The

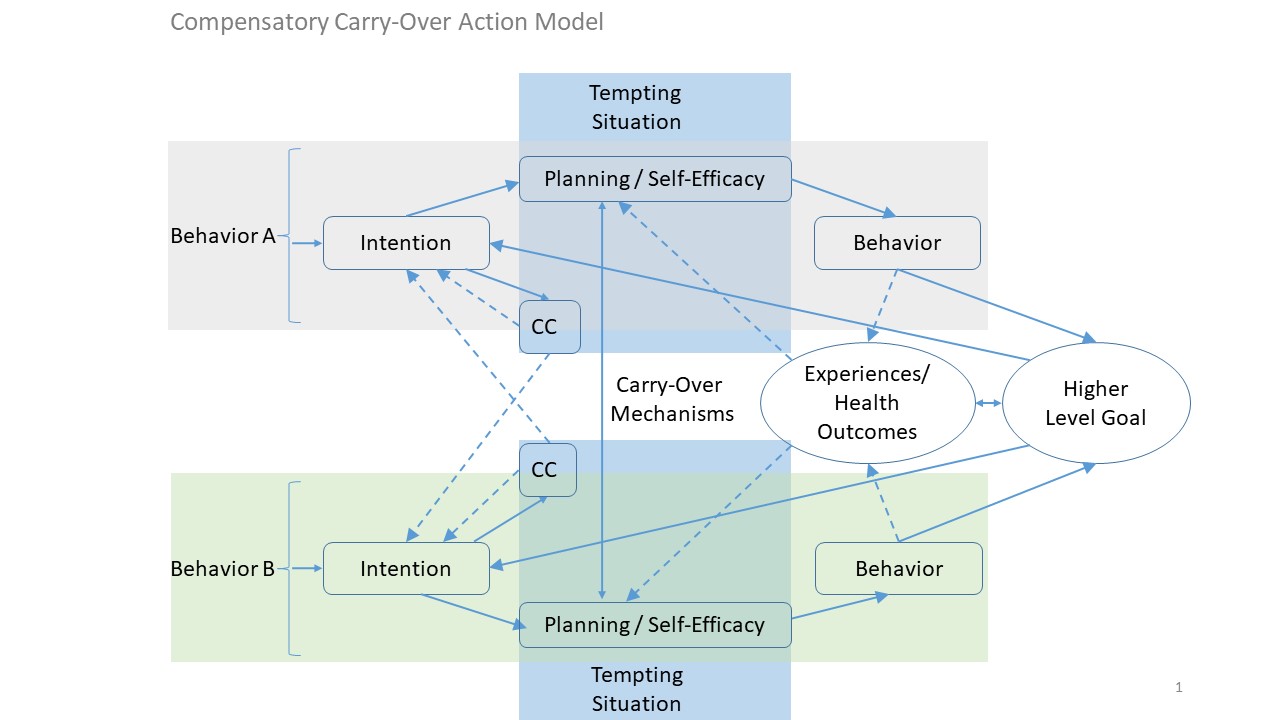

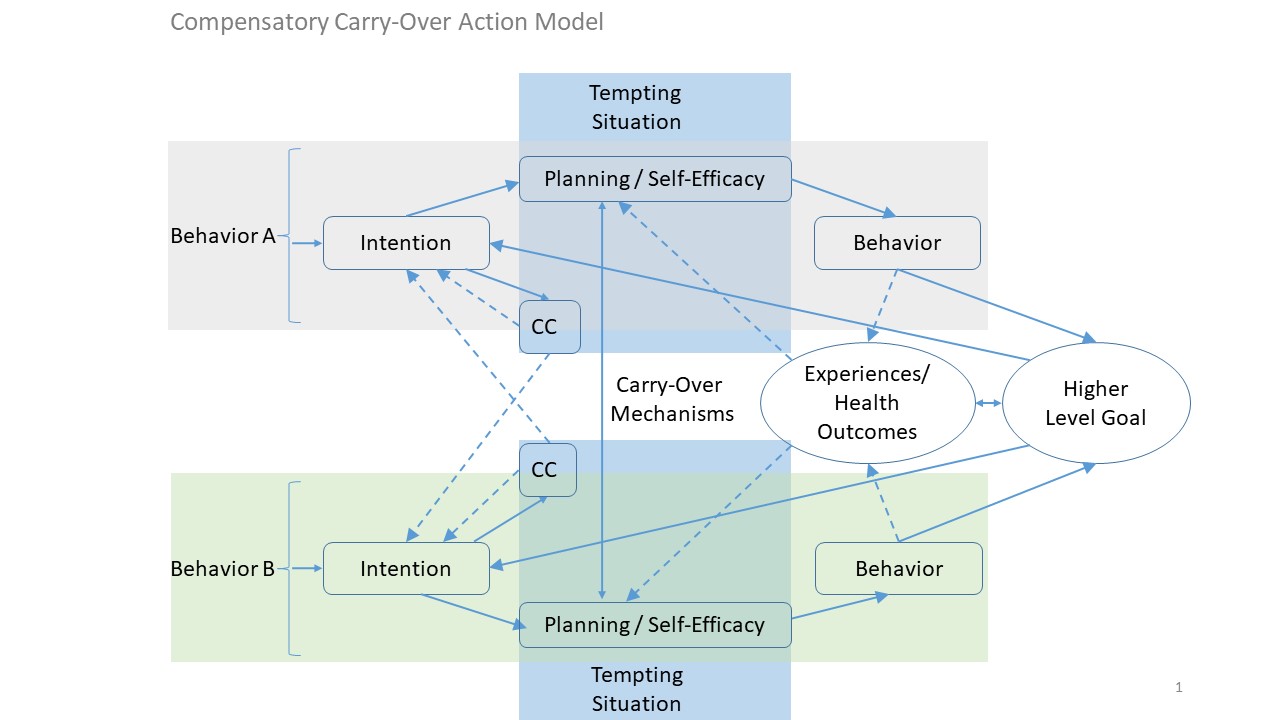

Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model

(CCAM) is innovative as most behavioral theories only model single activity. The CCAM, however, models different single activities—such as physical activity and Nutrition —and how they change as a result of one another. Such lifestyle activities are assumed to be formed by higher-level goals, which can drive activity volitionally or unconsciously, and are rather unspecific. They become specific because of activities that are subjectively seen as leading to this goal. Each activity must be intended, pursued, and controlled. Specific resources ensure that individuals have the chance to translate their intentions into activity, and that they resist distractors. Compensation and transfer (also called carry-over) operate between the different activities. If people devote all of their energy to one domain and believe that no resources remain for the other activity, compensation can help to attain goals. It is also possible that an individual successfully performs one activity, and existing or developing resources may be transferred to another activity.

- Multiple Behavior Change

- Physical Activity

- Physical Excerise

- Nutrition

- Health Behavior

- Work-Life Balance

Most goals in life (e.g., becoming a high performing scientist or/and staying healthy, a so-called higher-level-goal) can only be reached by means of more than one behavior (e.g., to exercise appropriately and also to detach from work adequately). As there are no other models explicitly explaining this, the CCAM is unique in terms of describing multiple (health) behaviors reciprocally. The CCAM is based on other models which assume that actions must be intended, planned, and translated into concrete behavior. Higher-level-goals can determine outcome expectancies, and thereby control the actions via goal setting. Compensatory cognitions start operating in case of tempting situation (e.g., having to work overtime): If behavior A (e.g., exercising appropriately after work) is hindered, one can decide to perform another behavior (behavior B; e.g., do active commuting). Alternatively, one can adapt performance of behavior A by either executing it later or in a different way (e.g., exercising the next morning or with a shorter duration).

Single studies support specific assumptions (see reference below). There is evidence that different behaviors interrelate. Different studies support the assumption that carry-over mechanisms exist, and showing that cognitive carry-over and behavioral outcomes depend on, for instance, whether physical activity resources are being transferred to nutrition behavior. Research is still needed, however, to extend assumptions of the CCAM. This needs to be done using different research designs, particularly longitudinal observations, Randomized Control Trials with experimentally testing effects, and complex analyses of different behaviors and how they change depending on each other.

-

Single studies support specific assumptions (see reference below). There is evidence that different behaviors interrelate. Different studies support the assumption that carry-over mechanisms exist, and showing that cognitive carry-over and behavioral outcomes depend on, for instance, whether physical activity resources are being transferred to nutrition behavior. Research is still needed, however, to extend assumptions of the CCAM. This needs to be done using different research designs, particularly longitudinal observations, Randomized Control Trials with experimentally testing effects, and complex analyses of different behaviors and how they change depending on each other.

References

Cihlar, V., & Lippke, S. (2017). Physical Activity Behavior and Competing Activities: Interrelations in 55-to 70-Year-Old Germans.

Journal of aging and physical activity

,

25

(4), 576-586.

Geller, K., Lippke, S., & Nigg, C. R. (2017). Future directions of multiple behavior change research.

Journal of behavioral medicine

,

40

(1), 194-202.

Liang, W., Duan, Y. P., Shang, B. R., Wang, Y. P., Hu, C., & Lippke, S. (2019). A web-based lifestyle intervention program for Chinese college students: study protocol and baseline characteristics of a randomized placebo-controlled trial.

BMC public health

,

19

(1), 1097.

Lippke, S. (2014). Modelling and supporting complex behavior change related to obesity and diabetes prevention and management with the Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model.

Journal of Diabetes & Obesity, 1

(2), 1-5.

https://www.ommegaonline.org/article-details/Modelling-and-Supporting-Complex-Behavior-Change-Related-to-Obesity-and-Diabetes-Prevention-and-Management-with-the-Compensatory-Carry-over-Action-Model/195

Lippke, S. (2019).

Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model.

In Hackfort, D., Schinke, R. J., & Strauss, B. (Eds.). Dictionary of sport psychology: sport, exercise, and performing arts (pp. 53). London, UK: Academic Press/Elsevier.

Lippke, S., & Cihlar, V. (2020). Social Participation during the Transition to Retirement: Findings on Work, Health and Physical Activity beyond Retirement from an Interview Study over the Course of 3 Years.

Activities, Adaptation & Aging

, 1-24.

Lippke, S., & Schüz, B. (2019). Modelle gesundheitsbezogenen Handelns und Verhaltensänderung. In

Gesundheitswissenschaften

(pp. 299-310). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Storm, V., Reinwand, D., Wienert, J., Kuhlmann, T., De Vries, H., & Lippke, S. (2017). Brief report: Compensatory health beliefs are negatively associated with intentions for regular fruit and vegetable consumption when self-efficacy is low.

Journal of health psychology

,

22

(8), 1094-1100.

Tan, S. L., Storm, V., Reinwand, D. A., Wienert, J., de Vries, H., & Lippke, S. (2018). Understanding the positive associations of sleep, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake as predictors of quality of life and subjective health across age groups: a theory based, cross-sectional web-based study.

Frontiers in psychology

,

9

, 977.

Tan, S. L., Whittal, A., & Lippke, S. (2018). Associations among Sleep, Diet, Quality of Life, and Subjective Health.

Health Behavior and Policy Review

,

5

(2), 46-58.