The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Animal Rule was devised to facilitate approval of candidate vaccines and therapeutics using animal survival data when human efficacy studies are not practical or ethical. This regulatory pathway is critical for candidates against pathogens with high case fatality rates that prohibit human challenge trials, as well as candidates with low and sporadic incidences of outbreaks that make human field trials difficult. Important components of a vaccine development plan for Animal Rule licensure are the identification of an immune correlate of protection and immunobridging to humans. The relationship of vaccine-induced immune responses to survival after vaccination and challenge must be established in validated animal models and then used to infer predictive vaccine efficacy in humans via immunobridging.

- immune correlate

- immunobridging

- Animal Rule

- ELISA

- PsVNA

- binding

- neutralization

- animal model

- vaccine

- filovirus

1. Introduction

- “There is a reasonably well-understood pathophysiological mechanism of the toxicity of the substance and its prevention or substantial reduction by the product;

- The effect is demonstrated in more than one animal species expected to react with a response predictive for humans, unless the effect is demonstrated in a single animal species that represents a sufficiently well-characterized animal model for predicting the response in humans;

- The animal study endpoint is clearly related to the desired benefit in humans, generally the enhancement of survival or prevention of major morbidity; and

- The data or information on the kinetics and pharmacodynamics of the product or other relevant data or information, in animals and humans, allows selection of an effective dose in humans” [1] (Sec. 314.610). (In the case of vaccines, immune responses are the relevant parameter, as pharmacodynamics and kinetics are not applicable) [7].

-

“There is a reasonably well-understood pathophysiological mechanism of the toxicity of the substance and its prevention or substantial reduction by the product;

-

The effect is demonstrated in more than one animal species expected to react with a response predictive for humans, unless the effect is demonstrated in a single animal species that represents a sufficiently well-characterized animal model for predicting the response in humans;

-

The animal study endpoint is clearly related to the desired benefit in humans, generally the enhancement of survival or prevention of major morbidity; and

-

The data or information on the kinetics and pharmacodynamics of the product or other relevant data or information, in animals and humans, allows selection of an effective dose in humans” [1] (Sec. 314.610). (In the case of vaccines, immune responses are the relevant parameter, as pharmacodynamics and kinetics are not applicable) [7].

2. Animal Models and Immune Correlates of Protection

The foundation of an effective immunobridging strategy begins with selection of the appropriate animal model(s) and the immune correlate(s) of protection (which is established in the animal model via efficacy studies). The immune correlates discussed here are defined as immunological markers that correlate with protection and are either mechanistic (i.e., causally related to protection) or non-mechanistic (not causally related to protection) in nature. The first step in identifying an immune correlate of protection is to identify an animal model that reasonably predicts human pathogenesis and immune responses, and infection conditions that allow breakthrough in vaccine protection. Two animal models/species may be required according to Animal Rule guidelines if there is no single animal model that represents a sufficiently well-characterized animal model for recapitulating human disease, and the selected animal model(s) must be agreed upon by the FDA [1]. Animal model selection is so critical that three of the four Animal Rule criteria (criteria 2–4, described in SectionSection 1 1 above) stipulate requirements of the animal model(s); the more similar the pathophysiology between animal and human, the more relevant to humans the immune correlate of protection defined in the animal model is considered to be [1]. There are numerous filoviral animal models of disease available with varying levels of relevance to human pathophysiology. Mouse, guinea pig and hamster models are cost-effective, but they have not been considered suitable models for Animal Rule licensure, in part due to the need for challenge virus adaptation and/or genetic attenuation of the immune system to yield severe disease [29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. In other words, efficacy against the human wild-type virus for which the candidate vaccine is ultimately intended cannot be directly evaluated in these models. Ferrets, in contrast, display more faithful mimicry of the pathophysiology of human disease (for example, EBOV and SUDV) compared to rodents without virus adaptation. Unfortunately, commercially available ferret-specific immune reagents are somewhat limited, and ferrets are not susceptible to MARV infection, complicating vaccine development and evaluation of multivalent vaccines [37][38][38,39]. For filoviruses such as EBOV, MARV and SUDV, nonhuman primates (NHPs) are considered the gold standard for evaluation of vaccine and therapeutic efficacy; rhesus and cynomolgus macaques are used most commonly [39][40][40,41]. When comparing filovirus disease between NHPs and humans, the constellation of clinical signs and the pathophysiology are similar [15][16][37][39][41][42][43][44][15,16,38,40,42,43,44,45]. No other filovirus animal model faithfully mimics human disease pathophysiology as well as NHPs [37][39][42][43][38,40,43,44]. This is not surprising given the genomic homology between NHPs and humans [45][46][46,47]. For instance, dysregulation of coagulation pathways, a key hallmark of human filovirus infection/pathogenesis, is observed in NHP models, but only a subset of these coagulopathies is present in mice [37][42][47][38,43,48]. Still, NHPs do not perfectly mimic human disease. The progression of filoviral disease in fatal NHP models is accelerated compared to the kinetics in humans, the entire disease course being up to about 13 days (depending on the filovirus, the animal species/model and other factors) compared to an incubation period in humans of up to 21 days (although the exact number of days is likely dependent on the factors discussed in the section above) [17][42][43][17,43,44]. Additionally, NHP filoviral models for EBOV, MARV and SUDV use a virus challenge dose and route that are nearly uniformly lethal, whereas human case fatality rates average roughly half that for most filoviruses (MARV, 24–88%; EBOV, 25–90%) [15][16][37][48][49][50][51][52][53][15,16,38,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Importantly, while there is a difference in lethality between humans and NHPs, ERVEBO showed 100% survival in NHPs, and that predicted high-level protection in a human efficacy trial [25][54][55][25,55,56]. High lethality in the NHP challenge does yield a stringent test of vaccine efficacy. Likewise, the intramuscular injection virus exposure route in NHPs aims for uniformity in the high dose exposure and has relevance to human needlesticks that resulted in fatalities [56][57][57,58]. Following identification of an animal model(s) for evaluation of a vaccine using the Animal Rule, an immune correlate(s) of protection must be identified where the immune correlate should be predictive of the desired study endpoint such as viral load or survival [1]. Correlates of protection may vary depending on the vaccine platform, antigen, its route of administration, virus species and the animal model [7][58][7,59]. Clinical trials must be done to confirm that the defined NHP immune correlate is assayable in humans and in the selected animal species/model in the same assay format; these correlates are not necessarily related to the mechanism of protection [1][7][58][1,7,59]. Immune correlates of survival associated with natural immunity may differ from those of vaccine-derived immune correlates of protection [7][59][7,60]. For some pathogens, defining the immune correlate of protection is relatively straightforward. For instance, protection against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been shown to significantly correlate with neutralizing antibody titers, and toxin-neutralizing antibodies (TNA) are strongly predictive of survival against anthrax [60][61][62][63][64][61,62,63,64,65]. Importantly, these correlates need to be confirmed through properly designed animal studies and validated immunoassays. Not every pathogen will have such clearly defined correlates of protection against disease. Vaccine-induced (and natural) protection against filovirus infection appears to be multifactorial and linked to both T cell (especially CD8+) responses and anti-filovirus GP immunoglobulin G and M (IgG and IgM, respectively) serum antibody responses [7][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][7,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. While T cells play a mechanistic (causal) role in protection for a GP-based vaccine against Ebola virus, a statistically significant GP-specific T-cell correlate of protection is more difficult to define, due in part to the dynamic nature of T-cell responses [66][67]. For the same vaccine, passive transfer of vaccine-induced IgG failed to provide complete protection against filovirus infection in NHPs, suggesting that antibodies may not play a mechanistic role in protection [66][67]. In contrast, protection conferred by another GP-based vaccine, also against Ebola virus, but on a different platform, seems to be more dependent on antibodies, as CD4+ depletion in NHPs abrogated GP-specific antibody production and animals succumbed to virus challenge [68][69]. To date, there are no data to definitively support GP-specific antibodies as mechanistic correlate. Nonetheless, vaccine-induced antibodies do correlate with macaque survival in several studies [2][26][2,26], and studies indicate that anti-GP IgG correlates with human survival for ERVEBO [74][75]. Notably, passively infused GP-directed monoclonal and polyclonal antibody therapeutics have been shown to confer protection in both macaques and humans, thus demonstrating the biological relevance of the immune correlate [24][75][76][24,76,77]. The varied outcomes in these studies draw attention to the difference between correlation and causation with respect to the role of antibodies in protection against filoviral disease and emphasize the case-by-case (model-dependent) ascribed role of antibodies. Nearly as important as biological relevance in the selection of an immune correlate of protection are practical considerations. For example, T-cell assays appropriate to assess cellular immunity in a preclinical setting have been established; however, these assays can be difficult to implement and validate for clinical trials as they require more complex procedures than those used for antibody assessment. Additionally, T-cell responses are dynamic and transient [77][78]; capturing them to define a precise quantitative correlate of protection is difficult when compared to IgG antibodies, which are more stable and longer lasting. Not only are anti-filovirus serum GP IgG antibody levels easier to capture, but they are also comparatively easy to assess in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Although total binding antibody titers (as assessed by ELISA) are not necessarily mechanistic correlates, they correlate well with protection in at least some studies [2][26][2,26]. Neutralizing antibody titers, such as those defined by plaque reduction neutralization assays and pseudovirus neutralization assays, have been shown to correlate with protection against mortality and have been identified in human filovirus disease survivors [2][78][79][80][2,79,80,81]. Neutralization assays, however, are more complicated (using live virus) than ELISAs and are less predictive of survival in some filovirus challenge studies [73][81][74,82]. Total serum binding anti-filovirus GP IgG titers are good overall correlates of protection (as defined in NHPs), both biologically and practically, due to the strength of correlation and the relative simplicity of measurement [2][7][26][82][2,7,26,83]. Such careful consideration given to selecting an immune correlate(s) of protection presupposes that the bioassay used to measure the correlation must be validated, robust and feasible in the clinic and the laboratory. Concurrence with the FDA on the immune correlate of protection to be evaluated during vaccine development is critical, since the immune correlate serves as the basis for inferring predictive human efficacy from animal immunogenicity and survival data. For further reading, filovirus immune correlates have been well reviewed elsewhere [7][58][71][83][7,59,72,84].3. Overview of Immunobridging

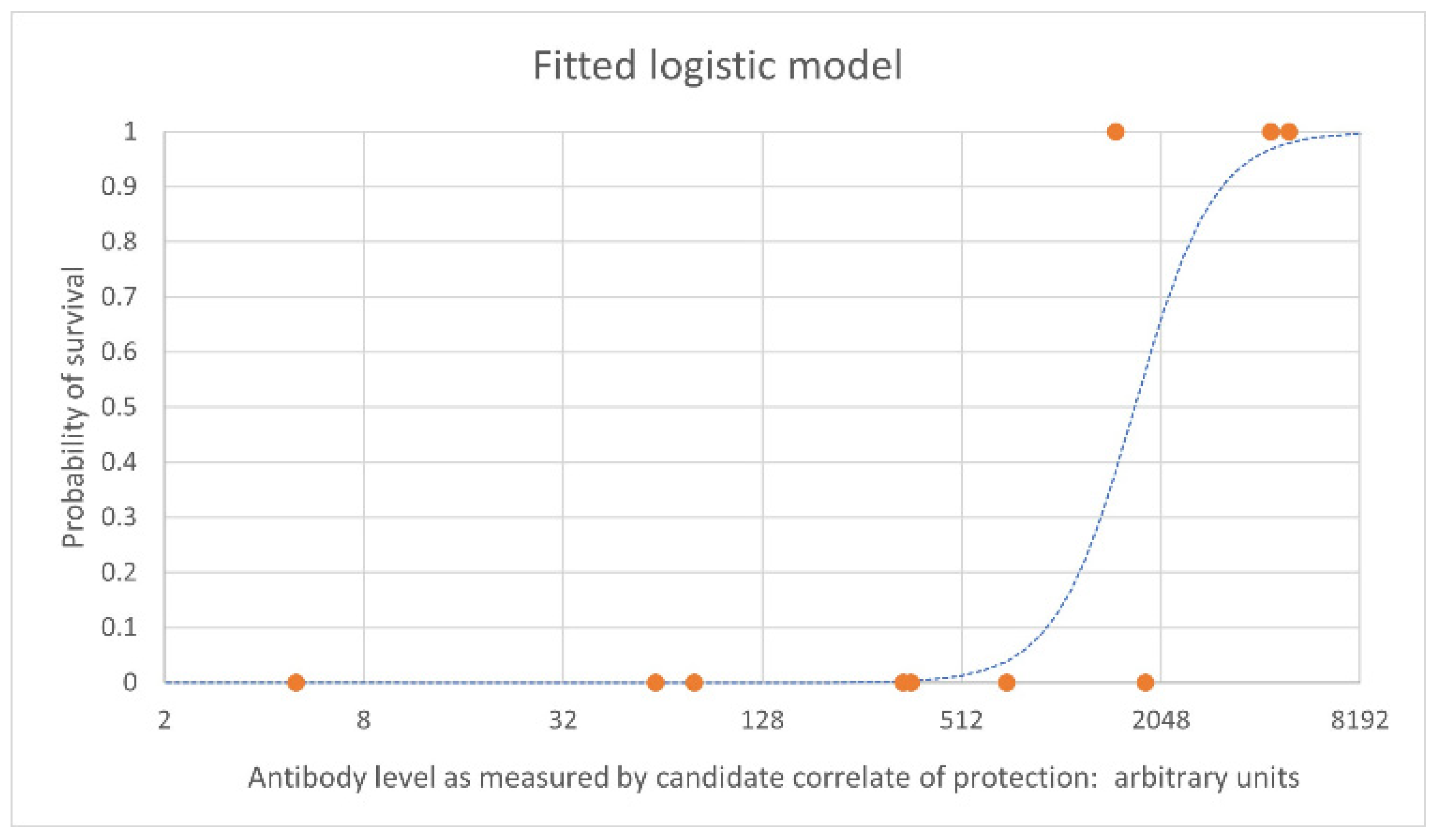

Immunobridging is the process by which human vaccine efficacy is inferred based on animal immunogenicity and survival data. The immune correlate of protection should be assessed in humans and animals using the same assay. The first step in the process is to define a statistically significant relationship between the candidate immune correlate of protection and survival. This involves a series of challenge studies in which animals are vaccinated at a range of doses with the aim of achieving antibody levels that span a range of survival rates. This is needed so that the probability of survival for a human subject with a given antibody level can be precisely predicted when the corresponding human antibody levels become available from clinical trials. This precision is driven by the approximation of the parameter estimates for the modeled relationship; this in turn is driven by both the size of the NHP data set and the range of antibody levels seen in the data across the range of protection. It is particularly important to collect data for antibody levels achieving intermediate protection, not only at the extremes of 0% and 100% survival. Figure 1 shows an example of an estimated logistic relationship between vaccine-induced antibody levels pre-challenge (on the x axis) and the probability of survival at a given timepoint following challenge in NHPs (on the y axis). Each orange point represents individual NHPs that survived (at 1 on the y axis) and those that died (at 0 on the y axis), with their antibody level on the x axis. The blue dashed line is the estimated logistic model relating antibody level to the probability of survival based on the data set.