials during storage at a room temperature and usage at a body temperature [26]. Studies showed that Zn-based alloys underwent appreciable creep deformation under human body temperature (37°) [75]. In addition, recrystallization of Zn-based alloys under stress can reduce their resistance to creep [42]. Thus, creep deformation is an important factor that should be considered in the studies of pure Zn.3.2. Mechanical Properties of Zn-Based Alloys

Alloying is a common approach to change the mechanical properties of metals, where alloy ratio is essential for studies of Zn-based alloys. Attempts have been made to optimizing the Zn-based alloys by changing the alloy ratio, in order to obtain better mechanical performance in vitro and then move to in vivo conditions [24,32,40,42,44,50,51,52,53,54]. Zn-based alloys have Young’s modulus values ranging from 100 to 110 GPa depending on alloying conditions [16]. As summarized in Table 2, the Zn-based alloys with improved mechanical properties to various degrees are generated by adding elements of Mg [50], Ca [51], Sr [32], Li [24], Ge [52], Ag [44], Fe [24], Cu [53], Mn [40], Al [42], Zr [54]. The improvement of adding Li elements is particularly obvious, but the elongation of Zn-Li is only 5%. Following addition of the Cu element, the elongation of the Zn-based alloys reaches 44.6%. Binary Zn-based alloys have poor mechanical properties and may not be applicable in load-bearing sites of the skeleton. Table 3 summarizes the mechanical properties of ternary Zn-based alloys on the basis of binary Zn-based alloys. Different mechanical processing methods have great influences on the mechanical properties of the same Zn-based alloys. Among the three common mechanical processing operations (hot extrusion, hot rolling, and casting), the hot extrusion can produce the greatest improvement in mechanical properties of Zn-based alloys. Compared with binary Zn-based alloys, ternary Zn-based alloys have largely improved mechanical properties. For example, the tensile strength of Zn-0.8Li-0.4Mg is 646 MPa, which is greater than those of pure titanium or 316L SS (Figure 1) [24]. In addition, reasonable mechanical integrity of Zn-0.8Li-0.4Mg was maintained in vitro, and is expected to be used for bone repair at load-bearing sites.3.3. Mechanical Properties of Zn-Based Composites

Apart from the addition of alloying elements, adding reinforcement matrix as composite could also regulate the mechanical properties of Zn metals. The biocompatibility and the mechanical properties were improved by controlling the type and content of the second phase to form a composite material. In a previous study, Zn-HA composites were prepared with pure Zn as matrix and hydroxyapatite (HA) as reinforcement by spark plasma sintering [55]. In vivo tests showed that the addition of HA resulted in a better performance in osteogenesis with prolonged fixation time. In another study, Zn-Mg-β-TCP composites were prepared with Zn-Mg as matrix and β-TCP as enhancer by the mechanical stirring combined with ultrasonic assisted casting and hot extrusion technology [56]. This material had an ultimate tensile strength of 330.5 MPa and showed better biocompatibility than Zn-Mg alloys in cellular experiments. A barrier layer of ZrO2 nanofilm was constructed on the surface of Zn-0.1 wt%Li alloy via atomic layer deposition (ALD) [76]. Their results indicated that the addition of ZrO2 could effectively improve cell adhesion and vitality, and promote osseointegration, but the non-degradation of ZrO2 brought new challenges. Composites often have advantages over alloys due to the addition of second-phase enhancers. Compared with pure Zn, the addition of a second-phase material largely enhances its mechanical strength and biocompatibility. However, it was reported that the ductility of Zn-based composite materials is only 10% or even lower, with a greater brittleness [22], bringing difficulties to the processing of orthopaedic devices (such as bone screws and bone plates). In addition, the complex manufacturing process, high cost of composite materials, and a lack of sufficient basic theoretical supports in the field of preparation and processing still limit their developments. Table 3. In vitro experiments of ternary Zn-based alloys.|

Composition (wt%) and Manufacturing Process |

Mechanical Properties |

Corrosion Test |

Cytocompatibility |

Ref. |

|||||

|

σYS (MPa) |

σUTS (MPa) |

ε (%) |

Corrosion Medium |

Corrosion Rate (mm/y) |

Cell Type |

Key Findings |

|||

|

Zn-1.5Mg-0.5Zr HE |

350 |

425 |

12 |

- |

- |

L-929 |

Overall, the L-929 cells exhibit polygonal or spindle shape, and well spread and proliferated in the extracts of pure Zn and Zn alloys. |

[39] |

|

|

Zn-1.0Ca-1Sr | |||||||||

[46] | |||||||||

|

Zn-(0.001% < Mg < 2.5%, 0.01% < Fe < 2.5%) |

Screw and plate |

PLLA, Ti-based alloys |

Mandible fracture |

Beagles |

The new bone formation in the Zn alloy group and the titanium alloy group was significantly higher than that in the PLLA group. In addition, the new bone formation in the Zn-based alloys group was slightly higher than that in the Ti-based alloys group. The degradation of Zn implants in vivo would not increase the concentration of Zn2+. |

[96] |

|||

|

Zn-X (Fe, Cu, Ag, Mg, Ca, Sr, Mn, Li) |

Intramedullary nails |

Pure Zn |

Insertion into femoral marrow medullary cavity |

Rats |

Pure Zn, Zn-0.4Fe, Zn-0.4Cu and Zn-2.0Ag alloy implants showed localized degradation patterns with local accumulation of products. In contrast, the degradation of Zn-0.8Mg, Zn-0.8Ca, Zn-0.1Sr, Zn-0.4Li and Zn-0.1Mn was more uniform on the macroscopic scale. |

[24] |

|||

|

Zn-0.8Sr |

Scaffold |

Pure Ti |

Insertion into femoral condyle |

Rats |

Zn-based alloys promote bone regeneration by promoting the proliferation and differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells, upregulating the expression of osteogenesis-related genes and proteins, and stimulating angiogenesis. |

[36] |

|||

|

Zn-0.8Li-0.1Ca |

Scaffold |

Pure Ti |

Insertion into radial defect |

Rabbits |

The Zn-0.8Li-0.1Ca alloy has a similar level of biocompatibility to pure titanium, but it promotes regeneration significantly faster than pure Ti. |

[33] |

|||

|

Zn-0.4Li |

Screw and plate |

Ti-6Al-4V |

Femoral shaft fracture |

Rabbits |

Plates and screws made of Zn-0.4Li alloy showed comparable performance to Ti-6Al-4V in fracture fixation, and the fractured bone healed completely six months after surgery. |

[25] |

|||

|

Zn-1Mg-nvol%β-TCP (n = 0, 1) |

Columnar samples |

Zn-1Mg |

Specimens in lateral thighs. |

Rats |

Zn-1Mg alloy and Zn-1Mg-β-TCP composites had no significant tissue inflammation and showed good biocompatibility. |

[56] |

|||

6. Summary and Future Directions

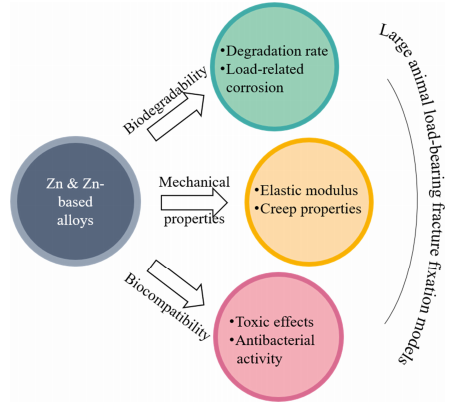

A growing number of new Zn-based biodegradable materials have been developed and their biodegradability, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility were tested mostly in vitro and partially in vivo. An ideal biodegradable material for orthopaedic internal fixation should have a suitable combination of biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical properties (YS, UTS, and ε). Although the mechanical properties of pure Zn are difficult to meet the requirements of orthopaedic fixation, Zn-based alloys can achieve the mechanical properties of traditional implants used in internal fixation at load-bearing sites. Zn-based materials have a moderate corrosion rate and good biocompatibility. Their degradation by-product Zn2+ can promote bone growth and mineralization. These properties support Zn-based biodegradable materials as an alternative for internal fixation implants at heavy load-bearing skeletal sites. However, many questions still need to be addressed before Zn-based biodegradable materials can be used for fracture fixation in clinics (Figure 8).

图8.Zn基生物降解材料的未来发展方向。

在生物降解性方面,(1)目前Zn基生物降解材料的降解速度仍然相对较慢,需要根据目标骨骼部位进一步调整以匹配其愈合速度;(2)由于骨架上存在静载荷和动载荷,需要更好地了解材料的应力腐蚀和疲劳腐蚀。在力学性能方面,(1)目前Zn基生物降解材料的弹性模量(94–110 GPa)高于骨,在用于内固定时应降低弹性模量以避免应力屏蔽;(2)Zn基合金在人体生理温度下对内固定植入物失效的蠕变效应应进一步探讨。在生物相容性方面,(1)由于锌含量高2+对细胞有毒性作用,应尽量调节内固定的降解速率,确保降解产物的浓度不超过植入部位的安全浓度范围;(2)抗菌特性可进一步探索。此外,体内实验应从小动物模型转向大型动物模型,以进行重载骨折固定。

引用

- 帅;李淑贞;彭淑贤;冯平;赖英;Gao,C.可生物降解的金属骨植入物。母校化学前线。2019,3, 544–562.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 傅,R.;冯彦;刘燕;威利;杨华.动态化时间和程度对骨愈合的综合影响。J. 骨科2022,40, 634–643.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 傅,R.;冯彦;伯特兰;杜彤;刘燕;威利;通过速率变化分心提高分心成骨的效率:一项计算研究。国际分子科学2021,22, 11734.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 塔克,A.成人常见上肢骨折的管理。外科2022,40, 184–191。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 吴旭明;比西尼亚诺;詹姆斯;阿巴迪;阿贝迪;阿布-加尔比,E.;阿尔哈桑;阿利普尔,V.;阿拉布卢;阿萨德;等。1990-2019 年 204 个国家和地区的全球、区域和国家骨折负担:来自 2019 年全球疾病负担研究的系统分析。柳叶刀健康长寿。2021,2, e580–e592.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 傅,R.;冯彦;刘燕;Yang, H. 牵张成骨过程中骨再生的机械调节。11月, 技术设备 2021,11, 100077.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 傅,R.;伯特兰;王军;卡瓦塞里;冯彦;杜彤;刘燕;威利;杨华.体内和计算机监测小鼠股骨牵张骨形成过程中的骨再生。计算。方法程序生物医学。2022,216, 106679.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 斯蒂夫勒,K.S.内部骨折固定。克林科技小动画实践。2004,19, 105–113.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 塔利亚诺维奇,理学硕士;琼斯,医学博士;露丝;本杰明;谢泼德;亨特,TB骨折固定。射线照相2003,23, 1569–1590.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 马纳姆;哈伦;史里,DNA;加尼;库尼亚万;伊斯梅尔;易卜拉欣,MHI植入物生物相容性金属腐蚀研究:综述。J. 合金公司2017,701, 698–715.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 哈西亚克;索别什赞斯卡,B.;拉什奇;比亚利;切克曼诺夫斯基;扎通斯基;波泽姆斯卡;与316L不锈钢和Ti6Al4V合金相比,ZrTi基块状金属玻璃的生产,机械性能和生物医学表征。材料2021,15, 252.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 伊特科拉;乔治亚州朗希塔诺;安图内斯,L.H.M.;贾迪尼;米格尔;贝雷斯;兰伯特;田纳西州安德拉德;布哈伊姆;布哈伊姆;等。增材制造生产的Co-Cr-Mo合金的骨整合改进。药剂学2021,13, 724.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 冈崎;Katsuda, S.I. 生物相容性 Ti-15Zr-4Nb 合金的生物安全性评估和表面改性。材料2021,14, 731.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 卡比尔;穆尼尔;温,C.;李玉.生物医学应用中可生物降解锌合金和复合材料的研究与进展:生物力学和生物腐蚀视角.生物行为。母校。2021,6, 836–879.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 王建林;徐建国;霍普金斯;周大华;可生物降解镁基植入物在骨科中的应用综述与展望.高级科学2020,7, 1902443.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 维特;北卡罗来纳州霍特;沃格特;科恩;凯纳;威勒米特;Feyerabend,F.基于镁腐蚀的可降解生物材料。库尔。奥平。固态母校。科学.2008,12, 63–72.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 张海英;申杰英;哦,S.H.;宾,J.H.;Lee,J.H. PCL/HA 杂交微球,用于有效的成骨分化和骨再生。ACS生物材料. 科学工程.2020,6, 5172–5180.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 杨燕;赵彦;唐国;李华;袁,X.;范荚。多孔聚(l-丙交酯-共-乙醇化物)/β-磷酸三钙(PLGA/β-TCP)支架在动态和静态条件下的体外降解。波利姆。退化。刺。2008,93,1838–1845.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 周华;劳伦斯;Bhaduri,S.B.用于骨科应用的PLA-CaP / PLGA-CaP复合材料的制造方面:综述。生物学报.2012,8, 1999–2016.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 张燕;徐军;阮,Y.C.;于明康;奥劳克林;怀斯,H.;陈丹;田玲玲;施德;王军;等。植入物衍生的镁诱导CGRP的局部神经元产生,以改善大鼠的骨折愈合。国家医学2016,22, 1160–1169.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 李,J.W.;韩旭;韩国强;帕克;全,H.;好的,先生;石,香港;安,JP;李,K.E.;李德华;等。镁合金体内生物降解机理的长期临床研究和多尺度分析.美国科学院院刊2016,113, 716–721.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 郑玉芳;顾新恩;维特,F.可生物降解金属。材料科学工程R代表2014,77,1–34。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 库马尔;吉尔;Batra,U.可生物降解镁合金植入物的挑战和机遇。母校技术。2017,33, 153–172.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 杨华;贾斌;张忠;曲,X.;李刚;林文;朱丹;戴克;可生物降解锌的合金化设计作为承重应用的有前途的骨植入物。国家公社。2020,11, 401.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 杨华;曲,X.;王敏;程华;贾斌;聂,J.;戴克;Zn-0.4Li合金在承重部位骨折的固定和愈合方面显示出巨大的潜力。化学工程J.2021,417, 129317.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 李刚;杨华;郑彦;陈晓华;杨杰;朱丹;阮,L.;使用锌及其合金作为可生物降解金属的挑战:从生物力学相容性的角度。生物学报.2019,97, 23–45.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 李华峰;施志忠;可生物降解锌基合金的机遇与挑战.J. 母校. 科学技术.2020,46, 136–138.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 托恩;拉尔森;诺林;Weissenrieder,J.盐溶液,血浆和全血中锌的降解。J. 生物医学。母校。B应用生物材料。2016,104, 1141–1151.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 安德烈尼;班慈;贝尔蒂尼;罗萨托,A.计算人类基因组中编码的锌蛋白。J. 蛋白质组研究2006,5, 196–201.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 魏斯;默多克;埃德蒙兹;约旦;蒙特斯;佩雷拉;罗德里格斯·纳西夫,上午;佩托莱蒂,上午;西弗吉尼亚州海狸;蒙内克;等。Zn调节的GTP酶金属蛋白激活剂1调节脊椎动物锌稳态。单元格2022,185、2148–2163。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 乔文;潘,D.;郑彦;吴淑贤;刘晓;陈志;万敏;冯淑贞;张国昌;杨国强;等。二价金属阳离子刺激骨骼内感受,形成小鼠损伤模型中的新骨。国家公社。2022,13, 535.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 朱丹;科克里尔;苏轩;张忠;傅建军;李国华;马军;奥克波克瓦西里;唐立;郑彦;等。Zn生物材料的机械强度,生物降解以及体外和体内生物相容性。ACS应用材料。接口 2019,11,6809–6819。[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 张忠;贾斌;杨华;韩彦;吴琦;戴克;可生物降解的ZnLiCa三元合金用于承重部位临界尺寸的骨缺损再生:体外和体内研究。生物行为。母校。2021,6, 3999–4013.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 鲍文;塞茨,J.M.;吉洛里;布雷科维奇,JP;赵淑贞;戈德曼;Drelich,J.W.通过支架应用的机械和体内测试评估锻造锌铝合金(1;3;和5wt %Al)。J. 生物医学。母校。B应用生物材料。2018,106, 245–258.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 丹巴塔,理学硕士;伊兹曼;库尼亚万;Hermawan,H.通过等通道角压加工Zn-3Mg合金,用于可生物降解的金属植入物。J. 沙特国王大学科学2017,29, 455–461.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 贾斌;杨华;张忠;曲,X.;贾旭;吴琦;韩彦;郑彦;用于大鼠股骨髁缺损模型中骨再生的可生物降解Zn-Sr合金:体外和体内研究。生物行为。母校。2021,6, 1588–1604.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 卡弗里;奥瓦迪亚;戈德曼;德雷利奇;阿吉翁,E.Zn–1.3%Fe合金作为可生物降解植入材料的适用性。金属2018,8, 153.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 克雷泽尔;马雷特,W.锌离子的生物无机化学。生化拱门。生物物理学。2016,611, 3–19.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 任涛;高晓松;徐春;杨林;郭平;刘华;陈彦;孙文;用于生物医学植入材料的挤压三元Zn-Mg-Zr合金的评估:体外和体内行为。母校。腐蚀。2019,70, 1056–1070.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 施志忠;于杰;刘晓峰;张海军;张德华;尹永闽;Ag、Cu或Ca添加对可生物降解Zn-0.8Mn合金组织和综合性能的影响.母校 工程 C 母校 生物 应用2019,99, 969–978.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 施志;于杰;微合金化Zn-Mn合金:在室温下从极脆到极强延展性。母校德斯。2018,144, 343–352.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 帅;程彦;杨燕;彭淑贤;杨文;用于骨修复的Zn-2Al部件的激光增材制造:可成形性;微观结构和性能。J. 合金公司2019,798, 606–615.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 帅;薛璐;高;彭淑贤;可生物降解Zn-Al-Sn合金中的棒状共晶结构表现出增强的机械强度。ACS生物材料. 科学工程.2020,6, 3821–3831.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 帅;薛璐;高;杨燕;彭淑贤;Zn-Ag合金的选择性激光熔化用于骨修复:微观结构;机械性能和降解行为。虚拟物理原型。2018,13, 146–154.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 施志;于杰;刘晓;新型可生物降解锌-锰-铜合金的制备与表征.J. 母校. 科学技术.2018,34, 1008–1015.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 肖春;王林;任轩;太阳;张磊;闫春;刘琦;太阳,X.;寿枫;段杰;等。间接挤压可生物降解的Zn-0.05wt%Mg合金,具有更高的强度和延展性:体外和体内研究。J. 母校. 科学技术.2018,34, 1618–1627.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 袁文;夏,D.;吴淑贤;郑彦;关志;劳,J.V.锌基生物降解金属表面改性研究现状.生物行为。母校。2022,7, 192–216.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 陈克;卢彦;唐华;高彦;赵芳;顾晓;应变对WE43,Fe和Zn线降解行为的影响。生物学报.2020,113, 627–645.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 杨杰;严,C.D.;溶质锌对NaCl溶液中形成的Mg-Sn-Zn合金腐蚀膜的影响。电化学2016,163,C839–C844。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 库巴斯克;沃伊特克;雅布隆斯卡;波斯皮西洛娃,I.;利波夫;瘤,T.结构,机械特性和体外降解;细胞 毒性;新型可生物降解Zn-Mg合金的遗传毒性和致突变性。母校 工程 C 母校 生物 应用2016,58, 24–35.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 李华峰;谢晓华;郑玉芳;丛,Y.;周凤凰;邱国军;王旭;陈淑贤;黄林;田玲玲;等。含有营养合金元素Mg,Ca和Sr.Sci的可生物降解Zn-1X二元合金的开发,Rep.2015,5,10719。[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 佟,X.;张丹;张鑫;苏轩;施志;王康;林俊杰;李燕;林俊杰;Wen, C. 显微结构;机械性能;生物相容性;以及用于可生物降解植入材料的新型Zn-5Ge合金的体外腐蚀和降解行为。生物学报.2018,82, 197–204.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 李平;张文;戴杰;Xepapadeas, A.B.;施韦泽;亚历山大;谢德勒;周春;张华;万国;等。锌铜合金作为颅颌面骨合成植入物潜在材料的研究。母校 工程 C 母校 生物 应用2019,103, 109826.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 瓦特罗巴;贝德纳奇克;卡瓦乌科;Bała, P. 锆微量加成对Zn-Zr合金组织和力学性能的影响.母校。查拉特。2018,142, 187–194.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 杨华;曲,X.;林文;王春;朱丹;戴克;郑轩锌-羟基磷灰石复合材料作为用于骨科应用的新型可生物降解金属基复合材料的体外和体内研究。生物学报.2018,71, 200–214.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 潘,C.;太阳,X.;徐国;苏轩;刘丹.β-TCP对机械性能的影响;β-TCP/Zn-镁复合材料的腐蚀行为和生物相容性。母校 工程 C 母校 生物 应用2020,108, 110397.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 李晓;朱春;Chu, P.K. 外部应力对可生物降解骨科材料的影响:综述。生物行为。母校。2016,1, 77–84.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 李,N.;用于生物医学应用的新型镁合金研究进展.J. 母校. 科学技术.2013,29, 489–502.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- Kirkland, N.T.; Birbilis, N.; Staiger, M.P. Assessing the corrosion of biodegradable magnesium implants: A critical review of current methodologies and their limitations. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.N.; Zhu, S.M.; Nie, J.F.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Z. Investigating the stress corrosion cracking of a biodegradable Zn-0.8 wt%Li alloy in simulated body fluid. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Feng, X.; Jia, X.; Fan, Y. Influences of tensile load on in vitro degradation of an electrospun poly(L-lactide-co-glycolide) scaffold. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 2991–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Chu, Z.; Yao, J.; Feng, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y. The effects of tensile stress on degradation of biodegradable PLGA membranes: A quantitative study. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 124, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Gu, X.; Zhang, K.; Xia, J.; Fan, Y. Effect of stress on corrosion of high-purity magnesium in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2019, 83, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Gu, X.; Chu, Z.; Guo, M.; Fan, Y. A quantitative study on magnesium alloy stent biodegradation. J. Biomech. 2018, 74, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, A.K.; Sadananda, K. Classification of environmentally assisted fatigue crack growth behavior. Int. J. Fatigue 2009, 31, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Singh Raman, R.K.; Davies, C.H.J. Corrosion fatigue of a magnesium alloy in modified simulated body fluid. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015, 137, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Gao, L.L.; Gao, H.; Yuan, X.; Chen, X. Biodegradable behaviour and fatigue life of ZEK100 magnesium alloy in simulated physiological environment. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2015, 38, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Gao, X.; Liu, X. Microstructure evolution of a high-strength low-alloy Zn–Mn–Ca alloy through casting; hot extrusion and warm caliber rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 771, 138626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Linsley, C.S.; Pan, S.; Yao, G.; Wu, B.M.; Levi, D.S.; Li, X. Zn-Mg-WC nanocomposites for bioresorbable cardiovascular stents: Microstructure, mechanical properties, fatigue, shelf life, and corrosion. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Yang, H.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, K. In vitro and in vivo studies of Zn-Mn biodegradable metals designed for orthopedic applications. Acta Biomater. 2020, 108, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katarivas Levy, G.; Leon, A.; Kafri, A.; Ventura, Y.; Drelich, J.W.; Goldman, J.; Vago, R.; Aghion, E. Evaluation of biodegradable Zn-1%Mg and Zn-1%Mg-0.5%Ca alloys for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Ge, Q.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, A.; Mu, Y. Mechanical characteristics and in vitro degradation of biodegradable Zn-Al alloy. Mater. Lett. 2021, 300, 130181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Niu, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Pei, J.; Ou, J.; Yuan, G. Potential biodegradable Zn-Cu binary alloys developed for cardiovascular implant applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 72, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Tong, X.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Wei, A.; Jin, L.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; et al. A biodegradable Zn-1Cu-0.1Ti alloy with antibacterial properties for orthopedic applications. Acta Biomater. 2020, 106, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, C.; Li, G.; Zheng, Y.; Nie, J. Creep properties of biodegradable Zn-0.1Li alloy at human body temperature: Implications for its durability as stents. Mater. Res. Lett. 2019, 7, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Xia, D.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Li, B.; Han, Y.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, D.; Ruan, L.; et al. Controllable biodegradation and enhanced osseointegration of ZrO2-nanofilm coated Zn-Li alloy: In vitro and in vivo studies. Acta Biomater. 2020, 105, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Qiu, K.; Wang, X. Design and characterizations of novel biodegradable ternary Zn-based alloys with IIA nutrient alloying elements Mg, Ca and Sr. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Tong, X.; Sun, Q.; Luan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, Z.; Wang, K.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Dargusch, M.; et al. Biodegradable ternary Zn-3Ge-0.5X (X = Cu; Mg; and Fe) alloys for orthopedic applications. Acta Biomater. 2020, 115, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaed, E.; Sikora-Jasinska, M.; Ardakani, M.S.; Mostaed, A.; Reaney, I.M.; Goldman, J.; Drelich, J.W. Towards revealing key factors in mechanical instability of bioabsorbable Zn-based alloys for intended vascular stenting. Acta Biomater. 2020, 105, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Ma, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Shi, G.; Wang, K.; Zhang, K. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and in vitro corrosion behavior of biodegradable Zn-1Fe-xMg alloy. Materials 2020, 13, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, P.K.; Shearier, E.R.; Zhao, S.; Guillory II, R.J.; Zhao, F.; Goldman, J.; Drelich, J.W. Biodegradable metals for cardiovascular stents: From clinical concerns to recent Zn-alloys. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 1121–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plum, L.M.; Rink, L.; Haase, H. The essential toxin: Impact of zinc on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2010, 7, 1342–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J.P.; Kanjilal, D.; Teitelbaum, M.; Lin, S.S.; Cottrell, J.A. Zinc as a therapeutic agent in bone regeneration. Materials 2020, 13, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapiero, H.; Tew, K.D. Trace elements in human physiology and pathology: Zinc and metallothioneins. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2003, 57, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glutsch, V.; Hamm, H.; Goebeler, M. Zinc and skin: An update. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2019, 17, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.; Abradelo, C.; San Roman, J.; Rojo, L. Bibliographic review on the state of the art of strontium and zinc based regenerative therapies. Recent developments and clinical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 1974–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Escobar, D.; Champagne, S.; Yilmazer, H.; Dikici, B.; Boehlert, C.J.; Hermawan, H. Current status and perspectives of zinc-based absorbable alloys for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater. 2019, 97, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezuela, J.; Dargusch, M.S. The influence of alloying and fabrication techniques on the mechanical properties, biodegradability and biocompatibility of zinc: A comprehensive review. Acta Biomater. 2019, 87, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hamzah, E.; Low, H.T.; Kasiri-Asgarani, M.; Farahany, S.; Akbari, E.; Cho, M.H. Fabrication of biodegradable Zn-Al-Mg alloy: Mechanical properties, corrosion behavior, cytotoxicity and antibacterial activities. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 73, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhodub, L.B. Antimicrobial activity of Ag, Cu+2+, Zn2+, Mg2+ ions doped chitosan nanoparticles. Ann. Mechnikov’s Inst. 2015, 1, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Aroca, A.; Cano-Vicent, A.; Sabater, I.S.R.; El-Tanani, M.; Aljabali, A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Mishra, Y.K. Scaffolds in the microbial resistant era: Fabrication, materials, properties and tissue engineering applications. Mater Today Bio 2022, 16, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riduan, S.N.; Zhang, Y. Recent Advances of Zinc-based Antimicrobial Materials. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 2588–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, C.O.; de Oliveira, A.L.M.; Chantelle, L.; Silva Filho, E.C.; Jaber, M.; Fonseca, M.G. Zn-doped mesoporous hydroxyapatites and their antimicrobial properties. Colloids Surf. 2021, 198, 111471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Shi, Z.; Xu, L.; Lin, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. Degradation behavior, cytotoxicity, hemolysis, and antibacterial properties of electro-deposited Zn-Cu metal foams as potential biodegradable bone implants. Acta Biomater. 2020, 102, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Yang, K. Antibacterial design for metal implants. In Metallic Foam Bone; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, D.; Wang, W. Microstructure; mechanical, corrosion properties and cytotoxicity of betacalcium polyphosphate reinforced ZK61 magnesium alloy composite by spark plasma sintering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 99, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shao, X.; Dai, T.; Xu, F.; Zhou, J.G.; Qu, G.; Tian, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y. In vivo study of the efficacy, biosafety, and degradation of a zinc alloy osteosynthesis system. Acta Biomater. 2019, 92, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, T.; Lopez, M.J. An overview of de novo bone generation in animal models. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]