The RIAL-CYTED harbors a multidisciplinary Ibero-American network of clinical and basic researchers created to form a platform of multi-center cooperation focusing on increasing our knowledge of lymphoma, particularly for more underdeveloped or developing regions. This network aims to improve the diagnosis and prognosis of these neoplasms throughout LA by way of homogenizing its identification and classification. With that purpose, in this review, we sought to systematically organize and analyze the literature related to the lymphotropic and lymphomagenic viruses EBV, KSHV and HTLV-1, in order to better understand their loco-regional distribution and the risk our population carries in terms of developing lymphoma.

- Epstein–Barr virus

- Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus

- human T-lymphotropic virus

- lymphoma

- Latin America

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) and human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) are lymphomagenic viruses with region-specific induced morbidity. The RIAL-CYTED aims to increase the knowledge of lymphoma in Latin America (LA), and, as such, we systematically analyzed the literature to better understand our risk for virus-induced lymphoma. We observed that high endemicity regions for certain lymphomas, e.g., Mexico and Peru, have a high incidence of EBV-positive lymphomas of T/NK cell origin. Peru also carries the highest frequency of EBV-positive classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and EBV-positive diffuse large B cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (NOS), than any other LA country. Adult T cell lymphoma is endemic to the North of Brazil and Chile. While only few cases of KSHV-positive lymphomas were found, in spite of the close correlation of Kaposi sarcoma and the prevalence of pathogenic types of KSHV. Both EBV-associated HL and Burkitt lymphoma mainly affect young children, unlike in developed countries, in which adolescents and young adults are the most affected, correlating with an early EBV seroconversion for LA population despite of lack of infectious mononucleosis symptoms. High endemicity of KSHV and HTLV infection was observed among Amerindian populations, with differences between Amazonian and Andean populations.

1. Introduction

Neoplasms of an infectious etiology account for about 16% of all cancers, which amounts to about two million cases per year, considering virus-, bacteria- and parasite-derived cancers. Interestingly, this number is significantly higher for developing countries, in which it can be as high as 30%, while in highly industrialized countries, such as the US, it can be as low as 5% [1]. The bases for this difference are not clear, but it may be due to the prevalence of the oncogenic infectious agents, or to additional co-factors causally linked to the infectious neoplasms.

Virus-derived cancers almost always originate from established chronic viral infections, because the mechanisms of viral persistence in the infected host are compatible with oncogenesis. Indeed, all human oncogenic viruses express proteins, and/or non-coding RNAs with the capacity to transform cells in culture and induce cancer in transgenic animals [2]. Viral oncogenes tend to enhance cell proliferation and survival, aiming to maintain the pool of infected cells during persistent infections. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) acknowledges seven viruses as direct human oncogenic agents: the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV), human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), high risk human papillomaviruses (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) [3]. Although the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is also causally associated with several neoplasms, it is as an indirect oncogenic agent, due to the immunosuppression it imposes upon the infected host.

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was the first oncogenic virus discovered 56 years ago by Dr. Anthony Epstein and Dr. Ivonne Barr. EBV was initially observed in samples of Burkitt lymphoma (BL) coming from the equatorial Africa, which represents the perfect example of the unequal geographical distribution of neoplasms of infectious origin. While EBV is responsible for close to 100% of the BL originating in this region, EBV only accounts for about 20% of all BLs in developed countries (see below). We later understood that whilst EBV is evenly distributed around the world, the African BL is also associated with repetitive infections with Plasmodium falciparum, an important co-factor of this neoplasm and a parasite endemic to this area. Today, BL is classified within three distinct clinical types, endemic (malaria- and EBV-associated), sporadic (derived from areas in which malaria is not holoendemic) and immunodeficiency-associated [4].

The world distribution of the oncogenic viruses varies significantly, while most adults are already infected with EBV, HPV and MCPyV indistinct of the geographic region, the others tend to be more prevalent in specific populations [2]. Even today, despite the global means of transportation and increased immigration that have allowed a more heterogeneous mix of populations, the prevalence of KSHV and HTLV-1 infection is still restricted to particular geographical areas, implying mechanisms of viral persistence in the population that are not explained by mere socioeconomic factors, but in which genetic susceptibilities, ethnic origin, culture and the prevalence of co-factors may be critical (see below). Like EBV, KSHV and HTLV-1 are associated with lymphoid neoplasms [2]. While EBV mainly infects and persists in B cells, KSHV and HTLV-1 persist in B cells and T cells, respectively, and, as such, they have been associated with B and T cell lymphomas [2].

Latin America (LA) comprises the land from Mexico to Argentina and the Spanish speaking Caribbean, countries with a complex mix of geographies, climates, politics, cultures, ethnicities and different levels of socioeconomic development, and, in which, a high prevalence of oncogenic viruses, acute tropical diseases and malnourishment collide. Early epidemiological studies documented a high seroprevalence of KSHV and HTLV-1 in some regions of LA, and to this day, it is common to find in the scientific literature that these viruses are endemic to LA (see below). However, the loco-regional estimation of their prevalence and induced morbidity remains poorly known. The RIAL-CYTED harbors a multidisciplinary Ibero-American network of clinical and basic researchers created to form a platform of multi-center cooperation focusing on increasing our knowledge of lymphoma, particularly for more underdeveloped or developing regions. This network aims to improve the diagnosis and prognosis of these neoplasms throughout LA by way of homogenizing its identification and classification.

2. Epstein–Barr Virus

EBV is a human gamma-1 herpesvirus usually persisting as a harmless passenger; its growth-transforming ability is linked to a range of lymphoproliferative lesions and malignant lymphomas [5]. EBV-associated lymphomas vary according to the geographic location, age, sex, genetic background and socioeconomic condition [6]. Additionally, the age of primary infection varies substantially worldwide, correlating with socioeconomic factors [7]. In underdeveloped and developing populations, EBV infection is acquired at a young age and is usually asymptomatic. A delay in acquiring primary infection until adolescence or young adulthood, which usually occurs in more developed countries, can manifest as infectious mononucleosis (IM) in 25–75% of the late infected persons [8].

EBV infection has been associated with the following lymphomas in addition to BL: Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), lymphomas in immunosuppressed individuals (post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) and HIV-associated lymphoproliferative disorders and T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas) [3]. Furthermore, the last WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues included two new entities specifically associated with EBV: EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified (NOS) and systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma of childhood [9]. Since the incidence of HIV- and transplant-related lymphoma is more informative of the HIV prevalence or the number of transplanted patients than of the EBV distribution, we will not cover them in this review. See Table 1 for the studies considered and the frequency of EBV association.

Table 1. Summary of studies about Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) associated lymphomas.

|

Country (Ref) |

Lymphoma Type |

Type of Study |

Methods |

EBV Association |

Description of the Study |

|

|

DLBCL (ad/ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

12.6% (12/95) |

26 DLBCL ped; 69 DLBCL ad from Buenos Aires, Argentina. EBV prevalence 72% ped. |

||

|

Argentina [13] |

PBL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 PBL in HIV+ patient from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [14] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

29% IHC (7/24); 100% ISH (3/3) |

27 pediatric BL, 3 HIV+ from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [15] |

PBL |

4 cases |

ISH, IHC |

100% (4/4) |

4 PBL in HIV+ patients from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [16] |

B-NHL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

40% (16/40) (35% BL; 47% DLBCL) |

23 BL ped, 17 DLBCL ped from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [17] |

PBL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 PBL in HIV+ from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [18] |

PBL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 PBL in HIV+ from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [19] |

T-NHL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

8% (2/25) |

16 lymphoblastic, 8 anaplastic, 1 hepatoesplenic T-cell lymphoma ped from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina/Brazil [20] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

54% (Arg; 60/111); 48% (Bra; 31/65) |

111 HL ped from Buenos Aires, Argentina. 65 HL ped from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

|

|

Argentina [21] |

PCNSL |

7 cases |

ISH, PCR |

100% (6/6) |

7 PCNSL cases HIV+ from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [22] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

55% ped (51/92); 31% ad (25/81) |

92 HL ped, 81 HL ad from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [23] |

HIV+ HL, BL, DLBCL |

4 cases |

ISH, IHC |

100% (4/4) |

1 HL, 2 BL, 1 DLBCL ped HIV+ from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

Argentina [24] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, PCR |

47% (8/17) |

17 BL ped from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

|

|

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

51% (22/41) |

41 HL ped from Buenos Aires, Argentina. |

||

|

Argentina [28] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

25% (4/16) |

16 BL ped from La Plata, Argentina. |

|

|

Brazil [29] |

DLBCL |

Cohort |

ISH |

30% (28/93) |

93 DLBCL ad from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [30] |

NT/NKL |

Case report |

IHC |

100% |

1 NK/NKL from Rio Janeiro, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [31] |

HVL-LD |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 HVL- LD from Dom Eliseu City, Pará, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [32] |

HL (ad/ped, temporal series) |

Cohort |

ISH |

87–46% (817) |

155 HL ped, 662 HL ad from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [33] |

Intermediate BL with DLBCL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 int BL DLBCL from Recife, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [34] |

DLBCL (> 50 yo) |

Cohort |

ISH |

8.45% (6/71) |

71 DLBCL ad from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [35] |

T/NKL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

T/NKL HIV+ from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [36] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

100% (7/7) |

4 BL ped, 3 BL ad from Amazonas, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [37] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

54.1% (33/61) |

61 BL ped from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [38] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

43% (56/130) |

130 HL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [39] |

HVL-LD |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 HVL-LD from Manaus Amazonas, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [40] |

DLBCL, Palatine tonsil |

Cohort |

ISH |

0% (0/26) |

26 DLBCL from Bahia, Brazil. |

|

|

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

44.8% (43/96) |

96 HL ped from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

||

|

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH |

52.6% (51/97) |

97 HL ad from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

||

|

Brazil [46] |

ENKTCL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, PCR |

100% (74/74) |

74 ENKTCL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [47] |

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH |

22% (5/23) |

23 HL ad from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [48] |

CNS DLBCL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH |

5.5% total (2/36) (40% IS) |

36 CNS DLBCL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [49] |

HL (stomach) |

5 cases |

ISH |

80% (4/5) |

5 HL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [50] |

B-NHL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, qPCR |

23% (7/30) |

30 NHL ped from Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [51] |

HL + PTL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

HL PTL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [52] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

50.3% (85/169) |

169 HL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

BL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

52.6 % (123/234) |

North Region(n = 17 cases), Central West Region(n = 17 cases), Northeast Region(n = 86 cases), Southeast Region(n = 72 cases), South Region(n = 42 cases) |

||

|

Brazil [55] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

66% (33/50) |

143 pediatricos y 88 adultos, 3 sin edad). |

|

|

Brazil [56] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

61% (33/54) |

San pablo |

|

|

Brazil [57] |

PBL |

11 cases |

ISH, PCR |

100% (11/11) |

Rio de janeiro |

|

|

Brazil [58] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

48% (22/46) |

San pablo |

|

|

Brazil [59] |

PCNSL |

10 cases |

IHC |

10% (1/10) |

Florianopolis, South of Brazil |

|

|

Brazil [60] |

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

IHC, PCR |

37% (11/30); 43% Circulating EBV |

14 patients < 15 years y 32 > 15 years |

|

|

Brazil [61] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

86.7% (78/90) |

Niterói RJ |

|

|

B-NHL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, PCR |

72% (21/29) |

29 NHL from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

||

|

Brazil [65] |

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

75.6% (28/37) |

37 HL ad from Ceara, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [66] |

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

IHC |

45.8% (38/83) |

83 HL ad from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [67] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

IHC |

55% (35/64) |

64 HL ad from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

|

|

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

64.1% (50/78) |

78 HL ad from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

||

|

Brazil [70] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

63.5% (61/96) |

96 HL from Sao Paulo and Ceara, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [71] |

ENKTCL |

Cohort |

ISH |

100% (16/16) |

16 ENKTCL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [72] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

73% (8/11) |

11 BL ped from Recife, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [73] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

57.7% (15/26) |

26 HL ped from Curitiba, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [74] |

BL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

87% (47/54) |

54 BL ped from Bahia, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [75] |

BL |

Cohort |

ISH |

71% (17/24) |

24 BL from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Brazil [76] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

72% (18/25) |

25 HL ped from Sao Paulo, Brazil. |

|

|

Mexico [77] |

HVL-LD |

Cohort |

ISH |

100% (20/20) |

20 HVL-LD ped from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [78] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

76.1% ped (22/42); 66.6% ad (16/24) |

42 HL ped, 24 HL ad from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [79] |

PCL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

1 PCL from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [80] |

PBL |

5 cases |

PCR |

80% (4/5) |

5 PBL ad HIV+ from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [81] |

DLBCL ( > 50 yrs) |

Cohort |

ISH |

7% (9/136) |

136 DLBCL ad from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [82] |

HL (mostly ad) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

61.4% (35/57) |

54 HL ad, 3 HL ped from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [83] |

ENKTCL |

Cohort |

ISH |

96% (22/23) |

23 ENKTCL from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico/Bolivia [84] |

HVL-LD /ACTCLC |

4 cases |

ISH |

75% (3/4) |

4 ACTCLC ped from Mexico City and La Paz |

|

|

Mexico [85] |

PTLD |

8 cases |

ISH |

100% (8/8) |

8 PTLD ad from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

Mexico [86] |

NHL, Intestinal |

Cohort |

ISH |

63% (12/19) |

7 T, 6 high grade B, 6 low grade B-NHLs from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

HL (ad) |

Cohort |

IHC |

70% (35/50) |

50 HL ad from Mexico City, Mexico. |

||

|

Mexico [89] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

67% (18/27) |

3 HL ped, 24 HL ad from Mexico City, Mexico. |

|

|

PR [90] |

HL & NHL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

IHC |

50% HL (11/22); 35% NHL (22/63) |

22 HL, 63 NHL from San Juan de Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico. |

|

|

DR [91] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

IHC |

64.3% (18/28) |

28 HL ped from Santiago, Dominican Republic |

|

|

Cuba [92] |

BL (ped) |

7 cases |

EBV Serology |

85.7% (6/7) |

EBV prevalence in 7 BL ped from La Habana, Cuba. |

|

|

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

67% (45/67) 60.4% ad; 84.2% ped |

48 HL ad, 19 HL ped from Bogotá, Colombia |

||

|

Peru [95] |

DLBCL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH |

28% (33/117) |

117 DLBCL ad from Lima and Arequipa, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [96] |

LBCL in cardiac myxoma (ad) |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

LBCL ad from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [97] |

HVL-LD |

4 cases |

ISH |

100% (3/3) |

4 HVL-LD ped from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [98] |

EBV+ DLBCL GI (ad) |

5 cases |

ISH |

100% (5/5) |

5 DLBCL GI ad from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [99] |

Systemic T/NKL |

6 cases |

ISH, IHC |

100% (6/6) |

6 T/NKL ped from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

EBV+ DLBCL ( > 50 yo) |

Cohort |

ISH |

14% (28/199) |

199 DLBCL ad from Lima, Peru. |

||

|

Peru [102] |

DLCBL in a HTLV-1+ |

Case report |

ISH |

100% |

DLBCL ad from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [103] |

Cutaneous T/NKL (11/15 HVL-LD) |

Cohort |

ISH |

100% (15/15) |

12 T/NKL ped, 2 T/NKL ad from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [104] |

ENKTCL |

Cohort |

PCR |

99% (76/77) |

77 ENKTCL from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [105] |

HVL-LD |

6 cases |

ISH |

100% (6/6) |

6 HVL-LD ped from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [106] |

ENKTCL |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

96% (27/28) |

28 ENKTCL ad from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [107] |

Nasal lymphoma |

Cohort |

ISH |

93% (14/13; 11/11 T-cell) |

13 Nasal lymphoma from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Peru [108] |

HL (mostly ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

94% (30/32) |

32 HL from Lima, Peru. |

|

|

Ecuador [109] |

HVL-LD |

2 cases |

ISH |

100% |

1 HVL-LD ped, 1 HVL-LD ad from Quito, Ecuador. |

|

|

Ecuador [110] |

HL and NHL (ad) |

Cohort |

ISH, qPCR |

55.5% HL (5/9); 59.5% NHL (25/42) |

9 HL ad, 42 NHL ad from Guayaquil, Ecuador. |

|

|

Chile [111] |

EBV+ DLBCL |

Case report |

ISH |

100% (Leukocytoclastic vasculitis) |

DLBCL from Santiago, Chile. |

|

|

Chile [112] |

Nasal lymphoma |

Cohort |

ISH |

DLCBL 0% (0/3); T-cell 0% (0/1); NKT 100% (6/6) |

3 DLBCL, 1 T-cell lymphoma, 6 NKT from Valdivia, Chile. |

|

|

Chile [113] |

ENKTCL |

Cohort |

ISH |

78% (7/9) |

9 ENKTCL ad from Santiago, Chile. |

|

|

Chile /Argentina /Brazil [114] |

BL (mostly ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

41% (7/17 Arg); 50% (5/10 Chile); 58% (7/12 Br) |

37 BL ped, 2 BL ad from Buenos Aires, Argentina; Santiago, Chile; Campinas, Brazil. |

|

|

Honduras [115] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH |

100% (11/11) |

11 HL ped from Tegucigalpa, Honduras. |

|

|

CR [116] |

HL (ad, ped) |

Cohort |

IHC |

40% (16/40) |

6 HL ped, 34 HL ad from San Jose, Costa Rica. |

|

|

CR [117] |

HL (ped) |

Cohort |

ISH, IHC |

81% (34/42) |

42 HL from San José, Costa Rica. |

|

|

CR/Mexico [118] |

HL (ad, > 15 yo) |

Cohort |

ISH, SB |

36% (5/14) CR; 77% (24/31) Mexico |

45 HL ad from Mexico City, Mexico; San Jose, Costa Rica. |

|

|

Bolivia [119] |

NHL |

8 cases |

ISH |

75% (6/8) |

8 NHL from Santa Cruz, Bolivia. |

|

|

Guatemala [120] |

ENKTCL |

Cohort |

ISH |

87% (73/84) |

59 ENKTCL from Guatemala City, Guatemala. |

|

ACTCLC: angiocentric cutaneous T-cell lymphomas of childhood; B-NHL: B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CNS: central nervous system; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; DLBCL: diffuse large B cell lymphoma; GI, gastrointestinal; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; HVL-LD: hydroa vacciniform-like lymphoproliferative disease; IC: immunocompetent; IHC: immunohistochemistry; IS: immunosuppressed; ISH: Epstein–Barr virus-encoded small RNAs (EBERs) in situ hybridization; ENKTCL: extranodal nasal-type T-cell/NK lymphoma, PBL: plasmablastic lymphoma; PCL: plasma cell myeloma; PCNSL: primary central nervous system lymphoma; PTL: peripheral T cell lymphoma; qPCR: quantitative real-time PCR; SB: Southern blot; T-NHL: T-cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; Pt: patient; ad: adult; ped: pediatric. Countries PR, DR and CR: Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic and Costa Rica. virus+ refers to virus positive samples.

2.1. EBV-Associated Lymphoid Neoplasms in Latin America

2.1.1. Hodgkin Lymphoma

There are several series of lymphomas reported in this region, particularly at the end of last century, which, however, were only classified as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin (NHL), and which obviously did not follow the latest WHO classification. HL has a bimodal age distribution, there is an early peak occurring in adolescents and young adults, and a late peak after 50 years of age in industrialized countries. Developing countries also exhibit a bimodal distribution of the disease, but the early peak starts before adolescence [121]. In the US, pediatric HL shows the highest incidence in adolescents between 15–19 years of age, while developing countries present similar incidences than the US for adolescents, but also exhibit a marked augmented incidence in young children [122][123][122,123]. In developing countries, classical HL (cHL) with an early onset (14 yrs or younger) shows high EBV association, more often of the mixed cellularity (HL-MC) subtype. A strong male to female predominance is also observed, particularly in the group younger than 5 yrs, in which the ratio is 5:1. HL in adolescents and young adults displays lower EBV association, nodular sclerosis subtype (HL-NS) predominance and affects male and females almost equally [122].

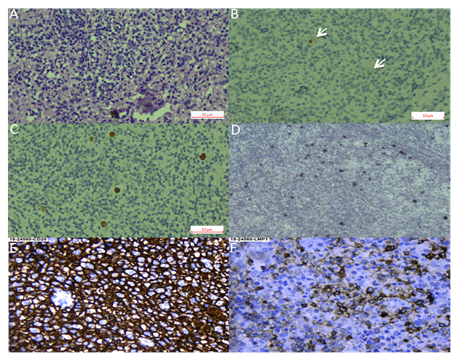

We found 36 studies of HL in LA, including pediatric and adult series from 12 countries. Pediatric series from Argentina exhibited a profile compatible with early cHL (i.e., younger ages, EBV positivity of ~50% and HL-MC as the predominant subtype) [20,25–27], while adult HL displayed a 31% of EBV-association, with similar frequencies of both NS and MC subtypes [22]. On the other hand, in the Southeast of Brazil, EBV positivity was 40–50%, HL-NS was the predominant subtype, and there was a smooth peak between adolescents and young adults, [38,41–45,47,52,58,60,66–70,73], which may suggest a transition state in the epidemiology of the disease presentation between the ones observed in developing and developed areas. Indeed, one study in the most affluent Brazilian State (Sao Paulo) reviewed 817 cases of cHL over 54 years (1954–2008), describing that EBV-positive cases showed a decrease from 87% to 46% during the time of the study, with a remarkable decrease in young adults (85% to 32%) [32]. Nevertheless, HL-NS was still the predominant subtype in all periods. On the contrary, HL in the North of Brazil exhibits high EBV association (87%), HL-MC and young age predominance [61]. These results support the hypothesis that the socioeconomic level may determine the presentation features of this neoplasm, also highlighting the role of EBV as an HL driver that is also influenced by socioeconomic factors. Figure 1A–D shows examples of EBV positive HL-NS and HL-MC.

Figure 1. Hodgkin lymphoma. (A–C). Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma. (A). Hematoxylin-Eosin staining. (B). CD30 staining with arrows pointing at positive Reed-Sternberg cells. (C). Epstein–Barr virus-encoded small RNAs (EBER) in situ hybridization. (D). EBER in situ hybridization of a mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma, magnification 40×. (E,F). Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, magnification 40×. (E). CD30 staining. (F). LMP1 (latent membrane protein 1) staining.

There is only one large pediatric cohort of 42 cases published from Mexico, with a median age of 5 yrs at diagnosis, and in which a male predominance (2.5:1) was observed [78]. EBV positivity was found in 76.1% of the cases and the HL-MC subtype was the most predominant (71.4%). Other studies from Mexico mostly include young and older adults, with scarce inclusion of children and adolescents, and in which EBV association frequencies vary between 61% and 77%. In those studies, a predominance of HL-MC and HL-NS subtypes was observed [82,87–89,118]. In these Mexican studies, a high EBV association was also observed for the lymphocyte depleted (HL-LD) subtype, with 91.2% positive cases [87–89].

In line with the above-described data, a 94% of EBV association was observed in pediatric HL in Peru [108], while in Colombia, EBV association varied from 60% in adults to 84% in children [93,94]. Another study from Honduras that included 11 children younger than 15 yo also found 100% EBV positivity [115]. Series of studies from the Caribbean and continental Central American countries: Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic found intermediate EBV association frequencies (50%, 55%, 36–40% and 64%, respectively), [90,91,110,116–118], which are closer to the frequencies observed in the more developed Argentina. These frequencies should be confirmed with more samples and up-to-date techniques.

2.1.2. Burkitt Lymphoma

BL is a highly aggressive B cell lymphoma, characterized by the translocation of the MYC oncogene to the immunoglobulin loci. It affects mostly children and is also more predominant in males [124]. EBV-associated BL conforms almost 100% of endemic BL and around 20% of sporadic cases of North America and Europe. Other regions of the world, especially developing populations, exhibit intermediate frequencies, such as 50–70% in North Africa and Russia [125][3,125]. Pediatric BL in Argentina has an EBV association frequency closer to the sporadic subtype (25–47%), and the highest incidence of EBV-positive cases is in children younger than 5 yo [14,16,24,28]. As with HL, the frequency of EBV positive cases increase with latitude in Brazil, being ~60% in the South East ,[37,55,56,62–64], and 73–87% in North East [72,74]. A study including an extensive number of BL cases from five Brazilian geographic regions confirmed this trend, disclosing EBV association frequencies from 29% in the South to 76% in the North [53,54]. This pattern appears to represent a socio-geographic gradient, which might reflect social development, as well as other unknown environmental, ethnic or genetic factors [63]. A Brazilian study of 14 population-based cancer registries showed that the global age-adjusted incidence rate for pediatric BL does not differ significantly from the expected for a sporadic BL region. However, the incidence was elevated for BL children aged 1–4 years [126]. Given the association of EBV positive BL with young age, it is tempting to ascribe this elevated risk to the early EBV seroconversion, which is characteristic of the natural history of EBV infection in our geographic region [127]. Indeed, an EBV-associated BL inverse correlation with age has been shown in other studies from Brazil [56] and Argentina [14]. Unfortunately, we could not find reports on BL series from the Andean and Caribbean regions of LA, which, most probably, does not represent a low frequency of this lymphoma there. Although there are studies including BL from Mexico, they do not address EBV infection, and there is only one case report from a 63 yo male with an EBV positive intraoral BL [128].

2.1.3. Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma

DLBCL is a highly aggressive neoplasm that can arise in almost any location of the body. It is very rare in pediatric patients and young adults, but is one of the most common NHLs in older individuals. Due to the median age of presentation of 70 yrs, it is usually associated with underlying immunosuppression. In the former 2008 WHO classification [129], EBV-positive DLBCL of the elderly (> 50 years) was recognized as a provisional entity among the DLBCL subtypes. This provisional entity represented 5–11% of the DLBCL among immunocompetent East Asian patients [130], while in Western populations, the frequency was lower than 5% [131][81,131]. The reported series from LA have shown slightly higher EBV association frequencies (7% México, 9% Brazil, 13% Argentina and 14–28% Peru) [10–12,34,81,95,100,101] than the observed in Western countries [81]. LA patients are also younger than the ones described in other series [11,81]. Peru is particularly interesting, since it has the highest incidence of positive EBV DLBCLs, in addition to the incidence of DLBCL being the highest reported, accounting for up to 45% of all lymphomas [132][100,101,132]. In a Peruvian study of five cases, DLBCL of the gastrointestinal tract was consistently associated with EBV infection in elderly patients [98]. Remarkably, a series of cases of DLBCL of the palatine tonsils from Salvador de Bahia Brazil did not find an association with EBV [40]. Figure 1E,F shows an example of an EBV positive DLBCL.

In the 2016 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms, the age factor was eliminated from the association of EBV with DLBCL, leading to the substitution of the modifier “elderly” with “not otherwise specified” (EBV-positive DLBCL, NOS) [9]. Therefore, new studies free from the restraint of the age limit are needed, to better characterize the magnitude of this association, as well as the prognostic impact of EBV positivity in LA patients. DLBCL are also distinguished by their phenotype as germinal center or activated, with the former exhibiting an overall better survival rate. No differences were found in a series of Argentinian cases with respect to EBV positivity in these two subtypes of DLBCL [11,95].

2.1.4. T and NK Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Although EBV tropism is mainly of B cells and in healthy individuals exclusively localizes in B cells [133], the revised 2016 WHO classification recognizes the chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV) of T/NK cell type, the aggressive NK-cell leukemia, the systemic T-cell lymphoma of childhood and the extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTCL), as well as a new provisional entity, the primary EBV-positive nodal T/NK-cell lymphoma [134][9,134]. These neoplasms represent a broad spectrum of diseases that occur with higher incidence in Asian populations, and, in which, CAEBV, the aggressive NK leukemia and the systemic T-cell lymphoma are more prevalent in children and adolescents, while ENKTCL mainly affects adults [134][9,134]. How the virus infects T or NK cells is still a matter of debate, but exists some evidence of a preferential tropism for T cells for the EBV-2 subtype [135][136][135,136].

CAEBV corresponds to a group of reactive LPDs associated with a heightened EBV infection lasting longer than IM, and with the potential to progress to a systemic lymphoma. The clinical picture is diverse and includes the indolent, localized cutaneous form hydroa vacciniform-like LPD (HVL-LPD), renamed by the revised 2016 WHO classification [9]. Several series of patients with HVL-LPD have been described in LA indicating a high incidence of this disease, mainly in countries with a large Amerindian population component, such as Mexico, [77,84], Bolivia [84], Peru [97,103,105] and Ecuador [109]. In Brazil, two HVL-LPD cases were reported in children from Amazon indigenous tribes, supporting the ethnic bias of this disease [31,39]. In these series of patients, the association with EBV was virtually 100%. These studies have also greatly contributed to illustrate the clinical and pathological features of this disease in LA as an LPD with 70% of cases being of T-cell origin and 30% of NK origin. This scenario is more similar to Asian CAEBV, since, in the US, CAEBV is very rare, and also presents as a B cell LPD [137]. Although cellular and viral monoclonality has been proven in the majority of T-cell cases, the disease is today considered an LPD, with a high risk to progress into a systemic lymphoma [77], to reflect the diverse clinical spectrum of the disease presentation, from self-limited HV to HV-like lymphoma, and also to allow for more adequate therapeutic approaches, since patients respond well to immunomodulatory agents as first line of treatment [77,103,105].

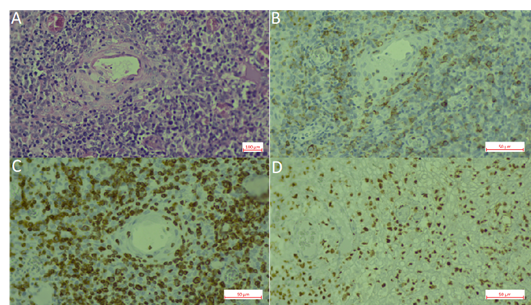

Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (ENKTCL) is an EBV-positive lymphoma more commonly derived from NK cells. Similar to CAEBV lymphoproliferations, this type of lymphoma has been described mainly in East Asia and LA, in which the ethnic composition includes a high proportion of Amerindians. EBV infection is also confirmed in virtually all cases. Series of cases have been reported from México [83], Peru, [104,106], Chile [104,106,112,113] and Guatemala [120]. In Brazil, ENKTCL usually occurs as isolated cases [71]. Recently, a large series was reported that included 122 cases with mostly adults (only three children) from all five Brazilian regions [46]. In this Brazilian cohort, the clinico-pathological characteristics of the neoplasm were similar to the ones described in patients from East Asia and other American countries, in which the disease is considered endemic. No ethnic data was recorded for the patients included in the study. In a Brazilian unicentric study that included lymphomas involving the midline facial region, 16 were of T/NK cell origin and nine were of B cell origin (n = 25). Remarkably, no ethnic differences were found between the patients with T/NK or B cell presentation [71]. Figure 2 shows an example of an ENKTCL.

Figure 2. Extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKL). (A). Hematoxylin-Eosin staining. (B). CD56 staining. (C). CD3 staining. (D). EBER in situ hybridization.