Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Shuang Song.

Lycium barbarum, also named Goji berry, Gouqizi, and wolfberry, is a perennial shrubbery of Solanaceae that is widely cultivated in China, Japan, Korea, North America, and Europe. Lycium barbarum polysaccharides (LBPs) have attracted increasing attention due to their multiple pharmacological activities and physiological functions. The elucidation of precise structures of LBPs is the prerequisite to unraveling the relationships between structures and functions.

- Lycium barbarum polysaccharides

- structural characteristics

- gut microbiota

- immunity

1. Introduction

The human gut microbiota is a complex and abundant community composed of up to 1014 microorganisms with about 1150 species [1]. The community is dominated by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which account for more than 80–90%, and then followed by Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Fusobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Spirochaetes as minor components [2]. The gut microbiota is regarded as a neglected human organ to some extent in the human–microbe superorganism [3]. Furthermore, the dysbiosis of gut microbiota not only affects the host physiological functions (e.g., nutrient digestion, absorption, and metabolism), but triggers diseases (e.g., immune dysregulation responses and metabolic syndrome) [4,5,6][4][5][6]. Therefore, the balance of gut microbiota, including microbial diversity, richness, composition, and functionality, is critical for the health of the host. Numerous studies have demonstrated that several factors, such as genetics, antibiotics, age, and diet, can influence the gut microbiome [6,7][6][7]. Among these factors, a short-term diet can lead to significant microbial changes. More importantly, non-digestible polysaccharides can be degraded and utilized by gut microbiota instead of the host, which encode the carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes), such as glycoside hydrolases (GHs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), glycosyltransferases (GTs) and carbohydrate esterases (CEs), thereby improving beneficial metabolites (e.g., SCFAs) [8,9][8][9].

Lycium barbarum, also named Goji berry, Gouqizi, and wolfberry, is a perennial shrubbery of Solanaceae that is widely cultivated in China, Japan, Korea, North America, and Europe [10]. Currently, China is the largest supplier in the world, and a majority of L. barbarum fruits are distributed in the northwest regions of China, such as Ningxia, Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, and Gansu [11,12][11][12]. Notably, L. barbarum fruits from Ningxia region are the only species included in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China for many years due to their excellent quality [13]. Various bioactive constituents have been isolated and identified from L. barbarum fruits, including polysaccharides, carotenoids, vitamins, flavonoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, anthocyanins, and organic acids. Among them, the polysaccharides, accounting for 5–8% of dried fruits, have been recognized one of the principal active components [10]. In recent decades, a great deal of research has now confirmed that L. barbarum polysaccharides (LBPs) have various biological functions, such as immunoregulation, anti-inflammation, anti-tumor activities, hypoglycemic/lipidemic activities, and retinal protection [14,15,16,17,18,19][14][15][16][17][18][19]. LBPs mainly include arabinogalactans, acidic heteropolysaccharides, glucans, and other polysaccharides [20,21,22,23,24][20][21][22][23][24]. Increasing evidence suggests that the molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, and glycosidic linkage of LBPs could influence their bioactivities, although the structure–activity relationship of polysaccharides is not yet clear. Therefore, elucidating the structures of LBPs would be beneficial to understand the mechanisms of their health effects and further develop their industrial application. However, many studies have shown that most LBPs are resistant to human digestive enzymes and can almost entirely reach the colon where they are digested and metabolized by gut microbiota, indicating that gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the beneficial effects of LBPs [25,26][25][26]. Currently, although the extraction, purification, structural characterization, and functional activities of LBPs have been summarized and reviewed [27[27][28][29],28,29], few reviews have discussed their structural types and summarized the modulation of LBPs on gut microbiota and the role of gut microbiota in the health effects of LBPs, as well as their potential mechanism based on their structural types.

2. Isolation and Structure of LBPs

The elucidation of precise structures of LBPs is the prerequisite to unraveling the relationships between structures and functions. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the biological activities of LBPs are principally related to their primary and advanced structures [10,28][10][28]. Actually, the current studies mainly focus on the primary structures of LBPs due to the limitations of techniques and analysis. The primary structure characterization of LBPs covers molecular weight, types and ratios of monosaccharides, positions of glycosidic linkages, anomeric carbon configuration, and branched chains, which influence their biological activities to varying degrees [18,24][18][24]. Herein, the research progress on the extraction, purification, and structure of LBPs were summarized below.2.1. Extraction and Purification

The isolation principle of LBPs is to keep the properties of polysaccharides unaltered during the procedure of extraction and purification. Based on this principle, several extraction methods for crude LBPs have been developed, which include cold or hot water extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, ultrasonic-assisted extraction, and supercritical fluid extraction [10,27][10][27]. Indeed, water extraction is the most commonly used method to obtain crude LBPs due to its convenient operation and high yield [27,30][27][30]. For example, high molecular weight polysaccharides were obtained from dried wolfberries using cold water extraction in a yield of 2–3%, however, the yields of the polysaccharides could be further improved by prolonged high-temperature extraction or enzymatic treatment [30]. Furthermore, it demonstrated that a ratio of water to raw material 31.2, temperature 100 °C, time 5.5 h, and number of extraction 5 were the optimal extraction conditions to obtain LBPs using the Box–Behnken statistical design (predicted yield 23.13%), which was verified by validation experiments (real yield 22.56 ± 1.67%) [31]. Given the excellent solubility of LBPs in water, several scholars have argued that the increased LBPs contain more pectic, cellulose, and hemicellulosic polysaccharides by extended treatments, such as high temperature, enzymatic treatment, and microwave-assisted treatments [31,32][31][32]. Generally, the water-soluble extracts using the above extraction methods contain many impurities, such as inorganic salts, pigments, monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, and proteins, which interfere with the structure determination of LBPs. Therefore, effective measures have to be adopted to further purify the above crude LBPs. Hydrogen peroxide, as a chemical reagent, is widely applied in depigmentation and the Sevag method is frequently applied in deproteinization for their simple procedures [33]. Subsequently, the methods for LBP purification can be performed by membrane separation (e.g., ultrafiltration and microfiltration), column chromatography (e.g., gel filtration chromatography, ion-exchange chromatography, affinity chromatography, and cellulose column chromatography), and chemical precipitation (e.g., fractional precipitation with ethanol) alone or in combination [27,33][27][33]. Of note, column chromatography is most commonly used in these methods [27]. As we prevFiously reported, five arabinogalactan fractions (LBP1~5) from crude LBPs (extracted by water at room temperature) were separated by DEAE-cellulose chromatography [34]. Afterwards, LbGp1 with a molecular weight of 49.1 kDa was isolated and purified from LBP1 by Sepharedax G-100 column chromatography in yields of 0.018% [22]. Similarly, another five fractions (LRP1, LRP2, LRP3, LRP4, and LRP5) were also isolated from crude L. ruthenicum polysaccharides (extraction by 70 °C water) on DEAE-Cellulose-52 anion-exchange column followed by gradient elution in our one previous studies [35]. Subsequently, LRGP1 (Mw 56.2 kDa) and LRGP3 (Mw 75.6 kDa) were further purified on Sephadex G-100 column in yields of 0.003% and 0.008%, respectively [35,36][35][36]. Moreover, LBP3b (Mw 5 kDa) was purified from crude LBPs extracted with hot water (60 °C) using DEAE-cellulose column and Sephadex G-150 column, which was identified as glucan [24]. In addition, a novel arabinogalactan LBP1A1-1 (Mw 45 kDa) was purified from L. barbarum on DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow column and Sephacryl S-200 HR column in yields of 0.1% [37]. These studies have indicated that the polysaccharide fractions purified by column chromatography are difficult to investigate for the activities in vivo, as well as the structure–function relationship due to low yield and complex operation. Then, we one group developed fractional precipitation with 30%, 50%, and 70% (V/V) ethanol to purify arabinogalactan in yields of 0.38%, which was simpler and more efficient than column chromatography [17].2.2. Structure of LBPs

To date, LBPs have been identified as glycoconjugates that mainly consist of five major structural elements: arabinogalactan, pectin polysaccharide, glucan, xylan, and other heteropolysaccharides [21,22,23,24][21][22][23][24]. Their hypothetical structure features, such as monosaccharide composition, repeat unit, and molecular weight, were summarized in Table 1. Additionally, the molecular weight of LBPs is highly subject to the origin, cultivar, and extraction method, ranging from 5 kDa to 2300 kDa [10,24,38][10][24][38].Table 1.

Molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, and hypothetic structure of LBPs.

| No. | Name | Mw (kDa) | Molar Ratio | Possible Structure of Repeat Unit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LBGP70-OL | 73 | Ara:Gal = 1.0:1.0 | Backbone: (1→6)-β-Galp; branches: (1→3)-α-Araf, (1→3)-β-Araf, (1→5)-β-Araf, (1→3)-β-Galp | [39] |

| 2 | LBP-3 | 67 | Ara:Gal = 1.0:1.6 | Backbone: (1→3)-β-Galp; branches: α-(1→3)-Araf, α-(1→4)-Araf, α-(1→5)-Araf and β-(1→6)-Galp | [40] |

| 3 | LBP-W | 113 | Ara:Gal:Rha = 55.6:35.5:8.0 | Backbone: (1→6)-β-Galp; branches: (1→3)-α-Rhap, (1→3)-β-Galp, (1→3)-α-Araf, (1→5)-α-Araf | [41] |

| 4 | LBP1A1-1 | 45 | Ara:Gal:Glc:Rha = 47.8:49.8:1.4:1.2 | Backbone: (1→3)-β-Galp, (1→6)-β-Galp and (1→4)-β-Glcp; branches: (1→6)-β-Galp on C-3 or (1→3)-β-Galp on C-6. | [37] |

| 5 | LBP1B-S-2 | 80 | Ara:Gal:Glc:Rha = 53.6:39.4:4.0:3.1 | Backbone: (1→3)-β-Galp and (1→6)-β-Galp; branches: (1→4)-β-GlcpA, (1→6)-β-Galp, (1→5)-α-Araf | [42] |

| 6 | LBLP5-A-OL1 | 71 | Ara:Gal:Rha = 1.0:1.2:0.1 | Backbone: (1→3)-linked Galp; branches: (1→6)-linked Galp, (1→3)-linked Galp, (1→3)-linked Araf, (1→4)-linked Araf, (1→5)-linked Araf, and (1→2,4)-linked Rhaf | [43] |

| 7 | LBPA | 470 | Ara:Gal:GlcA:Rha = 9.2:6.6:1.0:0.9 | Backbone: (1→6)-β-d-Galp; branches: (1→3)-α-Araf, (1→5)-α-Araf, (1→6)-β-GlcpA, (1→4)-α-Rhap | [44] |

| 8 | LbGp1 | 49 | Ara:Gal = 5.6:1.0 | Backbone: (1→ 6)-β-Galp; branches: (1→2)-linked Araf, (1→3)-linked-Araf, (1→3)-linked Galp, and (1→4)-linked Galp | [22] |

| 9 | LRGP3 | 76 | Ara:Gal:Rha = 14.9:10.4:1.0 | Backbone: (1→3)-β-d-Galp; branches: (1→5)-α-Araf, (1→2)-α-Araf, (1→6)-β-Galp, (1→3)-Galp, and (1→2,4)-α-Rhap | [36] |

| 10 | LRGP1 | 56 | Ara:Gal:Glc:Rha:Man:Xyl = 10.7:10.4:1.0:0.7:0.7:0.3 |

Backbone: (1→3)-linked Gal; branches: (1→2)-linked Ara, (1→5)-linked Ara, (1→3)-linked Gal, (1→4)-linked Gal, (1→6)-linked Gal, and (1→2)-linked Rha | [35] |

| 11 | AGPs | ND | Gal:Ara:GlcA:Rha:GalA 44.3: 42.9:7.0 3.3:2.4 |

Backbone: (1→3)-β-d-Galp; branches: (1→5)-α-Araf, T-α-Araf, T-β-Araf, T-α-Rhap, and T-β-GlcpA | [45] |

| 12 | WSP1 | ND | Ara:Gal:Glc:HexA:Xyl:Rha:Man = 51.4:25.9:7.3:7.4:4.8:1.6:1.2: | Backbone: (1→3)-Galp; branches: Araf and Galp substituted on O-6 | [46] |

| 13 | LbGp4 | 215 | Gal:Ara:Rha:Glc =2.5:1.5:0.43:0.23 | Backbone: (1→4)-β-Gal; branches: (1→3)-β-Gal with T-α-Ara-(1→ and T-β-Rha-(1→ | [47] |

| 14 | LbGp2 | 68 | Ara:Gal = 4:5 | Backbone: (1→6)-β-Galp; branches: (1→3)-β-Araf and (1→3)-β-Galp with T-α-Araf-(1→ | [48] |

| 15 | LbGp4-OL | 181 | Ara:Gal:Rha = 1.3:1.0:0.1 | Backbone: (1→4)-linked Galp; branches: (1→3)-β-Galp, (1→3)-α-Rhap, (1→3)-β-Araf, (1→5)-β-Araf | [49] |

| 16 | LbGp1-OL | 40 | Ara:Gal = 1:1 | Backbone: (1→6)-β-Galp; branches: (1→3)-β-Galp, (1→3)-β-Araf, and T-α-Araf-(1→ | [50] |

| 17 | LbGp3 | 93 | Ara:Gal = 1:1 | Backbone: (1→4)-β-Galp; branches: (1→3)-β-Araf and (1→3)-α-Galp with T-α-Araf-(1→ | [51] |

| 18 | LBPA3 | 66 | Ara:Gal = 1.2:1.0 | Heteropolysaccharide with (1→4), (1→6)-β-linkage. | [52] |

| 19 | p-LBP | 64 | GalA:Ara:Gal:Rha:Glc:GlcA:Xyl: Fuc = 137.0:54.8:23.0:6.4:4.1:3.4:3.0: 1.0 | Backbone: (1→4)-α-GalpA; branches: (1→2)-α-Rhap on C4 and (1→3)-β-Galp on C-6 | [23] |

| 20 | WSP2 | ND | GalA:Ara:Gal:Xyl:Glc:Rha = 76.0:12.3:6.3:1.8:1.5:1.4 | (1→4)-GalpA | [46] |

| 21 | LBP-1 | 2250 | GalA:Ara:Man:Rha:Gal:Xyl = 8.2:7.9:3.0:1.0:0.7:0.4 |

Backbone: α-(1→5)-l-Ara and α-(1→4)-d-GalA; branches: →1)-Man-(3→6) and T-Man-(1→ | [38] |

| 22 | LBP3a-1/2 | 103/82 | GalA | α-(1→4)-GalA | [53] |

| 23 | LBP3b | 5 | Glc:Man:Rha:Xyl:Gal = 28.1:5.5:5.1:1.7:1.0 | β-glucan | [24] |

| 24 | LBP3p | 157 | Glc:Man:Xyl:Rha:Ara:Gal = 2.1:2.0:1.8:1.3:1.1:1.0 | β-d-Glc linkage | [54] |

| 25 | LBP1a-1/2 | 115/94 | Glc | α-(1→6)-d-glucan | [53] |

| 26 | LBPC4 | 10 | Glc | α-(1→4) (1→6)-glucan | [55] |

| 27 | LBPC2 | 12 | Xyl:Rha:Man = 8.8:2.3:1.0 | Heteropolysaccharide with (1→4) (1→6)-β-linkage | [55] |

| 28 | CWM-4M KOH | ND | Xyl:Ara:HexA:Glc:Gal:Man:Rha = 31.9:19.1:18.0:15.1:10.1:4.8:1.8 |

(1→4) xylan | [46] |

| 29 | LBP-IV | 420 | Glc:Ara:Xyl:Rha:Gal = 7.5:3.8:3.4:1.6:1.0 |

Backbone: α/β-Ara/Glc; branches: T-Rha | [56] |

| 30 | LBP | ND | Glc:Man:Rha:Gal:Ara:Xyl = 6.5:2.2:0.8:0.2:0.2:0.1 | ND | [26] |

Abbreviations: Gal, galactose; Glc, glucose; Rha, rhamnose; Man, mannose; Ara, arabinose; Xyl, xylose; GalA, galacturonic acid; GlcA, glucuronic acid; HexA, hexuronic acid; ND: not detect. Among the above numbers, No.1–No.18 belong to arabinogalactan; No.19–No.22 belong to pectin type; No.23–No.26 belong to glucan type; No.27–No.28 belong to xylan type; No.29–No.30 belong to other type.

2.2.1. Arabinogalactans

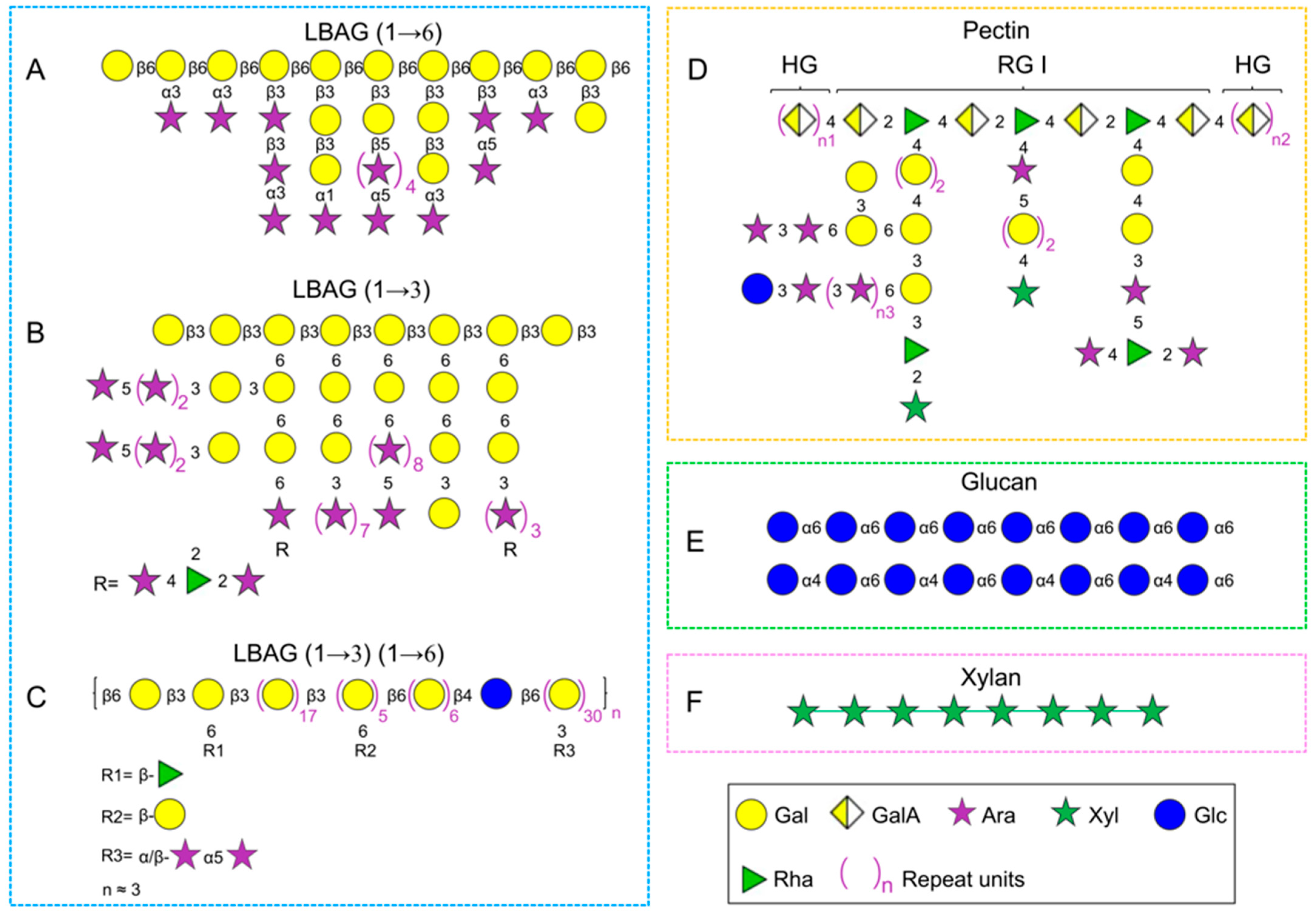

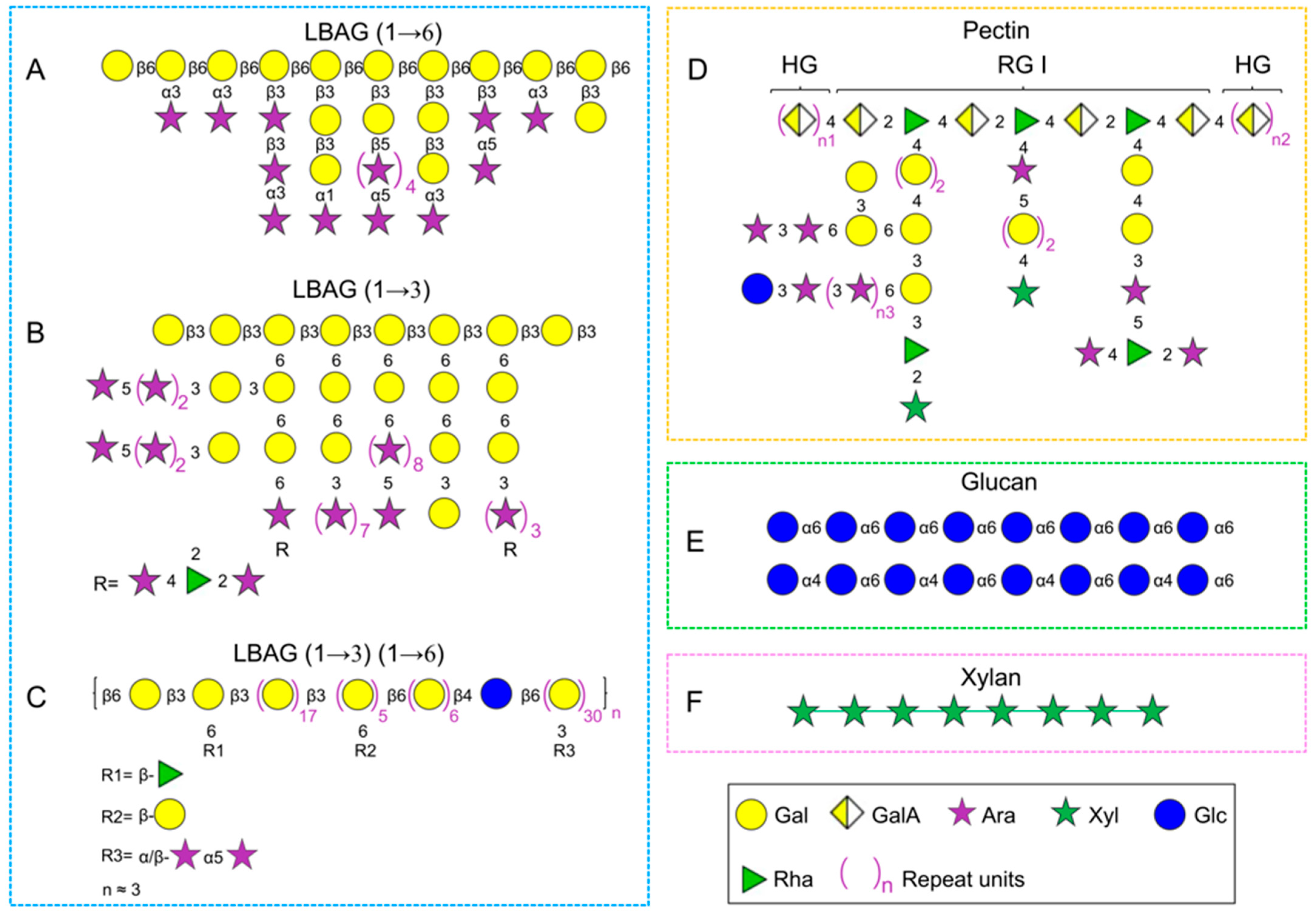

Structural characterization of L. barbarum arabinogalactan-protein has been investigated by multiple research groups, and it has been demonstrated that there are a large number of →3,6)-Galp-(1→ residues based on the methylation analysis. The current controversies about its structure are as follows: (1) L. barbarum arabinogalactan is composed of →6)-β-Galp-(1→ as the backbone, and large amounts of α/β-Araf as branch chains which substituted at C-3 [22,41,48][22][41][48] (Figure 1A); (2) it is a highly branched polysaccharide with a backbone of →3)-β-Galp-(1→ substituted at C-6 with Araf [40,45][40][45] (Figure 1B); (3) the fraction possesses both β-(1→6)-linked Galp and β-(1→3)-linked Galp as the backbones with partial substitution at the C-3 site and C-6 site, respectively [37,42][37][42] (Figure 1C). The backbone structure of arabinogalactan in LBPs may be different due to diverse origin and various isolation methods. As mentioned above, a combination of ion exchange column and gel filtration column chromatography is commonly employed for the purification of arabinogalactan fraction from L. barbarum glycoconjugates; however, it is not suitable for large-scale preparation of arabinogalactan due to complex operation, time-consuming processes, and low yield. Recently, our one research team revisited the structure of L. barbarum arabinogalactan using a set of chemical methods and analytical techniques, including partial acid hydrolysis, methylation analysis, alkaline degradation, monosaccharide composition analysis, 1H and 13C spectroscopy, and ESI-MSn [39] on the basis of the ethanol precipitation method reported [17]. And the results indicated that it was a highly branched polysaccharide with a backbone of →6)-β-Galp-(1→ and branched chains of →3)-β-Glap (1→, →3)-α-Araf-(1→ and →5)-β-Araf-(1→ substituted at the C3 position, which had an average of 9 branches per 10 sugar backbone units. Additionally, the anti-aging activity of L. barbarum arabinogalactan was significantly higher than the backbone fraction (Gal percentage = 91%) obtained by partial acid hydrolysis (0.02 M H2SO4), indicating that the anti-aging activity was closely relevant to the arabinose branched chains. These results implied that the biological activities of LBPs were considerably influenced by their structures, especially branched chains and spatial configuration [39].

2.2.2. Pectins

Pectins, as a cell wall component of plants, are unique polysaccharides comprising predominantly uronic acids, such as glucuronic acid (GlcA) and galacturonic acid (GalA) [57]. The polysaccharides extracted from L. barbarum fruits also contain pectins (Figure 1D). There are mainly three typical structures in pectins: homogalacturonan (HG), rhamnogalacturonan-I (RG-I), and rhamnogalacturonan-II (RG-II) [58,59][58][59]. A typical pectic polysaccharide (p-LBP) with a backbone of →4-α-GalpA-(1→ (HG) and a partial region of →4-α-GalpA-(1→ and →2-α-Rhap-(1 → (RG-I) was isolated and purified using a series of column chromatographies (e.g., macroporous resin S-8, DEAE column and Sephacryl S400 gel permeation) and analytical techniques (e.g., 1H and 13C spectroscopy) [23]. Another acidic polysaccharide (LBP3a) was also separated from the crude extraction by DEAE-cellulose chromatography, which was identified as HG-type pectin with a backbone of →4)-α-D-GalpA(1→ [53]. HG-type pectin was found in the above studies, perhaps due to the same extraction methods (e.g., hot water) and original place. Besides, the polysaccharides from L. barbarum insoluble cell wall material (CWM) dissolved in the CDTA and Na2CO3 solutions contained 76.3% and 51.9% uronic acid, respectively. Notably, the fraction extracted by CWM-Na2CO3 may be RG-type pectin, which was supported by the increased level of rhamnose (Rha) [46]. Additionally, one homogeneous polysaccharide (LBP-1, Mw 2250 kDa) was purified from crude LBPs using DEAE column, whose structure was identified as pectin with a backbone of α-(1→5)-l-Ara and α-(1→4)-d-GalA, and branched chains of →3)-Man-(1→, →6)-Man-(1→, and T-Man-1(→ [38].2.2.3. Glucans

Glucans widely exist in the cell walls of various plants and fungi, and there is a small amount in L. barbarum fruits, despite the diversity in conformation and linkages [60]. For instance, LBP1a-1 (Mw 115 kDa) and LBP1a-2 (Mw 94 kDa) were obtained from crude LBPs using DEAE-cellulose and Sephacryl S-400 HR column chromatography, which was identified as glucan with a backbone of →6)-α-d-Glcp (1→ [53]. Moreover, a homogenous polysaccharide with a molecular weight of 4.9 kDa was separated from crude LBPs by the DEAE-cellulose column in combination with Sephadex G-150 column and then identified as a β-glucan by monosaccharide composition and 1H/13C NMR analysis [24]. In addition, an α-(1→4) (1→6) glucan (LBPC4) was isolated and purified from crude LBPs using DEAE-cellulose column and Sephadex G-50 column [55].2.2.4. Xylans

Xylans are the primary hemicellulose component in plant cells, which are mainly found in hardwood (15–30%), softwoods (7–10%), and annual plants (up to 30%) [61]. Additionally, 4 M KOH-soluble fraction isolated from L. barbarum insoluble cell wall material was a xylan instead of xyloglucan, which was supported by the fact that the xylose content was twice that of the glucose [46]. In addition, a β-(1→4) (1→6)-linked heteropolysaccharide (LBPC2) was separated from crude LBPs using DEAE-cellulose column and Sephadex G-50 column [55]. Interestingly, it was composed of only Xyl, Rha, and Man in a molar ratio of 8.8:2.3:1.0, so LBPC2 was supposed to be a xylan, which needs further confirmation.2.2.5. Other Polysaccharides

Apart from the above four types, the structural elements of LBPs have been identified as other types from their monosaccharide composition in a few studies. For example, LBP-IV, which is mainly composed of Glc, Ara, and Xyl in a molar ratio of 7.54:3.82:3.44, was separated from crude LBPs on the DEAE-Sephadex A-25 column [56]. Another polysaccharide was isolated from crude LBPs with a macroporous resin S-8 column, which primarily comprised Glc, Man, and Rha in molar ratios of 6.52:2.17:0.81 [26]. These results indicate that LBPs contain other heteropolysaccharides in addition to arabinogalactan, pectin, glucan, and xylan; however, the structures need to be further identified and confirmed.References

- Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 2012, 489, 242–249.

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell 2012, 148, 1258–1270.

- Clarke, G.; Stilling, R.M.; Kennedy, P.J.; Stanton, C.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Minireview: Gut microbiota: The neglected endocrine organ. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 1221–1238.

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803.

- Shi, Q.; Dai, L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X. A review on the effect of gut microbiota on metabolic diseases. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 192.

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836.

- Tannock, G.W. Modulating the gut microbiota of humans by dietary intervention with plant glycans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02757-20.

- Koropatkin, N.M.; Cameron, E.A.; Martens, E.C. How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 323–335.

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345.

- Tian, X.; Liang, T.; Liu, Y.; Ding, G.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Z. Extraction, structural characterization, and biological functions of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides: A review. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 389.

- Fukuda, T.; Yokoyama, J.; Ohashi, H. Phylogeny and biogeography of the genus Lycium (Solanaceae): Inferences from chloroplast DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2001, 19, 246–258.

- Jiapaer, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, L.; Shen, Y.; Ye, X. A review of phytochemical composition and bio-active of Lycium barbarum fruit (Goji). Zhongguo Shipin Xuebao 2013, 13, 161–172.

- Pharmacopoeia Commission of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Ming, M.; Guanhua, L.; Zhanhai, Y.; Guang, C.; Xuan, Z. Effect of the Lycium barbarum polysaccharides administration on blood lipid metabolism and oxidative stress of mice fed high-fat diet in vivo. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 872–877.

- Tang, R.; Chen, X.; Dang, T.; Deng, Y.; Zou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Gong, G.; Song, S.; Ma, F.; Huang, L.; et al. Lycium barbarum polysaccharides extend the mean lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4231–4241.

- Gong, G.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Dang, T.; Dai, W.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Arabinogalactan derived from Lycium barbarum fruit inhibits cancer cell growth via cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 639–650.

- Gong, G.; Dang, T.; Deng, Y.; Han, J.; Zou, Z.; Jing, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z. Physicochemical properties and biological activities of polysaccharides from Lycium barbarum prepared by fractional precipitation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 611–618.

- Cheng, J.; Zhou, Z.W.; Sheng, H.P.; He, L.J.; Fan, X.W.; He, Z.X.; Sun, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.J.; Gu, L.; et al. An evidence-based update on the pharmacological activities and possible molecular targets of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 33–78.

- Chang, C.C.; So, K.F. Lycium Barbarum and Human Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015.

- Gao, Z.; Ali, Z.; Khan, I.A. Glycerogalactolipids from the fruit of Lycium barbarum. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 2856–2861.

- Jin, M.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, K.; Shang, P. Biological activities and potential health benefit effects of polysaccharides isolated from Lycium barbarum L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 54, 16–23.

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Mou, Q.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L. Structural characterization of LbGp1 from the fruits of Lycium barbarum L. Food Chem. 2014, 159, 137–142.

- Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Yu, J.; Lu, W.; Pan, C.; Yao, W.; Gao, X. Structure characterization, chemical and enzymatic degradation, and chain conformation of an acidic polysaccharide from Lycium barbarum L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 114–124.

- Tang, H.-L.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.-K.; Sun, G.-J. Biochemical analysis and hypoglycemic activity of a polysaccharide isolated from the fruit of Lycium barbarum L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 77, 235–242.

- Ding, Y.; Yan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Chen, D.; Mi, J.; Lu, L.; Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. In vitro digestion under simulated saliva, gastric and small intestinal conditions and fermentation by human gut microbiota of polysaccharides from the fruits of Lycium barbarum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 751–760.

- Zhou, F.; Jiang, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, H. Lycium barbarum polysaccharide (LBP): A novel prebiotics candidate for Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1034.

- Masci, A.; Carradori, S.; Casadei, M.A.; Paolicelli, P.; Petralito, S.; Ragno, R.; Cesa, S. Lycium barbarum polysaccharides: Extraction, purification, structural characterisation and evidence about hypoglycaemic and hypolipidaemic effects. A review. Food Chem. 2018, 254, 377–389.

- Wu, D.; Guo, H.; Lin, S.; Lam, S.; Zhao, L.; Lin, D.; Qin, W. Review of the structural characterization, quality evaluation, and industrial application of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 79, 171–183.

- Amagase, H.; Farnsworth, N.R. A review of botanical characteristics, phytochemistry, clinical relevance in efficacy and safety of Lycium barbarum fruit (Goji). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1702–1717.

- Bucheli, P.; Gao, Q.; Redgwell, R.; Vidal, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W. Biomolecular and clinical aspects of Chinese wolfberry. In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects; Benzie, I.F.F., Wachtel-Galor, S., Eds.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011.

- Yin, G.; Dang, Y. Optimization of extraction technology of the Lycium barbarum polysaccharides by Box–Behnken statistical design. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 603–610.

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. Study on structure of Lycium barbarum L. polysaccharide. Food Res. Dev. 2007, 28, 74–77.

- Ren, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, W.; Del Rio Flores, A. The preparation and structure analysis methods of natural polysaccharides of plants and fungi: A review of recent development. Molecules 2019, 24, 3122.

- Huang, L.; Lin, Y.; Tian, G.; Ji, G. Isolation, purification and physico-chemical properties of immunoactive constituents from the fruit of Lycium barbarum L. Yao Xue Xue Bao 1998, 33, 512–516.

- Peng, Q.; Lv, X.; Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Du, Y. Isolation and structural characterization of the polysaccharide LRGP1 from Lycium ruthenicum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 95–101.

- Peng, Q.; Song, J.; Lv, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Du, Y. Structural characterization of an arabinogalactan-protein from the fruits of Lycium ruthenicum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9424–9429.

- Zhou, L.; Liao, W.; Chen, X.; Yue, H.; Li, S.; Ding, K. An arabinogalactan from fruits of Lycium barbarum L. inhibits production and aggregation of Aβ(42). Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 195, 643–651.

- Zou, S.; Zhang, X.; Yao, W.; Niu, Y.; Gao, X. Structure characterization and hypoglycemic activity of a polysaccharide isolated from the fruit of Lycium barbarum L. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 1161–1167.

- Huang, W.; Zhao, M.; Wang, X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Gong, G.; Huang, L. Revisiting the structure of arabinogalactan from Lycium barbarum and the impact of its side chain on anti-ageing activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 119282.

- Wu, J.; Chen, T.; Wan, F.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Ma, L. Structural characterization of a polysaccharide from Lycium barbarum and its neuroprotective effect against β-amyloid peptide neurotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 176, 352–363.

- Yang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Kang, Z.; Wu, M.; Yin, H.; Duan, J. A homogeneous polysaccharide from Lycium barbarum: Structural characterizations, anti-obesity effects and impacts on gut microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 2074–2087.

- Zhou, L.; Huang, L.; Yue, H.; Ding, K. Structure analysis of a heteropolysaccharide from fruits of Lycium barbarum L. and anti-angiogenic activity of its sulfated derivative. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 47–55.

- Gong, G.; Fan, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Isolation, structural characterization, and antioxidativity of polysaccharide LBLP5-A from Lycium barbarum leaves. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 314–324.

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y.-B.; Jiang, Y.; Prasad, K.N.; Yang, J.; Qu, H.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Mo, H.; Yang, B. Structure identification of a polysaccharide purified from Lycium barbarium fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 82, 696–701.

- Redgwell, R.J.; Curti, D.; Wang, J.; Dobruchowska, J.M.; Gerwig, G.J.; Kamerling, J.P.; Bucheli, P. Cell wall polysaccharides of Chinese Wolfberry (Lycium barbarum): Part 2. Characterisation of arabinogalactan-proteins. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 1075–1083.

- Redgwell, R.J.; Curti, D.; Wang, J.; Dobruchowska, J.M.; Gerwig, G.J.; Kamerling, J.P.; Bucheli, P. Cell wall polysaccharides of Chinese Wolfberry (Lycium barbarum): Part 1. Characterisation of soluble and insoluble polymer fractions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 1344–1349.

- Peng, X.-M.; Huang, L.-J.; Qi, C.-H.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Tian, G.-Y. Studies on chemistry and immuno-modulating mechanism of a glycoconjugate from Lycium barbarum L. Chin. J. Chem. 2010, 19, 1190–1197.

- Peng, X.; Tian, G. Structural characterization of the glycan part of glycoconjugate LbGp2 from Lycium barbarum L. Carbohydr. Res. 2001, 331, 95–99.

- Huang, L.; Tian, G.; Qi, C.; Zhang, Y. Structure elucidation and immunoactivity studies of glycan of glycoconjugate LbGp4 isolated from the fruit of Lycium barbarum L. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2001, 22, 407–411.

- Chunhui, Q.; Linjuan, H.; Yongxiang, Z.; Xiunan, Z.; Gengyuan, T.; Xiangbin, R. Chemical structure and immunoactivity of the glycoconjugates and their glycan chains from the fruit of Lycium barbarum L. Chin. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 15, 185–190.

- Huang, L.J.; Tian, G.Y.; Ji, G.Z. Elucidation of glycan of glycoconjugate LbGp3 isolated from the fruit of Lycium barbarum L. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 1999, 1, 259–267.

- Zhao, C.; Li, R.; He, Y.; Chui, G. Studies on the chemistry of Gouqi polysaccharides. J. Beijing Med. Univ. 1997, 29, 231–232, 240.

- Duan, C.L.; Qiao, S.Y.; Wang, N.L.; Zhao, Y.M.; Yao, X.S. Studies on the active polysaccharides from Lycium barbarum L. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2001, 36, 196–199.

- Gan, L.; Zhang, S.H.; Liu, Q.; Xu, H.B. A polysaccharide-protein complex from Lycium barbarum upregulates cytokine expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 471, 217–222.

- Zhao, C.; He, Y.; Li, R.; Cui, G. Chemistry and pharmacological activity of peptidoglycan from Lycium barbarum L. Chin. Chem. Lett. 1996, 7, 1009–1010.

- Liu, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, A. Polysaccharides from Lycium barbarum leaves: Isolation, characterization and splenocyte proliferation activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 417–422.

- Anderson, C.T. Pectic polysaccharides in plants: Structure, biosynthesis, functions, and applications. In Extracellular Sugar-Based Biopolymers Matrices; Cohen, E., Merzendorfer, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 487–514.

- Luis, A.S.; Briggs, J.; Zhang, X.; Farnell, B.; Ndeh, D.; Labourel, A.; Baslé, A.; Cartmell, A.; Terrapon, N.; Stott, K.; et al. Dietary pectic glycans are degraded by coordinated enzyme pathways in human colonic Bacteroides. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 210–219.

- Ndeh, D.; Rogowski, A.; Cartmell, A.; Luis, A.S.; Baslé, A.; Gray, J.; Venditto, I.; Briggs, J.; Zhang, X.; Labourel, A.; et al. Complex pectin metabolism by gut bacteria reveals novel catalytic functions. Nature 2017, 544, 65–70.

- Colosimo, R.; Mulet-Cabero, A.-I.; Cross, K.L.; Haider, K.; Edwards, C.H.; Warren, F.J.; Finnigan, T.J.A.; Wilde, P.J. β-glucan release from fungal and plant cell walls after simulated gastrointestinal digestion. J. Funct. Food. 2021, 83, 104543.

- Prade, R.A. Xylanases: From biology to biotechnology. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 1996, 13, 101–132.

More