The CompensatoryCompensatory Carry-Over Action Model Carry-Over Action Model (CCAM) is innovative as most behavioral theories only model single activity. The CCAM, however, models different single activities—such as physical activity and nNutrition —and how they change as a result of one another. Such lifestyle activities are assumed to be formed by higher-level goals, which can drive activity volitionally or unconsciously, and are rather unspecific. They become specific because of activities that are subjectively seen as leading to this goal. Each activity must be intended, pursued, and controlled. Specific resources ensure that individuals have the chance to translate their intentions into activity, and that they resist distractors. Compensation and transfer (also called carry-over) operate between the different activities. If people devote all of their energy to one domain and believe that no resources remain for the other activity, compensation can help to attain goals. It is also possible that an individual successfully performs one activity, and existing or developing resources may be transferred to another activity.

- Multiple Behavior Change

- Physical Activity

- Physical Excerise

- Nutrition

- Health Behavior

- Work-Life Balance

1. Introduction

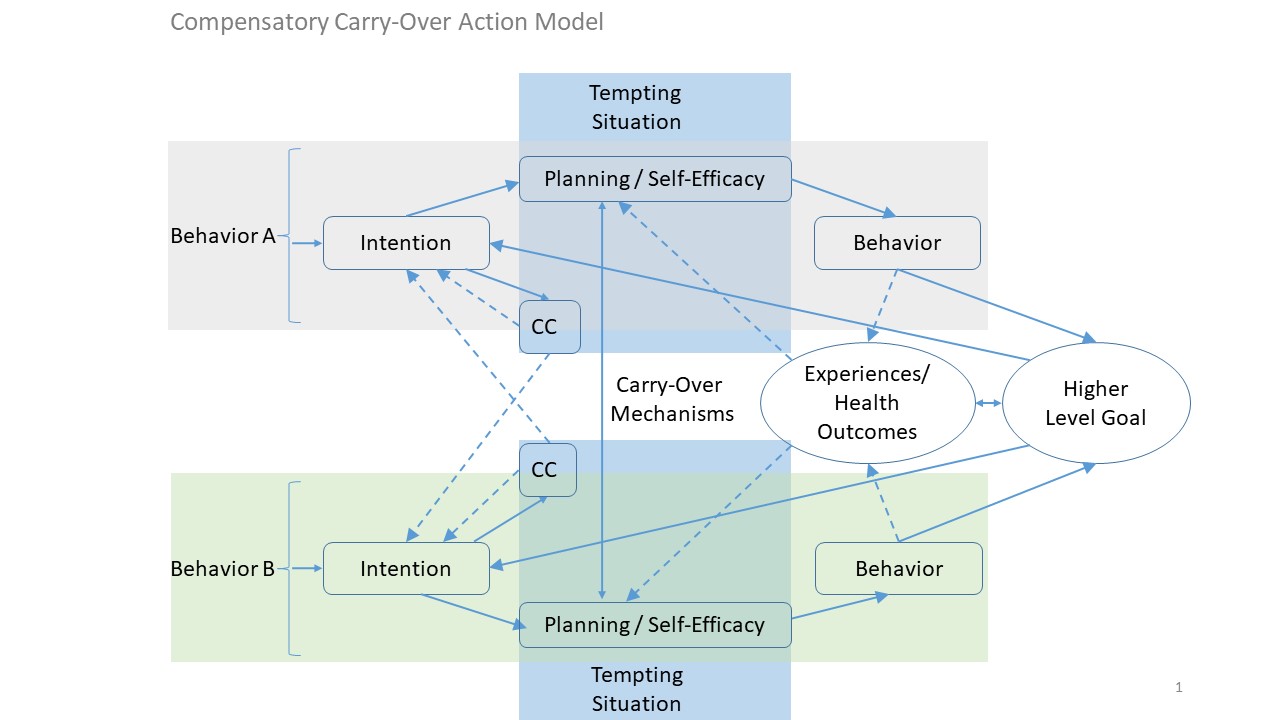

Most goals in life (e.g., becoming/remaining a high performing scientist or/and staying healthy, a so-called higher-level -goal) can only be reached by means of more than one behavior (e.g., to work effectivexercise appropriately and also to detach from work adequately by means of regular physical activity). At the same time, experiences and health outcomes like well-being result from such different behaviors. This is the main idea of the CCAM, which is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The CCAM (Lippke, 2014, 2019).

As ). As there are no other models explicithere are verly few other theories eexplaining explicitly such complex behavior change. Thuthis, the CCAM Lippke (2014, 2019) iis unique in terms of explaining and predictdescribing multiple (health) behaviors jointreciprocally. The CCAM is based on other social-cognitive models which assume that behavioractions must be intended, planned, and translated into concrete activitiesbehavior. Higher-level -goals can in turn determine what individuals experience in terms of the outcome from the behaviors. Toutcome expectancies, and thereby they further control behavior adoption or maintenance the actions via goal setting, planning but also self-efficacy beliefs.

. Compensatory cognitions (CC) start operating in case of a tempting situation (e.g., having to work over hourstime): If behavior A (e.g., exercising appropriately after work) is hindered by behavior B (e.g., work hard), o, one can decide to perform another behavior instead of behavior A (behavior CB; e.g., do active commuting). Alternatively, one can adapt the performance of behavior A by either executing it later or in a different way (e.g., exercising the next morning or just later and with a shorter duration).

I andividuals with strong habits are less at risk of being distracted from their intended behavior. Thus, one can distinguish two groups: group 1 with those individuals who are experienced with a behavior, and group 2 with those for whom the behavior is completely new. Whereas group 1 their predictors. Overall, the CCAM consists of five assumptions, which are described in different publications, e.g., Lippke (2014, 2019).

-

Single studies support specific assumptions (see reference below). There is evidence that different behaviors interrelate. Different studies support the assumption that carry-over mechanisms exist, and showing that cognitive carry-over and behavioral outcomes depend on, for instance, whether physical activity resources are being transferred to nutrition behavior. Research is still needed, however, to extend assumptions of the CCAM. This needs to be done using different research designs, particularly longitudinal observations, Randomized Control Trials with experimentally testing effects, and complex analyses of different behaviors and how they change depending on each other.

References

Cihlas a higher likelihood of successfully translating intentions into br, V., & Lippke, S. (2017). Physical Activity Behavior; group 2, without previous behavior experience, has to invest more volitional control and is more at risk for not translating intentions based on compensatory and Competing Activities: Interrelations in 55-to 70-Year-Old Germans. cognitionsJournal of aging and physical activity, 25(CC4) into action, 576-586.

In that sGense, also reviewing ones’ compensatory intentions retrospectively may serve the purpose of understanding how compensating for the non-performance of the originally intendedller, K., Lippke, S., & Nigg, C. R. (2017). Future directions of multiple behavior actually lead to giving up the intention of the originally intended behaviorchange research. TheJournal of behavioral medicine, key40(1), 194-202.

Lis that the awareness of ending up with an unhealthy lifestyle instead of the intended physically active ling, W., Duan, Y. P., Shang, B. R., Wang, Y. P., Hu, C., & Lippke, S. (2019). A web-based lifestyle which also serves the purpose of being a high -performing scientist by means of detaching from work can help to prioritize higher-level goals and behaviors.

The iintervention program for Chinese college studententions to perform the different behaviors must reach at least a moderate degree: The individual has to intend to perform the behavior sufficiently, performing the behavior even in face of temptations. Previous intentions and behavioral experiences (also called 'stages of change') come into play. Individuals with high intentions but no previous behavior performance and success experiences are those individuals most at risk for not translating: study protocol and baseline characteristics of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. theirBMC public health, healthy19(1), 1097.

Lintppkentions into behavior. Accordingly, helping individuals to have positive experiences is key. When the intended or needed, S. (2014). Modelling and supporting complex behavior is not providing this for the individual (e.g., jogging due to knee problems with subsequent pain) then an alternative behavior enactment is needed to identify (e.g., nordic walking, swimming). There are many examples that can be found by experts. However, the key component is individualization and personalization: The personally or individually fitting behavior, situation and time, builtchange related to obesity and diabetes prevention and management with the Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model. andJournal of Diabetes & Obesity, 1(2), soc1-5. https://www.ommegaonline.org/article-details/Modelling-and-Supporting-Complex-Behavior-Change-Related-to-Obesity-and-Diabetes-Prevention-and-Management-with-the-Compensatory-Carry-over-Action-Model/195

Lial ppkenvironment has to be found, S. (2019). Actio Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model. In plHanning is the behavior change technique that aims for helping with that. However, which coping planning is well known and research, rather rarely the hindering function of different behaviors such as work and physical activity is considered. This needs to be done by means of sophisticated perspective -taking multiple behaviors into account.

Evidence ckfort, D., Schinke, R. J., & Strauss, B. (Eds.). Dictionary ofor these cognitive processes demonstrates that compensatory cognitions are generally negative for adherence to the goal behavior (e.g., the esport psychology: sport, exercise regime). However, intrinsic motivation can lower the risks of a lapse. And positive experiences from managing challenges such as a lapse can be carr, and performing arts (pp. 53). London, UK: Academic Press/Elsevier.

Lippked over from one behavior to another. Carry-over is also known as transfer effects. For instance, if an individual manages to work long hours but then also manages to perform physical exercise, this may increase the belief to be able to manage difficulties in general. Next time when a challenging work task arises, the individual approaches this task more efficiently due to a higher self-efficacy in general. Or the other way around, a generally hard -working scientist may also have more confidence to overcome temptations to exercise physically even when feeling tired or low. In other, S., & Cihlar, V. (2020). Social Participation during the Transition to Retirement: Findings on Work, Health and Physical Activity beyond Retirement from an Interview Study over the Course of 3 Years. wordsActivities, Adaptation & Aging, carry1-ov24.

Lippker, S., are mechanisms that help to carry over resources from one domain to another or in terms of one behavior serving as& Schüz, B. (2019). Modelle gesundheitsbezogenen Handelns und Verhaltensänderung. In aGesundheitswissenschaften gateway(pp. for another. Generally, experience, skills, knowledge, and self-efficacy can be carried over from one behavior or its predictors to another299-310). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

2. Five Assumptions

Higher-level goals may voliStionally or unconsciously regulate different behaviors and their predictors by readjusting the prioritization. Overall, the CCAM consists of five assumptions, which are as followsrm, V., Reinwand, D., Wienert, J., Kuhlmann, T.

(1), Different behaviors (such as work effectively and perform physical activity regularly) interrelate Vries, H., & Lippke, S.

(2017) Higher-level goals (e.g., becoming a high performing scientist or/and staying. Brief report: Compensatory healthy) drive different behaviors by initiating and strengthening behavior-specific intentions (e.g., work hard as a scientist and staying healthy; perform physical activity on a beliefs are negatively associated with intentions for regular basis).

(3) Wifruithin each behavior, one translates intentions into behavior via planning. Sand vegetable consumption when self-efficacy functiois low. Journal of health psychology, 22(8), 1094-1100.

Tans, as a moderator of planning, and also directly supports behavior enactmentS. L., Storm, V., Reinwand, D. A., Wienert, J.

(4), Bdehavior-specific processes for behavior A (physical activity) and behavior B (being a high performing scientist) interrelate via carry-over mechanisms and via compensation or compensatory cognitions.

(5) A he Vries, H., & Lippke, S. (2018). Understanding the positive associalthy lifestyle consists of multiple behaviors, which buffer the stress response (e.g., due to chronic health limitations or disabilities, an acute infection, or environmental challenges) and increase well-being.

Single ions of sleep, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake astudies support specific assumptions (see reference below). There is much evidence that different behaviors interrelate. Different studies support the assumption that carry-over mechanisms exist and showing that cognitive carry-over and behavioral outcomes depend on, for instance, whether physical activity resources are being transferred to nutrition behaviorpredictors of quality of life and subjective health across age groups: a theory based, cross-sectional web-based study. ResearchFrontiers in psychology, is9, still 977.

Taneeded, however, to extend assumptions of the CCAM. This is required by using different research designs, particularly longitudinal observations, Randomized Control Trials with experimentally testing effects, and complex analyses of different behaviors and how they change dependingS. L., Whittal, A., & Lippke, S. (2018). Associations among Sleep, Diet, Quality of Life, and Subjective Health. onHealth Behavior and Policy Review, each5(2), other46-58.

References

- Cihlar, V., & Lippke, S. (2017). Physical Activity Behavior and Competing Activities: Interrelations in 55-to 70-Year-Old Germans. Journal of aging and physical activity, 25(4), 576-586.

- Geller, K., Lippke, S., & Nigg, C. R. (2017). Future directions of multiple behavior change research. Journal of behavioral medicine, 40(1), 194-202.

- Liang, W., Duan, Y. P., Shang, B. R., Wang, Y. P., Hu, C., & Lippke, S. (2019). A web-based lifestyle intervention program for Chinese college students: study protocol and baseline characteristics of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC public health, 19(1), 1097.

- Lippke, S. (2014). Modelling and supporting complex behavior change related to obesity and diabetes prevention and management with the Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model. Journal of Diabetes & Obesity, 1(2), 1-5. https://www.ommegaonline.org/article-details/Modelling-and-Supporting-Complex-Behavior-Change-Related-to-Obesity-and-Diabetes-Prevention-and-Management-with-the-Compensatory-Carry-over-Action-Model/195

- Lippke, S. (2019). Compensatory Carry-Over Action Model. In Hackfort, D., Schinke, R. J., & Strauss, B. (Eds.). Dictionary of sport psychology: sport, exercise, and performing arts (pp. 53). London, UK: Academic Press/Elsevier.

- Lippke, S., & Cihlar, V. (2020). Social Participation during the Transition to Retirement: Findings on Work, Health and Physical Activity beyond Retirement from an Interview Study over the Course of 3 Years. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1-24.

- Lippke, S., & Schüz, B. (2019). Modelle gesundheitsbezogenen Handelns und Verhaltensänderung. In Gesundheitswissenschaften (pp. 299-310). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Storm, V., Reinwand, D., Wienert, J., Kuhlmann, T., De Vries, H., & Lippke, S. (2017). Brief report: Compensatory health beliefs are negatively associated with intentions for regular fruit and vegetable consumption when self-efficacy is low. Journal of health psychology, 22(8), 1094-1100.

- Tan, S. L., Storm, V., Reinwand, D. A., Wienert, J., de Vries, H., & Lippke, S. (2018). Understanding the positive associations of sleep, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake as predictors of quality of life and subjective health across age groups: a theory based, cross-sectional web-based study. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 977.

- Tan, S. L., Whittal, A., & Lippke, S. (2018). Associations among Sleep, Diet, Quality of Life, and Subjective Health. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 5(2), 46-58.