Multidrug resistance (MDR) among pathogens and the associated infections represent an escalating global public health problem that translates into raised mortality and healthcare costs. MDR bacteria, with both intrinsic abilities to resist antibiotics treatments and capabilities to transmit genetic material coding for further resistance to other bacteria, dramatically decrease the number of available effective antibiotics, especially in nosocomial environments. Moreover, the capability of several bacterial species to form biofilms (BFs) is an added alarming mechanism through which resistance develops. BF, made of bacterial communities organized and incorporated into an extracellular polymeric matrix, self-produced by bacteria, provides protection from the antibiotics’ action, resulting in the antibiotic being ineffective.

- multidrug resistance

- bacterial BFs

- fungi BFs

- P. aeruginosa BFs

- cationic antimicrobial agents

1. Introduction to Microbial Resistance

| Name of Bacterium | Drug(s) Resistant to | Typical Disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones | UTI, BSI | ||

| K. pneumoniae | Cephalosporins, carbapenems | Pneumonia, BSI, UTI | ||

| S. aureus | Methicillin | Wound, BSI | ||

| S. pneumoniae | Penicillin | Pneumonia, meningitis, otitis | ||

| Nontyphoidal Salmonella | Fluoroquinolones | Foodborne diarrhea, BSI | ||

| Shigella | spp. | Fluoroquinolones | Diarrhea * | |

| N. gonorrhoeae | Cephalosporins | Gonorrhea | ||

| M. tuberculosis | Rifampicin, isoniazid, fluoroquinolone | Tuberculosis | ||

| Name of Fungi | ||||

| Candida | spp. | Fluconazole, echinocandins [7] | Candidiasis | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | Fluconazole [8] | Cryptococcosis | ||

| Aspergillus | spp. | Azoles [9] | Aspergillosis | |

| Scopulariopsis | spp. | Onychomycosis | Amphotericin B, flucytosine, azoles [10] | Onychomycosis |

| Name of Virus | ||||

| Cytomegalovirus | (CMV) | Ganciclovir, foscarnet [11] | AIDS and oncology patients | |

| Herpes simplex virus | (HSV) | Acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir [12] | Herpes simplex | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | (HIV) | Antiretroviral drugs [13] | AIDS | |

| Influenza virus | Amantadine, rimantadine, neuraminidase inhibitors [14] | Influenza | ||

| Varicella zoster virus | Acyclovir, valacyclovir [12] | Chicken pox | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | (HBV) | Lamivudine [15] |

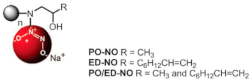

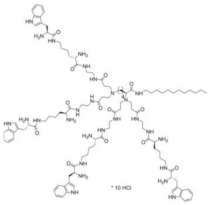

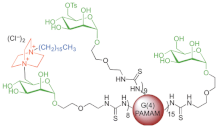

Cationic Dendrimers

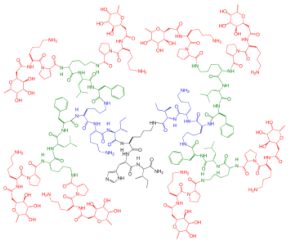

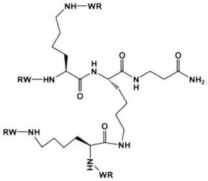

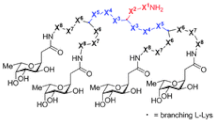

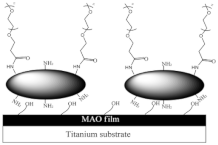

Dendrimers were first synthesized in the mid-1980s, but their use as antibacterial agents, mimicking the action of NAMPs for use as drugs, surface coating agents, or drug-delivery systems, has only recently been recognized [62,63,64,68,69,70,71,72][29][36][40][41][42][43][44][45]. In the last decade, dendrimers have mainly been synthesized for the treatment of infections caused by MDR pathogens and some of these have been shown to have antibiofilm action [151,152][46][47]. The most used and studied commercial dendrimers as antibacterial agents are poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) and polypropylene imines (PPIs), which have shown wide activity in vitro; however, unless they are properly modified to improve their biodegradability, reduce their susceptibility to opsonization and toxicity against eukaryotic cells, and fast clearance, they are not clinically applicable [70,71,72][42][43][44]. Moreover, polymers such as linear and branched poly (ethylene imine)s (PEIs), in addition to requiring minor costs for production, although with less perfect architectures than PAMAMs and PPIs, are known for their ability to enter cells or permeabilize cell membranes. Accordingly, while a large number of studies have focused on the antibacterial activity of water-soluble PEI derivatives containing quaternized ammonium salt groups with long alkyl or aromatic groups, others reported the application of water-insoluble hydrophobic PEIs, including nanoparticles, as antibacterial coatings [153][48]. To improve and therefore obtain CDs with better characteristics, particular attention was paid to the synthesis of biodegradable polyester-based dendrimer scaffolds, peripherally modified with suitable amino acids, thus achieving shells that are highly cationic and conferring the obtained dendrimer NPs’ potent antibacterial properties [63,70,71,72,154,155][29][42][43][44][49][50]. In the worrying scenario where the weapons used to counteract MDR bacteria and above all infections sustained by BF-producing pathogens are dramatically decreased or non-existent, cationic dendrimer NPs could represent new valid promising tools for fighting MDR pathogens and also for the treatment of sustained BAIs of MDR BF-producing bacteria. The advantages associated with the use of cationic material with dendrimer structures mainly depend on their high multivalency deriving from their tree-like and generational structure, which allows a large abundance of active cationic moieties, thus greatly improving their antibacterial potency [63][29]. Aiming to inspire the realization of further synthetic strategies for developing new antibacterial dendrimers capable of inhibiting the first training and/or destroying mature BFs, wresearchers review the most recent investigations carried out to design and develop new antibiofilm dendrimer agents and the related results.2.2. Recently Reported Case Studies

Table 2 shows the structures representative of the main class of dendrimers engineered.| Dendrimers Structure | Name | Activity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2G3 | IC | 50 | = 0.025 µM | P. aeruginosa | (PA) LecB | ||

|

(RW) | 4D | Inactivate | E. coli | RP437 planktonic culture and BFs |

|||

|

FD2 | LD | 50 | LecB PA 0.14 µM | P. aeruginosa | BF formation (IC | 50 | = 10 mM) |

| D-FD2 | LD | 50 | LecB PA 0.66 µM |

|||||

|

PEGylated PAMAM Film on MAO Substrate | BF by PA (strain PAO1) and | S. aureus | (SA). | ||||

|

Nitric Oxide-Releasing amphiphilic PAMAM | Inhibited PA BFs | ||||||

|

14 | Inhibited | C. albicans | BF | ||||

|

G4 PAMAMs decorated with C | 16 | -DABCO | Inhibited | E. coli | and | B. cereus | BF |

|

PEGylated AgNPs covered with cationic carbosilane dendrons | Inhibited | E. coli | and | S. aureus | BF | ||

| Hepatitis B | ||||||||

| Name of Parasite | ||||||||

| Plasmodia | ||||||||

| spp. | Chloroquine, artemisinin, atovaquone [16] | Malaria | ||||||

| Leishmania | spp. | Pentavalent antimonials, miltefosine paromomycin, amphotericin B [17,18] | Pentavalent antimonials, miltefosine paromomycin, amphotericin B [17][18] |

Leishmaniasis | ||||

| Schistosomes | Praziquantel, oxamniquine [19,20] | Praziquantel, oxamniquine [19][20] | Schistosomiasis | |||||

| Entamoeba | Metronidazole [21] | Amoebiasis | ||||||

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Nitroimidazoles [22] | Trichomoniasis | ||||||

| Toxoplasma gondii | Artemisinin, atovaquone, sulfadiazine [23,24,25] | Artemisinin, atovaquone, sulfadiazine [23][24][25] | Toxoplasmosis |

2. Prevention and/or Eradication of BF by Dendrimers: A Possibility Still Little Explored

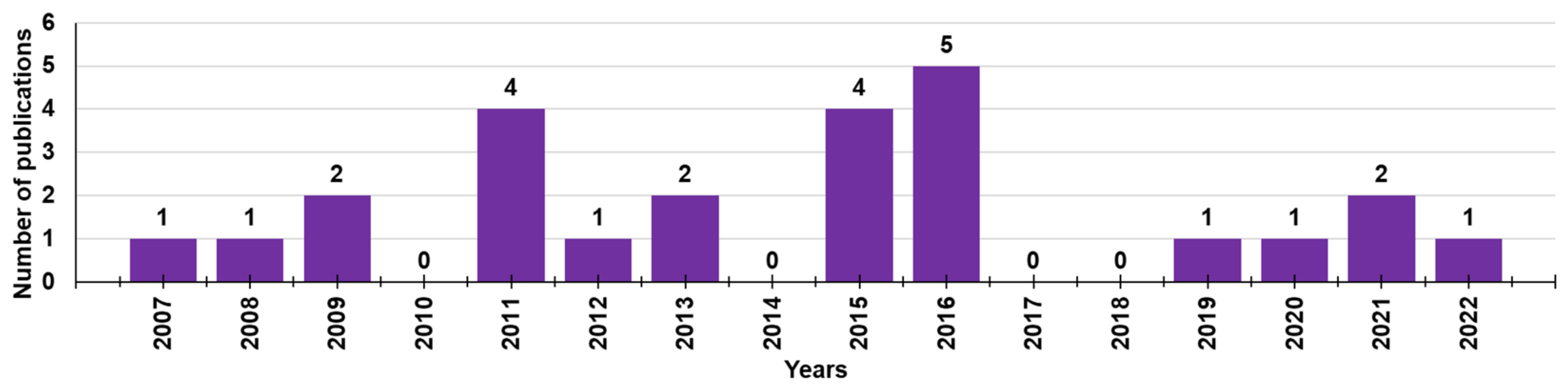

Although cationic dendrimers have been extensively studied as antibacterial agents with high potentiality, as shown by a search of Scopus using “cationic dendrimers” and “biofilm” as keywords, in the last 15 years (2007–2022), only 29 documents concerning this topic have been reported in the literature (Figure 1).

2.1. Antibacterial Cationic Macromolecules

Currently, there are few molecules under clinical development that are active against MDR pathogens and/or BF producers. Concerning the main agents in clinical development (Phase III) in 2020, only caspofungin, which is an antifungal drug, has been proven to inhibit the synthesis of polysaccharide components of the bacterial BF of S. aureus [144][28]. Concerning nanoparticles, some research groups are currently studying polymeric lipid nanoparticles, involving the conjugation of rhamnolipids (biosurfactants secreted by the pathogen P. aeruginosa) and polymer nanoparticles made of clarithromycin encapsulated in a polymeric core of chitosan. By the same principle, rhamnolipid-coated silver and iron oxide NPs have been developed, which have been shown to be effective in eradicating S. aureus and P. aeruginosa BFs [144][28]. Therefore, to counteract the phenomenon of drug resistance and meet the urgent need for new antibacterial agents that are also active in infections sustained by BF cells, the search for alternative therapeutic strategies capable of acting under mechanisms different from those of conventional drugs is a daily challenge of researchers in this field. In this regard, various natural cationic molecules called antimicrobial peptides (NAMPs) have shown significant capabilities to limit or inhibit bacterial growth and represent excellent candidates for replacing current antibiotics that are no longer effective. The amphiphilic structure and the net positive charge of NAMPs are the two most important requisites necessary for antibacterial effects and decide their mechanism of action [63,145,146,147][29][30][31][32]. It has, in fact, been shown that NAMPs’ action causes the death of the bacterial cell in a non-specific way from the outside, without having to enter the bacterial cell and interact with its metabolic processes, which is likely to genetically mute the conferring of resistance [63,145][29][30]. The action of NAMPs on bacteria is rapid, causes depolarization and destabilization of the membranes, and generates pores that gradually lead to an increase in their permeability, with consequent leakage of essential cations and other cytoplasmic materials and cell death. Since it is not connected to mutable bacterial processes, this mechanism of action generally allows the cationic peptides to induce a lower development of resistance in the target cell compared to traditional antibiotics [63,145][29][30]. Although the main target of NAMPs is bacterial membranes, it has been reported that some of these cationic antimicrobial peptides, following the increased permeability of bacterial envelopes, could also enter the cell and irreversibly damage molecules, such as DNA, RNA, and enzymes, thus leading to an improvement in their original therapeutic efficacy [63,146,147,148,149][29][31][32][33][34]. Unfortunately, the in vivo application of NAMPs is hampered by their early inactivation by peptidases, their high hemolytic toxicity, and high costs of production. Based on this, in the last decades, inspired by NAMPs, new cationic antibacterial macromolecules, such as polymers, copolymers, and dendrimers, have been developed, with proven interesting antibacterial effects. Such macromolecules, unlike small antibacterial compounds, in addition to possess multivalence, have other several advantages, including a limited residual toxicity, greater long-term activity, greater chemical stability, and lesser tendency to develop resistance [63,147References

- Vadivelu, J. Microbial Pathogens and Strategies for Combating Them: Science, Technology and Education; Formatex Research Center: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013.

- Popęda, M.; Płuciennik, E.; Bednarek, A.K. Proteins in cancer resistance. Postępy Hig. Med. Do’swiadczalnej 2014, 68, 616–632.

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281.

- Alfei, S.; Caviglia, D.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Spallarossa, A.; Lusardi, M.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, A.M. Potent and Broad-Spectrum Bactericidal Activity of a Nanotechnologically Manipulated Novel Pyrazole. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 907.

- Nikaido, H. Multidrug Resistance in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 119–146.

- World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report: Early Implementation 2016–2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-151344-9.

- Loeffler, J.; Stevens, D.A. Antifungal drug resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36 (Suppl. 1), S31–S41.

- Rodero, L.; Mellado, E.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Salve, A.; Guelfand, L.; Cahn, P.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Davel, G.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L. G484S Amino Acid Substitution in Lanosterol 14-α Demethylase (ERG11) Is Related to Fluconazole Resistance in a Recurrent Cryptococcus neoformans Clinical Isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3653–3656.

- Howard, S.J.; Arendrup, M.C. Acquired Antifungal Drug Resistance in Aspergillus Fumigatus: Epidemiology and Detection. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, S90–S95.

- Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Gomez-Lopez, A.; Mellado, E.; Buitrago, M.J.; Monzón, A.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L. Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, a Fungal Pathogen Resistant to Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2339–2341.

- Lurain, N.S.; Chou, S. Antiviral Drug Resistance of Human Cytomegalovirus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 689–712.

- Wutzler, P. Antiviral Therapy of Herpes Simplex and Varicella-Zoster Virus Infections. Intervirology 1997, 40, 343–356.

- Cortez, K.J.; Maldarelli, F. Clinical Management of HIV Drug Resistance. Viruses 2011, 3, 347–378.

- Hurt, A.C. The Epidemiology and Spread of Drug Resistant Human Influenza Viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 8, 22–29.

- Suppiah, J.; Mohd Zain, R.; Haji Nawi, S.; Bahari, N.; Saat, Z. Drug-Resistance Associated Mutations in Polymerase (P) Gene of Hepatitis B Virus Isolated from Malaysian HBV Carriers. Hepat. Mon. 2014, 14, e13173.

- Bloland, P.B.; World Health Organization. Anti-Infective Drug Resistance Surveillance and Containment Team. Drug Resistance in Malaria. 2001. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66847 (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Vanaerschot, M.; Dumetz, F.; Roy, S.; Ponte-Sucre, A.; Arevalo, J.; Dujardin, J.-C. Treatment Failure in Leishmaniasis: Drug-Resistance or Another (Epi-) Phenotype? Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2014, 12, 937–946.

- Mohapatra, S. Drug Resistance in Leishmaniasis: Newer Developments. Trop. Parasitol. 2014, 4, 4–9.

- Fallon, P.G.; Doenhoff, M.J. Drug-Resistant Schistosomiasis: Resistance to Praziquantel and Oxamniquine Induced in Schistosoma mansoni in Mice Is Drug Specific. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994, 51, 83–88.

- Qi, L.; Cui, J. A Schistosomiasis Model with Praziquantel Resistance. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 2013, e945767.

- Bansal, D.; Malla, N.; Mahajan, R. Drug Resistance in Amoebiasis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2006, 123, 115–118.

- Muzny, C.A.; Schwebke, J.R. The Clinical Spectrum of Trichomonas Vaginalis Infection and Challenges to Management. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2013, 89, 423–425.

- McFadden, D.C.; Tomavo, S.; Berry, E.A.; Boothroyd, J.C. Characterization of Cytochrome b from Toxoplasma gondii and Qo Domain Mutations as a Mechanism of Atovaquone-Resistance. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000, 108, 1–12.

- Nagamune, K.; Moreno, S.N.J.; Sibley, L.D. Artemisinin-Resistant Mutants of Toxoplasma gondii Have Altered Calcium Homeostasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3816–3823.

- Doliwa, C.; Escotte-Binet, S.; Aubert, D.; Sauvage, V.; Velard, F.; Schmid, A.; Villena, I. Sulfadiazine Resistance in Toxoplasma gondii: No Involvement of Overexpression or Polymorphisms in Genes of Therapeutic Targets and ABC Transporters. Parasite 2013, 20, 19.

- Ullman, B. Multidrug Resistance and P-Glycoproteins in Parasitic Protozoa. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1995, 27, 77–84.

- Greenberg, R.M. New Approaches for Understanding Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Schistosomes. Parasitology 2013, 140, 1534–1546.

- Terreni, M.; Taccani, M.; Pregnolato, M. New Antibiotics for Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Strains: Latest Research Developments and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2671.

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M. From Nanobiotechnology, Positively Charged Biomimetic Dendrimers as Novel Antibacterial Agents: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2022.

- Melo, M.N.; Ferre, R.; Castanho, M.A.R.B. Antimicrobial Peptides: Linking Partition, Activity and High Membrane-Bound Concentrations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 245–250.

- Ahmed, T.A.E.; Hammami, R. Recent Insights into Structure–Function Relationships of Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12546.

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M. Positively Charged Polymers as Promising Devices against Multidrug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 1195.

- Chen, L.; Harrison, S.D. Cell-Penetrating Peptides in Drug Development: Enabling Intracellular Targets. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 821–825.

- Bechinger, B.; Gorr, S.-U. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 254–260.

- Jain, A.; Duvvuri, L.S.; Farah, S.; Beyth, N.; Domb, A.J.; Khan, W. Antimicrobial Polymers. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1969–1985.

- Alfei, S.; Grazia Signorello, M.; Schito, A.; Catena, S.; Turrini, F. Reshaped as Polyester-Based Nanoparticles, Gallic Acid Inhibits Platelet Aggregation, Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Multi-Resistant Gram-Positive Bacteria with an Efficiency Never Obtained. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 4148–4157.

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Domenicotti, C. Polyester-Based Dendrimer Nanoparticles Combined with Etoposide Have an Improved Cytotoxic and Pro-Oxidant Effect on Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 50.

- Alfei, S.; Catena, S.; Turrini, F. Biodegradable and Biocompatible Spherical Dendrimer Nanoparticles with a Gallic Acid Shell and a Double-Acting Strong Antioxidant Activity as Potential Device to Fight Diseases from “Oxidative Stress”. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 259–270.

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Zuccari, G.; Turrini, F.; Domenicotti, C. Dendrimer Nanodevices and Gallic Acid as Novel Strategies to Fight Chemoresistance in Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1243.

- Alfei, S.; Brullo, C.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, A.M. Pyrazole-Based Water-Soluble Dendrimer Nanoparticles as a Potential New Agent against Staphylococci. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 17.

- Schito, A.M.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, G.C.; Alfei, S. Efficacy of Ursolic Acid-Enriched Water-Soluble and Not Cytotoxic Nanoparticles against Enterococci. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1976.

- Schito, A.M.; Schito, G.C.; Alfei, S. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Cationic Amino Acid-Conjugated Dendrimers Loaded with a Mixture of Two Triterpenoid Acids. Polymers 2021, 13, 521.

- Schito, A.M.; Alfei, S. Antibacterial Activity of Non-Cytotoxic, Amino Acid-Modified Polycationic Dendrimers against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Other Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacteria. Polymers 2020, 12, 1818.

- Alfei, S.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, A.M. Bactericidal Activity of a Self-Biodegradable Lysine-Containing Dendrimer against Clinical Isolates of Acinetobacter Genus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7274.

- Wei, T.; Yu, Q.; Chen, H. Antibacterial Coatings: Responsive and Synergistic Antibacterial Coatings: Fighting against Bacteria in a Smart and Effective Way. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1970007.

- Mintzer, M.A.; Dane, E.L.; O’Toole, G.A.; Grinstaff, M.W. Exploiting Dendrimer Multivalency to Combat Emerging and Re-Emerging Infectious Diseases. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 342–354.

- Bahar, A.A.; Liu, Z.; Totsingan, F.; Buitrago, C.; Kallenbach, N.; Ren, D. Synthetic Dendrimeric Peptide Active against Biofilm and Persister Cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 8125–8135.

- Gibney, K.A.; Sovadinova, I.; Lopez, A.I.; Urban, M.; Ridgway, Z.; Caputo, G.A.; Kuroda, K. Poly(ethylene imine)s as antimicrobial agents with selective activity. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 1279–1289.

- Stenström, P.; Hjorth, E.; Zhang, Y.; Andrén, O.C.J.; Guette-Marquet, S.; Schultzberg, M.; Malkoch, M. Synthesis and In Vitro Evaluation of Monodisperse Amino-Functional Polyester Dendrimers with Rapid Degradability and Antibacterial Properties. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4323–4330.

- Schito, A.M.; Piatti, G.; Caviglia, D.; Zuccari, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Alfei, S. Bactericidal Activity of Non-Cytotoxic Cationic Nanoparticles against Clinically and Environmentally Relevant Pseudomonas Spp. Isolates. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1411.

- Johansson, E.M.V.; Crusz, S.A.; Kolomiets, E.; Buts, L.; Kadam, R.U.; Cacciarini, M.; Bartels, K.-M.; Diggle, S.P.; Cámara, M.; Williams, P.; et al. Inhibition and Dispersion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms by Glycopeptide Dendrimers Targeting the Fucose-Specific Lectin LecB. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 1249–1257.

- Kolomiets, E.; Swiderska, M.A.; Kadam, R.U.; Johansson, E.M.V.; Jaeger, K.-E.; Darbre, T.; Reymond, J.-L. Glycopeptide Dendrimers with High Affinity for the Fucose-Binding Lectin LecB from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 562–569.

- Hou, S.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Z.; Young, A.W.; Shi, Z.; Ren, D.; Kallenbach, N.R. Antimicrobial dendrimer active against Escherichia coli biofilms. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 5478–5481.

- Johansson, E.M.; Kadam, R.U.; Rispoli, G.; Crusz, S.A.; Bartels, K.-M.; Diggle, S.P.; Cámara, M.; Williams, P.; Jaeger, K.-E.; Darbre, T.; et al. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms with a Glycopeptide Dendrimer Containing D-Amino Acids. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 418–420.

- Kadam, R.U.; Bergmann, M.; Hurley, M.; Garg, D.; Cacciarini, M.; Swiderska, M.A.; Nativi, C.; Sattler, M.; Smyth, A.R.; Williams, P.; et al. A Glycopeptide Dendrimer Inhibitor of the Galactose-Specific Lectin LecA and of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10631–10635.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, C.; Kallenbach, N.R.; Ren, D. Control of Bacterial Persister Cells by Trp/Arg-Containing Antimicrobial Peptides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 4878–4885.

- Wang, L.; Erasquin, U.J.; Zhao, M.; Ren, L.; Zhang, M.Y.; Cheng, G.J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, C. Stability, Antimicrobial Activity, and Cytotoxicity of Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimers on Titanium Substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 2885–2894.

- Scorciapino, M.A.; Pirri, G.; Vargiu, A.V.; Ruggerone, P.; Giuliani, A.; Casu, M.; Buerck, J.; Wadhwani, P.; Ulrich, A.S.; Rinaldi, A.C. A Novel Dendrimeric Peptide with Antimicrobial Properties: Structure-Function Analysis of SB056. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 1039–1048.

- Lu, Y.; Slomberg, D.L.; Shah, A.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Amphiphilic Poly(Amidoamine) (PAMAM) Dendrimers as Antibacterial Agents. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3589–3598.

- Reymond, J.L.; Bergmann, M.; Darbre, T. Glycopeptide dendrimers as Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm inhibitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4814–4822.

- Zielinska, P.; Staniszewska, M.; Bondaryk, M.; Koronkiewicz, M.; Urbanczyk-Lipkowska, Z. Design and Studies of Multiple Mechanism of Anti-Candida Activity of a New Potent Trp-Rich Peptide Dendrimers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 105, 106–119.

- Lara, H.H.; Romero-Urbina, D.G.; Pierce, C.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Arellano-Jiménez, M.J.; Jose-Yacaman, M. Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on Candida albicans Biofilms: An Ultrastructural Study. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 13, 91.

- Worley, B.V.; Schilly, K.M.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Anti-Biofilm Efficacy of Dual-Action Nitric Oxide-Releasing Alkyl Chain Modified Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimers. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 1573–1583.

- Visini, R.; Jin, X.; Bergmann, M.; Michaud, G.; Pertici, F.; Fu, O.; Pukin, A.; Branson, T.R.; Thies-Weesie, D.M.E.; Kemmink, J.; et al. Structural Insight into Multivalent Galactoside Binding to Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lectin LecA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2455–2462.

- Backlund, C.J.; Worley, B.V.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Anti-Biofilm Action of Nitric Oxide-Releasing Alkyl-Modified Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimers against Streptococcus Mutans. Acta Biomater. 2016, 29, 198–205.

- Bergmann, M.; Michaud, G.; Visini, R.; Jin, X.; Gillon, E.; Stocker, A.; Imberty, A.; Darbre, T.; Reymond, J.-L. Multivalency Effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Inhibition and Dispersal by Glycopeptide Dendrimers Targeting Lectin LecA. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 138–148.

- Michaud, G.; Visini, R.; Bergmann, M.; Salerno, G.; Bosco, R.; Gillon, E.; Richichi, B.; Nativi, C.; Imberty, A.; Stocker, A.; et al. Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Using Glycopeptide Dendrimers. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 166–182.

- Batoni, G.; Casu, M.; Giuliani, A.; Luca, V.; Maisetta, G.; Mangoni, M.L.; Manzo, G.; Pintus, M.; Pirri, G.; Rinaldi, A.C.; et al. Rational Modification of a Dendrimeric Peptide with Antimicrobial Activity: Consequences on Membrane-Binding and Biological Properties. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 887–900.

- Vankoten, H.W.; Dlakic, W.M.; Engel, R.; Cloninger, M.J. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Highly Cationic Dendrimer Antibiotics. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 3827–3834.

- Fuentes-Paniagua, E.; Sánchez-Nieves, J.; Hernández-Ros, J.M.; Fernández-Ezequiel, A.; Soliveri, J.; Copa-Patiño, J.L.; Gómez, R.; de la Mata, F.J. Structure–Activity Relationship Study of Cationic Carbosilane Dendritic Systems as Antibacterial Agents. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 7022–7033.

- Barrios-Gumiel, A.; Sanchez-Nieves, J.; Pérez-Serrano, J.; Gómez, R.; de la Mata, F.J. PEGylated AgNP Covered with Cationic Carbosilane Dendrons to Enhance Antibacterial and Inhibition of Biofilm Properties. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 569, 118591.

- Heredero-Bermejo, I.; Gómez-Casanova, N.; Quintana, S.; Soliveri, J.; de la Mata, F.J.; Pérez-Serrano, J.; Sánchez-Nieves, J.; Copa-Patiño, J.L. In Vitro Activity of Carbosilane Cationic Dendritic Molecules on Prevention and Treatment of Candida albicans Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 918.

- Gómez-Casanova, N.; Lozano-Cruz, T.; Soliveri, J.; Gomez, R.; Ortega, P.; Copa-Patiño, J.L.; Heredero-Bermejo, I. Eradication of Candida albicans Biofilm Viability: In Vitro Combination Therapy of Cationic Carbosilane Dendrons Derived from 4-Phenylbutyric Acid with AgNO3 and EDTA. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 574.

- Fernandez, J.; Martin-Serrano, Á.; Gómez-Casanova, N.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, S.; Javier de la Mata, F.; Heredero-Bermejo, I.; Ortega, P. Effect of the Combination of Levofloxacin with Cationic Carbosilane Dendron and Peptide in the Prevention and Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms. Polymers 2021, 13, 2127.

- Galdiero, E.; de Alteriis, E.; De Natale, A.; D’Alterio, A.; Siciliano, A.; Guida, M.; Lombardi, L.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, S. Eradication of Candida albicans Persister Cell Biofilm by the Membranotropic Peptide GH625. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5780.