Dilophosauridae is a family of medium to large sized theropod dinosaurs. The name Dilophosauridae is derived from Greek, with “di-” meaning “two,” “lophos” meaning “crest,” “sauros” meaning “lizard,” and “-idae” meaning “family”. While the name suggests that all dilophosaurids have two crests, this is not applicable to all dilophosaurids. The Dilophosauridae is anchored by its type genus, Dilophosaurus, and therefore the name comes from the distinctive two crests of the genus.

- dilophosauridae

- dilophosaurids

- dilophosaurus

1. Description

Dilophosaurids were large bipedal predators with lengths of 4 to 7 metres and estimated adult weights of 300 to 500 kg. They are well known for their distinctive head crests, which were probably used for mating displays, or to intimidate rivals.[1]

All dilophosaurids are characterized by a hole in the premaxilla, few maxillary teeth, a slot-shaped opening at the base of the nasal process of the premaxilla, nasolacrimal crests, and a number of dorsal tab-like bumps on the articular, which is located on the back end of the lower jaw.[2]

1.1. Body Size

Dilophosaurus had an average femur length of 552 mm, body lengths of 6 to 7 meters, and body masses of 362 kg.[3] The dilophosaurid Dracovenator had a body length of approximately 5.5 to 7.0 meters long.[1]

Due to a lack of endemism of Dilophosauridae, body size has been used to weakly classify taxa to Dilophosauridae. Dilophosaurus and Dracovenator are both genera of similar body length, estimated to be around 6–7 meters in length, providing some support for these two taxa as belonging to the same family.[4]

2. Classification

The family Dilophosauridae was proposed by Alan Charig and Andrew Milner in 1990 to contain only the type genus, Dilophosaurus.[5] Other genera, such as Zupaysaurus and Dracovenator, have since been assigned to this family, though the group has never been given a phylogenetic definition and is not currently a clade. Some studies have suggested that there was a natural group of medium-sized crested theropods which included Dilophosaurus as well as Dracovenator, Cryolophosaurus, and Sinosaurus, though it has not been formally named Dilophosauridae.[6] While traditionally assigned to the superfamily Coelophysoidea, these analyses suggest that dilophosaurids may have been more closely related to the group Tetanurae, comprising the more advanced megalosaurs, carnosaurs and coelurosaurs.

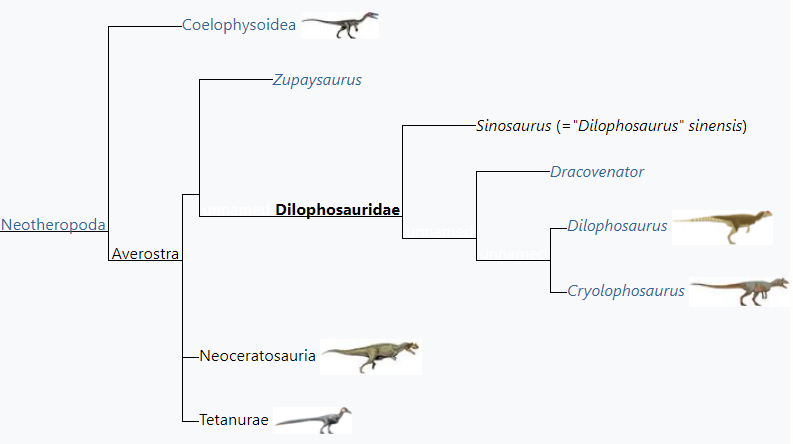

The following cladogram outlines the relationships of Dilophosaurus and its close relatives as recovered by the 2007 analysis of Smith, Makovicky, Pol, Hammer, and Currie.[6]

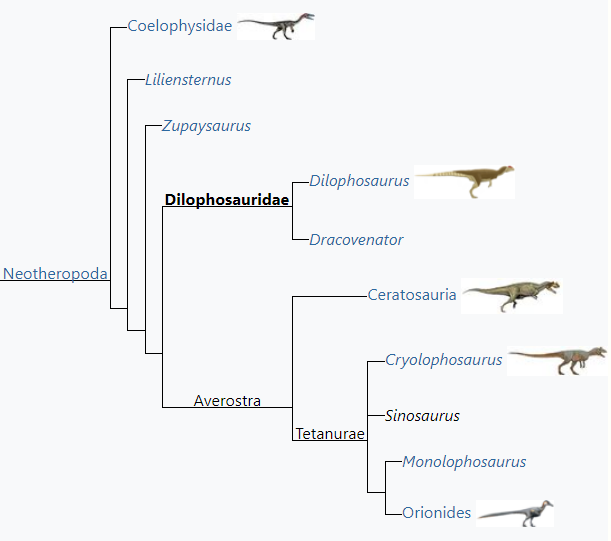

In 2015, Hendrickx et al. proposed a family tree that reflects a more restricted view of the family Dilophosauridae. Although Dilophosauridae previously included Dilophosaurus, Dracovenator, Sinosaurus, and Crylophosaurus, recent research has supported a more narrowly defined family Dilophosauridae containing only Dilophosaurus and Dracovenator and excluding Sinosaurus and Crylophosaurus.[7] This change was supported by similarities between Dracovenator, Dilophosaurus wetherilli and Zupaysaurus rougieri, suggesting these taxa might form their own clade sister to Dilophosauridae, although there is no definitive evidence.[8] Sinosaurus and Crylophosaurus are also now classified as basal tetanurans.[9] While all of the dinosaur genera once within Dilophosauridae are characterized by a distinctive cranial crest, it is thought that this distinctive trait was convergently evolved in dilophosaurids and basal tetanurans, and thus not all are necessarily derived from the same common ancestor.

The following family tree illustrates a synthesis of the relationships of the early theropod groups compiled by Hendrickx et al. in 2015, and follows more recent research showing a more restricted Dilophosauridae.[7]

3. Paleobiology

All dilophosaurids are known for large, distinctive, head crests. These crests have been thought to have had many different uses, including being used for display, to attract mates, or intimidate rivals. It has been suggested that the crests symbolized sexual dimorphism, but this interpretation of the crests is controversial. Another distinctive cranial feature is a notch between the premaxilla and maxilla, giving dilophosaurids a crocodile-like appearance. This makes some people, for example David B. Norman, suspect that their front teeth were too weak to bring down prey, and that they were scavengers. Tracks found in Utah might show that dilophosaurids could swim, implying that they fed on fish.[9]

4. Palaeoecology

While dilophosaurids flourished during the Early Jurassic, they were mostly extinct by the end of the Early Jurassic period (201.3-174.1 Ma). Dilophosaurid fossils have been found on two continents: Dilophosaurus wetherilli was discovered in North America and Dracovenator regenti[8] was discovered in South Africa. The taxa previously considered Dilophosaurids, Sinosaurus and Cryolophosaurus, have been found in China (Dong 2003; Xing et al. 2013a, 2014) and Antarctica,[4] respectively.

A lack of endemism within the family Dilophosauridae makes it difficult to pinpoint a single geographic origin for the group.[4] Dilophosaurus fossils originate from the Kayenta Formation (dates to Early Jurassic, 196–183 million years ago) of the southwest region of the United States. In addition to Dilophosaurus, ‘Syntarsus’ kayentakatae is another taxa from the Kayenta Formation, despite being distantly related to Dilophosaurus.[4] Syntarsus similarly occurred in the Upper Elliot Formation of South Africa, where both Dracovenator and Coelophysis rhodesiensis have been found in a similar region despite not being closely related to one another.[4]

During the Early Jurassic, many unrelated basal theropods existed in similar geographic regions, as exemplified through the Kayenta Formation and the Upper Elliot Formation.[4] A hypothesis proposed by Smith et al. (2007) was that there may have been resource partitioning within different geographic regions of the Early Jurassic based on differences in body size. This hypothesis, with more evidence, would help explain the lack of endemism observed in the fossil record of the Early Jurassic basal theropods.

References

- Holtz, Tom. "Dilophosaurs". Palaeos. http://palaeos.com/vertebrates/theropoda/neotheropoda2.html#Dilophosaurus.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- Wang, G. F., You, H. L., Pan, S. G., & Wang, T. (2017). A new crested theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Yunnan Province, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 55(2), 177-186.

- Smith, N.D., Makovicky, P.J., Pol, D., Hammer, W.R., and Currie, P.J. (2007). "The Dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic Review and Synthesis". U.S. Geological Survey and The National Academies doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp003 https://doi.org/10.3133%2Fof2007-1047

- Charig, A.J. and Milner, A.C. (1990). "The systematic position of Baryonyx walkeri, in the light of Gauthier's reclassification of the Theropoda." In Carpenter, K. and Currie, P.J. (eds.), Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches, Cambridge University Press: 127-140.null

- Smith, N.D., Makovicky, P.J., Pol, D., Hammer, W.R., and Currie, P.J. (2007). "The dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic review and synthesis." In Cooper, A.K. and Raymond, C.R. et al. (eds.), Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World––Online Proceedings of the 10th ISAES, USGS Open-File Report 2007-1047, Short Research Paper 003, 5 p.; doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp003. https://doi.org/10.3133%2Fof2007-1047.srp003

- Hendrickx, C., Hartman, S.A., & Mateus, O. (2015). An Overview of Non- Avian Theropod Discoveries and Classification. PalArch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology, 12(1): 1-73.

- Yates, A. M. (2005) A new theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and its implications for the early evolution of theropods.

- Xing, L.D. (2012). "Sinosaurus from Southwestern China". Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta (Edmonton): 1–286. http://hdl.handle.net/10402/era.28454.