Cancer immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T), have dramatically altered the treatment landscape for many solid and hematologic malignancies. Ongoing research continues to investigate ways to harness the immune system to treat cancer and broaden the indications for currently available therapies. Although immunotherapies have revolutionized the treatment of solid and hematologic malignancies, they have unique toxicity profiles based on their mode of action. Despite this, such innovative therapies can potentially increase already-in-use therapies’ effectiveness.

- FDA

- checkpoint inhibitors

- monoclonal antibody

- CAR-T

- CAR NK

- Trastuzumab

- Enhertu

- PD-1

- PDL-1

1. Cancer Immunity and Immune Evasion

2. Immune Checkpoints

The immune system is continually challenged by exogenous immunogens or endogenous immunogens produced by altered or transformed cells. The immune system’s effector components work continuously to eradicate the causative agents of both endogenous and exogenous immunogens and maintain immunological homeostasis [6][8][9]. A feedback control system termed immune tolerance prevents collateral damage caused by the hyperactivated immune response [10][11][12]. Immune checkpoints are a set of molecular effectors of the immune tolerance system that maintain immune homeostasis and avoid autoimmunity [5][13]. The checkpoint proteins are expressed on the surface of immune cells and help them distinguish between self and non-self by interacting with their cognate ligands [6][9][10][14]. Tumor cells may take advantage of this homeostatic mechanism through the immunoediting process by expressing ligands of immune checkpoints [8][11][14]. These immune checkpoints play a critical role(s) in cancer immunity and have been exploited as major therapeutic targets for cancer immunotherapy (Figure 1A).

2.1. Adaptive Immune Checkpoints

CTLA-4

PD-1

Programmed death protein 1 (PD-1), also called CD279, is an inhibitory receptor expressed on activated T cells. It regulates T cell effector functions in various physiological responses, including chronic infection, cancer, and autoimmunity [19]. The interaction of PD-1 with its ligands PD-L1 (Programmed death ligand 1), also called CD274 and PD-L2 (CD273), mediates PD-1 signaling. [19]. The ligands of PD-1 are typically expressed on antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, B-cells, myeloid cells, and cancer cells [17][20][21]. Studies have shown that PD-1-PDL-1 interaction results in T-cell-mediated immune suppression under normal physiological conditions; however, cancer cells harness this mechanism to evade immune-mediated clearance [8][19]. When PD-1 binds to APCs or cancer cells, it prevents pro-inflammatory processes such as T cell proliferation and cytokine response leading to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [9][11].LAG-3

Lymphocyte activation Gene-3 (LAG-3) is a CD4-related surface receptor present on activated CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and regulatory T cells [22][23]. LAG-3 signaling inhibits T-cell activation, expansion, and cytokine production, leading to exhaustion [24]. It binds to the MHC-II complex and inhibits the interaction of MHC-II with CD4, resulting in reduced TCR signaling and an attenuated immunological response [24]. However, whether MHC-II alone is responsible for the inhibitory activity of LAG-3 is still unclear [25][26]. FLG1, FGL2 (Fibrinogen-like protein 1, 2), LSECtin (Lymph node sinusoidal endothelial cell C-type lectin), Gal3 (Galectin-3), and FREP1 are the other known LAG-3 ligands. The binding of LAG3 to these ligands leads to inhibition of T cell activation [25][26][27]. Studies have shown that LAG-3 is co-expressed on T cells along with other inhibitory molecules such as PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM-3; it promotes greater T-cell exhaustion than LAG-3 alone [28]. In cancer, LAG-3 expressing Tregs accumulate at distinct tumor sites, thereby suppressing cytotoxic T cells. Moreover, LAG-3 expression correlates with poor prognosis in many cancers [29][30]. Blockage of LAG-3 signaling could be used to activate anti-tumor immunity; however, inhibition of the LAG-3 pathway alone has been ineffective [31][32].TIGIT

T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domain (TIGIT) is an Ig superfamily receptor that plays an important role in suppressing innate and adaptive immune responses. [33][34]. It is expressed in several immune cell types, including regulatory T cells, cytotoxic T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and follicular T helper cells [33][34]. TIGIT indirectly lowers T-cell activation, which is crucial for restricting innate and adaptive immunity [33]. The three nectin and NECL molecular family proteins CD155(PVR), CD112(PVRL2 or Nectin-2), and CD113 (Nectin-3), which are expressed on tumor cells or antigen-presenting cells, are the known TIGIT ligands [35][36]. Interaction of TIGIT with its ligands suppresses immune activation [37][38]. The inhibitory effect of TIGIT is compensated by the immune-activating receptor CD226 (DNAM1), also expressed on cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells, and it competes with TIGIT binding to CD155 and CD112 [38][39]. The elevated presence of TIGIT and its cognate ligands results in T cell exhaustion and suppresses DNAM1 signaling culminating in the loss of T cell function [39][40]. Tumor cells exploit the inhibitory TIGIT pathway to escape immune-mediated destruction [33]; therefore, targeting TIGIT could be another strategy for cancer immunotherapy. Multiple TIGIT inhibitors are already in clinical trial stages [33][34][41]. BMS-986207, an anti-TIGIT mAb, is in phase I/II clinical trial for advanced solid tumor as monotherapy and in combination with Nivolumab or Ipilimumab (NCT04570839, NCT02913313). Another phase I/II randomized trial tested the efficacy of anti-TIGIT and anti-LAG3 mAbs in patients with relapsed refractory multiple myeloma either alone or in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone (NCT04150965, NCT02913313).TIM-3

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein-3 (TIM-3), also known as HAVCR2, is an immune checkpoint receptor present on a variety of immune cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, cytotoxic T cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) and [42]. TIM-3 is a type-I membrane protein that acts as a negative regulatory immune checkpoint by suppressing both adaptive and innate immune responses [42][43]. Increased TIM-3 expression on T and NK cells is linked to exhaustion [42]. TIM-3 bind to numerous ligands, some of which include CEA cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1), Galectin-9, phosphatidylserine (PtdSer), and high mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) [44][45][46][47]. Galectin-9, however, is considered the natural ligand of TIM-3 [44]. The co-expression of TIM-3 and CEACAM1 is associated with T cell exhaustion [42][43]. Evidence for TIM-3 as an immune checkpoint in cancer came from preclinical cancer models showing the CD8+ T cells co-express TIM-3 and PD-1. Dual expression of TIM-3 and PD-1 on CD8+ T cells cause more defects in effector function and cytokine production than PD-1 expression alone [48][49]. These findings suggested that TIM-3 may cooperate with PD-1 pathways, resulting in cancer’s dysfunctional phenotype of CD8+ T cells. [48].B7-H3 and B7-H4

The B7 is a transmembrane protein that binds to the CD28 or CTLA-4 and modulates T cell-mediated immune signaling. B7-H3 (CD276) is expressed on various immune cells, including T cells, B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and natural killer (NK) cells [50][51]. Whereas B7-H4 is ubiquitously expressed in immune cells, however, its robust expression is primarily rescrticted to activated T cells B-cells and monocytes and dendritic cells [52]. Both B7-H3 and B7-H4 are over-expressed in several solid and hematologic malignancies, and their expression is associated with poor prognosis in many cancers, including renal cell carcinoma (RCC), colorectal cancer (CRC), and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [50][51][52].VISTA

V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA) is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein, also known as B7-H5, Dies1, PD-1H, Gi24, encoded by VSIR gene in humans [53]. It is mainly expressed on dendritic cells, macrophages, and myeloid cells, while its expression is relatively low in CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and Treg cells [53][54]. VISTA has characteristics with the B7 and CD28 family proteins and may function as a ligand and a receptor [55][56]. The known ligands of VISTA are P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1) and V-set and Ig domain-containing 3 (VSIG3). The binding of VISTA to PSGL-1 is known to occur at an acidic pH, such as in the tumor microenvironment (TME); however, at physiological pH, VISTA-expressing cells can bind to PSGL-1. Interactions of VISTA with its ligands lead to attenuation of T cell function. [57][58]. VISTA is a key negative immune checkpoint regulator, which locks T cells in a quiescent state. It has been shown to inhibit T cell responses in vitro and in preclinical models of autoimmunity and cancer [59][60][61]. The role of VISTA as an immune checkpoint is demonstrated in studies using VISTA knockout (Vsir−/−) mice that exhibit exacerbated T cell responses and develop spontaneous autoimmunity [62]. The preclinical studies using several mouse models have demonstrated that VISTA inhibition leads to an increased T cell infiltration, proliferation, and effector activity in the tumor microenvironment [61]. The immunosuppressive role of VISTA on both lymphocytes and myeloid cells, as well as the its widespread expression on TILs, indicate that VISTA-blockade approaches may have broad therapeutic significance [54][57]. Three mAbs, VSTB112, P1-068767 (BMS-767), and SG7 targeting VISTA are in developmental phases. These antagonistic mAbs inhibit VISTA interaction with human PSGL-1 and VSIG3 with comparable potency [63].OX40/OX40L

The OX40 receptor (CD134) is a membrane-bound glycoprotein that belongs to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily. Its interaction with the OX40 ligand (a type II transmembrane protein) expressed on B cells, DCs, and endothelial cells, play a critical role in activating the effector function of CD4+ T-helper cells [64][65]. OX40 and CD28 signals have strong synergistic effects on the survival and proliferation of CD4+ T cells [66]. OX40L interaction with its receptor OX40 increases the expansion and survival of naive CD4+ T cells and memory Th cells by inhibiting peripheral deletion [67][68][69]. OX40-OX40L interaction plays a crucial role in T cell activation and improves T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity, resulting in tumor regression and increased survival [70]. OX40 agonist antibodies have shown promising results in preclinical cancer models, including lung, colon, and breast cancer, as well as murine breast (4T1) and melanoma (B16) cancer models [70][71]. There are several ongoing clinical trials of OXO40 agonists, notably MEDI0562, a humanized OX40 agonist mAb is in phase I clinical trials for advanced solid tumors (NCT02318394). Anti-OX40 mAb, MEDI6469 as neoadjuvant therapy, is being investigated for advanced solid tumors in phase I as monotherapy and for B- cell lymphomas in phase II, in combination with other immunotherapeutic monoclonal antibodies (Tremelimumab, Durvalumab, and Rituximab) (NCT02205333). Neoadjuvant therapy is defined as the administration of therapeutic agents before the start of the main treatment [68].A2A/B-R and CD73

In immune cells, CD73 (cluster of differentiation 73) dephosphorylates and transforms extracellular AMP to adenosine, which mediates its effects through the binding with the A2A or A2B adenosine receptor (A2AR or A2BR), which are expressed on T cells, APCs, NK cells, and neutrophils [72]. In the tumor microenvironment, high levels of ATP produced due to tissue destruction, hypoxia, and inflammation are catabolized by CD73, which is overexpressed in multiple immune cells present in the tumor environment as well as in multiple cancers [73][74].NKG2A

Natural killer group protein 2A (NKG2A) is expressed on circulating NK cells and certain T cells and is enhanced in chronic inflammatory conditions [75]. NKG2A dimerizes with CD94 after interacting with its ligand HLA-E, inhibiting NK and T cell activity [75]. Elevated NKG2 expression has been linked to poor survival in ovarian and colon malignancies [66][67][68][69]. In the presence of other immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-1 or anti-PDL-1, blocking NKG2A was shown to enhance the anti-tumor response by T and NK cells [76][77][78]. Monalizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets NKG2A, has been evaluated as monotherapy in phase II clinical trials for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [76][77][78].2.2. Innate Immune Checkpoints

SIRPα-CD47

IgSF family member SIRPα is a glycosylated transmembrane mostly expressed on macrophages, dendritic cells, and granulocytes [79][80]. However, except for T cells, it is expressed in several additional cell types of hematopoietic origin [80][81]. The primary SIRPα ligand is CD47 [79][81][82][83]. Upon binding to CD47, SIRPα is phosphorylated at its intracellular C-terminal ITIM motifs and triggers anti-inflammatory signaling in phagocytes [81][82][84]. This phosphorylation of SIRPα activates cytoplasmic phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2, which subsequently dephosphorylate Paxillin and non-muscle Myosin IIA, resulting in reduced phagocytosis [79][81][82][83]. Inhibition of SIRPα-CD47 interaction by anti-CD47 or anti-SIRPα antibody leads to a significant increase in cancer cell phagocytosis by macrophages and a decrease in tumor burden [81][82][83]. Even though normal human cells (including hematopoietic cells) frequently express CD47, blockade of CD47 or SIRPα preferentially causes phagocytosis of tumors because normal human cells lack prophagocytic or “eat me” signals [9].LILRB1/MHC-I and LILRB2/MHC-I

Leukocyte Ig-like receptor B1 (LILRB1) is expressed in both innate and adaptive immunity cells, including macrophages, granulocytes such as eosinophils and basophils, dendritic cells, a subset of NK cells, as well as certain T and B cells [85]. Whereas MHC-I is expressed on nucleated cells and presents the processed antigen to the CD8+ T cells. Interaction of MHC-I to the T cell receptor is followed by a cascade of events leading to the activation of the cytotoxic function of CD8+T cells [32][85][86]. MHC-I is a heterodimer molecule made up of a heavy -chain and a β2-microglobulin (β2M) chain [86]. The expression of MHCI on cancer cells has recently been correlated with the resistance to phagocytosis through the interaction of its β2-microglobulin chain with LILRB1 receptors expressed on phagocytes [9][85][86]. However, it is worth noting that LILRB1 only interacts with MHCI via the β2M chain, as opposed to MHC-TCR, interacts which requires an intact MHC molecule [9]. Therefore, the approaches that precisely disrupt the LILRB1-β2M interaction can be potent innate immune targeting strategies [86].Siglec10-CD24

Sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 10 (Siglec10), is predominantly expressed on innate immune cells such as macrophages [87][88], dendritic cells [89], and NK cells [90]. It acts as an innate immune checkpoint by interacting with its ligand CD24 present on tumor cells, leading to the functional inactivation of immune cells [87][91]. Multiple tumors have been shown to have altered Siglec10 expression [87], and an elevated expression in patients with kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC) negatively correlates with the survival of patients [87].APMAP

Adipocyte plasma membrane-associated protein (APMAP) is another novel antiphagocytic protein that has recently been discovered in a genome-wide CRISPR knockout screen for the identification of regulators of antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) [92]. The study showed that the genetic depletion of APMAP in lymphoma cells significantly accelerates antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis by human macrophages [92]. Furthermore, a counter CRISPR-knockout screen in J774 murine macrophage cells identified GPR84 (probable G-protein receptor) as a possible APMAP receptor on the macrophages [92].2.3. Limitations and Challenges of ICI Therapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been employed as immunotherapeutic agents in treating various malignancies [93]. Immunotherapy has the potential to elicit long-lasting responses in a subset of patients with advanced diseases that can be maintained for several years after treatment cessation [94]. Compared to chemotherapy or targeted therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy exhibits various tumor response patterns, such as delayed response, durable response, dissociated pseudoprogression, and hyperprogression [95]. One of the limitations of ICI therapies is the lack of reliable predictive biomarkers of durable response and limited understanding of clinically relevant determinants of pseudo or hyper progression. No standard definition of durable responses to ICI-based therapies has been devised, and optimal treatment duration in case of durable response has not been established [94][95].

ICIs have shown remarkable success in inducing durable responses in several patients with malignant disease; however, these therapies confer distinct toxicities, depending on the type of therapy used [96]. Although acute toxicities are more frequent, chronic immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which happen in some patients, are becoming more recognized [96]. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are a distinct range of adverse effects of ICI therapies that resemble autoimmune reactions [97]. Clinical trial data analysis indicates that irAEs are estimated to occur in a significant proportion of cancer patients undergoing ICI therapies [98]. Since irAEs often result from immune system hyperactivation, this suggests that the exhausted immune cells have been reinvigorated to attack both tumor and the normal cells [96][97].

Another limitation of ICI-based therapies is primary and acquired resistance. Although immune checkpoint therapy has been shown to have persistent response rates, many patients do not benefit from it, often called primary resistance. However, some responders experience a relapse of the metastatic disease after their initial response, also known as acquired resistance. Such types of heterogeneous responses have been observed in various metastatic lesions, even within the same patient [99]. This resistance is influenced by both extrinsic tumor microenvironmental variables and tumor intrinsic factors. The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment created due to the presence of Tregs, M2 macrophages, MDSCs, and other inhibitory immune checkpoints largely contribute to acquired resistance [100]. Tumor resistance is also influenced by the absence of tumor antigen, loss or downregulation of MHC-I, alterations in the antigen-presentation, and inadequate immune cell infiltration. [99][101].

3. Adoptive Cell Therapy

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) is another fast-emerging field of cancer immunotherapy in which a patient’s cells are genetically engineered ex-vivo and then transferred back to the patient’s body as therapeutic agents. T cell based adoptive cell therapies such as TILs (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes), Synthetic TCRs (engineered T-cell receptors) and CAR T (chimeric antigen receptor T cells) and NK cells based therapies called CAR-NK have been developed.

3.1. TILs (Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes)

TIL therapy is an adoptive cell therapy that utilizes the patient’s naturally occurring T-lymphocytes infiltrating the tumor microenvironment [102][103]. The fundamental idea behind tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy is that while cytotoxic T cells that infiltrate the tumor microenvironment are exposed to tumor antigens and can attack tumor cells, they cannot completely eradicate the tumor because of their insufficient numbers [102][103][104]. In TIL therapy, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are isolated from the resected tumors, expanded ex vivo under activating conditions, and then reinfused into the patients to achieve a therapeutic anti-tumor response [102][103][105][106] (Figure 2A).

3.2. TCR (T Cell Receptor) Therapy

TCR-based adoptive cellular therapy uses genetically manipulated lymphocytes that are targeted against specific tumor antigens. This approach utilizes the ability of TCRs to recognize the tumor-specific antigens presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) present on the surface of malignant cells [107][108][109]. Typically, TCR-based therapy requires methodical and well-coordinated steps that include patient’s HLA (human leukocyte antigen) typing, selection of tumor-specific antigen, leukapheresis, manufacturing of transduced TCR product, lymphodepletion, and delivery to the patient [107][108][109] (Figure 2A). Most cell-based immunotherapies face challenges in delivering an effective pool of anti-tumor effector cells. However, the ex vivo production of up to billions of activated lymphocytes with known antigen selectivity and potency allows TCR therapy to overcome this obstacle [107][109]. TCR-based therapy utilizes a variety of immune cells, but T cells and NK cells are used most frequently [107]. Selecting a target-specific antigen (TSA) is the fundamental step in developing TCR-T cells. A specific antigen must be overexpressed on cancer cells compared to normal cells to prevent off-target and detrimental effects on healthy tissues. NY-ESO-1 (New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma-1), which belongs to the cancer/testis (CT) antigens category, has been the target of most TCR-based therapy clinical trials to date, accounting for more than 35% of TCR product based clinical trials. CT antigens are a category of tumor antigens whose normal expression is restricted to male germ cells in the testis but not in adult somatic tissues [110]. In cancers, expression of CT antigen is elevated in a significant percentage of tumors of various types [110][111]. Other TSAs considered in TCR therapy include mutant antigens and neoantigens, most of which are safe targets due to their exclusive expression in tumor cells. TCR-engineered autologous T-cell therapy has demonstrated significant preclinical response in multiple myeloma [112], melanoma [113], and other solid tumors [114][115][116].3.3. CAR T Cells

CAR (Chimeric antigen receptor) T cells are modified primary human T cells engineered to express a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) capable of recognizing tumor-specific antigens expressed on the surface of tumor cells [88][89][90]. CAR T-cell therapy has shown unprecedented growth in recent years and has become the most promising immunotherapy for B-cell-related malignancies [117][118][119]. The development of a chimeric antigen receptor CAR T cell therapy starts with collecting a patient’s blood and separating lymphocytes using a technique called apheresis or leukapheresis [120]. The apheresis product is then processed to remove undesirable cell types that could interfere with T-cell activation and proliferation [121]. The CAR gene constructs expressing a specific antigen are subsequently introduced into T cells through one of the numerous techniques discussed elsewhere [122][123]. Eventually, the CAR T cells are amplified ex vivo to generate an adequate number of cells for the therapeutic dose. When CAR T cells are re-introduced into the patient, the receptors assist the T cells in recognizing cancer cell antigens and the destruction of cancer cells (Figure 2B).3.4. CAR-NK Cell

In the field of cell-based immunotherapies, CAR NK cells have attracted significant attention, like CAR T cells [124]. CAR NK cells have several advantages over CAR T cells, such as antigen-independent spontaneous cytotoxicity, differentiated cytokine secretion, and better survival in vivo [124][125]. Engineered primary human NK cells and NK-92 cells expressing CAR targeted against CD19, CD20, CD244, and HER2 have been studied in a wide range of preclinical settings. Natural killer (NK) cell therapy, CYNK-001, produced from cryopreserved human placental hematopoietic stem cells, recently received fast-track designation from the U.S. FDA for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [126]. A phase I/II trial of CD19-targeted CAR-NK treatment obtained from cord blood is now underway in patients with relapsed or refractory CD19+ malignancies (NCT03056339). Having established success in hematological malignancies, many NK cell-based therapies are currently in clinical trials for solid tumors [127][128][129]. Further advancement in NK cell therapy is NK-cell engagers, which aid in the identification of target cells as well as NK cell activation. This approach is called ANKET—antibody-based NK-cell engager therapy [130][131][132]. The first generation ANKETs are antibody-like molecules that target two NK cell activation receptors, CD16 and NKp46a, as well as a tumor-specific antigen. When these engager antibodies bind to NK cell receptors, they connect NK cells to target tumor cells and activate the NK cell’s effector function [127][130]. The first ANKET therapy, SAR443579, which targets the tumor antigen CD123 [133], is currently being tested in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (R/R AML), B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), or high-risk myelodysplasia (HR-MDS) (NCT05086315).3.5. Limitations and Challenges of CAR T Therapy

CAR T cell therapy has several limitations, which include antigen escape, antigen heterogeneity, trafficking of CAR T cells and tumor infiltration, immunosuppressive microenvironment, and CAR-T cell-associated toxicities [134]. One of the most challenging limitations of CAR-T cell therapy is the emergence of tumor resistance to single antigen targeting CAR constructs. Despite the ability of single antigen CAR-T cells to induce a potent response, some malignant cells in patients can exhibit a partial or complete loss of target antigen expression. This mechanism is known as antigen escape [134][135]. Recent follow-up data from relapsed and/or refractory ALL patients and multiple myeloma treated with CD19 CAR-T therapy or B-cell maturation antigens (BCMA) targeted CAR-T cells indicates that the incidence of resistance to therapy in a small percentage of patients is due to the loss of CD19 and BCMA [134][135][136][137][138]. Although CAR-T therapies have shown great potential in treating hematological cancers, their efficacy remains undetermined in solid tumors. Targeting solid tumor antigens is challenging since many of these antigens are often expressed to varying extents by normal tissues. Antigen selection is, therefore, critical for CAR-T cell design to enhance therapeutic effectiveness and reduce off-target effects. [134].

The efficacious therapeutic response of CAR- T therapy is determined by the extent of CAR-T cell activation and cytokine secretion after engaging with the target antigen. The CAR-T cell activation is largely influenced by factors such as the level of tumor antigen, tumor burden, the affinity of the antigen binding domain to its target epitope, and the CAR’s costimulatory elements [139][140]. Future modified approaches may include refining CAR components, their modular structure, and activation kinetics to optimize therapeutic potential and reduce toxicity. Another potential strategy for reducing CAR-T cell-mediated toxicity would be to incorporate bimodal “off-switches” that would allow modified cells to be selectively deactivated at the onset of adverse events [134][139][140]. Strategies using tandem CARs or dual CARs that simultaneously recognize two or more different tumor antigens in a single design with two scFvs have reduced the relapse rate in CAR T treatments [141]. Preliminary findings from clinical trials involving dual-targeted CAR-T cells have been promising [142]. Given the potential of adoptive cell therapies to translate into effective anticancer treatment, further advancements in the field will lead to more promising and reliable tools.4. Monoclonal Antibodies

A potential class of targeted anticancer therapeutics with a variety of mechanism(s) of action are monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) [143][144][145][146]. The U.S. FDA has approved more than 100 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to treat a variety of human disorders, including cancer and autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases [147][148]. Since the successful applications of immunoglobulin G (IgG) mAbs, there have been significant advances in antibody engineering technology that led to the development of newer and more efficacious antibody formats and derivatives such as antibody fragments, non-IgG scaffold proteins, bispecific antibodies (BsAbs), antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), antibody-radio conjugates, and immunocytokines that have successively been used as alternative therapeutic agents for a broad range of cancers [143][144][145][146][149][150]. Monoclonal antibodies attack cancer cells in various ways (Figure 3A), including directly targeted killing, immune-mediated destruction, blocking immune checkpoints, preventing blood vessel formation, and delivering a cytotoxic drug to cancer cells [143][144][145][146][149][150].

4.1. Direct Killing and Immune-Mediated Killing

MAbs, upon antigen-specific binding to tumor-associated antigens, induce cytotoxic effects either by neutralizing or killing through cell-intrinsic proapoptotic signaling mechanisms [143][146][148]. One example is Trastuzumab, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody that inhibits cancer cell growth by interfering with HER2 dimerization and intracellular signaling [143][144]. The immune-mediated mechanism involves antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP).

4.2. mAbs Targeting Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, or the formation of new blood vessels, is vital for tumor growth and progression [151]. Inhibiting angiogenesis has long been seen as a promising avenue for the generation of new, effective, and targeted cancer treatments capable of inhibiting tumor growth and spread [151][152][153]. The use of monoclonal antibodies that target the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway has significantly improved cancer treatment [153].4.3. Antibody-Drug Conjugates

ADCs are the most rapidly emerging monoclonal antibody-based cancer immunotherapy field, with significantly greater potency than naked antibodies [154][155]. This strategy employs a mAb attached to the cytotoxic payload via a chemical linker directed to a target cell surface antigen expressed on the cancer cells [156][157][158]. Typically, ADC contains three components: the monoclonal antibody (mAb), the linker, and the cytotoxic or cytostatic/cytotoxic drug. The mAb is an essential component of ADC that dictates specificity to the tumor cell, by binding to tumor antigens, acts as a precise carrier to transport the cytotoxic agents to the target cell without harming healthy cells that do not express the target antigen [154][155][157][158][159][160]. The second component of ADC is a linker. a chemical entity that links the mAb to the cytotoxic drug [159][161][162]. The two types of linkers are used based on the drug release mechanisms, (1) Cleavable linkers; that are cleaved in the presence of low lysosomal pH or certain enzymes found in different cellular compartments; cytotoxic substances are released, (2) non-cleavable linkers, on the other hand, require ADC proteolysis to release the active cytotoxic agent [159][161][162][163]. The cytotoxic agent is the third important component of ADC also known as ‘payload,’ which typically is a cytotoxic drug such as microtubule-disrupting agents (maytansinoids, auristatin analogs, and tubulysins) or DNA-damaging agents (duocarmycins, calicheamicins, and pyrrolo-benzodiazepines) [158][162][163][164].4.4. Antibody Radioimmunoconjugate (RIC)

A monoclonal antibody (mAb) coupled to a radionuclide is called radioimmunoconjugate [165][166], RICs. Unlike ADCs, they do not require cellular uptake or endocytosis to provide anti-cancer activity; instead, DNA strand breaks occur in the target cell when a mAb emitting radionuclide attaches to its targeted antigen [165][166][167]. The advantage of radioimmunotherapy (RIT) over standard radiotherapy is that it is less hazardous and improves the efficacy of mAbs [165]. Radio-immunoconjugates (RICs) have been successfully developed as theragnostic tools, with the FDA approving Ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®; Biogen Idec) and 131I-tositumomab radioimmunoconjugate for the treatment of non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ibritumomab tiuxetan is a yttrium-90, and Tositumomab is an iodine-131 radionuclide coupled monoclonal antibody that targets the CD20 antigen on B-cell malignancies [165][166][167][168][169].4.5. Bispecific Antibodies

Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs), a complex family of antibodies, can bind two distinct antigens epitopes [170]. Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) have received a lot of interest as a new generation approach of monoclonal antibody-target cancer immunotherapy that focuses on engaging immune cells with cancer cells or concurrently targeting two receptors [170][171][172]. Bispecific T cell engagers (BiTEs) are essentially bispecific antibodies with two variable fragments of single-chain antibodies. One of the bispecific antibodies targets a cell surface molecule on T cells, such as CD3, while the other specifically targets the surface antigens on tumor cells. The immunological synapse created by contacts between immune cells and tumor cells via BiTEs results in the production of effector cytokines and the killing of the tumor cell [170][171][172][173].5. Cytokine Therapies

Cytokines are immune system components that play an important role in the cancer immunity cycle; however, the expression and activity of many cytokines are dysregulated in malignancies [174][175][176]. The first cytokine to be used in the treatment of cancer was IL-2. It is considered not only the first cytokine therapy but also the first reproducible and effective human cancer immunotherapy [177]. The U.S. FDA approved IL-2 in 1992 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and in 1998, subsequently, it was later approved for metastatic melanoma [178]. Though high-dose IL-2 monotherapy demonstrated encouraging outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, its use remained limited due to toxicity and high production costs [177][178]. Another challenge with IL-2 is that it can activate both cancer-killing effector T cells as well as immunosuppressive regulatory T cells. Therefore, further research is required to better understand the complex biology of IL-2 to harness its utility as cancer immunotherapy. One of the fundamental limitations of cytokine therapy is the pleiotropic effect of cytokines [174][179]. Each cytokine can affect numerous cell types that elicit both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses [174][180]. The expensive cost of manufacture, the need for producing clinically required doses to elicit a reliable immunological response, as well as the short half-life and systemic toxicity, are further barriers to the effectiveness of cytokine therapy [174][180][181].

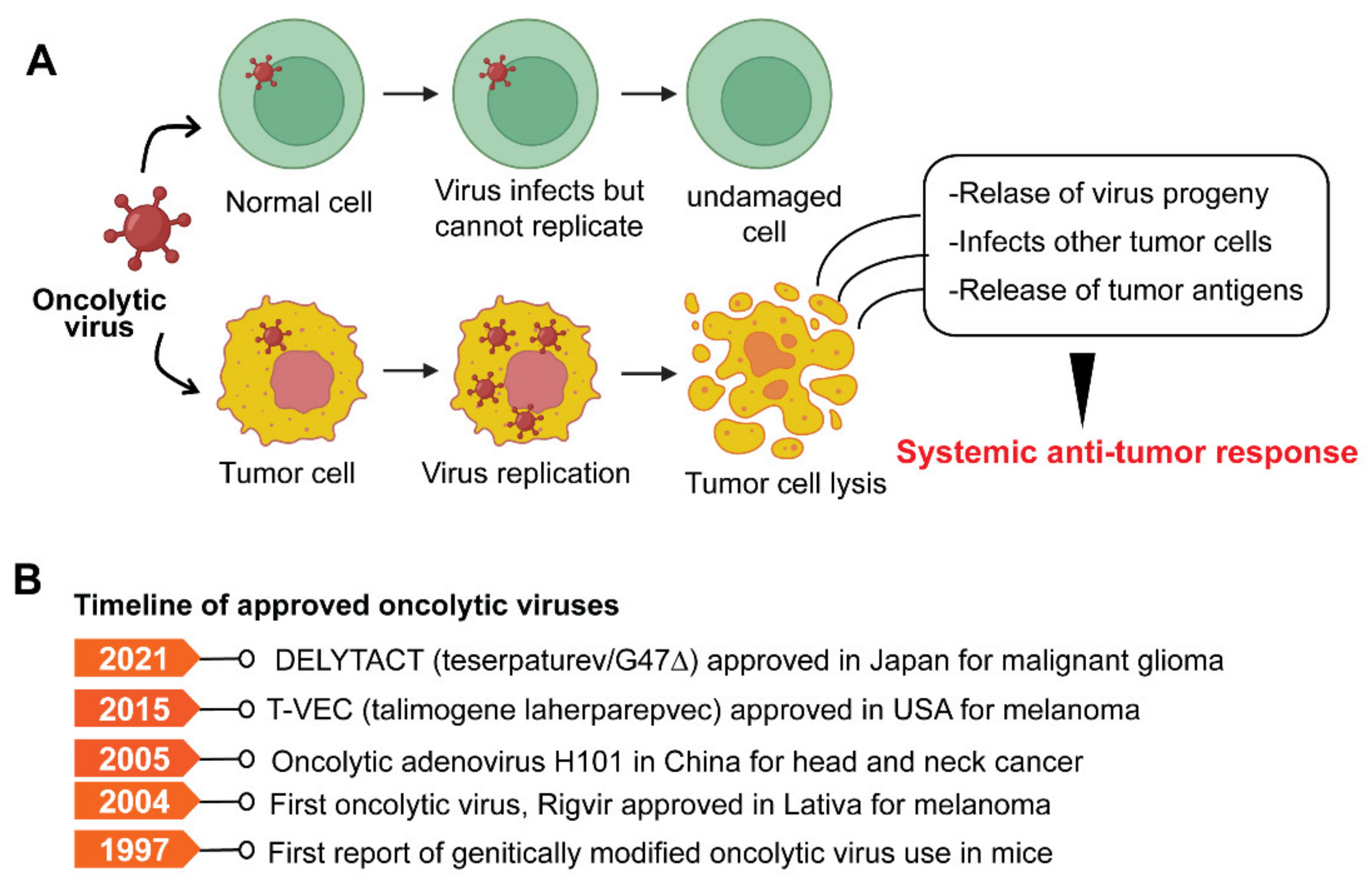

6. Oncolytic Viruses

Oncolytic viruses (OVs) are genetically modified viruses that lack virulence but can still attack and kill cancer cells without harming healthy cells [182]. OVs are a unique class of therapeutic agents that exhibit broad-spectrum activity to induce tumor cell death and enhance both innate and tumor-specific adaptive immune responses [182][183]. Oncolytic viruses can kill cancer cells in various ways, including direct virus-mediated cytotoxicity and cytotoxic immune effector mechanisms [182]. A model depicting typical OV and its mode of action is shown in Figure 4A.

7. Cancer Vaccines

Cancer vaccines stimulate the immune system to mount an antitumoral response and protect against cancer [93][185]. Cancer vaccines are typically classified as either prophylactic or preventative or therapeutic. Prophylactic vaccines protect against oncogenic virus infection. Therapeutic vaccinations, on the other hand, harness the potential of the immune system to eradicate neoplastic cells. [185][186]. Therapeutic cancer vaccines involve the exogenous administration of specific tumor antigens to the patient to activate their adaptive immune system and elicit an anti-tumor response [185] (Figure 5).