Perovskia atriplicifolia (/pəˈrɒvskiə ætrɪplɪsɪˈfoʊliə/), commonly called Russian sage, is a flowering herbaceous perennial plant and subshrub. Although not a member of Salvia, the genus of other plants commonly called sage, it is closely related to them. It has an upright habit, typically reaching 0.5–1.2 m tall (1.6–3.9 ft), with square stems and grey-green leaves that yield a distinctive odor when crushed. It is best known for its flowers. Its flowering season extends from mid-summer to late October, with blue to violet blossoms arranged into showy, branched panicles. It is native to the steppes and hills of southwestern and central Asia. Successful over a wide range of climate and soil conditions, it has since become popular and widely planted. Several cultivars have been developed, differing primarily in leaf shape and overall height; 'Blue Spire' is the most common. This variation has been widely used in gardens and landscaping. P. atriplicifolia was the Perennial Plant Association's 1995 Plant of the Year, and the 'Blue Spire' cultivar received the Award of Garden Merit from the Royal Horticultural Society. The species has a long history of use in traditional medicine in its native range, where it is employed as a treatment for a variety of ailments. This has led to the investigation of its phytochemistry. Its flowers can be eaten in salads or crushed for dyemaking, and the plant has been considered for potential use in the phytoremediation of contaminated soil.

- atriplicifolia

- phytochemistry

- phytoremediation

1. Taxonomy and Phylogeny

Perovskia atriplicifolia was described by George Bentham in 1848, based on a specimen collected by William Griffith in Afghanistan,[1] now preserved at the Kew Gardens herbarium as the species's holotype.[2] The specific epithet atriplicifolia means "with leaves like Atriplex",[3] referring to its similarity to saltbush.[4] Commonly known as Russian sage, P. atriplicifolia is neither native to Russia nor a member of Salvia,[5] the genus generally referred to as sage.[6]

A Chinese population was described as a separate species in 1987 and given the name Perovskia pamirica,[7] but has since been considered synonymous with P. atriplicifolia.[8]

1.1. Phylogenetics

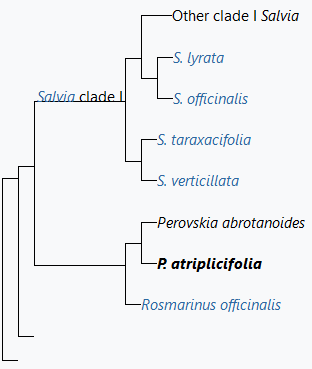

Within the family Lamiaceae, the large genus Salvia had long been believed monophyletic, based on the structure of its stamina. Several smaller genera, including Dorystaechas, Perovskia, and Meriandra were also included in tribe Mentheae, but were thought more distantly related. In 2004, a molecular phylogenetics study based on two cpDNA genes (rbcL and trnL-F) demonstrated that Salvia is not monophyletic, but comprises three identifiable clades. Clade I is more closely related to Perovskia than to other members of Salvia.[11]

P. atriplicifolia has been the subject of subsequent studies seeking to clarify the relationships within Mentheae. Further research combined palynological analysis of pollen grains with rbcL sequencing to provide additional support for the relationship between Perovskia and Salvia clade I. It also distinguished between P. atriplicifolia and P. abrotanoides, while confirming their close relationship.[12] A subsequent multigene study (four cpDNA markers and two nrDNA markers) redrew parts of the Mentheae cladogram, making Rosmarinus a sister group to Perovskia.[10]

1.2. Cultivars

Several cultivars of P. atriplicifolia have been developed. They are primarily distinguished by the height of mature plants and the depth of the leaf-margin incisions.[13] Many of these cultivars, especially those with deeply incised leaves, may actually be hybrids of P. atriplicifolia and P. abrotanoides.[13][14] In that context, some may be referred to by the hybrid name P. ×hybrida.[14][15]

The most common cultivar,[16] 'Blue Spire', is among those suspected of being a hybrid.[17][18] It was selected from German plantings by the British Notcutts Nurseries, and first exhibited in 1961.[19][20] 'Blue Spire' grows to approximately 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in), and has large, darker blue flowers.[5][17] In 1993, it received the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[21]

'Filigran' reaches a height of 1.2 to 1.3 m (3 ft 11 in to 4 ft 3 in); this tall, sturdy cultivar's name is German for filigree, in reference to its lacy, fern-like foliage.[5][19] 'Little Spire' is shorter, with a mature height of only 0.6 m (2 ft 0 in).[16][22] 'Longin' is similar in height to 'Blue Spire' but more upright.[5] Allan Armitage established the late-flowering cultivar 'Mystery of Knightshayes' from a plant at Knightshayes Court.[19] Other cultivars include 'Blue Haze', 'Blue Mist', 'Hybrida' (also called 'Superba'), 'Lace', 'Lisslit', 'Rocketman', and 'WALPPB'.[23][24][25][26]

2. Description

Perovskia atriplicifolia is a deciduous perennial subshrub with an erect to spreading habit.[13][27] Superficially, it resembles a much larger version of lavender.[28] Multiple branches arise from a shared rootstalk,[8] growing to a height of 0.5–1.2 m (1 ft 8 in–3 ft 11 in),[8][22] with occasional specimens reaching 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in).[4] The mature plant may be 0.6–1.2 m across (2 ft 0 in–3 ft 11 in).[4] The rigid stems are square in cross-section,[4] and are covered by an indumentum formed by stellate, or star-shaped, trichomes and oil droplets.[27] Especially during autumn, these hairs give the stems a silvery appearance.[29]

The grayish-green leaves are arranged in opposite pairs,[13][30] and attached to the stems by a short petiole.[27] They are generally 3–5 cm long (1.2–2.0-inch) and 0.8–2 cm wide (0.3–0.8-inch),[27] although narrower in some populations.[8] The overall leaf shape is oblate, a rounded shape longer than it is wide, to lanceolate, shaped like the head of a lance.[27] They are pinnatipartite,[8] with a deeply incised leaf margin that may be either wavy or sharp-toothed; even within a single community of P. atriplicifolia, there can be considerable variation in the details of leaf shape.[27] Leaves near the top of branches may merge into bracts.[27] The foliage is aromatic, especially when crushed,[4] with a fragrance described as sage-like,[5] a blend of sage and lavender,[16] or like turpentine.[31]

The flowering season of P. atriplicifolia can be as long as June through October,[27] although populations in some parts of its range, such as China, may bloom in a much more restricted period.[8] The inflorescence is a showy panicle, 30–38 cm long (12–15 in),[4] with many branches.[32] Each of these branches is a raceme, with the individual flowers arranged in pairs called verticillasters.[8] Each flower's calyx is purple, densely covered in white or purple hairs, and about 4 mm long (0.16-inch). The corolla is tube-shaped, formed from a four-lobed upper lip and a slightly shorter lower lip; the blue or violet blue petals are about 1 cm long.[8][32] The style has been reported in both an exserted—extending beyond the flower's tube—form and one contained within the flower;[32] all known examples of P. atriplicifolia in cultivation have exserted styles.[13] Gardening author Neil Soderstrom describes the appearance of the flowers from a distance as "like a fine haze or fog".[33]

Fruits develop about a month after flowering,[8] and consist of dark brown oval nutlets, about 2 mm × 1 mm (2⁄25 by 1⁄25 inch).[32]

Similar Species

Nine species of Perovskia are recognized.[34] P. abrotanoides shares much of the range of P. atriplicifolia, but is distinguished by its bipinnate leaves.[22][35] Hybrids between these two species may occur naturally.[27] Restricted to Turkestan in its native range, P. scrophularifolia is less upright; some forms have white flowers.[36] The flowers of P. scabiosifolia are yellow.[13]

3. Distribution, Habitat, and Ecology

Widely distributed across Asia in its native range, Perovskia atriplicifolia grows in western China,[4] Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran,[37] Turkey, and parts of eastern Europe.[38] It is found in steppes and on hillsides,[38] and grows at higher elevations in mountainous regions, including the Himalayas.[39] It has been recorded at 10,000 ft (3,000 m) of altitude in the Karakoram.[40] In Pakistan's Quetta district, it is often found in association with the grass Chrysopogon aucheri,[41] and may serve as an indicator species for soils with low calcium carbonate and chloride availability.[42] The harsh habitats preferred by P. atriplicifolia are comparable to the sagebrush steppe of North America.[43]

In parts of its range, such as the Harboi, these steppe ecosystems are employed as rangeland for grazing animals such as sheep and goats, although this forage is generally of poor nutritional quality. P. atriplicifolia can serve as an important source of phosphorus and zinc,[44] despite being high in poorly-digested material such as neutral detergent fiber and lignin.[45]

4. Cultivation

Following its introduction to the United Kingdom in 1904, the Irish gardener and author William Robinson was immediately taken with the plant, which he described as being "worth a place in the choicest garden for its graceful habit and long season of beauty."[20] The Royal Horticultural Society records the establishment of cultivars beginning with P. 'Hybrida', selected at a Hampshire nursery in the 1930s.[19] By the late 1980s and early 1990s, P. atriplicifolia had gained widespread popularity,[46] and in 1995, it was selected as the Perennial Plant Association's Plant of the Year.[47]

The cultivar ‘Blue Spire ‘ has gained the Royal Horticultural Society’s Award of Garden Merit.[48][49]

4.1. Planting and Care

P. atriplicifolia is a perennial plant suitable for a wide range of conditions. The species prefers full sun.[47] Specimens planted in partially shaded locations tend to spread or flop,[4] although this behavior can be controlled somewhat by pinching young shoots or by providing a strong-standing accompaniment that the plant can drape itself around for support.[50][51] Flowers bloom only on new growth.[52] Plants trimmed to 15–61 cm (5.9–24.0 in) in early spring provide the best subsequent growth and flowering.[13][53]

Tolerant of both heat and cold, it is grown in North America in United States Department of Agriculture hardiness zones three through nine,[4][47] although some cultivars may be better suited than others to extremes of temperature.[46][54] It is successfully grown from the southwestern United States, north and east across much of the country,[55] and across the Canada–US border into Ontario and Quebec.[19][56] In the coldest of these areas, it may require considerable protection to survive the winter.[57] In the United Kingdom, the Royal Horticultural Society has assigned it hardiness rating H4,[54] indicating that it tolerates temperatures as low as −10 to −5 °C (14 to 23 °F), hardy in most of the country through typical winters.[58]

It also tolerates a variety of soil conditions. Although young specimens perform best when planted in a mixture of peat and either sand or perlite,[59][60] P. atriplicifolia can thrive in sandy, chalky, or loamy soil,[18] or heavy clay soil with sufficient drainage.[61] It can endure a wide range of soil pH,[18] as well as exposure to salty conditions near oceans.[16] Its deep-feeding taproot makes it especially drought tolerant;[62] for this reason it has seen wide use for xeriscaping in the Intermountain West.[63] Overwatering and over-fertilization can damage its roots and lead to a rapid decline in health.[61][64] P. atriplicifolia is otherwise generally free from plant pathogens.[16] In cultivation, it is also rarely selected as forage by grazing animals, and so is considered both a deer-resistant and rabbit-resistant plant.[5][65]

4.2. Landscaping

Popular landscaping authors, including Gertrude Jekyll and Russell Page, have praised P. atriplicifolia for its usefulness in gardens and landscaping features.[66] It is most commonly planted as an accent feature,[47] such as an "island" in an expanse of lawn,[67] but it can also be used as filler within a larger landscaping feature,[53] or to enhance areas where the existing natural appearance is retained.[67] Gardening author Troy Marden describes P. atriplicifolia as having a "see-through" quality that is ideal for borders.[68] Some experts suggest groups of three plants provide the best landscape appearance.[46] It is also suitable for container gardening.[69]

It attracts bees,[70] birds,[69] and butterflies,[5] and contributes color to gardens—both the blue of its late-season flowers,[20] and the silvery colors of its winter stalks.[71]

4.3. Propagation

P. atriplicifolia is frequently propagated by cuttings. Because its woody crown is resistant to division, softwood cuttings are taken from shoots near the base, generally in late spring.[13][57] Hardwood cuttings selected in mid-to-late summer also provide a viable propagation technique.[13][16] The plant is also grown from seed in cultivation. Such seeds require exposure to cold for 30–160 days to germinate,[47][72] and seed-raised specimens may not preserve the characteristics of named cultivars.[54] In the commercial greenhouse or nursery setting, P. atriplicifolia's relatively large size and rapid growth can adversely affect quality or make plants more difficult and expensive to transport; the use of plant growth regulators such as chlormequat chloride and daminozide may be more cost-effective than large-scale pruning.[73]

Some members of the Lamiaceae can spread unchecked and become invasive plants.[74] Planting of P. atriplicifolia near wild lands has been discouraged by some gardening guides out of concern for its potential to spread,[75][76] but it is not considered invasive,[65] and has been suggested as a substitute for purple loosestrife for this reason.[77]

5. Uses

Perovskia atriplicifolia has a long history of use in traditional medicine, especially as an antipyretic.[78][79] It has also been employed as an antiparasitic and analgesic in Tibet,[80] and smoked elsewhere as a euphoriant.[81] In Balochistan, Pakistan, a decoction of the plant's leaves and flowers has been considered an anti-diabetic medication and a treatment for dysentery.[82]

In addition to its use in folk medicine, P. atriplicifolia is sometimes used in Russia to flavor a vodka-based cocktail.[83] Its flowers are eaten in parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan, including Kashmir,[84] adding a sweet flavor to salads;[79] they can also be crushed to yield a blue colorant that can be employed in cosmetics or as a textile dye.[85] This species is considered a candidate for use in phytoremediation because of its rapid growth, tolerance for harsh conditions, and ability to accumulate toxic heavy metals from polluted soil.[86]

Phytochemistry

Because of its extensive ethnomedical tradition,[78] the phytochemistry of P. atriplicifolia has been the topic of several studies. Analysis of the plant's essential oil has identified over two dozen compounds,[87] although the compounds detected and their relative prevalence have not been consistent. Most analyses have identified various monoterpenes and monoterpenoids as the dominant components, such as carene, eucalyptol, limonene, γ-terpinene, and (+)-β-thujone,[87][88] although the essential oil of a sample from the Orto Botanico dell'Università di Torino had camphor as its most prevalent component.[89] Other monoterpenes, camphene, α-pinene,[90] and β-pinene are also present,[87] as are sesquiterpenes such as γ-cadinene,[90] δ-cadinene, trans-caryophyllene, and α-humulene.[88] Several terpenoid alcohols—borneol, cedrol, and menthol[87]—have been extracted from P. atriplicifolia, as have caffeic acid and ferulic acid.[91] More complex compounds have been isolated, some of which were first identified in this manner, including perovskatone;[80] the glycosides atriplisides A and B;[92] and atricins A and B, a pair of triterpenes that are similar to oleanane.[78]

The essential oil has displayed antimicrobial properties in vitro,[79] and can function as a biopesticide, especially regarding Tropidion castaneum beetles and Camponotus maculatus carpenter ants.[93] Several terpenoids isolated from P. atriplicifolia have been investigated for potential inhibitory effects on the hepatitis B virus.[94][95] Its traditional use as an anti-inflammatory has been attributed to the ability of the lignan (+)-taxiresinol and five other compounds to act as leukotriene antagonists.[96] The isorinic acid derivative perovskoate may also contribute to an anti-inflammatory effect as an arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor.[91] Interaction with opioid and cannabinoid receptors has been proposed as the mechanism of traditionally reported analgesic effects.[97]

References

- Bentham 1848, p. 261.

- Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

- Harrison 2012, p. 224.

- Missouri Botanical Garden (a).

- Hightower.

- Kintzios 2000, pp. xi–xv.

- Yang & Wang 1987, pp. 95–101.

- Wu & Raven 1994, p. 224.

- Moon et al. 2008, p. 465.

- Drew & Sytsma 2012, pp. 938, 941.

- Walker et al. 2004, pp. 1115, 1119–1120, 1112.

- Moon et al. 2008, p. 465–466.

- Grant 2007, p. 2.

- Hodgson 2000, p. 441.

- Royal Horticultural Society (b).

- Yemm 2003.

- Cox 2002, p. 242.

- Royal Horticultural Society (a).

- Grant 2007, p. 5.

- Bourne 2007.

- "RHS Plantfinder - Perovskia ‘Blue Spire’". https://www.rhs.org.uk/Plants/93157/i-Perovskia-i-Blue-Spire/Details. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Grant 2007, p. 4.

- Grant 2007, pp. 4–5.

- Missouri Botanical Garden (b).

- Missouri Botanical Garden (c).

- Missouri Botanical Garden (d).

- Hedge 1990, p. 221.

- Keys & Michaels 2015, p. 195.

- Gardiner 2014, p. 267.

- Sanecki 1975, p. 240.

- Lacey 1995, p. 58.

- Hedge 1990, pp. 218–221.

- Soderstrom 2009, p. 309.

- Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden.

- Eisenman, Zaurov & Struwe 2012, p. 188.

- Grant 2007, pp. 2, 5.

- Proctor 1999, p. 107.

- Burrell 2002, p. 53.

- Mani 1978, p. 113.

- nullCurtis's Botanical Magazine 1912.

- Tareen & Qadir 1991, p. 99.

- Tareen & Qadir 1991, p. 113.

- Kingsbury 2014, p. 145.

- Hussain & Durrani 2008, pp. 2513–2514, 2517, 2520.

- Hussain & Durrani 2009, pp. 1149–1151.

- Roth & Courtier 2015, p. 189.

- Perennial Plant Association.

- "RHS Plantfinder - Perovskia ‘Blue Spire’". https://www.rhs.org.uk/Plants/93157/i-Perovskia-i-Blue-Spire/Details. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental". Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 75. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/pdfs/agm-lists/agm-ornamentals.pdf. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- DiSabato-Aust 2006, pp. 89, 124.

- Schneller 2012, p. 132.

- Lowe 2012, p. 171.

- Breen, Zanden & Hilgert 2004.

- Grant 2007, p. 3.

- Singer 2006, p. 162.

- Vinson & Zheng 2012.

- Tenenbaum 2003, p. 295.

- Rice 2013.

- Squire 2007, p. 71.

- Dumitraşcu 2008, pp. 215–218.

- Bost & Polomski 2012, p. 63.

- Weiseman, Halsey & Ruddock 2014, p. 250.

- Calhoun 2012, p. 98.

- Diblik 2014, p. 110.

- Munts & Mulvihill 2014, p. 165.

- Gardner 1998, p. 236.

- Henehan 2008, pp. 84, 98.

- Marden 2014, p. 158.

- Better Homes and Gardens.

- Winter 2009, p. 12.

- Kahtz 2008, p. 162.

- Rose, Selinger & Whitman 2011, p. 187.

- Burnett et al. 2001, pp. 24–28.

- Brickell & Cole 2002, p. 605.

- Cretti & Newcomer 2012, p. 118.

- Greet 2013, p. 25.

- Shonle 2010.

- Perveen, Malik & Tareen 2009, p. 266.

- Erdemgil et al. 2007, pp. 324–331.

- Jiang et al. 2013, p. 3886.

- Zamfirache et al. 2011, p. 261.

- Tareen et al. 2010, p. 1476.

- Severa 1999, p. 118.

- Roy, Halder & Pal 1998, p. 118.

- Pippen 2015, p. 112.

- Zamfirache et al. 2011, p. 267.

- Zamfirache et al. 2010, p. 45.

- Erdemgil et al. 2007, pp. 324–325.

- Erdemgil et al. 2007, pp. 324.

- Jassbi, Ahmad & Tareen 1999, pp. 38–40.

- Perveen et al. 2006, pp. 347–353.

- Perveen et al. 2014, pp. 863–867.

- Sahayaraj 2014, p. 132.

- Jiang, Yu, et al. 2015, pp. 241–246.

- Jiang, Zhou, et al. 2015, pp. 3844–3849.

- Ahmad et al. 2015, pp. 1628–1631.

- Tarawneh et al. 2015, pp. 1461–1465.

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia