Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jong-Shyan Wang and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

Mitochondria dysfunction is implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Exercise training is potentially an effective non-pharmacological strategy to restore mitochondrial health in CVD.

- exercise

- cardiovascular system

- mitochondrial function

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a health crisis with increasing incidence and prevalence, which may compromise physical performance and contribute to mortality, morbidity, and the economic burden of health care. The prevalence of CVD remains high and is persistently the leading cause of death globally as data shown estimated 17.9 million people died from CVDs in 2019, contributing to 32% of all global deaths [1]. Mitochondria dysfunction is greatly implicated to the pathogenesis and progression of CVD, setting out the emergence of mitochondrial-targeting therapy [2]. As a non-pharmacological tool, exercise training is potentially a safe and effective measure to restore mitochondrial health in CVD [3]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms of exercise on mitochondrial function are not yet elucidated.

Optimal mitochondrial function is fundamentally achieved through the balance of organelle synthesis and degradation in response to energy demand. Under stable conditions, mitochondrial turnover is regulated by the fusion and fission processes. Any damage to the mitochondrial network will recruit fission protein to cleave off the dysfunctional site. The damaged mitochondrial portion will then be cleared by mitophagic degradation, while the functional portion will be fused to other mitochondria. In a high energy-demand state, such as exercise or under hypoxia condition, the rate of mitochondrial biogenesis and turnover is enhanced. Healthy mitochondria consume oxygen and synthesis ATP in the electric transport chain with an efficient degradation of the damaged site. However, disruption in mitochondrial turnover were seen in many CVD, namely atherosclerosis, reperfusion injury, and cardiomyopathy [4].

Mitochondrial dysfunction manifested with structural and functional abnormality in the myocardial [5][6][5,6] and skeletal muscles [7]. The metabolic maladaptation of mitochondria in CVD was observed with impaired oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and decreased ATP levels, increased apoptosis, deregulated autophagy, and severe oxidative stress [8][9][8,9]. Endothelial damage induces excessive ROS, which increases the endothelial permeability and monocytes adhesion to the vascular wall, subsequently promoting plague formation [10][11][10,11]. Proinflammation induced by mitochondrial dysfunction triggers plaque rupture, resulting in myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) [12].

Despite the optimal pharmacological treatment, the progression of CVD often results in prognosis and low quality of life. Mitochondria’s role in CVD have been giving novel insights into finding therapeutic ways to fight the disease. However, it is challenging to activate mitochondrial biogenesis without compromising safety, to restore oxidative capacity in cardiomyocyte and vascular cells [2][13][2,13]. Therefore, mitochondria-targeted drug therapy remains elusive. Physical exercise is long known as a cardioprotective factor and reduces mortality. A recent cohort study with 30 years of follow-up revealed that long term physical activity was strongly associated with lower mortality for individuals who performed ≈150 to 300 min/week of vigorous physical activity, 300 to 600 min/week of moderate physical activity, or an equivalent combination of both [14]. Regular exercise reduces cardiovascular risks by down-regulating blood pressure, body weight, and LDL cholesterol, increasing HDL and insulin sensitivity, attenuating inflammation, and more recently, modifies mitochondrial dynamics and function [3].

Animal and pre-clinical studies have been suggesting exercise-induced effects on the mitochondrial life cycle, such as increasing PGC-1α, promoting fusion, enhanced oxygen consumption rate, and increased mitophagy. These benefits are yet to be elucidated in human study. TheOur previous studies demonstrated that moderate-intensity continuous and high-intensity interval exercise regimens improved the mitochondrial functions of platelets and lymphocytes in sedentary individuals [15][16][17][18][15,16,17,18] and in patients with CVD [19][20][21][22][19,20,21,22]. Nevertheless, additional information is needed to understand the exact mechanism of exercise on mitochondrial functionality in patients with CVD [23][24][25][23,24,25]. Moreover, the prescription of exercise, including type, intensity, duration, frequency, and progression, to ameliorate mitochondrial function, remained unclear.

2. Physical Exercise Programs

Eleven studies employed aerobic exercise using a static bike, treadmill, or functional movements, of which three used high intensity interval training (HIIT) [22][26][27][22,42,44]. Eight studies involved resistance exercise, of which only three worked on multiple muscle groups [28][29][30][34,37,38], the others were knee or hand movements. One study explored blood flow restricted knee extension exercise with low intensity [31][32]. Two studies had group training in addition to cycling regimen [32][33][33,45]. The exercise intensity in aerobic training was tailored to participants’ characteristics, based on peak oxygen uptake (% VO2peak, 60%) [19][22][34][19,22,43], the percentage of peak heart rate (%HRpeak, 70~95%) [32][33][33,45], the percentage of maximum heart rate (%HRmax, 70~80%) [26][35][29,42], ventilation threshold (VT) [20], and pain threshold [36][37][38][39,40,41]. The training duration ranged from four to 24 weeks, with a frequency of twice a week to daily. Time per session ranged from 10 to 60 min. Resistance training was performed with free weights or machines. The exercise intensity was tailored to participants’ characteristics, based on Repetition Maximum (RM, ranged 30~80%) [28][29][31][32,34,37], maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC, 15%) [39][35], or maximum work rate (WRmax, 50~100%) [27][40][30,44]. The training duration ranged from 6 to 18 weeks, with a frequency of thrice a week to daily. Each session took 10 to 100 min or 2–3 sets of 8–10 repetitions. In terms of the disease cohorts, five of the 13 HF studies adopted aerobic exercise and the others were resistance exercise. Three studies compared the training effect between patients and healthy control [29][39][40][30,35,37]. Three studies gave advice or no intervention to the control group [22][31][22,32], three continued with usual care, while the others had no control group. Concerning PAD, three of the four studies used functional activities such as walking [36][37][38][39,40,41], calf raises [38][41], or lower limb movement [36][39]. Two studies recruited control group with the usual care/general rehab program [19][20][19,20]. Aerobic exercise was implemented in studies for CVA, coronary artery disease, and hypertension.2.1. Mitochondrial Outcomes

The selected studies performed muscle biopsy, spectroscopy, or venous blood test to evaluate the mitochondria function of skeletal muscle cells or platelets. The majority of the studies performed skeletal muscle biopsy on either vastus lateralis [26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][40][41][30,31,32,33,34,37,38,42,43,44,45] or gastrocnemius [36][38][39,41]. Four studies used spectroscopy to examine skeletal muscle mitochondrial function from the forearm [39][42][35,36] and lower leg [35][37][29,40]. Chou et al. [22], Lin et al. [20], and Hsu et al. [19] had withdrawn venous blood to analyze platelet mitochondrial bioenergetics in patients with HF, CVA, and PAD, respectively.2.1.1. Mitochondrial Morphology

Two studies on patients with HF reported controversial findings on the effect of resistance training in mitochondrial phenotypes. Toth et al. [29][37] showed no change to the muscle mitochondrial size after 18 weeks of moderate-intensity systemic resistance exercise, whereas Santoro et al. [28][34] reported an increase of 23.4% in size with unaltered shape with similar protocol but higher intensity.2.1.2. Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Dynamics

Two studies [40][41][30,31] investigated the effect of resistance training on the mitochondrial volume density in patients with HF and reported significant gain in the mitochondrial volume density. Another two studies [32][33][33,45], examined the effect of aerobic exercise, and also reported significant increase in the mitochondrial volume density. In detail, there were increment in TVVM (19%), the surface density of the mitochondrial inner border membrane—SVMIMB (92%), the surface density of mitochondrial cristae—SVMC (43%), and the surface density of cytochrome c oxidase-positive mitochondria—SVMOCOX+ (between 27 and 41%). In studies that evaluated the protein and enzyme activities contributing to mitochondrial biogenesis, there was no agreement from the selected studies. Two studies [29][34][37,43] showed no change in PGC-1α, whereas Wisløff et al. [26][42] reported a significant increment after 12-week AIT. One study [29][37] reported that Tfam improved significantly after training, while the other [34][43] showed no change. Fiorenza et al. [27][44] reported no change in ERRα after training. The one study [27][44] that investigated the fusion and fission phase reported that MFN1 and OPA1 were down-regulated by HIIT. MFN2 was up-regulated by HIIT but DRP1 had no change.2.1.3. Mitochondrial Oxidative Capacity

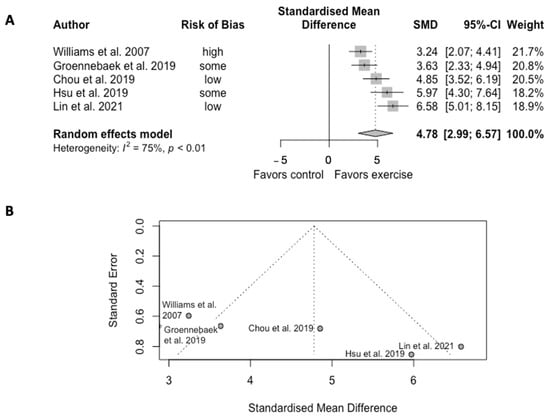

Exercise training significantly increased the mitochondrial oxidative capacity in five trials (SMD = 4.78, CI = 2.99 to 6.57, p < 0.01) (Figure 12). However, the analysis showed high heterogeneity among studies (Q = 16.10, df = 4, p = 0.003, I2 = 75%).

Figure 12. (A) Forest plot of effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals representing oxidative capacity, based on the random effects meta-analysis results. (B) Funnel plots of publication bias. Abbreviation: SMD, standardized mean difference. Williams et al. [30][38], Groennebaek et al. [31][32], Chou et al. [22], Hsu et al. [19], and Lin et al. [20].