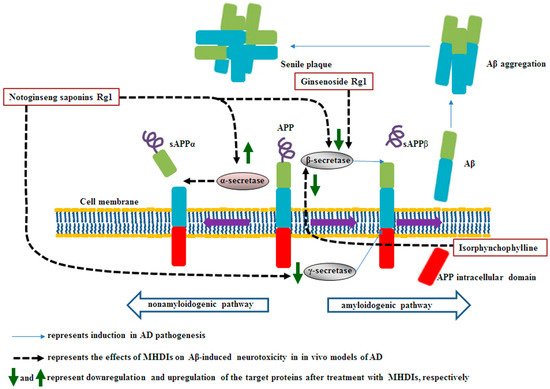

Under physiological conditions, the transmembrane glycoprotein amyloid precursor protein (APP) plays a major role in central nervous system maturation and cell contact and adhesion. However, APP overexpression can cause the production of neurotoxic derivatives, closely related to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) development [32,33]. APP can be cleaved by α-secretase to initiate the nonamyloidogenic cascade preventing Aβ accumulation. Aβ peptides are produced from APP cleavage through the activation of β- and γ-secretases in the brain regions, particularly in the temporal and frontal lobes during the early AD stages.

1. Medicinal Herbs and their Derived Ingredients (MHDIs)-Mediated Suppression of Aβ Accumulation

1.1. Effects of (Medicinal Herbs and Their Derived Tngredients) MHDIs on Aβ Accumulation through α-, β-, and γ-Secretase Activity Regulation

Notoginseng saponin Rg1, derived from

Panax notoginseng, ameliorates cognitive deficits partly by downregulating β- and γ-secretase expression in the hippocampus at 28 days after Aβ

1–42-induced A

lzheimer’s disease (AD

) [1][35]. In 2021, Guo et al. also reported that ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates Aβ accumulation partly by inhibiting β-secretase in the hippocampus after 6 treatment weeks in Aβ

25–35-induced AD

[2][38]. Furthermore, γ-secretase is a transmembrane protein complex containing four subunits (e.g., presenilin 1), and the activity of β-site

amyloid precursor protein (APP

)-cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE-1), a β-secretase, is the rate-limiting factor for Aβ accumulation, which causes hippocampal neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction

[1][3][4][17,35,39]. Therefore, BACE-1 may be a biomarker and therapeutic target for AD

[2][38]. Previous studies have demonstrated that increased BACE-1 might accelerate AD pathogenesis, and pharmacological inhibition of BACE-1 reduces Aβ deposition in the brain during AD treatment

[5][6][40,41]. Isorphynchophylline, extracted from

Uncaria tomentosa, reduces Aβ generation and deposition partly through a decrease in BACE-1 expression in the brain at 129 days in TgCRND8 transgenic mice

[7][42]. However, strong inhibition of BACE-1 causes serious adverse effects including sensorimotor gating deficits and schizophrenia, indicating that the balance of BACE-1-mediated signaling appears to be important in AD

[5][40]. Now, researchers consider the possibility that a moderate decrease in BACE-1 activity would provide benefits and avoid adverse effects for AD prevention and treatment

[5][8][40,43].

1.2. Summary

MHDIs mentioned in this section inhibit Aβ accumulation by upregulating α-secretase activities and downregulating β- and γ-secretase activities in the hippocampus in the late phase of AD in animal models (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the effects of MHDIs on Aβ accumulation in the hippocampus in the late phase of AD in in vivo models. sAPP, soluble amyloid precursor protein.

Table 1.

MHDIs that suppress Aβ accumulation in AD animal models.

Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; MAP-2, microtubule-associated protein 2; NeuN, neuronal nuclei, Bax, Bcl-2-associated x protein.

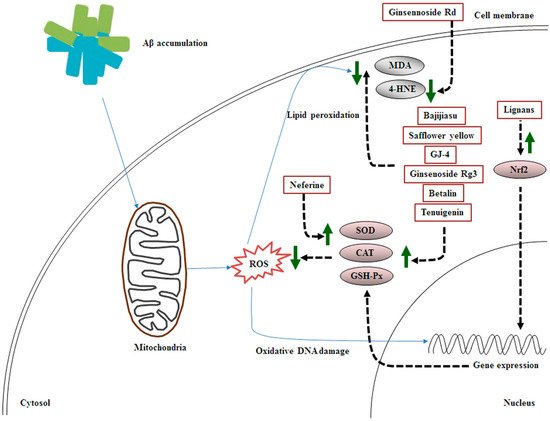

2. MHDI-Mediated Inhibition of Aβ-Induced Oxidative Stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced oxidative stress elicited in the early stages of AD is closely associated with Aβ generation, which leads to synaptic dysfunction and cognitive impairment

[9][10][22,44]. Superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, and hydrogen peroxide are crucial ROS types, which attack intracellular DNA, proteins, and lipids. In addition, mitochondria are considered the main cellular source for the production of free radicals (e.g., superoxide anions)

[11][45].

2.1. Involvement of Decreased Antioxidant Status and Increased Lipid Peroxidation in Aβ-Induced Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between increased free radicals and decreased antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px). SOD catalyzes the conversion of superoxide anions to hydrogen peroxide

[12][18]. CAT attenuates oxidative stress by converting cellular hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen and CAT deficiency is closely related to AD pathogenesis

[13][46]. GSH-Px can cause hydrogen peroxide clearance and diminish hydroxyl radical generation

[12][14][18,47]. After Aβ accumulation, excessive ROS attack cellular organelles under impaired antioxidant defense, causing a considerable decrease in SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px levels and the exacerbation of AD progression

[12][15][18,48]. ROS attack the neuronal cell membrane and then lead to neuronal cell damage through lipid peroxidation, which causes the formation of reactive aldehydes, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA), resulting in increased membrane permeability and decreased membrane activity

[4][12][18,39]. Moreover, MDA, a toxic lipid peroxidation byproduct, disrupts protein synthesis, eventually leading to cognitive impairment

[16][49].

2.2. Effects of MHDIs on Aβ-Induced Oxidative Stress through Antioxidant Activity and Lipid Oxidation Regulation

Ginsennoside Rd, derived from

Panax ginseng, ameliorates memory and learning deficits partly by downregulating 4-HNE expression in the hippocampus at 5 days after Aβ

1–40-induced AD

[17][50]. Nuclear-related factor-2 (Nrf2), a pivotal transcription factor, translocates to the nucleus, binds to the antioxidant response element, produces antioxidant factors, and regulates the defense system to protect against oxidative stress

[18][51]. Kynurenic acid can activate Nrf2-mediated signaling to reduce oxidative stress-induced neuronal damage

[19][52]. Lignans, isolated from

Schisandra chinensis Baill, protect against Aβ-induced oxidative stress by promoting kynurenic acid–induced Nrf2-mediated signaling in the brain at 28 days after Aβ

25–35-induced AD

[20][53]. GSH-Px, a major endogenous antioxidant, is key to ROS detoxification and cellular redox homeostasis maintenance. Thus, disruption of GSH-Px homeostasis in the brain is closely related to AD development

[21][31]. However, elevated expression of GSH-Px has been noted in the brains of patients with mild cognitive deficits

[22][54]. In 2014, Chen et al. found that bajijiasu, isolated from

Morinda officinalis, alleviates Aβ-induced oxidative stress mainly through SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px activity upregulation and MDA activity downregulation in the hippocampus at 25 days after Aβ

25–35-induced AD

[23]. Safflower yellow, isolated from

Carthamus tinctorius, reduces Aβ-induced oxidative stress partly by upregulating SOD and GSH-Px activities and downregulating MDA activity in the hippocampus at 28 days after Aβ

1–42-induced AD

[24][55]. In 2018, Zang et al. demonstrated that GJ-4, extracted from

Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis, alleviates memory deficit partly via increased SOD and decreased MDA levels in the cortex and hippocampus at 10 days after Aβ

25–35-induced AD

[25][56]. Tenuigenin, derived from

Polygala tenuifolia Willd., effectively ameliorates memory deficit and oxidative stress mainly through increased SOD and GSH-Px activities and decreased MDA and 4-HNE activities in the hippocampus at 28 days after streptozotocin (STZ)-induced AD

[14][47]. In 2019, Zhang et al. reported that ginsenoside Rg3, isolated from

P. ginseng C. A. Meyer, prevents cognitive dysfunction partly by enhancing SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px expression and reducing MDA expression in the hippocampus at 60 days after D-galactose-induced AD

[26][57]. In 2020, Yin et al. reported that neferine, isolated from

Nelumbo nucifera, protects against cognitive deficits partly by restoring SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px activities in the hippocampus at 4 days after aluminum chloride (AlCl

3)-induced AD

[27][58]. However,

Rhodiola crenulata extract was noted to alleviate oxidative stress by downregulating GSH-Px expression in the hippocampus at 28 days after Aβ

1–42-induced AD

[21][31]. In 2021, Shunan et al. demonstrated that betalin, from

Beta vulgaris L., significantly attenuates cognitive deficits partly by upregulating SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px expression and downregulating MDA expression in the hippocampus at 28 days after AlCl

3-induced AD

[15][48].

2.3. Summary

Taken together, the MHDIs mentioned in this section inhibit Aβ-induced oxidative stress mainly by enhancing the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px and reducing the levels of lipid peroxidation products such as 4-HNE and MDA in the cortex and hippocampus in the early and late phases of AD in animal models (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the effects of MHDIs on Aβ-induced oxidative stress in the cortex and hippocampus in the early and late phases of AD in in vivo models.

Table 2.

MHDIs that inhibit Aβ-induced oxidative stress in AD animal models.

| Major Ingredients |

Isolated from Medicinal Herbs |

Antioxidative Stress Activities |

Models |

References |

| Ginsennoside Rd |

Panax ginseng |

4-HNE↓ |

5 days after Aβ1–40-induced AD |

[17][50] |

| Lignans |

Schisandra chinensis Baill |

kynurenic acid↑, Nrf2↑ |

28 days after Aβ25–35-induced AD |

[20][53] |

| Bajijiasu |

Morinda officinalis |

SOD↑, CAT↑, GSH-Px↑, MDA↓ |

25 days after Aβ25–35-induced AD |

[23] |

| Safflower yellow |

Carthamus tinctorius |

SOD↑, GSH-Px↑, MDA↓ |

28 days after Aβ1–42-induced AD |

[24][55] |

| GJ-4 |

Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis |

SOD↑, MDA↓, iNOS↓, COX-2↓, PGE2↓, TNF-α↓ |

10 days after Aβ25–35-induced AD |

[25][56] |

| Tenuigenin |

Polygala tenuifolia Willd |

SOD↑, GSH-Px↑, MDA↓, 4-HNE↓

p-tau (Ser396) ↓, p-tau (Thr181) ↓ |

28 days after STZ-induced AD |

[14][47] |

| Ginsenoside Rg3 |

P. ginseng C. A. Meyer |

SOD↑, CAT↑, GSH-Px↑, MDA↓, |

60 days after D-galactose-induced AD |

[26][57] |

| Neferine |

Nelumbo nucifera |

SOD↑, CAT↑, GSH-Px↑ |

4 days after AlCl3-induced AD |

[27][58] |

| |

Rhodiola crenulata |

GSH-Px↓, arachidonic acid↓ |

28 days after Aβ1–42-induced AD |

[21][31] |

| Betalin |

Beta vulgaris L. |

SOD↑, CAT↑, GSH-Px↑, MDA↓, |

28 days after AlCl3-induced AD |

[15][48] |

iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.