Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Amina Yu and Version 1 by Neil Blackstone.

In particular, metabolic or “redox” signaling related to chemiosmosis may have had a major impact on the history of life. Consider the banding together of prokaryotes to form eukaryotes. While there are numerous models for this process, most models converge on several salient points. First, the initial association of lower-level units was based on some sort of syntrophy, i.e., “feeding together”, where the waste of one partner was the substrate for the other. Second, the partner that became the mitochondrion had a functional electron transport chain that it used to carry out chemiosmosis.

- atmospheric oxygen

- chemiosmosis

- eukaryotes

- history of life

- mitochondria

1. From First ECA to LECukaryotic Common Ancestor (FECA) to Last Eukaryotic Common Ancestor (LECA)

What then of the path from FECA to LECA? It may be impossible to precisely discern this pathway, but several considerations can constrain the possibilities. The path from LECA to modern eukaryotes was one of specialization and narrowing of function. How does this proceed? When an organism ceases to use a function, there is no fitness penalty for the loss of genes that influence the underlying functional capacity. Unless these genes are constrained by pleiotropy, they can thus undergo mutational decay without any purifying selection at the organismal level. While some instances of re-derived complex adaptations have been found [22][1], something as complex as the electron transport chain, which only evolved once in the history of life, would seem extremely unlikely to be regained after being lost.

In all likelihood, the protomitochondria that preceded LECA were therefore capable of the full range of bioenergetics found in modern mitochondria, including aerobic metabolism (e.g., Krebs cycle, chemiosmosis) and the combined anaerobic capabilities as well [16][2]. All the mitochondria on the pathway from FECA to LECA must have retained these capabilities. While any particular function may have only been used intermittently, there could not have been long periods of time where some functions were not used at all. In this context, consider the most widely known model for the first steps in eukaryogenesis, the “hydrogen hypothesis” [23][3]. Briefly, in an anaerobic environment, heterotrophic, sometimes aerobic, bacterial protomitochondria carried out glycolysis. As with anaerobic metabolism in general, re-oxidizing NADH was necessary. Here, the protomitochondria did this by converting pyruvate to CO2, H2O, and H2. Essentially, the electrons from NADH were funneled onto protons to make H2 as well as perhaps fatty acids. These protomitochondria formed a syntrophic relationship with autotrophic archaea, which used these waste products so that H2 was now the electron donor and CO2 was reduced to both sugars and methane. The latter was released as waste. In time, the bacterial community became endosymbiotic. While it may seem that the bacteria were initially useful to the archaea but not the converse, i.e., that this was a commensal relationship, when end-product inhibition is considered, the initial advantages to the bacteria become clear, and properly this should be regarded as a mutualistic symbiosis.

Nevertheless, if FECA metabolized only in this way for many generations, other metabolic capabilities of protomitochondria would have been lost via mutation unless there was significant pleiotropy. One may thus surmise that other aspects of this syntrophic relationship developed in parallel, perhaps stemming from day/night alterations in environmental conditions. In the presence of cyanobacterial photosynthesis, for example, molecular oxygen may have been available, and the protomitochondria may have metabolized acetyl CoA via the Krebs cycle and used the electron transport chain to re-oxidize NADH with the electrons reducing molecular oxygen to water. In this way, such pathways could have been utilized, and the full range of functional capabilities ultimately passed down to LECA.

These considerations have implications regarding evolutionary conflict as well. When FECA found itself in a highly favorable environment, oxidative phosphorylation may have been central to its bioenergetics. As suggested by modern aerobic mitochondria, when provided with the necessary materials (e.g., substrate, oxygen, ADP, and phosphate) phosphorylation would be maximal with moderate ROS formation (i.e., “state 3” metabolism of ref. [21][4]). On the other hand, once all of the ADP is converted into ATP, these mitochondria would continue to oxidize substrate until the trans-membrane proton gradient became maximal and the electron carriers were highly reduced (i.e., “state 4” of ref. [21][4]). ROS formation would then become maximal. In this context, uncoupler proteins would be an extremely useful adaptation, harmlessly lowering the proton gradient by returning protons to the matrix. Both uncouplers and ADP/ATP carriers (AAC’s) belong to a well-defined eukaryotic gene family [24][5]. Indeed, the latter seem to have evolved from the former, and AAC’s still function as proton channels [25][6]. For protomitochondria in state 4, uncouplers and AAC’s have a similar effect, one lowering the proton gradient directly, the other bringing in ADP so that the proton gradient could be diminished by making more ATP. It was of course necessary for FECA’s cytoplasm to consume ATP and regenerate ADP and phosphate. In this way, AAC’s had a profound impact on the emerging symbiosis.

Nevertheless, uncouplers and AAC’s require innovation, which inevitably takes time. Co-opting existing bacterial mechanisms to diminish ROS may have preceded such innovation. In this way, many of the signaling pathways that govern eukaryotic cells may have originated at this time as arbiters of evolutionary conflict [15,26][7][8]. Consider for example calcium signaling [27][9]. In eukaryotic cells, calcium signaling is highly versatile and regulates many different functions [28,29][10][11]. By using various pumps, channels, exchangers, and binding proteins, the intracellular concentration of calcium is maintained at a much lower level than that of the extracellular environment. Low intracellular concentrations of calcium are necessary to avoid the precipitation of calcium phosphate. This low intracellular background, however, also allows signaling via pulses or waves of Ca2+ originating from the extracellular environment or intracellular stores. Calcium ions are thus a key “second messenger” in multicellular animals. While many aspects of calcium signaling in modern cells may be more recently derived, the process itself may have roots dating back to FECA. Once protomitochondria became endosymbionts, they began to interact directly with the host and only indirectly with the external environment. For instance, mitochondria could congregate near a calcium channel in the cell membrane. In the presence of substrate, a calcium signal could be energized by mitochondria by taking up and expelling the calcium, while at the same time oxidative phosphorylation would increase and ROS would decrease [15,27][7][9]. If mitochondria were deprived of substrate, however, the calcium signal would not be energized. In this way, under-resourced mitochondria could signal their metabolic state to the host. Calcium ions, along with ROS and ATP, may have been the tools that mitochondria used to communicate with their hosts [30][12]. The many facets of calcium signaling in modern cells may thus be vestiges of this ancient host-symbiont interaction.

If the original syntrophic relationship developed in an aerobic environment at least in part, ROS signaling may have arbitrated conflict from the beginning of the evolutionary transition [7][13]. In a favorable environment with abundant substrate and molecular oxygen, protomitochondria may have phosphorylated at maximal rates, likely outstripping their metabolic demand. As chemiosmotic products built up in protomitochondria, so too would ROS. High levels of ROS may have triggered unspecified mechanisms that led to the export of these products. In this way, the protomitochondria may have continued to phosphorylate maximally, while ROS were maintained at moderate levels. The concentration of these products in the environment may have been a valuable resource for another microbe, which utilized these products. The benefit to the protomitochondria would be two-fold: first, the concentration of raw materials in the environment would increase, allowing easier uptake, and second, the concentration of products in the environment would decrease, facilitating export. A syntrophic relationship between these microbes would quickly develop. Note, however, that the principal benefit to the protomitochondria was simply getting rid of end products in order to rein in high levels of ROS.

In the initial syntrophic relationship, whether based on an aerobic chemiosmosis or the anaerobic hydrogen metabolism, or both, cooperation can be maintained by stoichiometry [26][8]. Neither partner could profit by exporting or importing more or less than their share, since the chemical reactions determine these shares. Once an endosymbiosis was established and ATP became the principal product of mitochondria, however, a mitochondrion could defect from the cooperative relationship by ceasing to export this product, e.g., via loss-of-function mutations. In some environments (e.g., nutrient-scarce ones), this might be selectively neutral or even beneficial. Under conditions of abundant resources, however, defectors that hoard products face the risk of damage or destruction from high levels of ROS and programmed cell death. ROS signaling pathways may thus have arbitrated evolutionary conflict.

2. Anaerobic FECA in a Euxinic Ocean

Two aspects of hypothetical initial interactions between the partners that comprised FECA are outlined above, one purely anaerobic, the other purely aerobic. In neither case are the sulfur compounds in a euxinic ocean considered. Of course, hydrogen sulfide mimics molecular oxygen and inhibits cytochrome oxidase (complex IV), the terminal electron carrier that reduces molecular oxygen to water. Environments in which molecular oxygen may have been intermittently available (e.g., because of photosynthetic cyanobacteria) would likely have been limited to the narrow photic zone (e.g., [11][14]). What of FECA that dispersed into the depths? The hydrogen hypothesis is attractive in this context, but some modern mitochondria exhibit other anaerobic pathways.

At least as far as has been determined, modern eukaryotes exhibit a diverse and sophisticated metabolism of sulfur compounds. Hydrogen sulfide can be formed in numerous locations in the cytoplasm and in the mitochondria from sulfur-containing amino acids (cysteine and homocysteine) and other sources [31][15]. Other reactive sulfur species (RSS) can be generated from various reactions of H2S, for instance, stepwise oxidation to thiyl radical (HS•), hydrogen persulfide (H2S2), persulfide radical (S2•−), and ultimately elemental sulfur (S2) [32][16]. Parallels to various forms of ROS are apparent, including that many “antioxidant” enzymes act on both RSS and ROS [32][16]. Modern mitochondria also exhibit a pathway for the breakdown of H2S via its oxidation to sulfate using sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (SQR), an evolutionarily ancient enzyme [16][2].

The sulfur metabolism of modern eukaryotes may well be a legacy of the conditions in the Proterozoic oceans under which eukaryotes evolved. For example, Searcy [33][17] suggests that eukaryotes may have arisen as a syntrophic relationship between sulfur-oxidizing protomitochondria and sulfur-reducing archaea (see also [11][14]). With a constellation of RSS present in eukaryotic cells [31[15][16][18],32,34], it would seem reasonable to consider their role in scavenging electrons from mitochondrial electron transport. Since a biomedical context largely frames the current focus on RSS, this nevertheless has not been done. In the aerobic cells that are the focus of biomedicine, RSS are usually considered to be electron donors rather than electron acceptors. On the other hand, sulfate-reducing bacteria play a large role in the biosphere-level sulfur cycle [35][19]. Further, certain RSS, e.g., the thiyl radical and similar molecules, are strong oxidants [34][18].

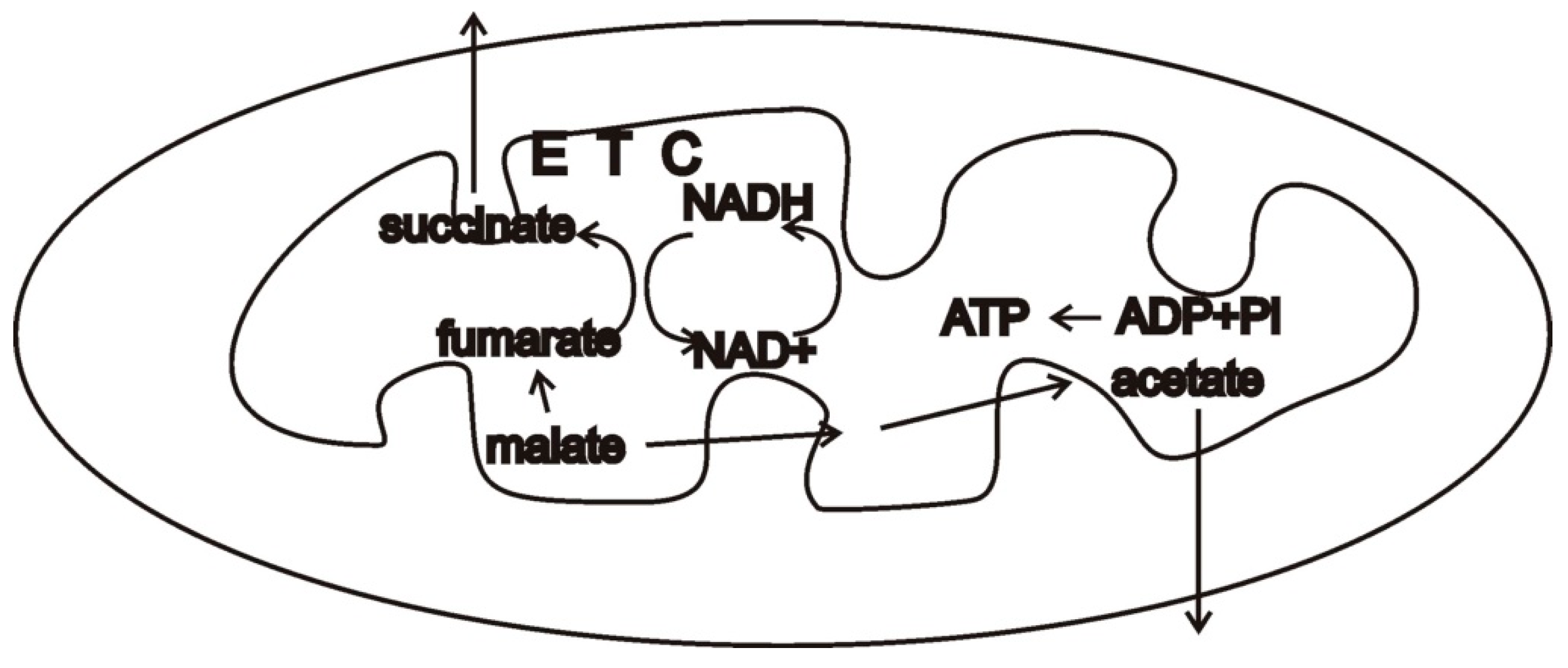

In this context, consider malate dismutation, a type of anaerobic mitochondrial metabolism that is widely found in animals [16][2]. Malate formed in the cytosol from oxaloacetate allows re-oxidizing the NADH from glycolysis. Malate is then imported into mitochondria and a portion of it is oxidized while a portion is reduced. The oxidative branch produces NADH, which must be re-oxidized, and succinate, which may be converted into acetate. The other portion of malate is converted to fumarate, then succinate by running the Krebs cycle backwards. NADH is oxidized by complex I of the electron transport chain. Rhodoquinone carries these electrons to the membrane-bound fumarate reductase which deposits them on fumarate, forming succinate. Succinate may be converted into other products such as acetate and propionate. While there are several other common mechanisms of anaerobic metabolism in eukaryotes that use portions of the electron transport chain, malate dismutation may serve as a useful example (Figure 31).

Figure 31. Simplified schemata of malate dismutation [16][2], a possible type of anaerobic metabolism of a protomitochondrion. Malate is oxidized to pyruvate and acetate, reducing NAD+ to NADH. Malate is also reduced to fumarate and succinate, and possibly other products, oxidizing NADH to NAD+ by using a portion of the electron transport chain (ETC). A syntrophic partner that could take up succinate, acetate, and other products would be valuable by diminishing end-product inhibition (Figure 42).

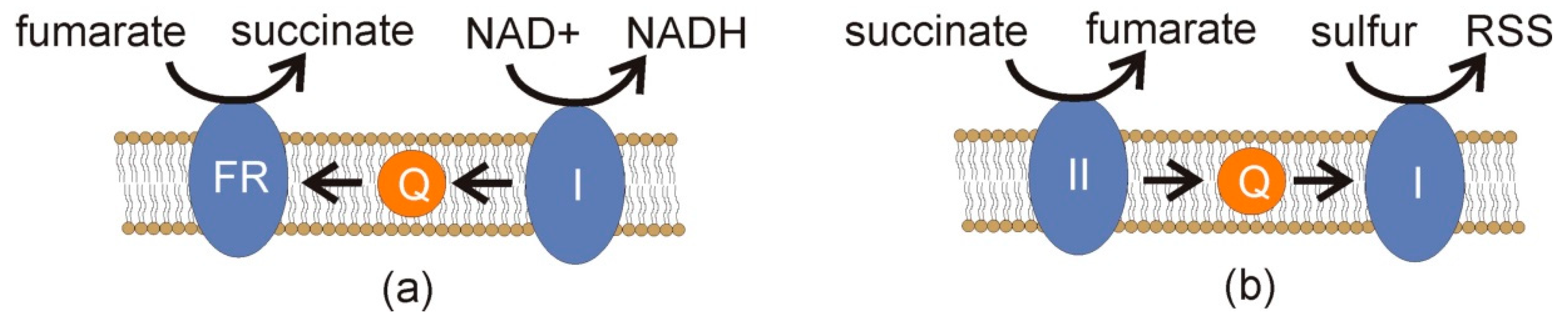

Figure 42. Simplified schemata of a scenario for RSS formation under anaerobic conditions. (a) As part of the reductive branch of malate dismutation [16][2], NADH is oxidized to NAD+ by complex I (I) of the electron transport chain (Figure 31). Electrons are carried by rhodoquinone (Q) to fumarate reductase (FR), reducing fumarate to succinate. (b) If succinate accumulates, it can inhibit the process in (a) and donate electrons to complex II (II) of the electron transport chain, resulting in reverse electron transport in which ubiquinone (Q) carries electrons to complex I (I), and these electrons are ultimately scavenged by sulfur to form RSS. Paralleling Figure 2, sSuch RSS formation would select for exporting succinate and related products to avoid this sort of end-product inhibition.

If end-product inhibition occurs, e.g., the cell has a surfeit of acetate and propionate, a build-up of succinate can occur. Such a build-up can pose risks in the presence of oxygen. When succinate donates electrons to complex II, reverse electron transfer can occur, and electrons flowing to complex I can be cast off to molecular oxygen if it is present, leading to ROS [36][20]. When oxygen is absent and hydrogen sulfide is present, reverse electron transfer would seem highly likely, since both H2S and the lack of molecular oxygen will inhibit canonical electron transfer. Under these conditions, RSS might increase to harmful levels (Figure 42). Thus, there would be strong selection to avoid end-product inhibition in the disposal of succinate, acetate, propionate, and any other products. In this way, a symbiont that took up and metabolized these molecules would be a valuable partner indeed.

References

- Collin, R.; Miglietta, M.P. Reversing opinions on Dollo’s Law. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 602–609.

- Martin, W.F.; Tielens, A.G.M.; Mentel, M. Mitochondria and Anaerobic Energy Metabolism in Eukaryotes; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- Martin, W.; Muller, M. The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote. Nature 1998, 392, 37–41.

- Chance, B.; Williams, G.R. The respiratory chain and oxidative phosphorylation. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Subj. Biochem. 1956, 17, 65–134.

- Kunji, E.R.S.; Crichton, P.G. Mitochondrial carriers function as monomers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797, 817–831.

- Bertholet, A.M.; Chouchani, E.T.; Kazak, L.; Angelin, A.; Fedorenko, A.; Long, J.Z.; Vidoni, S.; Garrity, R.; Cho, J.; Terada, N.; et al. H+ transport is an integral function of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Nature 2019, 571, 515–520.

- Blackstone, N.W. Energy and Evolutionary Conflict: The Metabolic Roots of Cooperation; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022.

- Blackstone, N.W. Why did eukaryotes evolve only once? Genetic and energetic aspects of conflict and conflict mediation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2013, 368, 20120266.

- Blackstone, N.W. The impact of mitochondrial endosymbiosis on the evolution of calcium signaling. Cell Calcium 2015, 57, 133–139.

- Jacobson, J.; Duchen, M.R. Interplay between mitochondria and cellular calcium signaling. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2004, 256/257, 209–218.

- Berridge, M.J.; Bootman, M.D.; Roderick, H.L. Calcium signaling: Dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 517–529.

- Blackstone, N.W. A units-of-evolution perspective on the endosymbiont theory of the origin of the mitochondrion. Evolution 1995, 49, 785–796.

- Blackstone, N.W. Reactive oxygen species signaling pathways: Arbiters of evolutionary conflict? Oxygen 2022, 2, 269–285.

- López-García, P.; Moreira, D. The Syntrophy hypothesis for the origin of eukaryotes revisited. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 655–667.

- Olson, K.R. Hydrogen sulfide, reactive sulfur species and coping with reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 140, 74–83.

- Olson, K.R. The biological legacy of sulfur: A roadmap to the future. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2021, 252, 110824.

- Searcy, D.G. Metabolic integration during the evolutionary origin of mitochondria. Cell Res. 2003, 13, 229–238.

- Lau, N.; Pluth, M.D. Reactive sulfur species (RSS): Persulfides, polysulfides, potential, and problems. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 49, 1–8.

- Plugge, C.M.; Zhang, W.; Scholten, J.C.M.; Stams, A.J.M. Metabolic flexibility of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 81.

- Roca, F.J.; Whitworth, L.J.; Prag, H.A.; Murphy, M.P.; Ramakrishnan, L. Tumor necrosis factor induces pathogenic mitochondrial ROS in tuberculosis through reverse electron transport. Science 2022, 376, 1431.

More