You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Maria Elena Aramendia-Muneta.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015 provides a catalogue of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). In this context, Circular fashion stands out as one of the sectors where commitment to the SDGs is most needed, given its global nature and its significant growth in terms of consumption. Moreover, it is not possible to assert that society, in general, is aware of the importance of the principles that guide circularity, both in terms of awareness and attitudes.

- circular fashion

- principles

- benefits

- enablers

- awareness

1. Principles of Circular Fashion–Awareness and Attitudes

The circular economy is defined by Kirchherr et al. [11][1] (p. 224), after analyzing 114 definitions, as “an economic system that is based on business models that replace the “end-of-life” concept with reduction, alternative reuse, recycling and recovery of materials in production, distribution and consumption processes, thus operating at a micro (products, companies, consumers), meso (eco-industrial parks) and macro (city, region, nation and beyond) levels, to achieve sustainable development, which implies creating environmental quality, economic prosperity and social equity, for the benefit of current and future generations”. This updated conceptualization suggests the transformation derived from linear economy into circular economy.

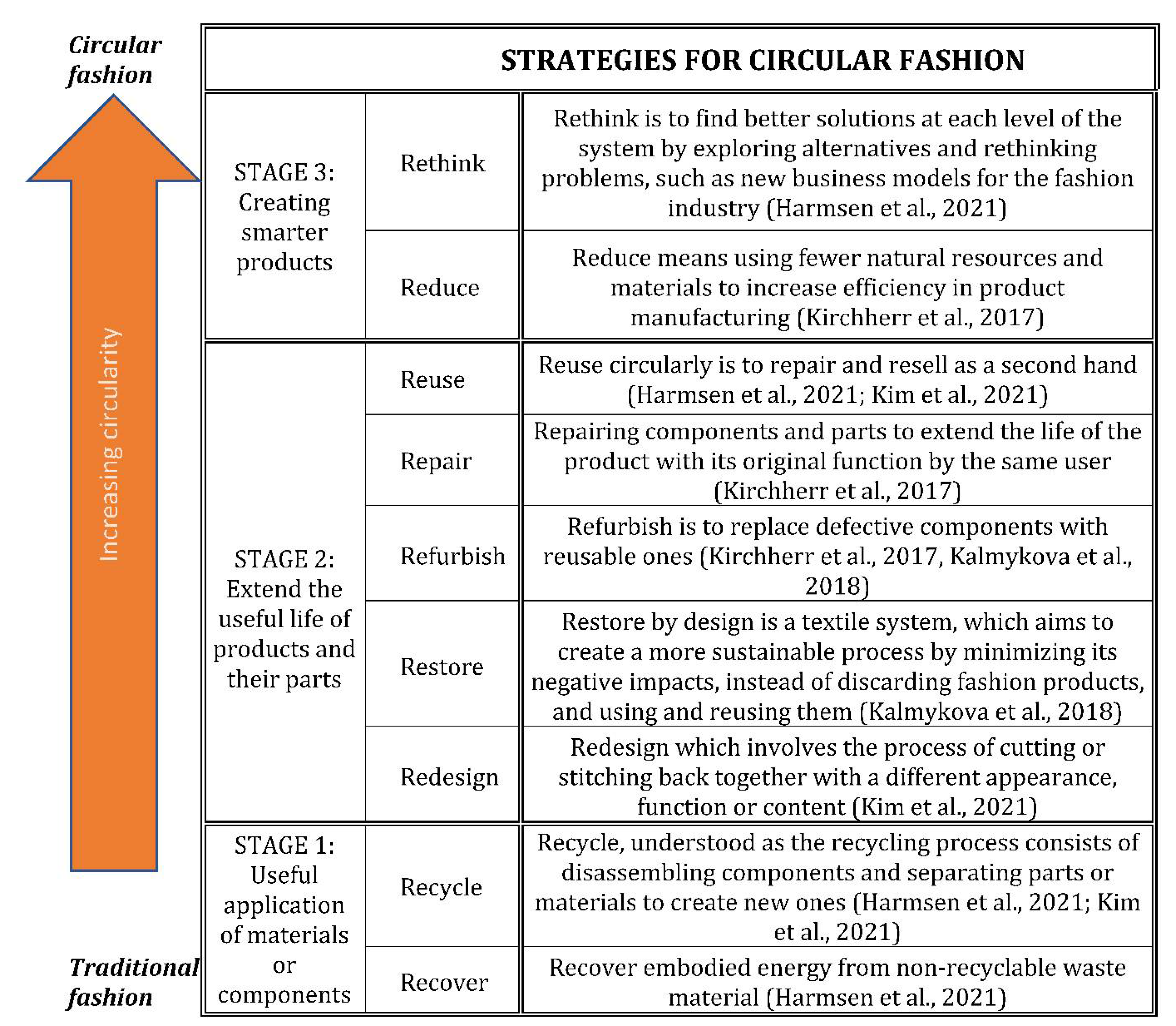

In this transition, Kirchherr et al. [11][1] proposed 9R framework strategies, adapted from Potting et al. [12][2]. In this study, this framework is adapted to circular fashion and further literature is updated [13,14,15][3][4][5] and therefore, the circular fashion 9R (Recover, Recycle, Redesign, Reduce, Refurbish, Repair, Restore, Rethink, Reuse) principles are proposed. Kirchherr et al. [11][1] proposed a classification of these principles and we adapt this transition from traditional to circular fashion. Figure 1 summarizes different stages in the evolution to circular fashion. Consumer behavior can help firms to identify different advertising strategies to introduce circular fashion as a key attribute to determine buying habits.

These transformative principles of circular fashion are not only part of the changing fashion industry, but consumers should also be able to know them and thus be able to apply them in order to improve social well-being. Awareness is the first step to advancing in circular fashion [16][6] and increasing the level of consumer awareness boosts the real meaning of sustainability [17][7]. Thus, consumer awareness is considered the major driver to guide circularity in the fashion industry [18][8].

Once the level of awareness is achieved, consumers have a better knowledge of the principles of circular fashion and hence they might be better motivated to act positively and change their behavior. In this line, Colucci and Vecchi [19][9] emphasized the need of researching consumers’ attitudes toward sustainable clothing as attitudes are led by awareness. These attitudes are drivers to influence purchase intention [20][10], which at a later stage is conducive to growing business profit.

2. Benefits of Circular Fashion to the Fashion Industry and Society

The most well-known benefit in the fashion industry affects the environment. Circular fashion seeks to decrease waste and expand the use of ecological and sustainable raw materials in the production and consumption cycle [21][11]. Reducing waste that causes damage to the environment (such as pesticides and dyes), leads to reduced global warming with lower greenhouse gas emissions [22][12].

Innovation is achieved by developing a pattern language for innovation management [23][13]. This innovation management creates high-quality products and efficient phases of the apparel design process. Circular fashion needs to increase the lifetime of resources by creating shared value for the whole society [24][14]. In addition, researchers have focused on proposing new models for the fashion industry; in this field, Bocken et al. [3][15] proposed a complete business model innovation based on primary (close-loop), secondary (downgrading or downcycling), tertiary (feedstock), and quaternary (energy recovery) recycling.

The fashion industry is still lagging in its acceptance of a truly circular fashion process, as they are not aware of the benefits to be gained. One of them is competitiveness. Competitiveness is increased in companies when a longer circulation is created by extending the product life cycle and reducing the cost [25,26][16][17]. The sustainable approach in companies by rethinking, reusing and upcycling waste leads to improved competitiveness, both for small and medium-sized companies [27][18].

Circularity in fashion incorporates the entire value chain in changing production [24,28][14][19]. This improvement becomes a competitive advantage and leads to better results, such as reduced energy consumption and the development of a cost structure less exposed to the risk of price volatility [27][18].

Another benefit is the impact on employment, creating new development and employment opportunities by fostering creativity, product and process innovation, and promoting the training of new skills [29,30][20][21]. This effect is beneficial for everybody, promoting the local economy by creating local employment and utilizing the local supply chain, which leads to new business opportunities [31][22].

3. Enablers of Circular Fashion for Consumption

The point of sale and the skills of salespeople are elements that influence consumer behavior and have an impact on increasing the purchase of sustainable fashion products [10][23]. The placement of sustainable products in the store satisfies consumers’ needs and promotes sustainable fashion consumption [32][24]. Companies focus to a large extent on creating the sustainable attributes of a specific product but do not go further in the second phase, which is selling the product in the right setting [4][25]. The acceptance of circular fashion products derives from the product itself, the sales process and communication (before, during, and after purchase).

Companies should enhance the communication skills of sales staff. Moreover, having sales staff inform the clientele about closed-loop operations would be a useful approach to spreading knowledge about circular fashion [4][25] and even act as mediators of corporate identity [33][26]. Indeed, fashion customers are more aware of the presence of in-store staff and their communication skills [34][27].

Marketing campaigns should include a clear message, consistent values, visually appealing and compelling products, and feedback loops [35][28]. Companies are supposed to provide sustainable reporting [36][29], thus benefiting from transparency and clear communication. Green communication aims to improve consumer awareness of environmental issues and environmentally friendly products [37][30].

Advertising strategies must be present for companies that want to engage potential customers in circular fashion. However, misleading advertising, such as the use of inaccurate eco-labels and logos or greenwashing leads the customer to distrust companies and the real benefits that circular fashion could bring to society and people’s well-being [38][31]. Nath et al. [39][32] highlight the power of green advertisements as a determining factor in shaping consumers’ environmental knowledge and influencing them to buy green products.

Consumer fashion behavior has changed significantly due to information and communication technologies and the widespread use of mobile devices, which have played an important role in the way people interact and use social media. Social media is a means to influence consumers to change their attitudes toward circular fashion [9,40][33][34]. They propose the use of Instagram micro-celebrities to better understand circular fashion and sustainability practices, such as online clothing rentals. Peer influence is decisive in pushing a group of followers into environmental behaviors [39][32].

4. Gender, Age, and Budget in Circular Fashion Attitudes and Awareness

The role of gender will eventually become important in circular fashion and will be relevant to understanding its impact on attitudes and awareness. Previous studies have shown that women are more informed about the concept of green [41][35]. In addition, Gazzola et al. [42][36] found that, in particular, young women and those with higher education or high-skilled occupations are more willing to participate in circular fashion.

Women tend to have a higher level of socialization and thus tend to be oriented towards social responsibility versus environmentalism [43][37]. The ecological attitude in purchasing reaches a deeper level among women compared to men [44][38]; above all, female personal values are more in line with sustainable consumption and caring for society. This psychological relationship is analyzed by Brough et al. [45][39], whose findings in their study reveal that males avoid ecological attitudes because they consider them to be feminine behavior.

Previous studies on environmental issues found that youngsters are more concerned than older people [46,47][40][41] and therefore age could be a determining factor in perceiving and behaving in a circular environment. When age and gender are combined at the same time, women, regardless of age, are more concerned about environmental issues and act more in favor of the environment [43][37].

Regarding age, some authors claim that young people are more aware and tend to buy more green fashion [43,48,49][37][42][43]. Lu et al. [48][42] found that Millennials are more willing to buy recyclable and reusable products. In contrast, Morgan and Birtwistle [50][44] revealed that young female consumers are not aware of the need to recycle clothing.

References

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232.

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain. 2017. Available online: https://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/downloads/pbl-2016-circular-economy-measuring-innovation-in-product-chains-2544.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Harmsen, P.; Scheffer, M.; Bos, H. Textiles for circular fashion: The logic behind recycling options. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9714.

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular economy—From review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201.

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ value and risk perceptions of circular fashion: Comparison between secondhand, upcycled, and recycled clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208.

- Galbreth, M.R.; Ghosh, B. Competition and sustainability: The impact of consumer awareness. Decis. Sci. 2013, 44, 127–159.

- Colasante, A.; D’Adamo, I. The circular economy and bioeconomy in the fashion sector: Emergence of a “sustainability bias”. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129774.

- Jia, F.; Yin, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, X. The circular economy in the textile and apparel industry: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120728.

- Colucci, M.; Vecchi, A. Close the loop: Evidence on the implementation of the circular economy from the Italian fashion industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2021, 30, 856–873.

- Mandarić, D.; Hunjet, A.; Vuković, D. The impact of fashion brand sustainability on consumer purchasing decisions. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 176.

- Jacometti, V. Circular economy and waste in the fashion industry. Laws 2019, 8, 27.

- Wijkman, A.; Skånberg, K. The Circular Economy and Benefits for Society. Jobs and Climate Clear Winners in an Economy Based on Renewable Energy and Resource Efficiency. 2016. Available online: https://www.clubofrome.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/The-Circular-Economy-and-Benefits-for-Society.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Le Pechoux, B.; Little, T.J.; Istook, C.L. Innovation management in creating new fashions. In Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 136–164.

- Ræbild, U.; Bang, A.L. Rethinking the fashion collection as a design strategic tool in a circular economy. Des. J. 2017, 20, S589–S599.

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320.

- Koszewska, M. Circular economy—Challenges for the textile and clothing industry. Autex Res. J. 2018, 4, 337–347.

- Ferioli, M.; Gazzola, P.; Grechi, D.; Vătămănescu, E.M. Sustainable behaviour of B Corps fashion companies during Covid-19: A quantitative economic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 134010.

- Cuc, S.; Tripa, S. Redesign and upcycling—A solution for the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises in the clothing industry. Ind. Text. 2018, 69, 31–36.

- Buchel, S.; Hebinck, A.; Lavanga, M.; Loorbach, D. Disrupting the status quo: A sustainability transitions analysis of the fashion system. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 231–246.

- Cuc, S.; Gîrneatə, A.; Iordənescu, M.; Irinel, M. Environmental and socioeconomic sustainability through textile recycling. Ind. Textila 2015, 66, 156–163.

- Cappellieri, A.; Borboni, E.; Tenuta, L.; Testa, S. Circular economy in fashion world. In Proceedings of the International Conference Sharing Society, Bilbao, Spain, 23–24 May 2019; Tejerina, B., Miranda de Almeida, C., Perugorría, I., Eds.; pp. 112–125.

- Leal Filho, W.; Ellams, D.; Han, S.; Tyler, D.; Boiten, V.J.; Paco, A.; Moora, H.; Balogun, A.L. A review of the socio-economic advantages of textile recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 10–20.

- Dissanayake, D.G.K.; Weerasinghe, D. Towards circular economy in fashion: Review of strategies, barriers and enablers. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 2, 25–45.

- Chan, T.-Y.; Wong, C.W.Y. The consumption side of sustainable fashion supply chain: Understanding fashion consumer eco-fashion consumption decision. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 193–215.

- Vehmas, K.; Raudaskoski, A.; Heikkilä, P.; Harlin, A.; Mensonen, A. Consumer attitudes and communication in circular fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2018, 22, 286–300.

- Hines, T.; Cheng, R.; Grime, I. Fashion retailer desired and perceived identity. In Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 230–258.

- Chu, A.W.C.; Lam, M.C. Store environment of fashion retailers: A Hong Kong perspective. In Fashion Marketing: Contemporary Issues; Hines, T., Bruce, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 151–167.

- Han, S.L.-C.; Henninger, C.E.; Blanco-Velo, J.; Apeagyei, P.; Tyler, D.J. The circular economy fashion communication canvas. In Proceedings of the Product Lifetimes and The Environment 2017—Conference Proceedings, Delft, The Netherlands, 30 November 2017; Bakker, C., Mugge, R., Eds.; pp. 161–165.

- Rutter, C.; Armstrong, K.; Blazquez Cano, M. The epiphanic sustainable fast fashion epoch. In Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Henninger, C.E., Alevizou, P.J., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 11–30.

- Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M.; Dibba, H. Factors influencing willingness to pay for sustainable apparel: A literature review. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 129–147.

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87.

- Nath, V.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, R.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, V. Consumer adoption of green products: Modeling the enablers. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 453–470.

- Shrivastava, A.; Jain, G.; Kamble, S.S.; Belhadi, A. Sustainability through online renting clothing: Circular fashion fueled by Instagram micro-celebrities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123772.

- Milanesi, M.; Kyrdoda, Y.; Runfola, A. How do you depict sustainability? An analysis of images posted on Instagram by sustainable fashion companies. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 101–115.

- Smith, K.T. An examination of marketing techniques that influence millennials’ perceptions of whether a product is environmentally friendly. J. Strateg. Mark. 2010, 18, 437–450.

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Pezzetti, R.; Grechi, D. Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: A gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2809.

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457.

- Costa Pinto, D.; Herter, M.M.; Rossi, P.; Borges, A. Going green for self or for others? Gender and identity salience effects on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 540–549.

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582.

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental segmentation alternatives: A look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 558–575.

- Zimmer, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green issues: Dimensions of environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 63–74.

- Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M. Green marketing: What the Millennials buy. J. Bus. Strategy 2013, 34, 3–10.

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545.

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198.

- Chang, H.J.; Watchravesringkan, K. (Tu) Who are sustainably minded apparel shoppers? An investigation to the influencing factors of sustainable apparel consumption. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 148–162.

More