The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic sedimentary rock that is found in the western United States, which has a wide assortment of taxa represented in its fossil record, including dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandstone, siltstone and limestone and is light grey, greenish gray, or red. Most of the fossils occur in the green siltstone beds and lower sandstones, relics of the rivers and floodplains of the Jurassic period. (mostly from Foster ; the higher-level classifications will vary as new finds are made.

- siltstone

- sedimentary rock

- sandstone

1. Amphibians

According to museum curator John Foster, "frogs are known from several sites in the Morrison Formation but are not particularly well represented."[1] The history of Morrison anuran discoveries began with the recovery of remains from Reed's Quarry 9 near Como Bluff Wyoming. The new genus Eobatrachus was erected for some of these remains by O. C. Marsh, but the material was later considered non-diagnostic. Decades later another dubious anuran genus, Comobatrachus was erected for addition fragmentary remains. Despite the erection of multiple new names, scientists only recognize two legitimate frog species from the Morrison, Enneabatrachus hechti[2] and Rhadinosteus parvus.[3]

In addition to formally named taxa, indeterminate anuran remains have been retrieved from Morrison strata in Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah, with the best specimens found in Dinosaur National Monument and Quarry 9.[1] Stratigraphically speaking, indeterminate anurans have been found in stratigraphic zones 2 and 4.[4] Indeterminate anurans with remains diagnostic down to the family level have also been reported from the Morrison. Pelobatids are represented by the illium of an unnamed, indeterminate species.[5] A specimen has been recovered from Quarry 9 of Como Bluff in Wyoming.[5] Pelobatids are present in stratigraphic zones 5 and 6.[4]

Indeterminate salamander remains are present in stratigraphic zones 2, 4, and 5.[4] A distinctive type of salamander known only as Caudata B is present in stratigraphic zone 6.[4]

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Comobatrachus[1] |

C. aenigmaticus |

|

A dubious genus of prehistoric frog erected by O. C. Marsh to house fragmentary remains recovered from Reed's Quarry 9 near Como Bluff Wyoming.[1] Along with Eobatrachus it was among the earliest frog remains from the formation, although the two dubious genera were erected decades apart.[1] |

||

|

Comonecturoides[6] |

C. marshi[6] |

|

Represented by a single femur.[6] |

Considered a nomen dubium because the name is based on non-distinctive remains which cannot be classified in detail.[6] |

|

|

Enneabatrachus[7] |

E. hechti[2] |

A small discoglossid frog whose live weight would have only been a few grams.[2] |

|||

|

Eobatrachus[1] |

E. agilis |

|

A dubious genus of prehistoric frog erected by O. C. Marsh to house fragmentary remains recovered from Reed's Quarry 9 near Como Bluff Wyoming.[1] Along with Comobatrachus it was among the earliest frog remains from the formation, although the two dubious genera were erected decades apart.[1] |

||

|

Iridotriton[7] |

I. hechti |

A basal salamandroid closely related to today's advanced salamanders. |

|||

|

Rhadinosteus[7] |

R. parvus[3] |

|

Known from several slabs of rock which contain multiple partial specimens in association.[3] |

A pipoid and possible rhinophrynid, Rhadinosteus parvus was only about 42 mm (1.6 inches) long in life.[3] |

2. Arthropods

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parapleurites[9] | P. morrisonensis |

|

a forewing. | a grasshopper. | |

|

Tektonargus |

T. kollaspilus |

|

|

Five specimens were reported in the original description of the ichnogenus. |

3. Choristoderes

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cteniogenys[7] |

C. antiquus |

|

A champsosaur about 25 to 50 cm in length. |

4. Crurotarsans

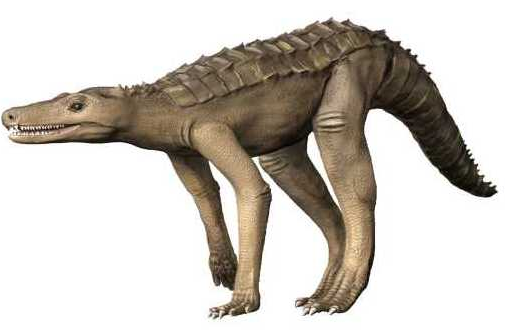

Crocodiles of a variety of sizes and habitats were common Morrison animals. Cursorial mesosuchians, or small terrestrial running crocs, included Hallopus victor and Fruitachampsa callisoni. More derived crocodilians included Diplosaurus ferox, Amphicotylus, Hoplosuchus kayi, and Macelognathus vagans.

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amphicotylus[10] |

A. gilmorei |

|

||||

|

A. lucasii |

|

|||||

|

A. stovalli |

|

|||||

|

Diplosaurus[11] |

D. felix |

|

||||

|

Eutretauranosuchus[7] |

E. delfsi |

|

||||

|

Fruitachampsa[7] |

F. callisoni |

|

|

|||

|

Hallopus[7] |

H. victor |

|

||||

|

Hatcherichnus |

H. sanjuanensis |

|

||||

|

Indeterminate |

|

|

||||

|

Hoplosuchus[7] |

H. kayi |

|

||||

|

Macelognathus[7] |

M. vagans |

|

||||

|

Theriosuchus[12] |

T. morrisonensis |

|

A nearly complete left mandible missing teeth. |

5. Fish

Although the paleoclimate of the Morrison formation was semiarid with only seasonal rainfall, there were enough bodies of water to support a diverse ichthyofauna.[13] Although abundant, fish remains are constrained to only certain locations within the formation.[13] Microvertebrate sites in Wyoming are dominated by fish remains.[13] Indeterminate ray-finned fish remains have been recovered from Ninemile Hill and a microvertebrate site in the Black Hills.[13] Found in stratigraphic zones 2, 4, and 5.[4] Morrison actinopterygians generally have no close modern relatives.[13] The Wyoming microvertebrate remains are extracted from the sediment by screenwashing.[13] Paleoniscoid remains are geographically present in the western part of Colorado, where remains have been recovered from "a level above the Mygatt-Moore Quarry."[13] Largely complete remains of small individuals have been consistently recovered for over 15 years.[13] So far, Morrison pycnodontoids are represented by a single specimen from Dinosaur National Monument in Utah.[14] Found in stratigraphic zone 4.[4] Only a single specimen from Dinosaur National Monument in Utah has been recovered.[14] Pycnodontoids were "deep-bodied and laterally compressed fish" whose tooth morphology suggest that they preyed on small contemporary invertebrates. They may have resembled modern butterfly fish.[14] A single tooth is the only known remains.[14] Dipnoan remains found at a fossil site not far from Cañon City, Colorado.[13] Remains usually in a state of rather complete preservation.[13] Halecostome remains are geographically present in the western part of Colorado, where remains have been recovered from "a level above the Mygatt-Moore Quarry."[13] Largely complete remains of small individuals have been consistently recovered for over 15 years.[13] Amiid remains found in stratigraphic zones 2, 3, and 4.[4] Found at a fossil site not far from Cañon City, Colorado.[13] Remains usually in a state of rather complete preservation.[13]

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ceratodus[7] |

C. fossanovum[13] |

A lungfish genus whose members ranged from 1 to 2 m in length and weights of up to 79 pounds, with most Morrison lungfish being on the smaller end of that range.[13] These species are believed to have had similar diets to extant lungfish like the physically similar modern genus Neoceratodus.[13] |

||||

|

C. ?frazieri[13] |

||||||

|

C. guentheri[13] |

||||||

|

C. robustus[13] |

||||||

|

Indeterminate. |

|

Represented by tooth plates. |

||||

|

Hulettia[7] |

H. hawesi[15] |

|

A small fish of the division Halecostomi about 7.6 cm in length and 5g of live mass which probably preferred quiet water. Its fossils prominently preserve its thick interlocking scales. |

|||

|

cf. Leptolepis[7] |

N/A |

|

Known only from a single nearly complete skeleton found at Rabbit Valley.[16] Found in stratigraphic zone 5.[4] |

A 13 cm (5 inch) fish that was deeper bodied than its co-occurring contemporaries Morrolepis and Hulettia.[16] The Morrison cf. Leptolepis probably had a live mass of about 37g.[16] It is the only teleost fish known from the formation and was morphologically more highly derived than other Morrison fish.[16] It is believed to have fed on contemporary fish and small invertebrates.[16] |

||

|

Morrolepis[7] |

M. schaefferi[17] |

|

A palaeoniscoid with forward-set eyes positioned past the front end of the lower jaw. It had a tall dorsal fin set far back on the body and an asymmetrical caudal fin.[17] Adult specimens would reach about 20 cm in length and 113 g (4 oz) in mass.[17] |

|||

|

Potamoceratodus |

P. guentheri |

|

Once thought to be a species of Ceratodus. |

6. Lizards and Snakes

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diablophis[18] |

D. gilmorei |

|

A basal snake.[18] Originally described as a species of Parviraptor,[7] subsequently moved to its own genus.[18] |

||

|

Dorsetisaurus[7] |

|

An anguimorph lizard. |

|||

|

Paramacellodus[7] |

|

A small scincomorph lizard with blunt teeth. |

|||

|

Saurillodon[7] |

Indeterminate |

|

A scincomorph lizard whose remains have been found in Middle Jurassic strata in England and Scotland as well as Late Jurassic strata in Portugal in addition to the Morrison formation remains.[19] |

||

|

S. utahensis[21] |

|

A small scincomorph lizard of otherwise uncertain evolutionary affinities.[21] It is the only lizard genus endemic to the Morrison Formation.[21] |

7. Mammaliaforms

Many types of mammaliaform cynodonts, mostly early mammals, are known from the Morrison; almost all of them were small sized animals, though occupying a very large variety of ecological niches, from the more rodent-like multituberculates to the carnivorous eutriconodonts (including the possibly volant Triconolestes) to the anteater-like Fruitafossor. Unclassified types include the digger Fruitafossor windscheffelia. Docodonts included the common genus Docodon, represented by D. victor, D. striatus, and D. superbus, and Peraiocynodon sp. Multituberculates, a common type of early mammal, were represented by Ctenacodon serratus, C. laticeps, C. scindens, Glirodon grandis, Morrisonodon brentbaatar, Psalodon fortis, ?P. marshi, P. potens, and Zofiabaatar pulcher. Triconodonts present included Amphidon superstes, Aploconodon comoensis, Conodon gidleyi, Priacodon ferox, P. fruitaensis, P. gradaevus, P. lulli, P. robustus, Triconolestes curvicuspis, and Trioracodon bisulcus.

Tinodontids were represented by Eurylambia aequicrurius (probably Tinodon), and Tinodon bellus (including T. lepidus). Finally, two families of Dryolestoidea were present: Paurodontidae, including Comotherium richi, Euthlastus cordiformis, Paurodon valens, and Tathiodon agilis; and Dryolestidae, including Amblotherium gracilis, Dryolestes obtusus (common genus), D. priscus, D. vorax, Laolestes eminens, L. grandis, and Miccylotyrans minimus.

In 2009, a study by J. R. Foster was published which estimated the body masses of mammals from the Morrison Formation by using the ratio of dentary length to body mass of modern marsupials as a reference. Foster concludes that Docodon was the most massive mammaliaform genus of the formation at 141g and Fruitafossor was the least massive at 6g. The average Morrison mammal had a mass of 48.5g. A graph of the body mass distribution of Morrison mammal genera produced a right-skewed curve, meaning that there were more low-mass genera.[22]

7.1. Tinodontids

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eurylambia |

E. aequicrurius |

|

A tinodontid similar in appearance to Tinodon. |

||

|

Tinodon[7] |

T. bellus |

|

Tinodontids. |

||

|

T. lepidus |

|

7.2. Eutriconodonts

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amphidon[7] |

A. superstes |

|

A small amphidontid. |

||

|

Aploconodon[7] |

A. comoensis |

|

An amphilestid eutriconodont. |

||

|

Comodon[7] |

C. gidleyi |

|

An amphilestid eutriconodont slightly larger in size than Aploconodon. |

||

|

Phascalodon |

P. gidleyi |

|

|||

|

Triconolestes[7] |

T. curvicuspis |

|

A volaticotherian eutriconodont. |

||

|

Trioracodon[7] |

T. bisulcus |

|

A triconodontid eutriconodont similar to Priacodon. |

7.3. Multituberculates

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ctenacodon[7] |

C. laticeps |

|

|||

|

C. scindens |

|||||

|

C. serratus |

|

||||

|

Glirodon[7] |

G. grandis |

|

|||

|

Morrisonodon |

M. brentbaatar |

|

|||

|

Priacodon[7] |

P. ferox |

|

|||

|

P. fruitaensis |

|

||||

|

P. grandaevus |

|

||||

|

P. lulli |

|

||||

|

P. robustus |

|

||||

|

Psalodon[7] |

P. fortis |

||||

|

P. marshi |

|||||

|

P. potens |

|||||

|

Zofiabaatar[7] |

Z. pulcher |

|

7.4. Others

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Docodon[7] |

D. victor[23] |

||||

|

Fruitafossor[7] |

F. windscheffeli |

|

7.5. Dryolestoids

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amblotherium[7] |

A. gracilis |

|

A small Dryolestid dryolestoid. |

||

|

Araeodon[7] |

A. intermissus |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid, somewhat smaller than Archaeotrigon and Paurodon. Considered to be a junior synonym of Paurodon valens by Averianov and Martin (2015).[24] |

||

|

Archaeotrigon[7] |

A. brevimaxillus |

|

Paurodontid dryolestoids similar in appearance to Paurodon. Both species were considered to be junior synonyms of Paurodon valens by Averianov and Martin (2015).[24] |

||

|

A. distagmus |

|||||

|

Comotherium[7] |

C. richi |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid. |

||

|

Dryolestes[7] |

D. obtusus |

Dryolestid dryolestoids. |

|||

|

D. priscus |

|

||||

|

D. tenax |

|||||

|

Euthlastus[7] |

E. cordiformis |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid. |

||

|

Foxraptor[7] |

F. atrox |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid similar in size to Paurodon. Considered to be a junior synonym of Paurodon valens by Averianov and Martin (2015).[24] |

||

|

Herpetairus |

H. |

||||

|

Kepolestes |

K. |

|

|||

|

Laolestes[7] |

L. eminens |

Common Dryolestid dryolestoids. |

|||

|

L. grandis |

|||||

|

Malthacolestes |

M. |

||||

|

Melanodon |

M. |

||||

|

Miccylotyrans |

M. minimus |

|

A Dryolestid dryolestoid. |

||

|

Paurodon[7] |

P. valens |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid. |

||

|

Pelicopsis |

P. dubius |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid. Considered to be a junior synonym of Paurodon valens by Averianov and Martin (2015).[24] |

||

|

Tathiodon[7] |

T. agilis |

|

A paurodontid dryolestoid. |

8. Pterosaurs

Pterosaurs are very uncommon fossils in the Morrison, because the fragility of their thin walled bones often prevented their remains from being preserved.[25] Despite being uncommon they are geographically widespread;[26] indeterminate pterosaur remains have been found in stratigraphic zones 2 and 4-6.[4] In addition to indeterminate remains, several species have been identified from both the rhamphorhynchoids (long-tailed pterosaurs) and pterodactyloids (short-tailed pterosaurs).[25] Since the 1970s and 80s, pterosaur finds have become more common, but are still rare.[25] Most Morrison pterosaurs have been found in marine and shoreline deposits.[25] Pterosaur tracks have been found in both the Tidwell and Saltwash members.[25] Morrison pterosaurs probably lived on fish, insects and scavenged dinosaur carcasses, or even foraged for prey,and activally hunted;[25] they are fairly ecologically diverse, ranging from small hawking insectivore Mesadactylus to the raptorial Harpactognathus.

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Comodactylus[7] |

C. ostromi |

|

|

1 specimen. |

Nomen dubium |

|

Dermodactylus[7] |

D. montanus |

|

|

1 specimen. |

Nomen dubium |

|

Harpactognathus[7] |

H. gentryii |

|

|

1 specimen. |

A large rhamphorhynchoid with a wingspan of about 2.5 m and live mass of about 1.5 kg (3.3 lbs).[27] Harpactognathus was related to the Solnhofen genus Scaphognathus.[27] |

|

Kepodactylus[7] |

K. insperatus |

|

|

1 specimen. |

A large pterodactyloid with a 2.5 m (8 foot) wingspan and a live weight of about 1.5 kg (3 lbs).[28] Kepodactylus may be related to the Asian dsungaripteroid pterosaurs.[28] |

|

Laopteryx[26] |

L. priscus |

|

|

1 specimen. |

Nomen dubium initially misidentified as a bird. |

|

Mesadactylus[7] |

M. ornithosphyos |

|

|

||

|

Pteraichnus[29] |

P. saltwashensis'* |

|

|

||

|

Utahdactylus[7] |

U. kateae |

|

|

1 specimen. |

Nomen dubium. All that can be said for certain about its identity is that it is a diapsid reptile. |

9. Sphenodonts

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Eilenodon[7] |

E. robustus |

|

A sphenodontian of relatively large size. |

||

|

Opisthias[7] |

O. rarus |

|

A sphenodontian similar in appearance to the modern Tuatara |

||

|

Theretairus[7] |

T. antiquus |

|

A small sphenodontian. |

10. Turtles

Turtles (Testudines) are very common fossils in the Morrison, due to their bony shells. The most common were Glyptops plicatus (very common) and Dinochelys whitei (also common, but not as common as Glyptops). Also present were Dorsetochelys buzzops and Uluops uluops.

| Name | Species | State | Member | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chelonipus |

|

|

|||

|

Compsemys |

C. plicatulus |

|

|||

|

Dinochelys[7] |

D. whitei |

|

|||

|

Dorsetochelys[7] |

D. buzzops |

||||

|

Glyptops[7] |

G. plicatulus |

|

|||

|

G. ornatus |

|

||||

|

G. utahensis |

|

||||

|

Uluops[7] |

U. uluops |

|

References

- Foster, J. (2007). "Anura (Frogs)." pp. 135-136.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Enneabatrachus hechti" p. 137.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Rhadinosteus parvus." p. 137.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Pelobatidae indet." p. 137.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Caudata (Salamanders)" p. 138.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Table 2.1: Fossil Vertebrates of the Morrison Formation." pp. 58-59.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Enneabatrachus hechti" p. 137. Note that Dinosaur National Monument is in Utah, see ibid. pg. 6.

- D. M. Smith, M. A. Gorman, J. D. Pardo and B. J. Small. 2011. First fossil Orthoptera from the Jurassic of North America. Journal of Paleontology 85(1):102-105

- Pritchard, A. C.; Turner, A. H.; Allen, E. R.; Norell, M. A. (2013). "Osteology of a North American Goniopholidid (Eutretauranosuchus delfsi) and Palate Evolution in Neosuchia". American Museum Novitates 3783 (3783): 1. doi:10.1206/3783.2. edit

- Allen, Eric Randall (Summer 2012). "Analysis of North American goniopholidid crocodyliforms in a phylogenetic context" (pdf). doi:10.17077/etd.317zy27t. http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3366&context=etd&sei-redir=1&referer=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2Furl%3Fsa%3Dt%26rct%3Dj%26q%3Ddiplosaurus%2520turner%26source%3Dweb%26cd%3D5%26ved%3D0CEsQFjAE%26url%3Dhttp%253A%252F%252Fir.uiowa.edu%252Fcgi%252Fviewcontent.cgi%253Farticle%253D3366%2526context%253Detd%26ei%3DQhMpU8TqC-ep2gXcyIH4Bw%26usg%3DAFQjCNHsB4dtBiKXySEHRnbcx6OkBDrTyw%26sig2%3DrP9S0ueLqMFp5yB3KBCGqw%26bvm%3Dbv.62922401%2Cd.b2I#search=%22diplosaurus%20turner%22.

- Foster, J. (2018). "A new atoposaurid crocodylomorph from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Wyoming, USA" (in en). Geology of the Intermountain West 5: 287–295. doi:10.31711/giw.v5i0.32. ISSN 2380-7601. https://www.utahgeology.org/giw/index.php/giw/article/view/32.

- Foster, J. (2007). "The Forgotten Aquatic Denizens: The Fish." pp. 129-131.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Pycnodontoidea." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. p. 135.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Hulettia hawesi." p. 132-134.

- Foster, J. (2007). "cf. Leptolepis." p. 135.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Morrolepis schaefferi." pp. 131-132.

- Caldwell, M. W.; Nydam, R. L.; Palci, A.; Apesteguía, S. N. (2015). "The oldest known snakes from the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous provide insights on snake evolution". Nature Communications 6: 5996. doi:10.1038/ncomms6996. PMID 25625704. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fncomms6996

- Foster, J. (2007). "Saurillodon sp." p. 145.

- Randall L. Lydam, Daniel J. Chure and Susan E. Evans (2013). "Schillerosaurus gen. nov., a replacement name for the lizard genus Schilleria Evans and Chure, 1999 a junior homonym of Schilleria Dahl, 1907". Zootaxa 3734 (1): 99–100. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3736.1.6. http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2013/f/zt03736p100.pdf.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Schilleria utahensis" p. 145.

- Foster, J.R. 2009. Preliminary body mass estimates for mammalian genera of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, North America). PaleoBios 28(3):114-122.

- Julia A. Schultz; Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar; Zhe-Xi Luo (2018). "Re-examination of the Jurassic mammaliaform Docodon victor by computed tomography and occlusal functional analysis". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. in press. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9418-5.

- A.O. Averianov and T. Martin (2015). "Ontogeny and taxonomy of Paurodon valens (Mammalia, Cladotheria) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of USA". Proceedings of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences 319 (3): 326–340. http://www.zin.ru/journals/trudyzin/doc/vol_319_3/TZ_319_3_Averyanov.pdf.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Soaring Overhead: The Pterosaurs." pp. 157-158.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Laopteryx priscus." p. 160.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Harpactognathus gentryii." p. 160.

- Foster, J. (2007). "Kepodactylus insperatus." p. 160.

- Lockley et al. (2008).