Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Amina Yu and Version 1 by Duygu AĞAGÜNDÜZ.

Fermentation is one of the oldest biological food preservation methods, mainly known for enhancing the organoleptic properties of foods in the desired direction and extending food shelf life. The nutritional value of the food increases as essential amino acids, vitamins, and antimicrobial metabolites such as bacteriocin are synthesized during fermentation, which also breaks down fermentable carbohydrates into organic acids, carbon dioxide, and alcohol. These antimicrobial metabolites contribute to food safety by preventing the spoilage of foods by microorganisms. Moreover, fermentation reduces antinutritional factors, increases the digestibility of foods, and ultimately improves the sensory properties of foods.

- novel microorganisms

- fermentation

- function

- safety

- health

1. Clostridium butyricum

In 2014, the European Commission approved the use of Clostridium butyricum (C. butyricum) CBM 588 as a novel food ingredient, and then some companies in the UK focused on its use in food supplements [29][1]. Although its use is mostly related to its positive effects on lipid metabolism and gastrointestinal microbiome modulation, this bacterium has many promising potentials in industry, environment, and health [30,31][2][3].

C. butyricum is an important microorganism because of its hydrogen productivity. It has been revealed that different organic nutrient media such as glucose, starch, animal fertilizer, agricultural wastes, food residual, and wastewater can be used as substrates in the fermentation operation. Food residual is considered a large part of its waste, which includes extra carbohydrate ingredients and can be noted as a possible raw material for biohydrogen processing [32,33][4][5]. Clostridia teams are spore-forming anaerobic bacteria and Enterobacter spp. (1 mol H2/mol hexose) with a higher yield compared to different fermentative anaerobic bacteria teams such as (2 mol H2/mol glucose) H2 can use glucose for their production. Among the fermentative hydrogen-producing bacteria, C. butyricum has been reported to be one of the high hydrogen-producing microorganisms [34][6]. In addition to this, C. butyricum has a broad spectrum of substrate usage efficiency and has been extensively investigated for hydrogen production from various substrates, including used organic waste. It is stated that it plays a role in protecting the environment and reducing waste [35][7].

C. butyricum is advantageous in food fermentation because it requires mild conditions and is anaerobic and independent of B12 Although most bacteria do not have a high tolerance for food because of several components that impede microbial growth, C. butyricum does not require food pretreatment, such as melting material, electrodialysis, effective carbon suction, and ion barter [36][8]. C. butyricum NCIMB 8082, C. butyricum JKT37, C. butyricum CWBI1009, and C. butyricum L4 are the strains that play a role in food fermentation [37,38,39,40][9][10][11][12].

The environmental effects of population increase and expanding economic activity highlight the need to switch from linear business models to resources wise and sustainable business models [33][5]. Using waste as a source of raw materials in industry to minimize negative environmental effects and process costs is one of the key tenets of the circular economy [41][13]. In this investigation, Liberato et al. (2021) suggest using crude glycerol and corn soaking liquid as the raw materials for the C. butyricum NCIMB 8082 strain to produce 1,3-propanediol, an essential chemical mostly employed in the creation of polymers. After 24 h of fermentation in 65 mL serum, C. butyricum NCIMB 8082 could thrive in a culture medium containing only crude glycerol and corn-soaking broth, producing 0.51 g.g−1 and 6.56 gL−1 of 1,3-propanediol [37][9].

Many microorganisms such as Citrobacter, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Clostridium species may convert glycerol to 1,3-propanediol [42,43][14][15]. Among these, C. butyricum has received the most attention due to its high production, substrate tolerance, and prolificacy [33][5]. Additionally, C. butyricum produces 1,3-propanediol independently of B12, which typically necessitates a simpler and cheaper growth medium. Acetic acid, butyric acid, propionic acid, H2, and butanol are among the other metabolic byproducts of the C. butyricum glycerol fermentation [44][16].

2. Bacteroides xylanisolvens

In Chassard et al. (2008), Bacteroides xylanisolvens was first isolated and described from human feces. According to the analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence, the isolates belonged to the genus Bacteroides and were linked to one another closely (99.0% sequence similarity) [55][17]. Some Bacteroides species perform advantageous metabolic processes that entail the fermentation of carbohydrates, the use of nitrogenous materials, and the biotransformation of bile acids and other steroids, among other benefits for human health [56][18]. Keeping intestinal pathogens from populating the intestines concurrently short-chain fatty acids, which could have satiety-inducing, anticancer, and cholesterol-lowering qualities [57][19], the host’s immune system, and its capacity to combat viruses and disorders are preserved thanks to immunomodulatory actions that are involved in their development [58][20].

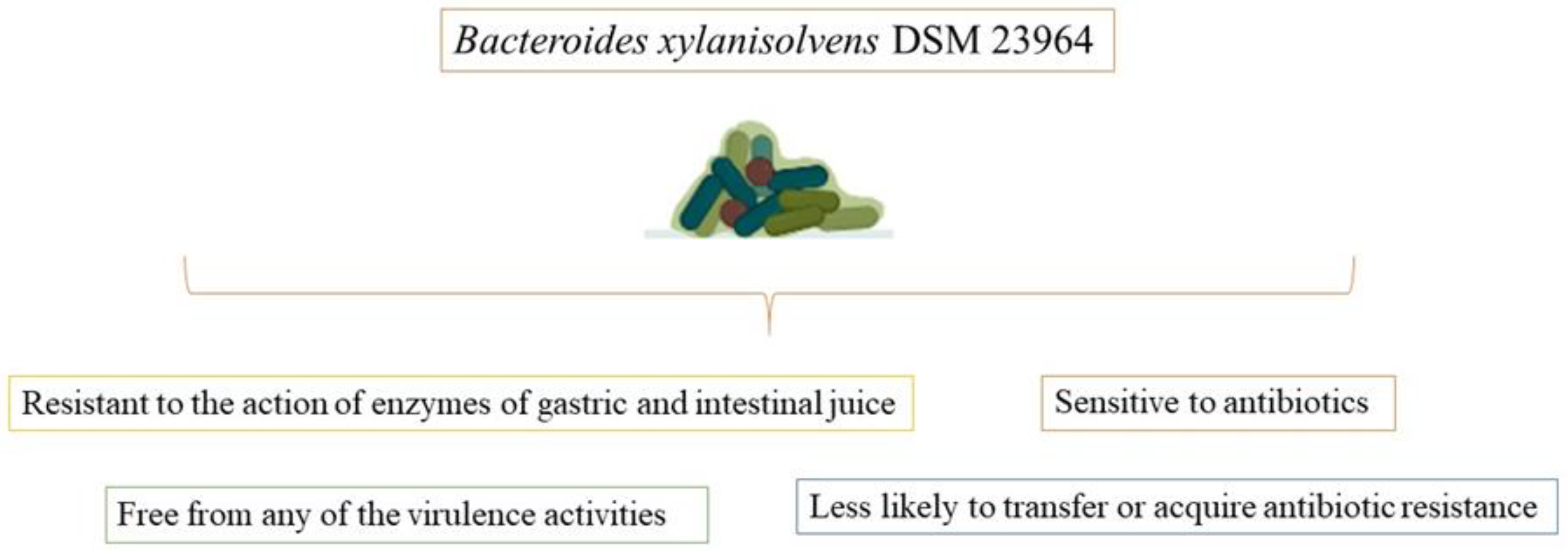

Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 is a novel species of nonpathogenic Bacteroides xylanisolvens that was discovered in the feces of healthy human individuals. Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 strain is free of any virulence factors and is sensitive to antibiotics. It is resistant to the action of the stomach and intestinal juice enzymes during nutrient fermentation (Figure 2). However, additional in vitro and in vivo tests are still required for a thorough safety analysis [59][21].

Figure 2.

Potential promising advantages of

Bacteroides xylanisolvens

DSM 23964 strain in food fermentation.

The host is sensitive to the defense system, according to the DSM 23,964 strain of Bacteroides xylanisolvens, which does not have any virulence factors, carry any mutagenic activity, exhibit any toxicological effects in live or pasteurized form, or exhibit any pathogenic properties in vivo at concentrations up to 3.3 × 1012 pasteurized bacteria/kg body weight. This demonstrates that Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964, in both live and pasteurized forms, is safe for use in food [60][22].

An anaerobic, spore-free, nonmotile, Gram-negative bacteria, Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 strain does not move short-rod or rod-shaped cells, which are typically 0.4 to 0.5 m broad and 1 to 2 m long. Wilkins-Chalgren agar colonies have a convex surface, are milky, round, elevated, and 2 to 3 mm in diameter [59][21].

Simulated gastric and intestinal secretions were used to subject the bacteria in the digestive tract to their effects. More than 90.0% of the Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 strain survived in gastric juice after 180 min, and more than 96% after 240 min of exposure to intestinal juice [59][21]. The fermentation and breakdown of xylan and other plant fibers are significantly aided by the bacteria Bacteroides xylanisolvens [55][17]. In the human diet, polysaccharides play a significant role in sustaining intestinal commensals such as Bacteroides xylanisolvens. They are capable of being converted into short- and branched-chain fatty acids, which are reabsorbed from the large intestine and supply a sizable number of the host’s daily energy requirements [61][23]. According to data, Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 is a candidate for probiotics and does not have any virulence characteristics that could impede its usage for future safety and health-promoting evaluation [59][21].

As a novel food under the Novel Food Regulation No. 258/97, pasteurized dairy products fermented with Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 received The European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) approval in 2015. It is prohibited to use this particular strain as a starter culture in the fermentation of pasteurized dairy products. However, only Bacteroides xylanisolvens inactivated cells that have been heat-inactivated were permitted in the final products. Moreover, the EFSA Panel accepted that the procedures followed were industry standards for the dairy sector, that they were sufficiently specified, and that there were no safety issues [62][24].

Anaerobic bacteria are the predominant forms in the human gut. The ability of a bacterial strain to survive through the digestive system and ultimately provide advantageous effects for the host is a crucial component of its ability to perform nutrient fermentation. Promisingly, after three hours in simulated gastric juice, Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964 showed a 90.0% survival rate, and after four hours in simulated intestinal juice, it had a 96.0% survival rate [59][21]. By lowering cholesterol levels, inducing satiety, and even having an anticarcinogenic impact, Bacteroides xylanisolvens’ synthesis of short-chain fatty acids and the fermentation of dietary polysaccharides are linked to benefits for human health [57][19].

3. Akkermansia municiphila

Akkermansia genus member Akkermansia municiphila is a microorganism that has recently come to the fore with possible health effects and currently has no history of commercial use in the food industry [29][1]. However, some experimental data on the production of innovative foods have begun to report promising results on the use of this bacteria, especially in terms of fermentation and probiotic-potential-mediated health effects.

Derrien, Vaughan, Plugge, and De Vos (2004) discovered Akkermansia muciniphila, a novel genus of the phylum Verrucomicrobia and a member of the commensal gut microbiota. The ATCC BAA-835-type strain of Akkermansia muciniphila is the most researched variety [63][25]. The Akkermansia muciniphila genome stands apart from other Verrucomicrobia genomes because 28.8% of its genes are shared with the organism’s closest relatives [64][26]. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and quantitative PCR (qPCR), it was discovered that Akkermansia muciniphila accounted for more than 1.0% of the entire microbiota (3.0–5.0% of the gut microbiota in healthy individuals) [65,66][27][28]. Akkermansia muciniphila generally colonizes the intestinal mucus layer, intestinal colonization is complete at an early age and reaches the level observed in adults within a year. Akkermansia muciniphila colonization decreases with increasing age [67][29]. Akkermansia muciniphila is nonmotile, non-spore-forming, oval-shaped, chemo-organotrophic, and it requires mucin as a carbon source along with nitrogen and enzymes that break down mucin [29][1].

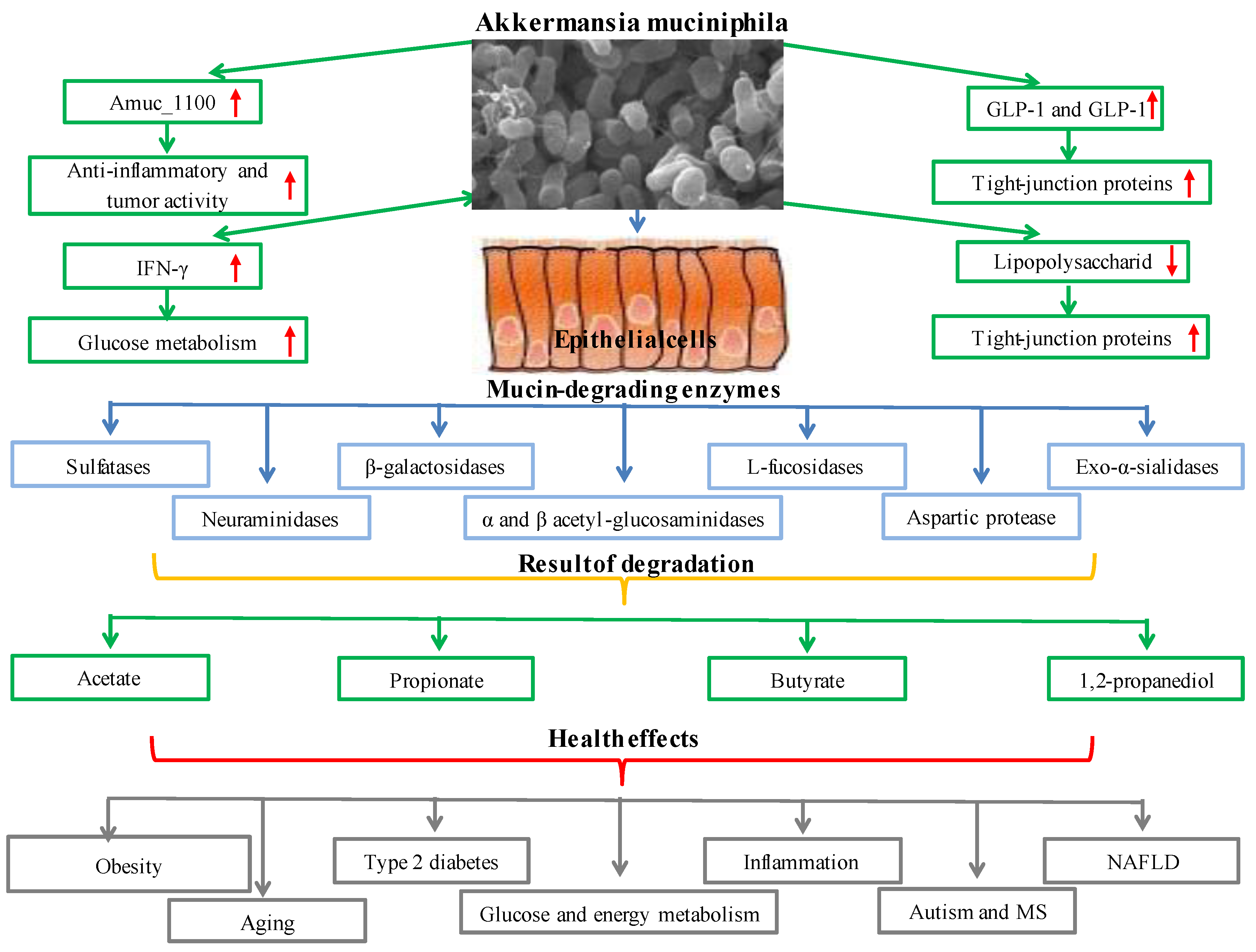

The primary component of mucus, mucin, is a collection of glycoproteins found in mucus discharges. The oligosaccharides N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (GalNAc), N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc), D-galactose L-fucose, and other amino and monosaccharide sugars are glycosylated to produce the mucus layer. The selective permeability provided by this layer enables the movement of nutrients into epithelial cells. The mucus layer offers a surface layer for bacteria to grow and penetrate and is the first line of defense against mechanical harm, pathogens, and toxins [68][30]. Sulfatases, β-galactosidases, exo-α-sialidases, α and β acetyl-glucosaminidases, neuraminidases, L-fucosidase, and aspartic protease are some of the mucin-degrading enzymes found in Akkermansia muciniphila. By decomposing mucin with these enzymes, Akkermansia muciniphila generates carbon, nitrogen, and energy sources for the organism or other gut microbiota inhabitants [69,70,71,72,73][31][32][33][34][35]. Akkermansia muciniphila also degrades mucin and generates short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate, butyrate, and 1,2-propanediol (which is then metabolized to propionate). Additionally, the inflammatory toxicity of sulfate in the mucin layer might be reduced by Akkermansia muciniphila employing hydrogen sulfide for cysteine synthesis [74][36]. By binding to and subsequently activating the signaling pathway to control glucose and lipid metabolism in the peripheral organs, butyrate Gpr41 or Gpr43 are generated by Akkermansia muciniphila [66][28]. Fucose, galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, sialic acid, disaccharide, and tiny oligosaccharides are also released because of mucin degradation. Mucin degradation provides the energy needs of the microbiota and gives an advantage for starvation, malnutrition, and total parenteral nutrition [75][37]. Akkermansia muciniphila increases the activity of L cells and stimulates the release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) from L cells. The organism Akkermansia muciniphila enhances the release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) from L cells and boosts the activity of L cells. In addition to increasing the number of goblet cells and the expression of tight-junction proteins such as zonulin (ZO-1), ZO-2, and ZO-3, Akkermansia muciniphila restores the host’s mucus layer thickness to normal [76][38]. By inhibiting the transfer of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from the colon to the blood, Akkermansia muciniphila lowers endotoxemia and improves intestinal permeability [77][39]. The Akkermansia muciniphila outer membrane protein, Amuc_1100, is essential for contact with the host. The anti-inflammatory and antitumorigenic properties of the Amuc 1100 protein, the restoration of tryptophan levels, and the stimulation of serotonin metabolism all impact the health of the host [78][40]. Additionally, the toll-like receptors (TLR2) signaling pathway allows the particular cytokine IL-10 to be produced when the Akkermansia muciniphila outer membrane protein Amuc 1100 is present [79][41].

Systemic glucose metabolism is impacted by IFN-γ a key immune system cytokine [80][42]. IFN-γ regulates the production of genes such as the immune-associated GTPase family (Irgm1), guanylate-binding protein 4 (Gbp4), and ubiquitin D(Ubd), which helps control the amount of Akkermansia muciniphila in the gut. Akkermansia muciniphila mediates the impact of IFN-γ on glucose tolerance through this pathway [81,82][43][44]. The effects of Akkermansia muciniphila include reducing metabolic inflammation, enhancing intestinal integrity, boosting intestinal peptide hormone secretion, and improving metabolic parameters. Because of these effects, Akkermansia muciniphila is one of the most promising biotherapeutic agents for metabolic diseases, including obesity ([83][45], type 2 diabetes [84][46], inflammation, glucose and energy metabolism [85][47], nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [86][48], aging, autism, and multiple sclerosis [87,88,89][49][50][51]. It has been determined time and time again that Akkermansia muciniphila is a crucial part of the gut microbiota [90,91,92][52][53][54]. The functional and metabolic functions and health effects of Akkermansia muciniphila are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Metabolic functions and health effects of

Akkermansia muciniphila

.

4. Mycobacterium setense manresensis

Mycobacterium setense manresensis is a microorganism that has stood out recently, especially in terms of novel food production; it is an encapsulated ingredient composed of ≤105 heat-killed, freeze-dried Mycobacterium setense manresensis [93][55]. Recently, some opinions have begun to be put forward regarding the use of this microorganism in fermentation and probiotic production although there is limited information in the literature.

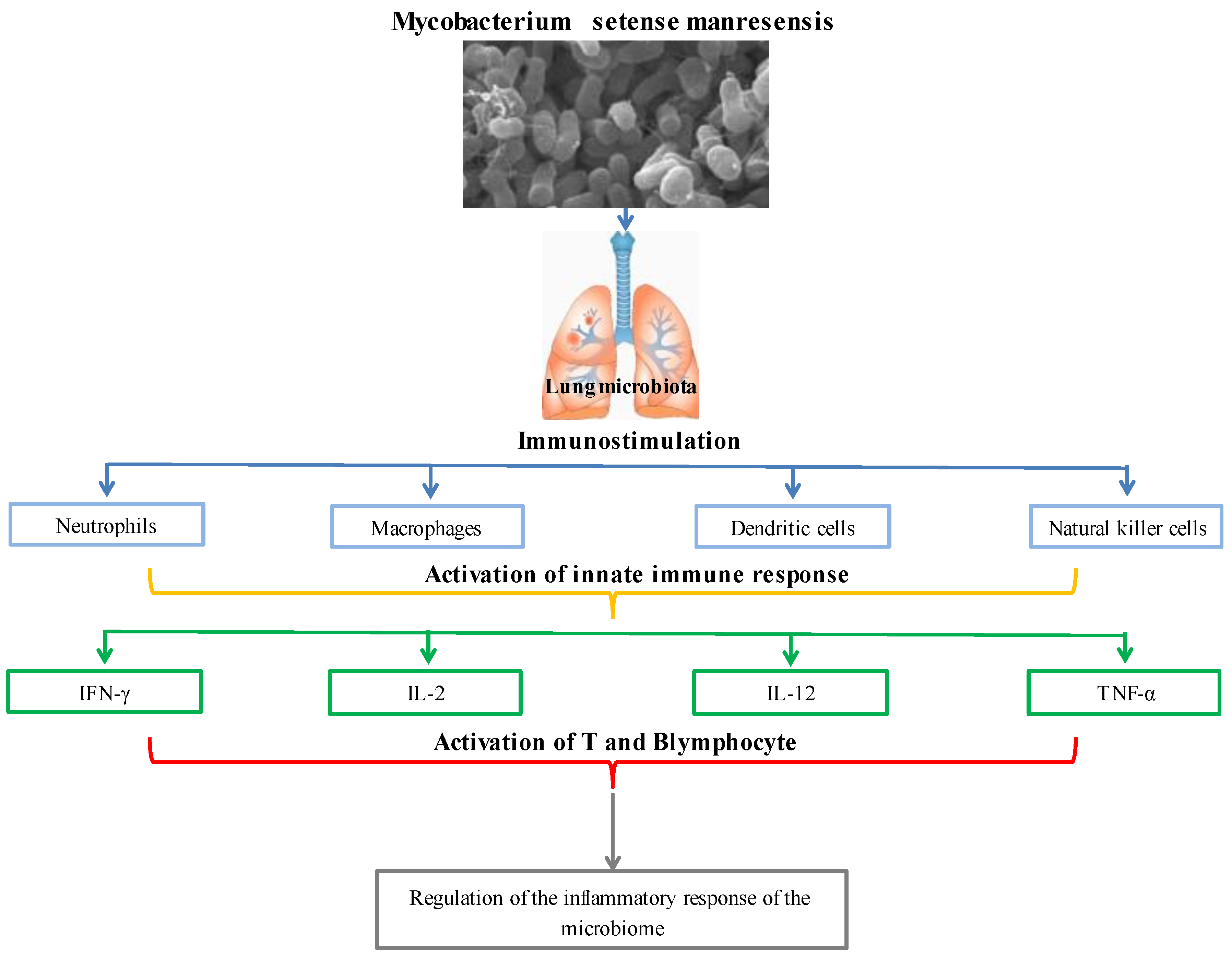

Quickly proliferating and commonly recognized nontuberculous nonpathogenic mycobacteria (NTM) species known as Mycobacterium fortuitum cause localized skin and soft tissue infections. Numerous strains of the Mycobacterium fortuitum complex are also known as Mycobacterium peregrinums, Mycobacterium porcinum, Mycobacterium septicum, Mycobacterium conceptionense, Mycobacterium boenickei, Mycobacterium houstonense, Mycobacterium neworleansense, Mycobacterium brisbanense, Mycobacterium farcinogenes, and Mycobacterium senegalense [94,95][56][57]. With their adaptable ecological and symbiotic biological characteristics, nontuberculous nonpathogenic mycobacteria may thrive in various habitats, from harsh natural surroundings to microniches in the human body [96][58]. Nontuberculous and nonpathogenic mycobacteria stimulate the local lung microbiota, neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic, and natural killer (NK) cells to activate the innate immune system. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nod-like receptors in the activated innate immune system allow for the identification of mycobacterial and microbial pathogen-associated molecular models (PAMPs) (NLRs). Recognized PAMPs control the microbiome’s inflammatory response by activating T and B cells, primarily through interactions with interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-2, IL-12, and TNF-α [97][59]. TRAF6, an essential signaling molecule in TLR-triggered inflammation, is deubiquitinated by the anti-inflammatory protein A20 because of Mycobacterium fortuitum induction. By increasing TNFAIP3, which blocks TNF-induced signaling, and by blocking both MyD88-dependent and -independent TLR-induced NF-Kβ pathways, the A20 enzyme lowers inflammation. It has been claimed that Mycobacterium fortuitum A20 expression controls the host’s proinflammatory responses negatively [98][60]. Mycobacterium setense, a brand-new species that is a member of the Mycobacterium fortuitum complex, was discovered in France in a patient who was 52 years old and had soft tissue infection and osteitis. The nonpathogenic group of nontuberculous mycobacteria includes it [99,100][61][62]. This novel strain was given the name Mycobacterium setense manresensis and shares characteristics with Mycobacterium setense and other genes frequently used to identify Mycobacterium species, including AsrpoB, rpoC, hsp65, and sodA. In Catalonia, Spain, a nonpathogenic strain of Mycobacterium setense manresensis was found on a riverbank. The 6.06 Mb Mycobacterium setense manresensis genome had 22 contigs with an average coverage depth of 788. A similar Mycobacterium species GC content was found in the Manresensis strain (66.5%) [101][63]. Drinking water contained a new species of Mycobacterium setense manresensis, a member of the Mycobacterium fortuitum complex (which also includes nontuberculous bacilli responsible for skin, lymph nodes, and joint infections) [102][64]. Probiotics promote mucosal response and barrier and epithelium repair activities with the SCFAs they produce. They also stimulate IgA to raise IL-10 levels and induce CD4+ Foxp3+ T-reg by blocking the generation of proinflammatory cytokines. It can interact with mucosal epithelium and the resident cells of innate and adaptive immunity, modulating the host’s local and systemic mucosal immune response [102][64]. Additionally, it controls the immune response’s regulatory mechanisms by activating TLR2 and TLR4, enhancing NK cell activity and IFN-γ production by producing IL-12, and deactivating T-regs with the anti-inflammatory cytokine Th17 [103,104][65][66]. The immune system regulation of Mycobacterium setense manresensis is presented in Figure 4. Mycobacterium setense manresensis, a novel species from the fortuitum group discovered in drinking water, was given orally for two weeks during a typical tuberculosis treatment. This treatment both eradicated the bacilli and had an excessive impact on the patient’s condition. It was highlighted that it promoted a balanced immune response that placed a strong emphasis on managing the inflammatory response [105][67]. Total adenosine deaminase, haptoglobin, local pulmonary chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligands-1 and 5, TNF-a, IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-10 are all decreased by taking Mycobacterium setense manresensis orally [106][68]. Mycobacterium manresensis is present in Nyaditum resale®, one of the probiotics which is a galenic preparation of heat-killed Mycobacterium manresensis (hkMn). Preclinical investigations using the strain C3HeB/FeJ of murine active tuberculosis have demonstrated that daily treatment of NR containing 103–106 hkMn for 14 days can halt the development of active tuberculosis. After 7 days of ex vivo treatment of splenocytes with tuberculin-purified protein derivative (PPD) memory-specific Tregs (CD39+ CD25+ CD4+ cells), the administration of low-dose Nyaditum resale® was linked to an increase in these cells. The development of tuberculosis was inhibited by this increase in Tregs, which was also accompanied by an increase in IL-10 in the spleen and a decrease in IL-17 in the lungs [107][69]. As a result, the lesions’ development and neutrophilic infiltration were paused, which was expected to provide the lesions enough time to encapsulate [108][70]. In human randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials, Nyaditum resale® significantly increased the number of memory regulatory T cells with specificity for PPD [107][69].

Figure 4.

Immune system regulation of

Mycobacterium setense manresensis

.

5. Novel Lactic Acid Bacteria (Fructophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria (FLAB))

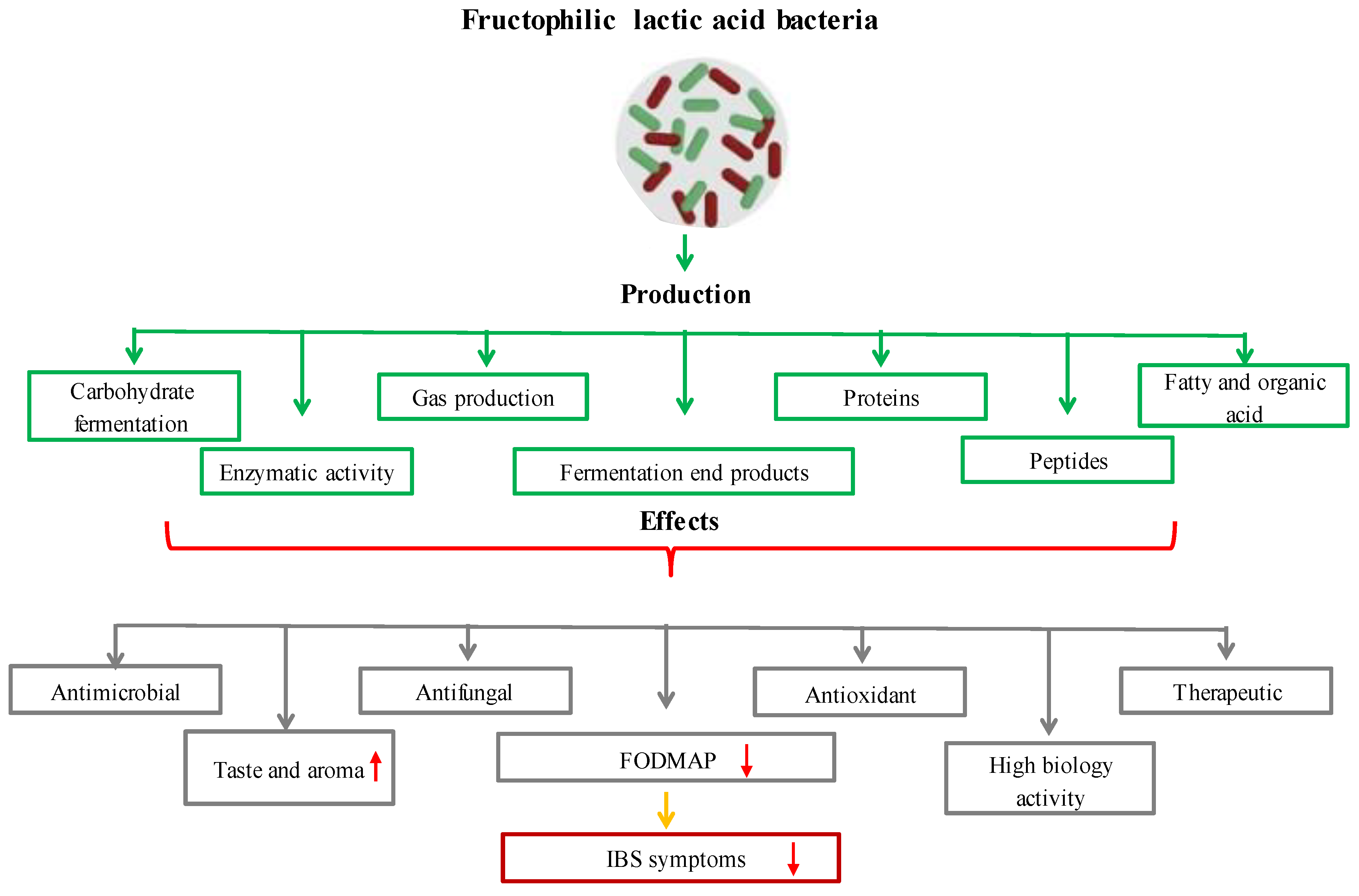

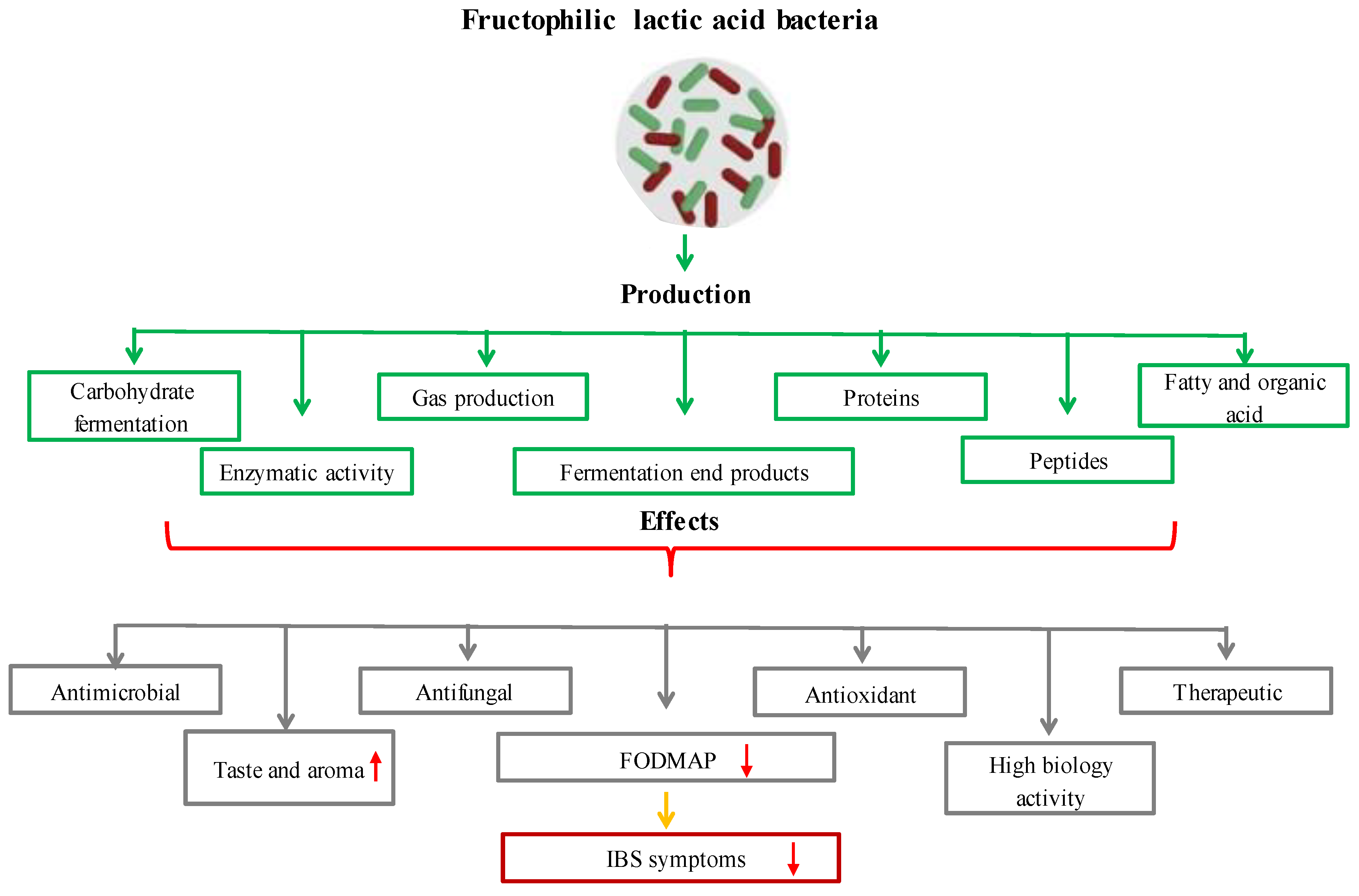

Recent research has revealed a brand-new breed of LAB known as fructophilic lactic acid bacteria (FLAB), which prefer fructose to glucose as a growth substrate [109][71]. FLAB is found in fructose-rich niches, which are the climatic and biological circumstances in which a species should survive, develop, and procreate [110][72]. Most FLAB grow best at pH 5–6 and temperatures of 30–35 °C [111][73]. FLAB are capable of carbohydrate fermentation (fermenting hexoses and pentoses), enzymatic activity, and gas, fermentation end products, proteins, peptides, oil and organic acid production. FLAB can have antimicrobial properties [111,112,113,114,115][73][74][75][76][77]. Due to the absence of the adhE gene, which codes for alcohol/acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, FLAB are heterofermentative LAB-type microbes that additionally create acetic acid and trace amounts of ethanol (ethanol, lactic acid, acetic acid = ratio 1:1:0.2, and mannitol) [116][78]. The plant secondary metabolite p-coumaric acid, which is a structural component of sporopollenin, the primary matrix that creates the exterior of pollen grains, is produced by FLAB using these [117,118][79][80]. FLAB have enzymes that can convert p-coumaric acid to 4-vinylphenol in the first step and 4-ethylphenol in the second stage [119][81]. These secondary metabolites are biologically active and have significant antioxidant capacities; they may also enhance the flavor of fermented foods [120][82]. At present, FLAB consist of two genera, Fructobacillus and Lactobacillus, and include six species, Fructobacillus durionis, Fructobacillus fructosus, Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus, Fructobacillus tropaeoli, Lactobacillus kunkeei, and Fructobacillus ficulneus, classified by Endo as obligatorily fructophilic, and only one species, namely Lactobacillus florum, is facultatively fructophilic [121][83]. FLAB are associated with the genera Leuconostoc, Convivina, Fructilactobacillus, Weissella, and Oenococcus [116][78]. New species with possible fructophilic characteristics are still being found, though [122][84]. FLAB have recently been discovered in the gastrointestinal tracts of animals that ingest fructose, including bumblebees, tropical fruit flies, and Camponotus ants. FLAB have previously been discovered in flowers, fruits, and fermented foods made from fruit [123][85]. Fermentation and LAB together give food significant organoleptic, quality, and safety advantages. As a source of water-soluble vitamins, dietary fiber, phytosterols, phytochemicals, and minerals, fermented vegetables (such as cucumber, Korean sauerkraut, capers, carrots, and table olives) are crucial to human nutrition. A new generation of multifunctional-starting cultures can be used to produce products with greater usefulness while also improving quality and safety, reducing economic losses and spoilage, and improving process control [124][86]. Given that they contain various LAB, certain fermented fruits and vegetables can be employed as a potential source of probiotics. As a whole, traditionally fermented fruits and vegetables may provide health benefits in addition to acting as a dietary supplement [125][87]. One can divide the FLAB into two categories. The first group includes the representatives Fructobacillus fructosus and Lactobacillus kunkeei as well as the partially related Lactobacillus apinorum and Lactobacillus florum, which are linked to flowers, grapes, wine, and insects. The second group, which consists of the bacteria Fructobacillus ficulneuses, Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus, and Fructobacillus durionis, is connected to ripe fruit and fruit fermentation (except grapes and wines). Between the two categories can be found Fructobacillus tropaeoli, which is present in flowers, fruits, and fruit fermentation. FLAB are referred to as promising microorganisms that can improve human health [126][88]. The evaluation of FLAB’s advantageous traits has gained attention due to the possible use of these novel probiotics [111][73]. FLAB strains are mostly obtained from settings high in fructose, such as the honeybee microbiome and bee products (Lactobacillus kunkeei and Fructobacillus fructosus). There is only one report of the isolation and identification of the relatively new FLAB strain Lactobacillus apinorum in bees [126][88]. In this investigation, samples of pollen and bee bread were used to isolate 27 distinct strains of four FLAB species. FLAB strains displayed high levels of autoaggregation and hydrophobicity in terms of functional characteristics. Importantly, it was discovered that the strains of Lactobacillus kunkeei and Fructobacillus fructosus had low levels of bile salt output and limited pH tolerance. The significance of FLAB strains’ functional roles for upcoming applications is increased by their high levels of antibacterial and antifungal activity [127][89]. A different study found that specific Lactobacillus kunkeei strains had antibacterial effects on honeybee larvae that were afflicted with the foulbrood disease Melissococcus plutonius [128,129][90][91]. Another study found that FLAB played a significant role in honey production by bees and were abundant in fresh honey. These bacteria reside in the microbiome of honeybees. It was also noted that fresh honey would soon be the best alternative for wound healing due to the antibacterial and therapeutic qualities of FLAB [130][92]. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other functional bowel diseases have been linked to the consumption of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP). A study indicated that by fermenting wheat dough, FLAB significantly lowered the number of FODMAPs present in it [131][93]. Wine flavor and aroma can be improved by Lactobacillus florum, which produces the genes for citrate lyase, phenolic acid decarboxylase, and malolactic enzyme [132][94]. Another study found that the fermentation of plant meals by Lactobacillus florum 2F resulted in the production of two polyols, erythritol and mannitol [133][95]. Fructobacillus durionis was found in tempoyak, a fermented condiment made from the pulp of durian [134][96]. The formation of flavor and aroma was influenced by the fermentation of cocoa beans by the bacteria Fructobacillus durionis, Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus, Fructobacillus ficulneus, and Fructobacillus tropaeoli [135][97].

Figure 5. The effects of functional and metabolic properties of FLAB on health and food production.

References

- Brodmann, T.; Endo, A.; Gueimonde, M.; Vinderola, G.; Kneifel, W.; de Vos, W.M.; Salminen, S.; Gómez-Gallego, C. Safety of Novel Microbes for Human Consumption: Practical Examples of Assessment in the European Union. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1725.

- Ariyoshi, T.; Hagihara, M.; Takahashi, M.; Mikamo, H. Effect of Clostridium butyricum on Gastrointestinal Infections. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 483.

- Ariyoshi, T.; Hagihara, M.; Tomono, S.; Eguchi, S.; Minemura, A.; Miura, D.; Oka, K.; Takahashi, M.; Yamagishi, Y.; Mikamo, H. Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 Modifies Bacterial Composition under Antibiotic-Induced Dysbiosis for the Activation of Interactions via Lipid Metabolism between the Gut Microbiome and the Host. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1065.

- Kim, D.-H.; Yoon, J.-J.; Kim, S.-H.; Park, J.-H. Acceleration of lactate-utilizing pathway for enhancing biohydrogen production by magnetite supplementation in Clostridium butyricum. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127448.

- Martins, F.F.; Liberato, V.d.S.; Ribeiro, C.M.S.; Coelho, M.A.Z.; Ferreira, T.F. Low-cost medium for 1, 3-propanediol production from crude glycerol by Clostridium butyricum. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2020, 14, 1125–1134.

- Szymanowska-Powałowska, D.; Orczyk, D.; Leja, K. Biotechnological potential of Clostridium butyricum bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2014, 45, 892–901.

- Ortigueira, J.; Martins, L.; Pacheco, M.; Silva, C.; Moura, P. Improving the non-sterile food waste bioconversion to hydrogen by microwave pretreatment and bioaugmentation with Clostridium butyricum. Waste Manag. 2019, 88, 226–235.

- Zhu, C.; Fang, B.; Wang, S. Effects of culture conditions on the kinetic behavior of 1, 3-propanediol fermentation by Clostridium butyricum with a kinetic model. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 212, 130–137.

- Liberato, V.S.; Martins, F.F.; Ribeiro, C.M.S.; Coelho, M.A.Z.; Ferreira, T.F. Two-waste culture medium to produce 1, 3-propanediol through a wild Clostridium butyricum strain. Fuel 2022, 322, 124202.

- Arisht, S.N.; Roslan, R.; Gie, G.A.; Mahmod, S.S.; Sajab, M.S.; Lay, C.-H.; Wu, S.-Y.; Ding, G.-T.; Jamali, N.S.; Jahim, J.M. Effect of nano zero-valent iron (nZVI) on biohydrogen production in anaerobic fermentation of oil palm frond juice using Clostridium butyricum JKT37. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 154, 106270.

- Masset, J.; Hiligsmann, S.; Hamilton, C.; Beckers, L.; Franck, F.; Thonart, P. Effect of pH on glucose and starch fermentation in batch and sequenced-batch mode with a recently isolated strain of hydrogen-producing Clostridium butyricum CWBI1009. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 3371–3378.

- Gupta, P.; Kumar, M.; Gupta, R.P.; Puri, S.K.; Ramakumar, S. Fermentative reforming of crude glycerol to 1, 3-propanediol using Clostridium butyricum strain L4. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133426.

- Sun, Y.-Q.; Shen, J.-T.; Yan, L.; Zhou, J.-J.; Jiang, L.-L.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, J.-L.; Feng, E.; Xiu, Z.-L. Advances in bioconversion of glycerol to 1, 3-propanediol: Prospects and challenges. Process Biochem. 2018, 71, 134–146.

- Kumar, V.; Park, S. Potential and limitations of Klebsiella pneumoniae as a microbial cell factory utilizing glycerol as the carbon source. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 150–167.

- Zhou, S.; Lama, S.; Sankaranarayanan, M.; Park, S. Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas denitrificans for the 1, 3-propanediol production from glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 121933.

- Liberato, V.; Benevenuti, C.; Coelho, F.; Botelho, A.; Amaral, P.; Pereira Jr, N.; Ferreira, T. Clostridium sp. as bio-catalyst for fuels and chemicals production in a biorefinery context. Catalysts 2019, 9, 962.

- Chassard, C.; Delmas, E.; Lawson, P.A.; Bernalier-Donadille, A. Bacteroides xylanisolvens sp. nov., a xylan-degrading bacterium isolated from human faeces. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 1008–1013.

- Narushima, S.; Itoh, K.; Takamine, F.; Uchida, K. Absence of cecal secondary bile acids in gnotobiotic mice associated with two human intestinal bacteria with the ability to dehydroxylate bile acids in vitro. Microbiol. Immunol. 1999, 43, 893–897.

- Hosseini, E.; Grootaert, C.; Verstraete, W.; Van de Wiele, T. Propionate as a health-promoting microbial metabolite in the human gut. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 245–258.

- Dasgupta, S.; Kasper, D.L. Novel Tools for Modulating Immune Responses in the Host—Polysaccharides from the Capsule of Commensal Bacteria. Adv. Immunol. 2010, 106, 61–91.

- Ulsemer, P.; Toutounian, K.; Schmidt, J.; Karsten, U.; Goletz, S. Preliminary safety evaluation of a new Bacteroides xylanisolvens isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 528–535.

- Ulsemer, P.; Toutounian, K.; Schmidt, J.; Leuschner, J.; Karsten, U.; Goletz, S. Safety assessment of the commensal strain Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2012, 62, 336–346.

- Hooper, L.V.; Midtvedt, T.; Gordon, J.I. How host-microbial interactions shape the nutrient environment of the mammalian intestine. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22, 283.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific Opinion on the safety of ‘heat-treated milk products fermented with Bacteroides xylanisolvens DSM 23964′as a novel food. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 3956.

- Derrien, M.; Vaughan, E.E.; Plugge, C.M.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1469–1476.

- Xing, J.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Miao, S.; Xiong, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G. Comparative genomic and functional analysis of Akkermansia muciniphila and closely related species. Genes Genom. 2019, 41, 1253–1264.

- Derrien, M.; Collado, M.C.; Ben-Amor, K.; Salminen, S.; de Vos, W.M. The Mucin degrader Akkermansia muciniphila is an abundant resident of the human intestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1646–1648.

- Everard, A.; Belzer, C.; Geurts, L.; Ouwerkerk, J.P.; Druart, C.; Bindels, L.B.; Guiot, Y.; Derrien, M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Delzenne, N.M. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9066–9071.

- Derrien, M.; Belzer, C.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila and its role in regulating host functions. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 171–181.

- Aggarwal, V.; Sunder, S.; Verma, S.R. Disease-associated dysbiosis and potential therapeutic role of Akkermansia muciniphila, a mucus degrading bacteria of gut microbiome. Folia Microbiol. 2022, 1–14.

- Kosciow, K.; Deppenmeier, U. Characterization of three novel β-galactosidases from Akkermansia muciniphila involved in mucin degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 331–340.

- Png, C.W.; Lindén, S.K.; Gilshenan, K.S.; Zoetendal, E.G.; McSweeney, C.S.; Sly, L.I.; McGuckin, M.A.; Florin, T.H. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augmentin vitroutilization of mucin by other bacteria. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2010, 105, 2420–2428.

- Kostopoulos, I.; Elzinga, J.; Ottman, N.; Klievink, J.T.; Blijenberg, B.; Aalvink, S.; Boeren, S.; Mank, M.; Knol, J.; de Vos, W.M. Akkermansia muciniphila uses human milk oligosaccharides to thrive in the early life conditions in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14330.

- Meng, X.; Wang, W.; Lan, T.; Yang, W.; Yu, D.; Fang, X.; Wu, H. A purified aspartic protease from Akkermansia muciniphila plays an important role in degrading Muc2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 72.

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, J.; Hao, Y.; Zhou, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.; Zeng, F.; Hu, J. Akkermansia muciniphila plays critical roles in host health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 1–19.

- Ottman, N.; Geerlings, S.Y.; Aalvink, S.; de Vos, W.M.; Belzer, C. Action and function of Akkermansia muciniphila in microbiome ecology, health and disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 31, 637–642.

- Ekici, L.; Polat, H. Akkermansia muciniphila: Obezite ve Diyabetten Korunmada Yeni Bir Alternatif Olabilir mi? Avrupa Bilim Ve Teknol. Derg. 2019, 16, 533–543.

- Zhai, Q.; Feng, S.; Arjan, N.; Chen, W. A next generation probiotic, Akkermansia muciniphila. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3227–3236.

- Plovier, H.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Depommier, C.; Van Hul, M.; Geurts, L.; Chilloux, J.; Ottman, N.; Duparc, T.; Lichtenstein, L. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 107–113.

- Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, R.; Cheng, R.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, M. The outer membrane protein Amuc_1100 of Akkermansia muciniphila promotes intestinal 5-HT biosynthesis and extracellular availability through TLR2 signalling. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 3597–3610.

- Mou, L.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Liao, H.; Liu, M.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Deng, D. Crystal structure of monomeric Amuc_1100 from Akkermansia muciniphila. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2020, 76, 168–174.

- Wong, N.; Fam, B.C.; Cempako, G.R.; Steinberg, G.R.; Walder, K.; Kay, T.W.; Proietto, J.; Andrikopoulos, S. Deficiency in interferon-γ results in reduced body weight and better glucose tolerance in mice. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3690–3699.

- Greer, R.L.; Dong, X.; Moraes, A.C.F.; Zielke, R.A.; Fernandes, G.R.; Peremyslova, E.; Vasquez-Perez, S.; Schoenborn, A.A.; Gomes, E.P.; Pereira, A.C. Akkermansia muciniphila mediates negative effects of IFNγ on glucose metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13329.

- Xu, Y.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.-Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y. Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in obesity: Interactions with lipid metabolism, immune response and gut systems. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 219.

- Abuqwider, J.N.; Mauriello, G.; Altamimi, M. Akkermansia muciniphila, a new generation of beneficial microbiota in modulating obesity: A systematic review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1098.

- Zhang, J.; Ni, Y.; Qian, L.; Fang, Q.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, M.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, J.; Hou, X. Decreased abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila leads to the impairment of insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis in lean type 2 diabetes. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100536.

- Cani, P.D.; Geurts, L.; Matamoros, S.; Plovier, H.; Duparc, T. Glucose metabolism: Focus on gut microbiota, the endocannabinoid system and beyond. Diabetes Metab. 2014, 40, 246–257.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. MDG, an Ophiopogon japonicus polysaccharide, inhibits non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by regulating the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 196, 23–34.

- Ghaffari, S.; Abbasi, A.; Somi, M.H.; Moaddab, S.Y.; Nikniaz, L.; Kafil, H.S.; Ebrahimzadeh Leylabadlo, H. Akkermansia muciniphila: From its critical role in human health to strategies for promoting its abundance in human gut microbiome. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 3, 1–21.

- Shin, N.-R.; Lee, J.-C.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Whon, T.W.; Lee, M.-S.; Bae, J.-W. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut 2014, 63, 727–735.

- Yoon, H.S.; Cho, C.H.; Yun, M.S.; Jang, S.J.; You, H.J.; Kim, J.-h.; Han, D.; Cha, K.H.; Moon, S.H.; Lee, K. Akkermansia muciniphila secretes a glucagon-like peptide-1-inducing protein that improves glucose homeostasis and ameliorates metabolic disease in mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 563–573.

- Bae, M.; Cassilly, C.D.; Liu, X.; Park, S.-M.; Tusi, B.K.; Chen, X.; Kwon, J.; Filipčík, P.; Bolze, A.S.; Liu, Z. Akkermansia muciniphila phospholipid induces homeostatic immune responses. Nature 2022, 608, 168–173.

- Kim, J.-S.; Kang, S.W.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, J.-S. The evolution and competitive strategies of Akkermansia muciniphila in gut. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2025017.

- Kumar, R.; Kane, H.; Wang, Q.; Hibberd, A.; Jensen, H.M.; Kim, H.-S.; Bak, S.Y.; Auzanneau, I.; Bry, S.; Christensen, N. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Species of Genus Akkermansia with Metabolic Health Effects in a Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model. Cells 2022, 11, 2084.

- Turck, D.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Kearney, J.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; Pelaez, C.; et al. Safety of heat-killed Mycobacterium setense manresensis as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2019, 17, e05824.

- Johansen, M.D.; Kremer, L. CFTR depletion confers hypersusceptibility to Mycobacterium fortuitum in a zebrafish model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 357.

- Zulu, M.; Monde, N.; Nkhoma, P.; Malama, S.; Munyeme, M. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in humans, animals, and water in Zambia: A systematic review. Front. Trop. Dis. 2021, 2, 9.

- Pereira, A.C.; Ramos, B.; Reis, A.C.; Cunha, M.V. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: Molecular and physiological bases of virulence and adaptation to ecological niches. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1380.

- Thornton, C.S.; Mellett, M.; Jarand, J.; Barss, L.; Field, S.K.; Fisher, D.A. The respiratory microbiome and nontuberculous mycobacteria: An emerging concern in human health. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 200299.

- Lee, G.J.; Lee, H.-M.; Kim, T.S.; Kim, J.K.; Sohn, K.M.; Jo, E.-K. Mycobacterium fortuitum induces A20 expression that impairs macrophage inflammatory responses. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftw015.

- Lamy, B.; Marchandin, H.; Hamitouche, K.; Laurent, F. Mycobacterium setense sp. nov., a Mycobacterium fortuitum-group organism isolated from a patient with soft tissue infection and osteitis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 486–490.

- Keikha, M. Case report of isolation of Mycobacterium setense from a hospital water supply. Environ. Dis. 2018, 3, 52.

- Rech, G.; Vilaplana, C.; Velasco, J.; Pluvinet, R.; Santín, S.; Prat, C.; Julián, E.; Alcaide, F.; Comas, I.; Sumoy, L. Draft genome sequences of Mycobacterium setense type strain DSM-45070 and the nonpathogenic strain manresensis, isolated from the Bank of the Cardener River in Manresa, Catalonia, Spain. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e01485-14.

- Comberiati, P.; Di Cicco, M.; Paravati, F.; Pelosi, U.; Di Gangi, A.; Arasi, S.; Barni, S.; Caimmi, D.; Mastrorilli, C.; Licari, A. The role of gut and lung microbiota in susceptibility to tuberculosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12220.

- Koizumi, S.-i.; Wakita, D.; Sato, T.; Mitamura, R.; Izumo, T.; Shibata, H.; Kiso, Y.; Chamoto, K.; Togashi, Y.; Kitamura, H. Essential role of Toll-like receptors for dendritic cell and NK1. 1+ cell-dependent activation of type 1 immunity by Lactobacillus pentosus strain S-PT84. Immunol. Lett. 2008, 120, 14–19.

- Korn, T.; Bettelli, E.; Oukka, M.; Kuchroo, V.K. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 485–517.

- Cardona, P.; Marzo-Escartin, E.; Tapia, G.; Díaz, J.; García, V.; Varela, I.; Vilaplana, C.; Cardona, P.-J. Oral administration of heat-killed Mycobacterium manresensis delays progression toward active tuberculosis in C3HeB/FeJ mice. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1482.

- Garrido-Amaro, C.; Cardona, P.; Gassó, D.; Arias, L.; Velarde, R.; Tvarijonativiciute, A.; Serrano, E.; Cardona, P.-J. Protective Effect of Intestinal Helminthiasis Against Tuberculosis Progression Is Abrogated by Intermittent Food Deprivation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1233.

- Tukvadze, N.; Cardona, P.; Vashakidze, S.; Shubladze, N.; Avaliani, Z.; Vilaplana, C.; Cardona, P.-J. Development of the food supplement Nyaditum resae as a new tool to reduce the risk of tuberculosis development. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2016, 5, S101–S102.

- Cardona, P.-J. The progress of therapeutic vaccination with regard to tuberculosis. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1536.

- Endo, A.; Futagawa-Endo, Y.; Dicks, L.M. Isolation and characterization of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria from fructose-rich niches. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 32, 593–600.

- Endo, A. Fructophilic lactic acid bacteria inhabit fructose-rich niches in nature. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2012, 23, 18563.

- Muslimah, R.; Mahatmanto, T.; Kusnadi, J.; Murdiyatmo, U. General methods to isolate, characterize, select, and identify fructophilic lactic acid bacteria from fructose-rich environments—A mini-review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Green Agro-industry and Bioeconomy, Malang, Indonesia, 6–7 July 2021; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. p. 012079.

- Pachla, A.; Wicha, M.; Ptaszyńska, A.A.; Borsuk, G.; Trokenheim, Ł.Ł.; Małek, W. The molecular and phenotypic characterization of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria isolated from the guts of Apis mellifera L. derived from a Polish apiary. J. Appl. Genet. 2018, 59, 503–514.

- Asenjo, F.; Olmos, A.; Henríquez-Piskulich, P.; Polanco, V.; Aldea, P.; Ugalde, J.A.; Trombert, A.N. Genome sequencing and analysis of the first complete genome of Lactobacillus kunkeei strain MP2, an Apis mellifera gut isolate. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1950.

- Butler, É.; Oien, R.F.; Lindholm, C.; Olofsson, T.C.; Nilson, B.; Vásquez, A. A pilot study investigating lactic acid bacterial symbionts from the honeybee in inhibiting human chronic wound pathogens. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 729–737.

- Olofsson, T.C.; Butler, È.; Markowicz, P.; Lindholm, C.; Larsson, L.; Vásquez, A. Lactic acid bacterial symbionts in honeybees–an unknown key to honey’s antimicrobial and therapeutic activities. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 668–679.

- Dicks, L.; Endo, A. Are fructophilic lactic acid bacteria (FLAB) beneficial to humans? Benef. Microbes 2022, 13, 3–11.

- Ulusoy, E.; Kolayli, S. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of Anzer bee pollen. J. Food Biochem. 2014, 38, 73–82.

- Mao, W.; Schuler, M.A.; Berenbaum, M.R. Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8842–8846.

- De Las Rivas, B.; Rodríguez, H.C.; Curiel, J.A.; Landete, J.M.A.; Munoz, R. Molecular screening of wine lactic acid bacteria degrading hydroxycinnamic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 490–494.

- Huang, J.; de Paulis, T.; May, J.M. Antioxidant effects of dihydrocaffeic acid in human EA. hy926 endothelial cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004, 15, 722–729.

- Endo, A.; Tanizawa, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Maeno, S.; Kumar, H.; Shiwa, Y.; Okada, S.; Yoshikawa, H.; Dicks, L.; Nakagawa, J. Comparative genomics of Fructobacillus spp. and Leuconostoc spp. reveals niche-specific evolution of Fructobacillus spp. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1117.

- Endo, A.; Okada, S. Reclassification of the genus Leuconostoc and proposals of Fructobacillus fructosus gen. nov., comb. nov., Fructobacillus durionis comb. nov., Fructobacillus ficulneus comb. nov. and Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2195–2205.

- Gustaw, K.; Michalak, M.; Polak-Borecka, M.; Wasko, A. Fruktofilne bakterie kwasu mlekowego (FLAB)–Nowa grupa heterofermentatywnych mikroorganizmów ze środowiska roślinnego. Postępy Mikrobiol. 2017, 56, 56–66.

- Bautista-Gallego, J.; Medina, E.; Sánchez, B.; Benítez-Cabello, A.; Arroyo-López, F.N. Role of lactic acid bacteria in fermented vegetables. Grasas Aceites 2020, 71, e358.

- Swain, M.R.; Anandharaj, M.; Ray, R.C.; Rani, R.P. Fermented fruits and vegetables of Asia: A potential source of probiotics. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 250424.

- Endo, A.; Maeno, S.; Tanizawa, Y.; Kneifel, W.; Arita, M.; Dicks, L.; Salminen, S. Fructophilic lactic acid bacteria, a unique group of fructose-fermenting microbes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01290-18.

- Ispirli, H.; Dertli, E. Detection of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria (FLAB) in bee bread and bee pollen samples and determination of their functional roles. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15414.

- Neveling, D.P.; Endo, A.; Dicks, L.M. Fructophilic Lactobacillus kunkeei and Lactobacillus brevis isolated from fresh flowers, bees and bee-hives. Curr. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 507–515.

- Iorizzo, M.; Ganassi, S.; Albanese, G.; Letizia, F.; Testa, B.; Tedino, C.; Petrarca, S.; Mutinelli, F.; Mazzeo, A.; De Cristofaro, A. Antimicrobial Activity from Putative Probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria for the Biological Control of American and European Foulbrood Diseases. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 236.

- Pachla, A.; Ptaszyńska, A.A.; Wıcha, M.; Oleńska, E.; Małek, W. Fascinating fructophilic lactic acid bacteria associated with various fructose-rich niches. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Sect. C Biol. 2019, 72, 41–50.

- Acín Albiac, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Filannino, P.; Cantatore, V.; Gobbetti, M. How fructophilic lactic acid bacteria may reduce the FODMAPs content in wheat-derived baked goods: A proof of concept. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 182.

- Mtshali, P.S.; Divol, B.; Du Toit, M. Identification and characterization of Lactobacillus florum strains isolated from South African grape and wine samples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 106–113.

- Endo, A.; Futagawa-Endo, Y.; Sakamoto, M.; Kitahara, M.; Dicks, L.M. Lactobacillus florum sp. nov., a fructophilic species isolated from flowers. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2478–2482.

- Chuah, L.-O.; Shamila-Syuhada, A.K.; Liong, M.T.; Rosma, A.; Thong, K.L.; Rusul, G. Physio-chemical, microbiological properties of tempoyak and molecular characterisation of lactic acid bacteria isolated from tempoyak. Food Microbiol. 2016, 58, 95–104.

- Ouattara, H.D.; Ouattara, H.G.; Droux, M.; Reverchon, S.; Nasser, W.; Niamke, S.L. Lactic acid bacteria involved in cocoa beans fermentation from Ivory Coast: Species diversity and citrate lyase production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 256, 11–19.

More