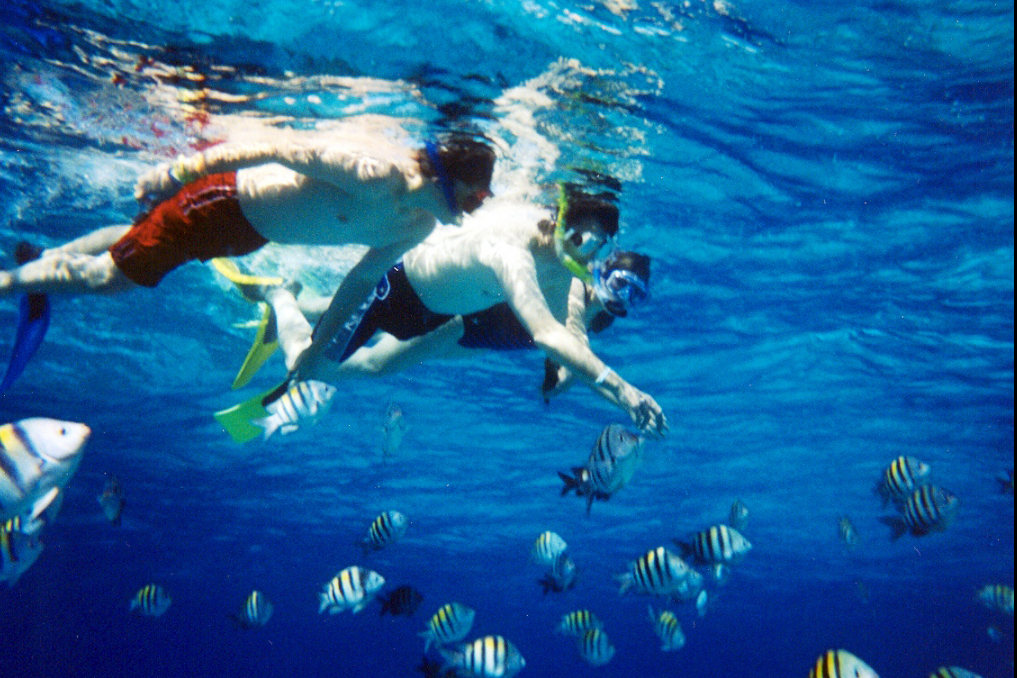

Snorkeling (British and Commonwealth English spelling: snorkelling) is the practice of swimming on or through a body of water while equipped with a diving mask, a shaped breathing tube called a snorkel, and usually swimfins. In cooler waters, a wetsuit may also be worn. Use of this equipment allows the snorkeler to observe underwater attractions for extended periods with relatively little effort and to breathe while face-down at the surface. Snorkeling is a popular recreational activity, particularly at tropical resort locations. The primary appeal is the opportunity to observe underwater life in a natural setting without the complicated equipment and training required for scuba diving. It appeals to all ages because of how little effort there is, and without the exhaled bubbles of scuba-diving equipment. It is the basis of the two surface disciplines of the underwater sport of finswimming. Snorkeling is also used by scuba divers when on the surface, in underwater sports such as underwater hockey and underwater rugby, and as part of water-based searches conducted by search and rescue teams.

- search and rescue

- snorkeling

- snorkelling

1. Equipment

Essential equipment includes the snorkel for breathing, and a diving mask or swimming goggles for vision. Swimfins for more efficient propulsion are common. Environmental protection against cold, sunburn and marine stings and scratches is also regionally popular, and may be in the form of a wetsuit, diving skins, or rash vest. Some snorkellers rely on waterproof sunscreen lotions, but some of these are environmentally damaging. If necessary the snorkeller may wear a weightbelt to facilitate freediving, or an inflatable snorkelling vest, a form of buoyancy aid, for safety.

1.1. Snorkel

A snorkel is a device used for breathing air from above the surface when the wearer's head is face downwards in the water with the mouth and the nose submerged. It may be either separate or integrated into a swimming or diving mask. The integrated version is only suitable for surface snorkeling, while the separate device may also be used for underwater activities such as spearfishing, freediving, finswimming, underwater hockey, underwater rugby and for surface breathing with scuba equipment. A swimmer's snorkel is a tube bent into a shape often resembling the letter "L" or "J", fitted with a mouthpiece at the lower end and constructed of light metal, rubber or plastic. The snorkel may come with a rubber loop or a plastic clip enabling the snorkel to be attached to the outside of the head strap of the diving mask. Although the snorkel may also be secured by tucking the tube between the mask-strap and the head, this alternative strategy can lead to physical discomfort, mask leakage or even snorkel loss.[1]

Snorkels constitute respiratory dead space. When the user takes in a fresh breath, some of the previously exhaled air which remains in the snorkel is inhaled again, reducing the amount of fresh air in the inhaled volume, and increasing the risk of a buildup of carbon dioxide in the blood, which can result in hypercapnia. The greater the volume of the tube, and the smaller the tidal volume of breathing, the more this problem is exacerbated. A smaller diameter tube reduces the dead volume, but also increases resistance to airflow and so increases the work of breathing. Including the internal volume of the mask in the breathing circuit greatly expands the dead space. Occasional exhalation through the nose while snorkeling with a separate snorkel will slightly reduce the buildup of carbon dioxide, and may help in keeping the mask clear of water, but in cold water it will increase fogging. To some extent the effect of dead space can be counteracted by breathing more deeply and slowly, as this reduces the dead space ratio and work of breathing.

Snorkels come in two orientations: Front-mounted and side-mounted. The first snorkel to be patented in 1938 was front-mounted, worn with the tube over the front of the face and secured with a bracket to the diving mask. Front-mounted snorkels proved popular in European snorkeling until the late 1950s, when side-mounted snorkels came into the ascendancy. Front-mounted snorkels experienced a comeback a decade later as a piece of competitive swimming equipment to be used in pool workouts and in finswimming races, where they outperform side-mounted snorkels in streamlining.

Plain snorkel

A plain snorkel consists essentially of a tube with a mouthpiece to be inserted between the lips.

The barrel is the hollow tube leading from the supply end at the top of the snorkel to the mouthpiece at the bottom. The barrel is made of a relatively rigid material such as plastic, light metal or hard rubber. The bore is the interior chamber of the barrel; bore length, diameter and bends all affect breathing resistance.

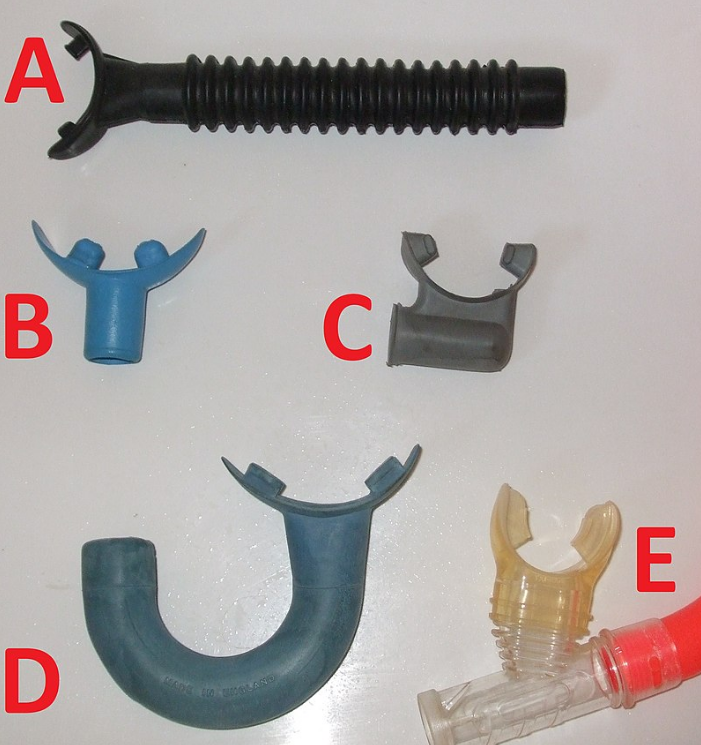

The top of the barrel may be open to the elements or fitted with a valve designed to shut off the air supply from the atmosphere when the top is submerged. There may be a high visibility band around the top to alert other water users of the snorkeller's presence. The simplest way of attaching the snorkel to the head is to slip the top of the barrel between the mask strap and the head. This may cause the mask to leak, however, and alternative means of attachment of the barrel to the head include threading the mask strap a moulded on the barrel, using a figure-8 rubber snorkel keeper pulled down over the barrel, or a rotatable plastic snorkel keeper clipped to the barrel

The mouthpiece helps to keep the snorkel in the mouth. It is made of soft and flexible material, originally natural rubber and more recently silicone or PVC. The commonest of the multiple designs available[2] features a slightly concave flange with two lugs to be gripped between the teeth: The tighter the teeth grip the mouthpiece lugs, the smaller the air gap between the teeth and the harder it will be to breathe. A tight grip with the teeth can also cause jaw fatigue and pain.

Full-face snorkel mask

An integrated snorkel consists essentially of a tube topped with a shut-off valve and opening at the bottom into the interior of a diving mask. Integrated snorkels must be fitted with valves to shut off the snorkel's air inlet when submerged. Water will otherwise pour into the opening at the top and flood the interior of the mask. Snorkels are attached to sockets on the top or the sides of the mask.

New-generation snorkel-masks are full-face masks covering the eyes, the nose and the mouth. They enable surface snorkellers to breathe nasally or orally and may be a workaround in the case of surface snorkellers who gag in response to the presence of standard snorkel mouthpieces in their mouths. Some early snorkel-masks are full-face masks covering the eyes, nose and mouth, while others exclude the mouth, covering the eyes and the nose only. The 1950s US Divers "Marino" hybrid comprised a single snorkel mask with eye and nose coverage and a separate snorkel for the mouth.[3]

Full face snorkel masks use an integral snorkel with separate channels for intake and exhaled gases theoretically ensuring the user is always breathing untainted fresh air whatever the respiratory effort. Built-in dry top snorkel system. In addition to a standard ball float system that stops the water from entering the tube when submerged, full-face masks are designed in such a way that even if a small amount of water does get into the snorkel, it will be channeled away from the face and into the chin area of the mask. A special valve located on the bottom of the chin allows to drain the water out. The main problem is that it must fit the whole face well enough to make a reliable seal and since no two faces are the same shape, it may not seal adequately on any specific user. In the event of accidental flooding, the whole mask must be removed to continue breathing.[clarification needed] Unless the snorkeler is able to equalize without pinching their nose it can only be used on the surface, or a couple of feet below, since the mask covers the nose with a rigid plastic structure, which makes it impossible to pinch the nose if needed to equalise pressure at greater depth. Trained scuba divers are likely to avoid such devices[4] however snorkel masks are a boon for those with medical conditions that preclude taking part in scuba diving.[clarification needed]

As a result of a short period with an unusually high number of snorkeling deaths in Hawaii[5] there is some suspicion that the design of the masks can result in buildup of excess CO2. It is far from certain that the masks are at fault, but the state of Hawaii has begun to track the equipment being used in cases of snorkeling fatalities. Besides the possibility that the masks, or at least some brands of the mask, are a cause, other theories include the possibility that the masks make snorkeling accessible to people who have difficulty with traditional snorkeling equipment. That ease of access may result in more snorkelers who lack experience or have underlying medical conditions, possibly exacerbating problems that are unrelated to the type of equipment being used.[6]

During the current 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic related shortages, full-face snorkel masks have been adapted to create oxygen dispensing emergency respiratory masks by deploying 3D printing and carrying out minimal modifications to the original mask.[7][8][9] Italian healthcare legislation requires patients to sign a declaration of acceptance of use of an uncertified biomedical device when they are given the modified snorkel mask for respiratory support interventions in the country's hospitals. France's main sportwear and snorkel masks producer Decathlon has discontinued its sale of snorkel masks, redirecting them instead toward medical staff, patients and 3D printer operations.[10]

1.2. Diving Mask

Snorkelers normally wear the same kind of mask as those worn by scuba divers. By creating an airspace, the mask enables the snorkeler to see clearly underwater. All scuba diving masks consist of the lenses also known as a faceplate, a soft rubber skirt, which encloses the nose and seals against the face, and a head strap to hold it in place. There are different styles and shapes. These range from oval shaped models to lower internal volume masks and may be made from different materials; common choices are silicone and rubber. A snorkeler who remains at the surface can use swimmer's goggles which do not enclose the nose.

1.3. Swimfins

Swimfins, fins or flippers are finlike accessories worn on the feet,[11] and usually made from rubber or plastic, to aid movement through the water in water sports activities. Swimfins help the wearer to move through water more efficiently, as human feet are too small and inappropriately shaped to provide much thrust, especially when the wearer is carrying equipment that increases hydrodynamic drag.[12][13][14] Very long fins and monofins used by freedivers as a means of underwater propulsion do not require high-frequency leg movement. This improves efficiency and helps to minimize oxygen consumption. Short, stiff-bladed fins are effective for short bursts of acceleration and maneuvering.

1.4. Exposure Protection

A wetsuit is a garment, usually made of foamed neoprene with a knit fabric facing, which is worn by people engaged in water sports and other activities in or on water, primarily providing thermal insulation, but also buoyancy and protection from abrasion, ultraviolet exposure and stings from marine organisms. The insulation properties depend on bubbles of gas enclosed within the material, which reduce its ability to conduct heat. The bubbles also give the wetsuit a low density, providing buoyancy in water. The thickness, fit and coverage of the suit are important factors for insulation.

Dive skins are used when diving in water temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F). They are usually one piece full length garments made from spandex or Lycra and provide little thermal protection, but do protect the skin from jellyfish stings, abrasion and sunburn. This kind of suit is also known as a 'Stinger Suit'. Some divers wear a dive skin under a wetsuit, which allows easier donning and (for those who experience skin problems from neoprene) provides additional comfort.[15]

A rash guard, also known as rash vest or rashie, is an athletic shirt made of spandex and nylon or polyester. The name rash guard reflects the fact that the shirt protects the wearer against rashes caused by abrasion, or by sunburn from extended exposure to the sun. These shirts can be worn by themselves, or under a wetsuit. A rash guard by itself is used for light coverage in warm to extreme summer temperatures for several watersports including snorkeling. There are also lower body rash guards, which are similar to compression shorts to be worn under the surfers' boardshorts.

1.5. Weight Belt

Weight belts are the most common weighting system currently in use for snorkeling.[16] They are generally made of tough nylon webbing, but other materials such as rubber can be used. Weight belts for snorkeling are generally fitted with a quick release buckle to allow the dumping of weight rapidly in an emergency.

The most common design of weight used with a belt is rectangular lead blocks with two slots in them threaded onto the belt. These blocks can be coated in plastic, which increases corrosion resistance. The plastic coated weights may be marketed as being less abrasive to wetsuits. The weights may be constrained from sliding along the webbing by metal or plastic belt sliders. Another popular style has a single slot through which the belt can be threaded. These are sometimes locked in position by squeezing the weight to grip the webbing, but this makes them difficult to remove when less weight is needed. There are also weight designs which may be added to the belt by clipping on when needed. The amount of weight needed depends mainly on the buoyancy of the wet suit.

1.6. Snorkeling Vest

An inflatable personal buoyancy aid designed for surface swimming applications. In shape, often like a horse-collar buoyancy compensator, or airline life jacket, but only with oral inflation or a CO2 cartridge for emergencies.

2. Operation

The simplest type of snorkel is a plain tube that is allowed to flood when underwater. The snorkeler expels water from the snorkel either with a sharp exhalation on return to the surface (blast clearing) or by tilting the head back shortly before reaching the surface and exhaling until reaching or breaking the surface (displacement method) and facing forward or down again before inhaling the next breath. The displacement method expels water by filling the snorkel with air; it is a technique that takes practice but clears the snorkel with less effort, but only works when surfacing. Clearing splash water while at the surface requires blast clearing.[17]

Experienced users tend to develop a surface breathing style which minimises work of breathing, carbon dioxide buildup and risk of water inspiration, while optimising water removal. This involves a sharp puff in the early stage of exhalation, which is effective for clearing the tube of remaining water, and a fairly large but comfortable exhaled volume, mostly fairly slowly for low work of breathing, followed by an immediate slow inhalation, which reduces entrainment of any residual water, to a comfortable but relatively large inhaled volume, repeated without delay. Elastic recoil is used to assist with the initial puff, which can be made sharper by controlling the start of exhalation with the tongue. This technique is most applicable to relaxed cruising on the surface. Racing finswimmers may use a different technique as they need a far greater level of ventilation when working hard.

Some snorkels have a sump at the lowest point to allow a small volume of water to remain in the snorkel without being inhaled when the snorkeler breathes. Some also have a non-return valve in the sump, to drain water in the tube when the diver exhales. The water is pushed out through the valve when the tube is blocked by water and the exhalation pressure exceeds the water pressure on the outside of the valve. This is almost exactly the mechanism of blast clearing which does not require the valve, but the pressure required is marginally less, and effective blast clearing requires a higher flow rate. The full face mask has a double airflow valve which allows breathing through the nose in addition to the mouth.[18] A few models of snorkel have float-operated valves attached to the top end of the tube to keep water out when a wave passes, but these cause problems when diving as the snorkel must then be equalized during descent, using part of the diver's inhaled air supply. Some recent designs have a splash deflector on the top end that reduces entry of any water that splashes over the top end of the tube, thereby keeping it relatively free from water.[19]

Finswimmers do not normally use snorkels with a sump valve, as they learn to blast clear the tube on most if not all exhalations, which keeps the water content in the tube to a minimum as the tube can be shaped for lower work of breathing, and elimination of water traps, allowing greater speed and lowering the stress of eventual swallowing of small quantities of water, which would impede their competition performance.[20]

A common problem with all mechanical clearing mechanisms is their tendency to fail if infrequently used, or if stored for long periods, or through environmental fouling, or owing to lack of maintenance. Many also either slightly increase the flow resistance of the snorkel, or provide a small water trap, which retains a little water in the tube after clearing.[21]

Modern designs use silicone rubber in the mouthpiece and one-way clearing and float valves due to its resistance to degradation and its long service life. Natural rubber was formerly used, but slowly oxidizes and breaks down due to ultraviolet light exposure from the sun. It eventually loses its flexibility, becomes brittle and cracks, which can cause clearing valves to stick in the open or closed position, and float valves to leak due to a failure of the valve seat to seal. In even older designs, some snorkels were made with small "ping pong" balls in a cage mounted to the open end of the tube to prevent water ingress. These are no longer sold or recommended because they are unreliable and considered hazardous. Similarly, diving masks with a built-in snorkel are considered unsafe by scuba diving organizations such as PADI, BSAC because they can engender a false sense of security and can be difficult to clear if flooded.

A snorkel may be either separate or integrated into a swim or dive mask. Usage of the term "snorkel" in this section excludes devices integrated with, and opening into, swimmers' or divers' masks. A separate snorkel typically comprises a tube for breathing and a means of attaching the tube to the head of the wearer. The tube has an opening at the top and a mouthpiece at the bottom. Some tubes are topped with a valve to prevent water from entering the tube when it is submerged.

The total length, inner diameter and/or inner volume of a snorkel tube are matters of utmost importance because they affect the user's ability to breathe normally while swimming or floating head downwards on the surface of the water. These dimensions also have implications for the user's ability to blow residual water out of the tube when surfacing. An overlong snorkel tube may cause breathing resistance, while an overwide tube may prove hard to clear of water. A high-volume tube is liable to encourage a build-up of stale air, including exhaled carbon dioxide, because it constitutes respiratory dead space.

3. Practice of Snorkeling

Snorkeling is an activity in its own right, as well as an adjunct to other activities, such as breath-hold diving, spearfishing and scuba diving,[22] and several competitive underwater sports, such as underwater hockey and finswimming. In all cases, the use of a snorkel facilitates breathing while swimming at the surface and observing what is going on under the water.

Being non-competitive, snorkeling is considered more a leisure activity than a sport.[23] Snorkeling requires no special training, only the very basic swimming abilities and being able to breathe through the snorkel.[24] Some organizations, such as BSAC, recommend that for snorkeling safety one should not snorkel alone,[25] but rather with a "buddy", a guide or a tour group.

Underwater photography has become more and more popular since the early 2000s, resulting in millions of pictures posted every year on various websites and social media. This mass of documentation is endowed with an enormous scientific potential, as millions of tourists possess a much superior coverage power than professional scientists, who can not allow themselves to spend so much time in the field. As a consequence, several participative sciences programs have been developed, supported by geo-localization and identification web sites, along with protocols for auto-organization and self-teaching aimed at biodiversity-interested snorkelers, in order for them to turn their observations into sound scientific data, available for research. This kind of approach has been successfully used in Réunion island, allowing for tens of new records and even new species.[26]

Snorkelers may progress to free-diving or recreational scuba diving, which should be preceded by at least some training from a dive instructor or experienced free-diver.

3.1. Safety Precautions

Some commercial snorkeling organizations require snorkelers at their venue to wear an inflatable vest, similar to a personal flotation device. They are usually bright yellow or orange and have a device that allows users to inflate or deflate the device to adjust their buoyancy. However, these devices hinder and prevent a snorkeler from free diving to any depth. Especially in cooler water, a wetsuit of appropriate thickness and coverage may be worn; wetsuits do provide some buoyancy without as much resistance to submersion. In the tropics, snorkelers (especially those with pale skin) often wear a rashguard or a shirt and/or board shorts in order to help protect the skin of the back and upper legs against sunburn.

The greatest danger to snorkelers are inshore and leisure craft such as jet skis, speed boats and the like. A snorkeler is often submerged in the water with only the tube visible above the surface. Since these craft can ply the same areas snorkelers visit, the chance for accidental collisions exists. Sailboats and sailboards are a particular hazard as their quiet propulsion systems may not alert the snorkeler of their presence. A snorkeler may surface underneath a vessel and/or be struck by it. Few locations demarcate small craft areas from snorkeling areas, unlike that done for regular beach-bathers, with areas marked by buoys. Snorkelers may therefore choose to wear bright or highly reflective colors/outfits and/or to employ dive flags to enable easy spotting by boaters and others.

Snorkelers' backs, ankles, and rear of their thighs can be exposed to the sun for extended periods, and can burn badly (even if slightly submerged), without being noticed in time. The wearing appropriate covering such as a "rash guard" with SPF (in warmer waters), a T-shirt, a wetsuit, and especially "waterproof" sunblock will mitigate this risk.

Dehydration is another concern. Hydrating well before entering the water is highly recommended, especially if one intends to snorkel for several hours. Proper hydration also prevents cramps. Snorkelers who hyperventilate to extend sub-surface time can experience hypocapnia if they hyperventilate prior to submerging. This can in turn lead to "shallow water blackout". Snorkeling with a buddy and remaining aware of the buddy's condition at all times can help avoid these difficulties.

When snorkeling on or near coral reefs, care must be exercised to avoid contact with the delicate (and sometimes sharp or stinging) coral, and its poisonous inhabitants, usually by wearing protective gloves and being careful of one's environment. Coral scrapes and cuts often require specialized first aid treatment and potentially, emergency medical treatment to avoid infection. Booties and surf shoes are especially useful as they allow trekking over reefs exposed by low tide, to access drop-offs or deeper waters of the outer reef—practices which are, however, considered ecologically irresponsible.

Contact with coral should always be avoided, because even boulder corals are fragile. Fin contact is a well-known cause of coral reef degradation.

Another safety concern is interaction and contact with the marine life during encounters. While seals and sea turtles can seem harmless and docile, they can become alarmed if approached or feel threatened. Some creatures, like moray eels, can hide in coral crevices and holes and will bite fingers in response to too much prodding. For these reasons, snorkeling websites often recommend an "observe but don't touch" etiquette when snorkeling.[27]

3.2. Snorkeling Locations

Snorkeling is possible in almost any body of water, but snorkelers are most likely to be found in locations where there are minimal waves, warm water, and something particularly interesting to see near the surface.

Generally shallow reefs ranging from 1 to 4 meters (3 to 13 ft) are favored by snorkelers. Enough water cover to swim over the top without kicking the bottom is needed, but shallow structure can be approached from the sides. Deeper reefs can also be explored, but repeated breath-holding to dive to those depths limits the number of practitioners, and raises the bar on the required fitness and skill level. Risk increases with increased depth and duration of the breath-hold excursions from the surface.

- Bog snorkeling: An individual sport, popular in the United Kingdom and Australia .

- Finswimming: An individual sport, the most popular competitive sport of CMAS, the only of this federation present in World Games. Finswimmers use a slightly different snorkel, suited for hydrodynamics and speed.

- Free-diving: Any form of diving without breathing apparatus, but often referring to competitive apnea as a sport.

- Scuba diving: A form of untethered diving using a self-contained portable breathing apparatus, frequently as a pastime.

- Spearfishing: Fishing with a spear often with snorkeling equipment, either for competitive sport or to obtain food.

- Underwater hockey: A competitive team-sport played in swimming pools using snorkeling equipment, sticks and a puck.

- Underwater rugby: A competitive team-sport played in deeper swimming pools using snorkeling equipment, baskets and a ball.

References

- Steve Blount and Herb Taylor, The Joy of Snorkeling, New York, NY: Pisces Book Company, 1984, p. 21.

- P. P. Serebrenitsky: Техника подводного спорта, Lenizdat, 1969, p. 92. Full text retrieved on 22 February, 2019 at http://ilovediving.ru/articles/maski-polumaski-ochki-dykhatelnye-trubki-lasty.

- Early Mfg. & Retailers - US Divers No.43. Retrieved on 26 February 2019 at http://www.skindivinghistory.com/mfg_retailers/u/US_Divers/43.html.

- "Full-Face Snorkeling Masks: Pros And Cons". https://dipndive.com/blog/full-face-snorkeling-masks-pros-and-cons.html. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- https://www.letsgotomaui.net/da-kine/full-face-snorkel-mask-dangers/

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/hawaii-full-face-snorkel-mask-related-deaths/

- Opoczynski, David (23 March 2020). "Coronavirus : quand les inventeurs viennent à la rescousse des hôpitaux". leparisien.fr. Retrieved 24 March 2020. http://www.leparisien.fr/societe/coronavirus-quand-les-inventeurs-viennent-a-la-rescousse-des-hopitaux-23-03-2020-8286186.php

- Video: Emergency mask for hospital ventilators. Retrieved 1 April 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w4Csqdxkrfw

- Easy COVID 19 emergency mask for hospital ventilators. Retrieved 24 March 2020. https://www.isinnova.it/easy-covid19-eng/

- Vidéo : Pourquoi ne pas distribuer des masques de plongée Décathlon? BFMTV répond à vos questions. Retrieved 1 April 2020. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=uZ5Vtf69cAA

- Alain Perrier, 250 réponses aux questions du plongeur curieux, Éditions du Gerfaut, Paris, 2008, ISBN:978-2-35191-033-7 (p.65, in French)

- Pendergast, DR; Mollendorf, J; Logue, C; Samimy, S (2003). "Evaluation of fins used in underwater swimming". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine (Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society) 30 (1): 57–73. PMID 12841609. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3936. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- "The influence of drag on human locomotion in water". Undersea Hyperb Med 32 (1): 45–57. 2005. PMID 15796314. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4037. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- "Energetics of underwater swimming with SCUBA". Med Sci Sports Exerc 28 (5): 573–80. May 1996. doi:10.1097/00005768-199605000-00006. PMID 9148086. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2F00005768-199605000-00006

- Staff (19 August 2014). "What Is The Difference Between Stinger Suit, Dive Skin, Wetsuit, Drysuit and Dive Suit". Ecostinger blog. EcoStinger. http://www.ecostinger.com/blog/what-is-the-difference-between-stinger-suit-dive-skin-wetsuit-drysuit-and-dive-suit-/. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Scuba diving air Regulators, buoyancy compensators scuba diving equipment, information advice help with scuba gear products safety - Philadelphia Area Dive Shops http://ygraine.membrane.com/enterhtml/live/scuba/products.html

- Underwater World, Unit 3- Diving Skills. Retrieved on 28 February 2019 at https://www.diveunderwaterworld.com/s/Chapter-3-Diving-Skills.pdf.

- Snorkel Ken, "Full Face Snorkel Mask Reviews | Tribord EasyBreathe Alternatives and Best Prices". Retrieved on 3 March 2019 at https://snorkelstore.net/full-face-snorkel-mask-review-lower-price-lower-quality/.

- US patent 5,404,872, Splash-guard for snorkel tubes, April 11, 1995. Retrieved on 1 March 2019 at https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/01/fe/9a/6038e50865f3f1/US5404872.pdf.

- Finswimming snorkels. Retrieved on 1 March 2019 at https://monofin.co.uk/blog-snorkels.html

- Snorkel Care. Retrieved on 1 March 2019 at https://www.scubadoctor.com.au/care-snorkel.htm.

- NOAA Diving Program (U.S.) (December 1979). "4 - Diving equipment". in Miller, James W.. NOAA Diving Manual, Diving for Science and Technology (2nd ed.). Silver Spring, Maryland: US Department of Commerce: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean Engineering. p. 24.

- Gayle Jennings (2 April 2007). Water-Based Tourism, Sport, Leisure, and Recreation Experiences. Routledge. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-1-136-34928-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=sBAGX5l5uuwC&pg=PA130.

- Fodor's (1988). Fodor's 89 Cancun, Cozumel, Merida, the Yucatan. Fodor's Travel Publications. ISBN 978-0-679-01610-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=lt5pggSPkwkC.

- Staff. "Snorkeling Safety". http://snorkelstore.net/snorkeling-safety/. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Bourjon, Philippe; Ducarme, Frédéric; Quod, Jean-Pascal; Sweet, Michael (2018). "Involving recreational snorkelers in inventory improvement or creation: a case study in the Indian Ocean". Cahiers de Biologie Marine 59: 451–460. doi:10.21411/CBM.A.B05FC714. https://dx.doi.org/10.21411%2FCBM.A.B05FC714

- The 5 Commandments of Snorkeling Etiquette, 2015 http://snorkelstore.net/the-5-commandments-of-snorkeling-etiquette/