Skin disease remains a common complaint among deployed service members. To mitigate the limited supply of dermatologists in the U.S. Military Health System, teledermatology has been harnessed as a specialist extender platform, allowing for online consultations in remote deployed settings. Operational teledermatology has played a critical role in reductions of medical evacuations with significant cost-savings. When direct in-person lesion visualization is unattainable, teledermoscopy can be harnessed as an effective diagnostic tool to distinguish suspicious skin lesions. Teledermoscopy has the versatile capacity for streamlined incorporation into the existing asynchronous telemedicine platforms utilized worldwide among deployed U.S. military healthcare providers. In terms of clinical utility, teledermoscopy offers a unique and timely opportunity to improve diagnostic accuracy, early detection rates, and prognostic courses for dermatological conditions. Such improvements will further reduce medical evacuations and separations, thereby improving mission readiness and combat effectiveness. As mission goals are safeguarded, associated operational budget costs are also preserved. This innovative, cost-effective technology merits integration into the U.S. Military Health System (MHS).

- teledermoscopy

- teledermatology

- military medicine

- operational dermatology

- occupational skin disease

- operational readiness

- combat effectiveness

- medical evacuation

- mission preparedness, medical readiness

- monkeypox pandemic

- COVID-19 pandemic

1. BackgIntrouductiond

Telemedicine harnesses technology-based software to deliver convenient and cost-effective medical care at a distance. Telehealth integration has been an ongoing evolution in the U.S. healthcare model. Telemeedicine was introduced as a healthcare delivery model in the 1960s and has become a permanent delivery system [1]. Telemedicine consultations provide timely and cost-effective health care services in garrison and deployed settings. Telemedicine delivery can be broadly organized into four modalities: real-time (synchronous), store-and-forward (asynchronous), remote patient monitoring (RPM), and mobile health (mHealth) [2].

Real-time telemedicine consultations are conducted via synchronous video and synchronous audio. This modality supports direct visual communications between the provider and the patient. The asynchronous, or store-and-forward (S& F) method, involves the electronic delivery of medical information (i.e., documents, images, videos) [2]. RPM is a technology that allows healthcare providers to synchronously monitor their patients outside conventional clinical settings (at home or in a remote area). Physicians can remotely access patient data, including physical symptoms, chronic conditions, post-hospitalization rehabilitation, and laboratory results [2]. Lastly, mobile health (mHealth) is a type of telemedicine modality that utilizes smartphone applications for healthcare delivery. With the advancement of smartphones and other health-related electronic devices, this modality has gained significant momentum in medical care systems [2]. Mobile health applications support biometric data tracking: calorie intake, exercise duration, pulse, blood pressure, weight, calorie intake, and sleep patterns. Likewise, further data can be collected and promptly delivered to healthcare providers to help monitor their patients’ health.

For the last three decades, the r the last three decades, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) has recognized telemedicine as a component of the U.S. Military Health System (MHS) [32]. Military telemedicine aims to improve access to specialized health care services in areas where military treatment facilities are limited or unavailable. [3,42,3]. Common modalities for military telehealth services include store-and-forward (asynchronous) systems, real-time (synchronous), and remote monitoring. Military dermatology frequently utilizes an asynchronous telemedicine model. Asynchronous delivery is a practical option for operational settings with a wide range of global time zones. Likewise, asynchronous delivery can be helpful to military dermatologists as photographs of cutaneous lesions can be further analyzed with computer software [43].

DuMoring the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic, teledermatology gained unprecedented interest among healthcare providers worldwide [5]. Insurance companies continue to modify their policies on physician reimbursements for teledermatology services, which has supported the expansion of this technology. Strict pandemic quarantine measures have prevented patients in rural and underserved communities from receiving timely dermatological care [6]. Teleeover, with recent advancements in technology and the internet, a dermatology has greatly increased access to dermatological care in the pandemic era [6].

Over the past three descope cades, the United States Military Health System has been be utilizing teledermatology technology. Teledermatology has enabled more efficient consultations and assessments. Through telemedicine platforms, service members can see a specialist within an average waiting time of 12–24 hours, in comparison to 4-8 weeks for in-person appointments [4]. Moreover, the DoD utied for remote synchronous visualization of teledermatology has produced significant operational cost-savings. Military teledermatology has prevented unnecessary medical evacuations, facilitated urgent consults, and reduced physicians’ cost of travel [4].

Dermskin lesions. This technoloscopgy is a noninvasive visualization method that facilitates the early diagnosis of time-critical skin lesions (e.g., malignant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma) by utilizing a dermatoscope [7,8]. A dermatoscope is a handheld device that contains an inbuilt illuminating system with a high magnifying power [7]. Similarly, treferred to as teledermoscopy. Teledermoscopy is a noninvasive diagnostic method that utilizes special instrumentation to assess cutaneous lesions when direct, clear visualization is challenging. Teledermoscophis practical technology is an invaluable option in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of dermatological conditions [7,84,5]. With t

Technological advancements in digital photography, teledeedermoscopy can accurately refine diagnosis and improve disease prognosis.

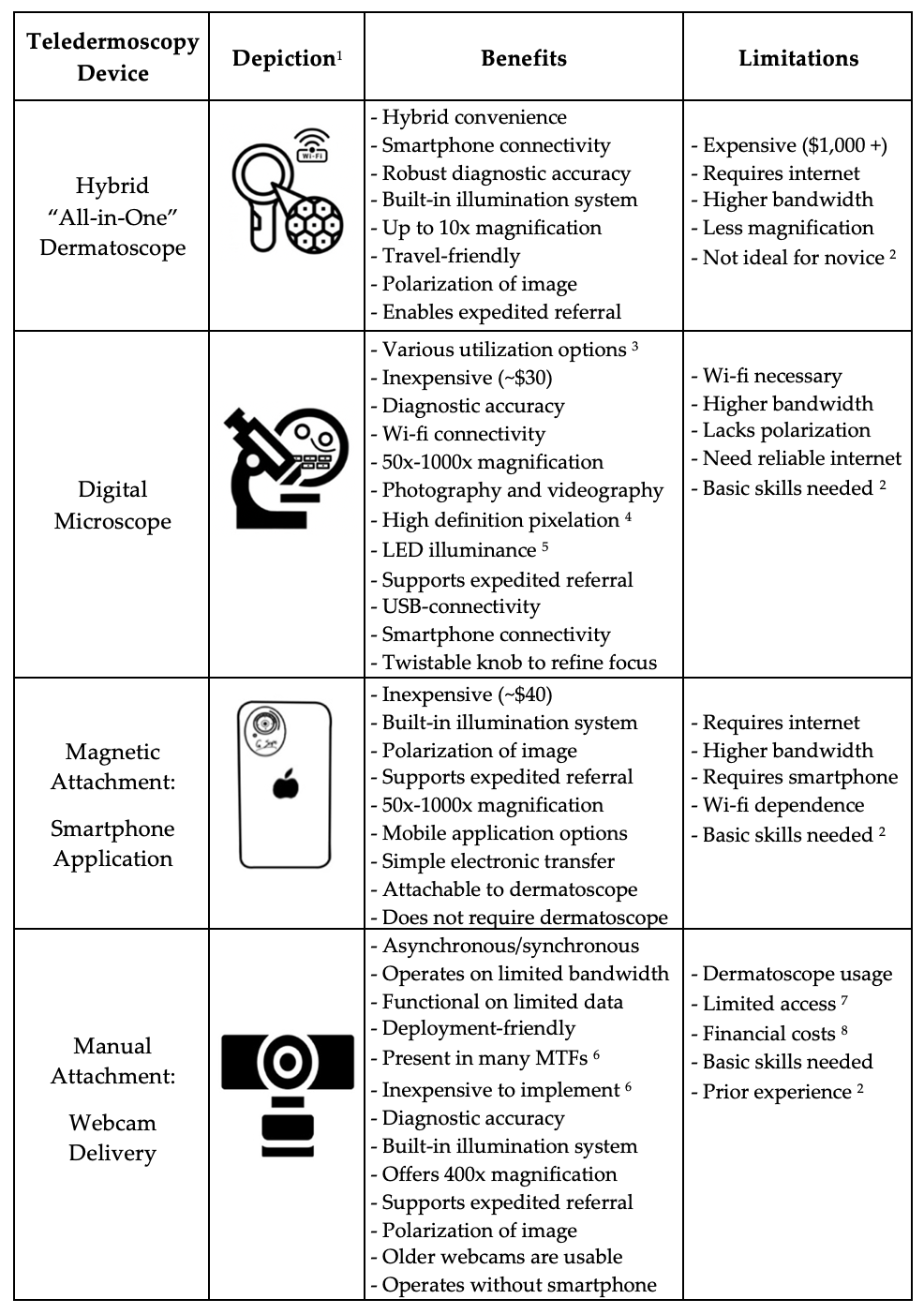

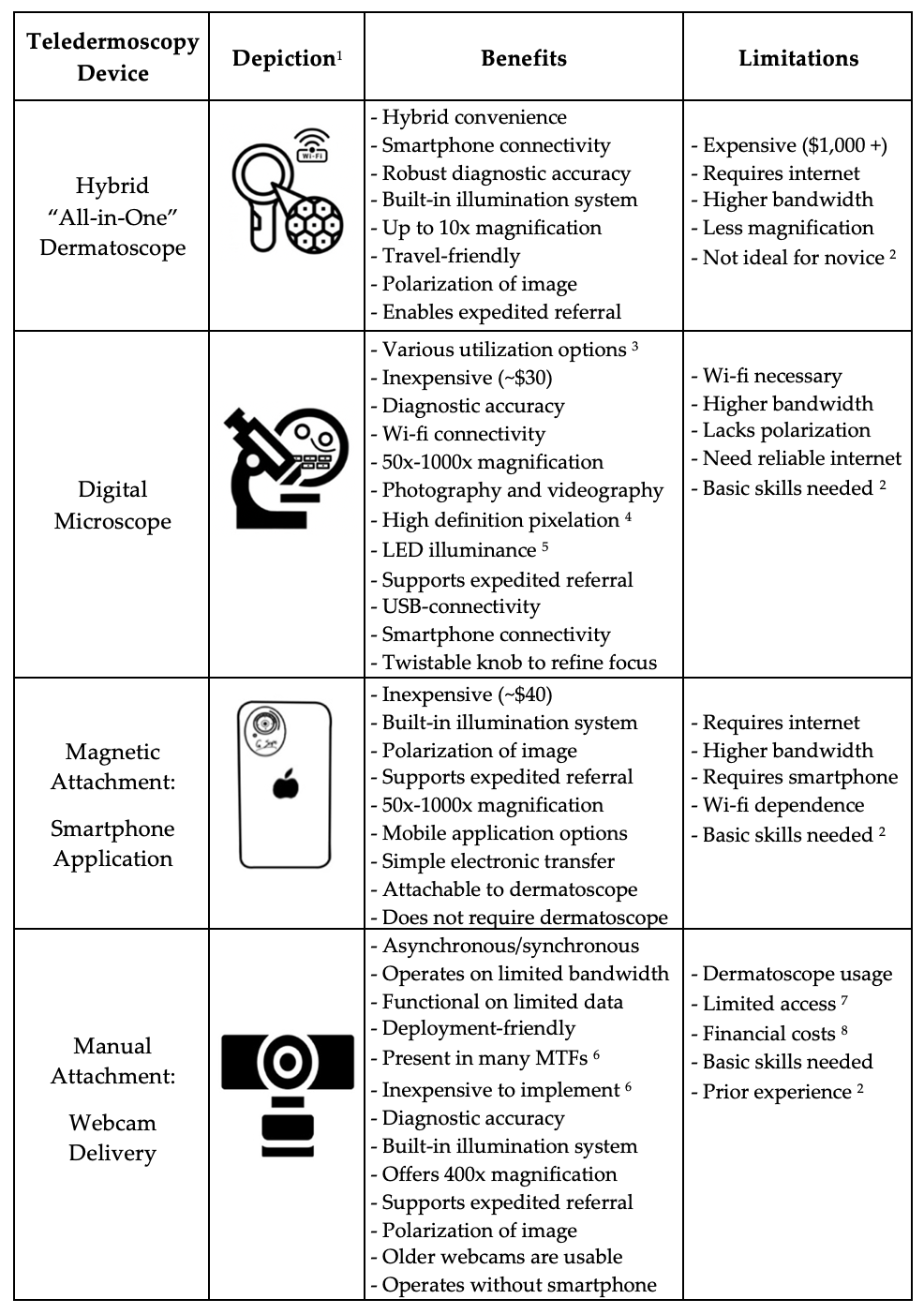

Te is a reledermoscopy has the capacity for real-time remote visualization of skin lesions, thereby assisting in timely treatments [9]. Dermatologists can visualize skin lesions synchronously from different angles and observe changes with varying applications of pressure (blanching, non-blanching, pitting, or non-pitting) [10]. Several technological modalities enable teledermoscopy delivery, such as the combined utilization of a video camera (webcam or a smartphone) and a dermatoscope or magnifying glass. Other modalities include an “all-in-one” system dermatoscope with a built-in digital camera and a wireless digital microscope that can be connected to mobile phones and personal computers [10].

With an arrtively new diagnostic tool that has not been widely adopted by dermay of device options, teledermoscopy offers economical and diagnostic benefit in military health systems all over the world. However, to date, only one military research study has evaluated the clinical utility of teleologists. Although teledermoscopy utilization in a military setting. This study was conducted in the United States (Navy Medical Corps) and evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of teledermoscopy in comparison to traditional in-person consultations with a board-certified dermatologist. This comparative study examined a variety of suspicious pigmented skin lesions and revealed matchedis a low-cost technology with high diagnostic accuracy between remote teledermoscopic and traditional in-person evaluations. These preliminary findings offer invaluable clinical insight and allude to other benefits that have yet to be documented. Although teledermoscopy is a low-cost technology, there is scant research on its value in dermatological practice [6,7]. Such limited literature underscores the need for further studies on teledermoscopy utilization, particularly in military healthcare settings [117].

WThis encyclope herein present a novel literature analysis to demonstratedia article provides an updated briefing on teledermoscopy research over the last two decades and reviews evidence for the integration of teledermoscopy in military medicine. This specialized analysis provides an updated briefing on Additionally, it highlights teledermoscopy research over the last two decades. In addition, this teledermoscopy report outlines:benefits such as delivery options, diagnostic efficacy, training opportunities, calculable financial benefits, clinical value in operational medicine, affordability of potential implementation, and overall relevance to mission-preparedness in a dynamic pandemic era.

2. ObjTectivechnological Evolution of Teledermoscopy

ThSe main objective of this paper is to present organized evidence to illustrate the wide range of potential benefits associated with military utilization of teledermoscopy in a dynamically changing world with ongoing pandemics and other bioterrorism threats. This review is systematically organized to present data for the rationale of veral technological modalities enable teledermoscopy application in support of mission effectiveness in the U.S. Military Health System.

Overview of Objectives

- Present multifaceted evidence for the integration of teledermoscopy to safeguard military missions and preserve operational budget costs.

- Report an updated briefing on teledermoscopy research over the last two decades.

- Outline modalities and other emerging technologies for teledermoscopy delivery.

- Highlight the clinical utility of teledermoscopy in early lesion identification and accurate diagnosis.

- Describe mission-related benefits associated with teledermoscopy utilization in operational settings: improved remote assessment of pigmented lesions and improved recognition when prompt biopsies are warranted.

- Highlight diagnostic longevity of teledermoscopy application: long-term management and surveillance of high-risk malignant skin cancers.

- Describe economic advantages associated with timely treatments in operational settings: reduced medical evacuations and separations.

- Depict incalculable benefits associated with accurate diagnosis and timely biopsies: improved prognosis, enhanced quality of life, and increased patient

- Underscore incalculable benefits due to avoided medical evacuations such as decreased dangers associated with traveling in potentially hostile environments.

- Outline potential mission strategies to overcome potential barriers in teledermoscopy military utilization.

- Highlight key roles of military dermatologists in operational settings: effective diagnostic strategies and timely treatments for potentially mission-disqualifying dermatological conditions.

- Discuss evolving trends that impact operational dermatology: mission readiness, combat effectiveness against pandemics, and other bioterrorism threats to security.

3. Materials and Methods

A literatdelivery, sure search was conducted to extrapolate research articles on PubMed and MEDLINE on telemedicine and teledermatology. The literature search was designed to extract research articles with a specific focus on teledermoscopy. Therefore, “teledermoscopy” was the only key term utilized in the literature search. Publication dates were set from 2000 to 2022. Articles written in a language other than English were excluded. Abstracts, animal research, and pending papers were excluded from the literature search. The search retrieved a total of 95 articles. All articles were initially examined by a reviewer (GP) and were screened based on title and abstract. Articles were originally included if it contained the utilized key term in its title or abstract. Following the preliminary screening, 75 pertinent randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, retrospective studies, prospective studies, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, topic reviews, qualitative studies, comparative analyses, pilot studies, observational studies, books, and case series were included. No meta-analyses were identified (within the scope of the investigation) at the time of the literature search.

4. Results

Althas the combined utilization of a video camera (webcam or a smartphone) and a dermatoscope or magnifying glass. Other modalities include an “all-in-one” system dermatoscope with a built-in digital camera and a wireless digital micrough a cost-effective technology, the comprehensive literature search dating over 22 years exposed scarce research on teledermoscopy and its clinical utility in dermatological practice. To date, only one research study has evaluated the diagnostic efficacy of teledermoscopy usage in a military setting. This milestone study was conducted in the United States (Navy Medical Corps) and revealed matched accuracy in remote teledermoscopic diagnosis compared to blinded, remote in-person evaluations with a board-certified dermatologist. Furthermore, this military study illustrated an inexpensive configuration option for the successful utilization of synchronous teledermoscopy in a military treatment facility. These promising results allude to opportunistic potential for operational dermatology. Such limited literature underscores the need for further research initiatives oncope that can be connected to mobile phones and personal computers [6] (Figure 1). There is a vast array of evidence that demonstrates the significant benefits of teledermoscopy utilization in a military healthcare setting [11]. With an increasing array atolof device options, teledermoscopy offers economical and diagnostic utility in the United States military.

5. Cost-Saving Benefits and Advantages of Teledermatology

Teledermatology reduces medical costs associated with dermatological care in the military [4]. It is estimated that the healthcare costs ble 1 organizes evidence associated with teledermatology visits can be reduced by $35 million annually if approximately 5% of the office-based visits are shifted to teledermatology [12]. When compared to in-person evaluations, teledermatology offers matched diagnostic accuracy in skin disease [13]usage in military health systems.

Figure 1. The most common skin conditions requiring teledermatology consultation include acne, atopic dermatitis, hair loss, and skin cancer [14]. Of note, patients with suspicious lesions should always consult board-certified dermatologists for a full body skin examination. However, in-person dermatological evaluations may not be feasible for patients in deployed settings [15]. In such cases, general practitioners can photograph lesions of concern or conduct a synchronous toscopy delivery. Overview of device options for teledermoscopy examination. Table 1 organizes evidence associated with teledermatology usage in military health systemsdelivery.

Table 1. Evidence of Teledermatology Benefits.

|

Benefits |

Research Evidence |

|

Healthcare Cost Reduction

|

- Minimize unnecessary medical evacuation [18] - Reduces dermatology referrals [19] |

|

Timely Treatments

|

- Triage of more urgent, complicated medical problems [18] - Faster diagnostic procedures, medical treatment, and surgery [12]

|

|

Medical Care Mobilization |

- U.S. VHA1 implementation increased access to care2 [20] - Face-to-face dermatological care is maintained virtually [21]

|

|

Early Lesion Detection

|

- Promotes timely treatment [18] - Improved prognosis [12] - Helpful triage for general practitioners [12,18]

|

|

Reduced Evacuations |

- Reduced time away from missions - Reduced appointment time to visit - Improved recovery time - Improved prognosis - Reduced medical discharge [18]

|

1 United States Veterans Health Administration.

2 From 2002-2014, the VA provided 234,928 teledermatology consultations (6% of all consultations) to veterans without local access to dermatologists.

6. The Technological Evolution of Teledermoscopy

The implementation of teledermoscopy can significantly improve early skin cancer detection than teledermatology alone [18]. Teledermoscopy can be harnessed as a practical diagnostic device to triage patients with skin conditions. With the advancement of technological delivery systems, primary care physicians and patients can conduct successful teledermoscopy sessions. Such advancements include smartphone-based microscopes, handheld digital microscopes, dermatoscopes with built-in camera systems, universal attachable dermatoscope lenses, and manual webcam attachments [18].

Smartphone microscopes are inexpensive and can provide high-quality diagnostic accuracy. These portable tools are widely available [21–23]. Smartphone microscopdevices are small magnifying lenses that attach to the back camera of a smartphone. Smartphone microscopes have a built-in illumination system and offer up to 40x magnification. These devices are travel-frietravel-friendly, inexpensive, and can be efficiently utilized by general practitioners to transfer photos of suspected lesions [18,218,9]. This practical process can aid in the elimination of unnecessary in-person consultation (and associated costs).

Additionally, Lika wewise, smartphone micrbcam in combination with a dermatoscopes can expedite referral for (or magnifying glass) can be utilized to visualize skin lesions that appear malignant. A study by Veronese et al. revealed an 80% diagnostic accuracy of a smartphone microscopeduring teledermatological consultations. Webcam device (NurugoTM) compars can be readily employed to a conventional dermatoscope [18]. These favorable results underscore the prudence for continued research onpractice teledermoscopy. The incorporation of teledermoscopy has further expanded the utility of teledermoscopy.

Iatology in addition to smartphone microsagnosing these skin lesions.

3. Teledermoscopy Data Underscores Potential Benefits for U.S. Military Health System

3.1 Faster Access to Dermatological Care

Sincopes, handheld digital microscopes are harnessed as a viable modality. Likewise, hybrid dermatoscope devices offer its inception in the military three decades ago, teledermoscopy delivery via an “all-in-one” system without requiring a direct contact application with a webcam, smartphone, or another camera device. The costliest of all described technologies, “all-in-one” dermatoscopes offer the superior convenience of using one compact tool and enable smartphone connectivity via Bluetooth capabilities. Likewise, universal dermoscopy lenses are designed to magnetically attach to various image-capturing devices: virtually any digital single lens reflex camera, compact point-and-shoot systems, mirrorless system cameraatology has enabled more efficient consultations and assessments. Through telemedicine platforms, service members can see a specialist within an average waiting time of 12–24 hours, in comparison to 4-8 weeks for in-person appointments [3]. Moreover, the DoD utilization of teledermatology has produced significant operational cost-savings. Military teledermatology has prevented unnecessary medical evacuations, facilitated urgent consults, and smartphone devices. These portable lenses offer reduced physicians’ cost of travel [3].

3.2 Operational Cost-Savings

Ithe unique convenience of multiple device compatibility, including smartphone devices.

Addiis estimated that the healthcare costionally,s a webcam in combinationssociated with a dermatoscope (or magnifying glass)logy visits can be utilized to visualize skin lesions during teledermatological consultations. Webcam devices can be readily employed to practice tereduced by $35 million annually if approximately 5% of the office-based visits are shifted to teledermoscopy. Likewise, all military dermatologists possess a dermatoscope and use dermoscopy in their daily practice [11]. The ubiquitous presence of webcam technology and personal atology [10]. A 2010 study evaluated a total of 2,197 store-and-forward teledermatoscopes bypasses the need for high financial investments for initialology consults generated by military implementation. [11] The widespread existence of webcam technology at MTFs offers a unique learning opportunity for graduate medical education. Basic practice with a combinhealth providers between the specified time frame: January 2005 through January 2009. This study found that teledermatology appropriately triaged dermatoscope and webcam application has the potential to boost dermoscopy skills in military residency training programs.

Lastly,ological cases and prevented unnecessary evacuation from the mission. The estimated total cost-saving from unnecessary evacuation during the period manualof webcam attachment uniquely supports synchronous and asynchronous tthe study was 30.4 million dollars [11]. Teledermoscopy delivery. An additional advantage, the manual attachment to webcams is not dependent on smartphone technologies. Furthermore, unlike smartphones, webcams can operate on minimal bandwidth (equivalent to one bar of data service). Such minimal bandwidth requirements support asynchronous delivery on the Defense Health Agency (DHA) Global Teleconsultational Portal (GTP) atology utilization also provides incalculable savings by avoidance of dangerous travel in a war zone [11]. These results underscore the magnitude of cost-savings associated with preventing medical evacuations in combat [11]. These simple yet effective features of webcam attachment delivery champion this modality as an affordable and pragmatic option for more widespread utilization of operational teledermoscopy in the United Military Health System [11Additional mission benefits that cannot be fully quantified include cost-savings associated with enriched quality of life-related to earlier care access and disease management [12–14]. Figu

3.3 Diagnostic Strength

More 1 provides an overview of different technologies employed in the delivery ofer, when compared to in-person evaluations, teledermoscopy. Table 2 illustrates the distinct benefits and limitations of each teledermoscopic modality.

Figure 1. Tatology offers matched diagnostic accuracy in skin disease [15]. The IMAGE IT Trial analyzed approximateledermoscopy delivery. Overview of device options for teledermoscopy delivery.

Table 2.five hundred skin lesions of concern independently assessed through Tteledermoscopy technologies. Summary of distinct benefits and limiand in-person consultations [16–18].

1 DeviceOut depictions are for illustrative purposes only.

2of 491 lesions of Pricor dermoscopy experience or basic training in dermoscopy is recommended for proper usagencern, only twelve malignant lesions were misreported as benign.

3 DHowelivery options include microscope base or free mobile application with hand.

4ver, when histopathology was Hutigh pixelation includes 2 million pixels: high definition 1080P HD picture quality.

5 Lilized, only one malight-emitnanting diodes (LED) contain properties of energy efficiency.

6 B lesion was missed (one basial c webcam technology exists in many military training facilities – cost-effective implementationell carcinoma misdiagnosed as a solar keratosis lesion) [17].

7 The IMAGE InT operational settings, dermatoscopes may not be readily available.

8 DermaTrial determined teledermoscopy evaluatioscopes are currently not included in the reimbursable medical allowance for deployment.

7. Teledermoscopy: Evidence for Military Implementation

7.1 Synchronous Teledermoscopy Study in U.S. Military Training Facility

Thn accuracy approximated United States Department of Defense has utilized telemedicine for over three decades and has significantly improved dermatology care for deployed service members [3]. Moreover,100% sensitivity and 90% specificity. The most common skin conditions requiring teledermatology consultation in military treatment facilities has the highest number of consults than any other specialty in the military [4]. Additionally, military dermatologists continue to expand teledermatology in the military by implementing new strategies for teledermoscopy deliveryclude acne, atopic dermatitis, hair loss, and skin cancer [19]. Teledermoscopy application improves the remote assessment of pigmented lesions and synergistically determines the potential need for prompt biopsy [16,18].

4. Cost-Effective Integration for U.S. Military Health System

Day et al. conducted the first military study (Navy Medical Corps) to evaluate teledermoscopy within a military health system worldwide. The study sought to compare the diagnostic accuracy of a teledermatology consultation using synchronous teledermoscopy and a traditional in-person dermatological consultation [117]. The study was conducted on two patients at a remote military medical clinic, and each provider was blinded to the lesion diagnosis. Each patient presented with two lesions (benign and malignant) that were examined by two board-certified dermatologists [117].

The teledermoscopy session utilized a repurposed webcam ubiquitous at most military training facilities (MTFs) and a dermatoscope (x10 magnification) with transillumination properties. Figure 2 depicts the primary protocol used for the synchronous teledermoscopy application. This military research study revealed both the in-person dermatologist and the remote dermatologist were in 100% concordance regarding the accurate diagnosis of each lesion as benign or malignant when using teledermoscopy [117].

Current practice standards for military telemedicine in a deployed setting involve the utilization of an asynchronous “store & forward” teledermatology format. Given the spread of worldwide time zones, the S&F asynchronous format has mobilized specialized care in the military. Deployed providers typically email a raw picture with a brief description to a centralized email address which forwards to military dermatologists.

While this study utilized a dermatoscope to visualize skin lesions, a basic magnifying glass (coupled with webcam) is a feasible option when dermatoscopes are otherwise unavailable. The versatility of teledermoscopy devices underscore its feasibility and affordability to general practitioners. This practical teledermoscopy delivery a sustainable option in operational settings with limited resources. Prompt visualization of dermatoscopic structures can benefit the timely diagnosis and treatments for deployed servicemembers.

Figure 2. Synchronous teledermoscopy protocol tested at a military training facility. Basic configuration for teledermoscopy. (A) Dermatoscope; (B) Cisco Jabber Webcam; (C) Sanitize dermatoscope and skin lesions with alcohol; (D) Gentle contact between webcam and dermatoscope.

7.2 Histopathological Correlations

DLikermoscopic images provide greater clarity and detail for melanocytic lesions. Dwise, all military dermatologists possess a dermatoscopes contain valuable properties (e.g., epiluminescence micr and use dermoscopy), which can provide vital insight into dermoscopic structures [24]. Dermoscopic structures have histopathological correlations, a critical differentiating factor between benign versus malignant lesions and associated prognoses [24]. Earlier visualization of dermoscopic findings assists rapid lesion identification in military telemedicine [25]. Figure 3 demonstrates the visualization of benign and malignant lesions using teledermoscopy.

Th in their daily practice [7]. The ubiquitous presence of webcam technology and personal dermatoscopes bypasses the need for high financial investme IMAGE IT Trial analyzed approximately five hundred skin lesions of concern independently assessed through teledermoscopy and in-person consults for initial military implementations [24–26]. Out of 491 lesions of concern, only twelve malignant lesions were misreported as benign. However, when histopath [7]. The widespread existence of webcam technology was utilized, only one malignant lesion was missed (one basal cell carcinoma misdiagnosed as a solar keratosis lesion) [25].at MTFs offers a unique learning opportunity for The IMAGE IT Tgrial determined teledermoscopy evaluation accuracy approximated 100% sensitivity and 90% specificity. The IMAGE IT Trial was conducted over a decade ago, and teledermoscopic technology has since exponentially advanced, suggesting even greater promise for excellent diagnostic reliability and successful implementation into clinical practice [25]. Likewise, teleaduate medical education. Basic practice with a combined dermatoscope and webcam application has the potential to boost dermoscopy offers diagnostic longevity for the long-term management and surveillance of patients at high risk for cutaneous malignant melanoma [27].

Teledermosskills in military residencopy application improves the remote assessment of pigmented lesions training programs.

Land synergistically determines the potential need for prompt biopsy [24,26]. Correct diagnosis and timely biopsies lead to incalculable benefits, including improved prognosis, quality of life, increased patient satisfaction, and decreased medical separation from military service.

Figure 3. Dtly, manual webcam attachment uniquely supports synchronous and asynchronous teledermoscopicy images: (A) Dyspdelastic Naevus; (B) Mvelanomary. in Situ; (C) Basal Cell CarcAn additionoma (low grade-nodular type).

7.3 Calculated Cost Savings in Operational Settings

Ial advantage, the mproved clianical outcomes ultimately reduce the need for medical evacuations, thereby improving combat effectiveness. Compared to the costs associated with dermatological evaluations overseas, the financial costs of evacuations overwhelmingly exceed in terms of fiscal impact [16,24,26]. A 2010 study evaluated a total of 2,197 store-and-forward teledermatology consults generated by military health providers between the specified time frame: January 2005 through January 2009. Each dermatological consultation followed the same process: deployed healthcare providers emailed digital kodachromes with a brief clinical history to one centrally monitored email address. All emails were then triaged to the on-call consulting dermatologist [16].

Thiual attachment to webcams is not dependent on smartphone technologies. Furthermore, unlike smartphones, webcams can operate on minimal bandwidth (equivalent to one bar of data service). Such minimal bandwidth requirements s study calculated the costs associated with medical evacuation to be exponentially far greater thapport asynchronous delivery on the costs related to providing specialized medical care. A summation of 1.4% Defense Health Agency (n = 40DHA) of the dermatoGlogical tbal Teleconsultations recommended evacuation back to the United States for an estimated cost of $562,380 [16al Portal (GTP) [7]. The total costs associated with medical evacuation included lost duty days, ground transportation, helicopter airlifts, extra personnel required security and transportation, meals, and temporary housing during evaluation and treatment [16]. The calculated analysis also revealed significant cost-savings associated with avoidance of medical evacuations [16]. With these simple yet effective features of webcam attachment delivery champion this modality as an affordable and pragmatic option for more widespread utilization of teledermatology, 2,157 military personnel were treated in Iraq, resulting in an estimated total cost-savings of 30.4 million dollars [16]. Teledermatology utilization also provides incalculable savings by avoidance of dangerous travel in a war zone [16]. These results underscore the magnitude of cost-savings associated with preventing medical evacuations in combat [16]. Additional mission operational teledermoscopy in the United Military Health System [7]. Table 2 illustrates the distinct benefits that cannot be fully quantified include cost-savings associated with enriched quality of life-related to earlier care access and disease management [29–31]and limitations of each teledermoscopic modality.

8. Teledermatology: Applications in a Pandemic Era

Withable 2. unprTecedented restrictions on societies, teledermatology has become increasingly utilized in a pandemic era [32]. With limited in-person interactions,ledermoscopy technologies. Summary of distinct benefits and limitations.

1 tDeledermatology has become a vital alternvice depictions are for illustrative to in-person dermatologypurposes only.

2 visits duPring global pandemics [33,34]. Teledermatology has made it easier for patients suffering from chronic skin conditions to continue seeing their dermatologists despite strict quarantine measures [34]. Additionally, teledermatology can be utilized to manage common ambulatory dermatoses and assess cutaneous manifestationsor dermoscopy experience or basic training in dermoscopy is recommended for proper usage.

3 of COVID-19 infections [33]. Such cutaneous manifestatelivery options include morbilliform rash, varicella-like rash, and livedo reticularis [14]. Many of these mild cutaneous conditions resolve spontaneously without medical intervention [14].

Additionally, icroscope base or free mobile application with the recentand.

4 emerHigence of the mutated Monkeypox virus, new cutaneous conditions continue to develop [14,35–37]. The rash associated with Monkeypox infection begins as a maculopapular rash that transforms into vesicles that scab and crust. The most common anatomical locations of the Monkeypoxh pixelation includes 2 million pixels: high definition 1080P HD picture quality.

5 vLirus include the face, extremities, groin, and other body parts [35,36]. Currently, there is no standard treatment protocol for the Monkeypox virus. It is theorized that the Smallpox vaccine may protect against the Monkeypoxght-emitting diodes (LED) contain properties of energy efficiency.

6 vBasirus. However, more research is needed to investigate the safety and confirm the efficacy of the proposed immunity.

As of Auc webcam technology exists in many military trainingust 2022, forty cases of Monkeypox have been identified across the Department of Defense [36]. The Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC) designed a specialized reportingfacilities – cost-effective implementation.

7 systemIn to ensure situoperational awareness and DoD-wide collation and tracking of Monkeypox infections. According to NMCPHC officials, the risk of Monkeypox infection among military personnel remains low [35,36]. The need for military dermatologists will steadily rise as the global landscape continues to shiftsettings, dermatoscopes may not be readily available.

8 Military dDermatologistsscopes are critical in correctly diagnosing and treating pandemic-related cutaneous conditions and operational skin lesions. As the ongoing need for military dermatologists increases much faster than provider availability, teledermatology remains a precious resource in the military health systemurrently not included in the reimbursable medical allowance for deployment.

95. Teledermoscopy: Opportunities to Address Healthcare Disparities Strategies for Successful Military Implementation

BTeyond operational settings, teleledermoscopy has a fitting role in rural regions, as remote areas experience significant shortages of access to board-certified dermatologists [33]. Many patients in these rural regions already have limited access to primary care providers. Likewise, patients in these regions cannot readily consult dermatologists for necessary evaluations of chronic and acute skin conditions [33]. Due to such high demand andoffers clinical utility in military medicine, with promising potential to support the medical readiness of the force. Despite feasible telehealth platforms for military implementation, operational settings present unique obstacles in telehealth delivery, including limited accessibility, obtaining an in-person dermatological consulbandwidth, ongoing staff permanent change of station may take weeks to months. The mobilization of teledermatology offers a lifeline to rural areas.

Fu(PCS) assignments, staff inexperience with derthermore, teledermatology increases access to specialized care in underserved niches, including correctional facilities and migrant camps [38,39]. The societal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the unprecedented and continued need for teledermatology expansion, particularly in rural settings [34]. To support public health needs, dermatologists should incorporate teledermatology into their practice model to help address dermatological care disparities in remote and underserved areasscopy, and limitations in authorized reimbursable medical allowance to military providers. Dermatoscopes are not currently authorized as reimbursable equipment in the designated medical allowance for deployed medical providers.

10. Teledermoscopy: Strategies for Successful Military Integration

Teledermoscopy offers clinical utility in military medicine, with promising potential to support the medical readiness of the force. Despite feasible telehealth platforms for military implementation, operational settings present unique obstacles in telehealth delivery, including limited bandwidth, ongoing staff permanent change of station (PCS) assignments, staff inexperience with dermoscopy, and limitations in authorized reimbursable medical allowance to military providers. Dermatoscopes are not currently authorized as reimbursable equipment in the designated medical allowance for deployed medical providers.

105.1 STechnololugical Options for Limited Bandwidth Connectivity

Existing technologies can mitigate obstacles in limited bandwidth connectivity. In terms of technological implementation, teledermoscopy fits appropriately into the Defense Health Agency (DHA) Global Teleconsultational Portal (GTP) [4022–4224]. Enacted in 2021, GTP is an asynchronous virtual medical center (VMC) currently utilized in the United States Military Health System (MSH). GTP was derived from the merger of the Pacific Asynchronous TeleHealth and the Health Experts Online Portal (PATH/HELP) systems which previously enabled provider-to-provider teleconsultation and patient support to the MHS. Since 2004, GTP has operated as a worldwide accessible, HIPAA-compliant, secure, web-based system for military health care personnel and providers [42]. GTP has been widely used to access medical specialists, such as board-certified military dermatologists [4224].

Interestingly, GTP can operate on a web browser with limited internet bandwidth, affording the unique opportunity to be utilized at military treatment levels [242]. Limited bandwidth due to poor data service can limit the transmissibility of medical data. As such, these technological adaptations allow for continued streaming at limited bandwidths via the Defense Health Agency Global Teleconsultational Portal, which operates on low bandwidth connectivity – equivalent to “one bar of service” in cellular usage [4224].

105.2 SoluTraining Metionhods for Military Staff Relocation & Inexperience with DeImproving Teledermoscopyic Diagnosis

A comparative study assessed teledermoscopy versus clinical examination in the accurate identification of skin cancers. Results revealed high diagnostic accuracy of skin cancers via teledermoscopy. Additionally, this investigation demonstrated consistent diagnostic accuracy among general practitioners and surgeons [285]. Various factors attributed to proper diagnostic consensus including a six-hour training course, photography quality, systematic methodology, ABCDE clinical algorithm implementation, and data acquisition software [285].

The research study implemented a training course focused on two major domains: clinical diagnosis of skin cancer (per the ABCDE clinical algorithm) and proper acquisition of teledermoscopic images. The ABCDE algorithm taught providers important clinical factors in the assessment of suspicious lesions. A skin lesion was deemed suspicious if a minimum two of the following three criteria were graded positive: A – asymmetry; C – color; E – evolution. Training for proper acquisition of teledermoscopic images included hands-on training to utilize a teledermoscopic system: digital dermatoscope and specialized teledermoscopy data acquisition software. Providers were also taught to collect relevant clinical data points (patient identification, Fitzpatrick skin phototype, skin cancer risk factors, anatomical region of concern, relevant ABCDE criteria) to produce a teledermoscopic report. Figure 3 illustrates quality dermoscopic images obtained in the study [285]. These successful findings in diagnostic accuracy are suggestive to the spectrum of options to deliver focused teledermoscopy training for general providers. Selective teledermoscopy education could yield great benefits for military healthcare providers, especially those in critical settings where dermatologists are in limited supply.

10

Figure 3. Dermoscopic images: (A) Dysplastic Naevus; (B) Melanoma in Situ; (C) Basal Cell Carcinoma (low grade-nodular type).

5.3 SoTelutions for Military Staff Reloedermoscopy Education & Inexperience with Dermofor New Providerscopy

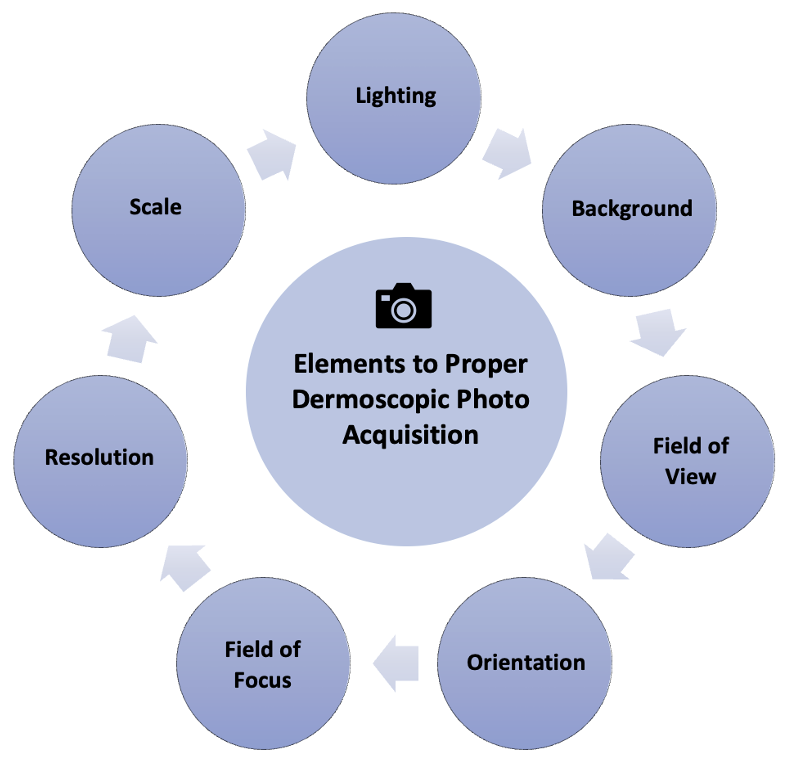

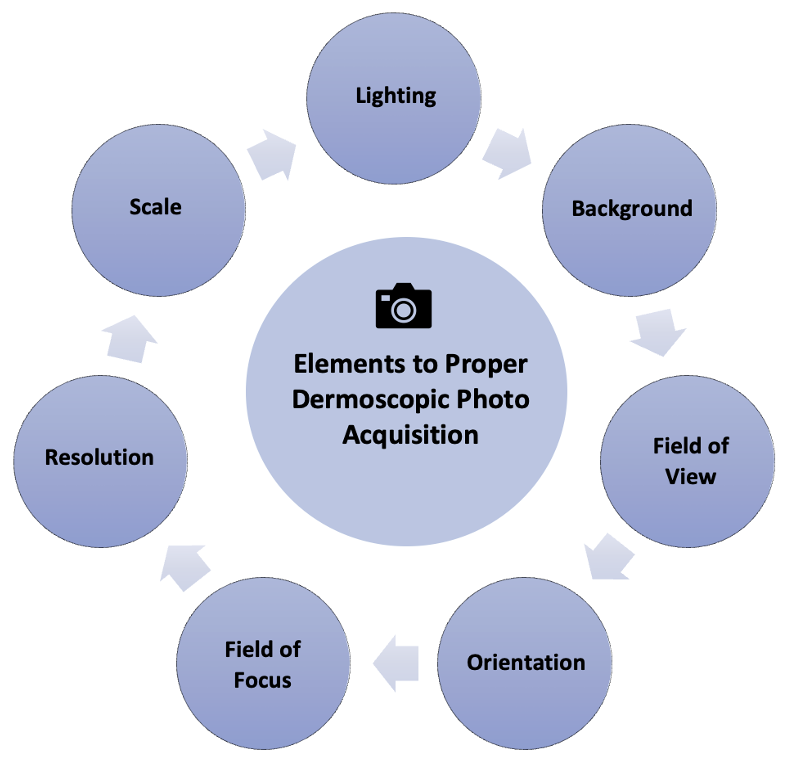

The transient nature of military staff assignments leads to more frequent staff turnover. This recurrent turnover may lead to new medical support staff with little to no experience in teledermoscopy. Such inexperience may impede successful teledermoscopy delivery. Nonetheless, these barriers can be overcome by concise training to ensure basic competency. For example, a pragmatic option for teledermoscopy training could involve a demonstration video that teaches proper utilization for best diagnostic outcomes. Figure 4 features key points for ideal acquisition of dermoscopic images.

Figure 4. Key elements for the successful acquisition of clinical images for asynchronous teledermatology consultations. Important delivery considerations include appropriate lighting, background, field of view, orientation, focus, field, resolution, and photo scale.

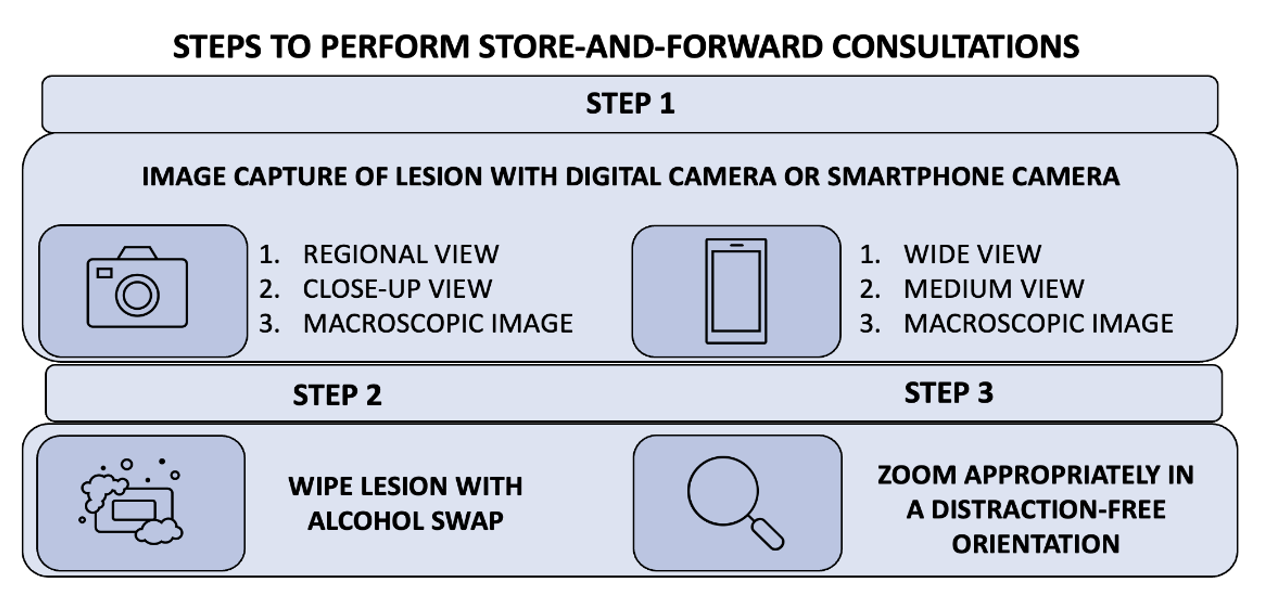

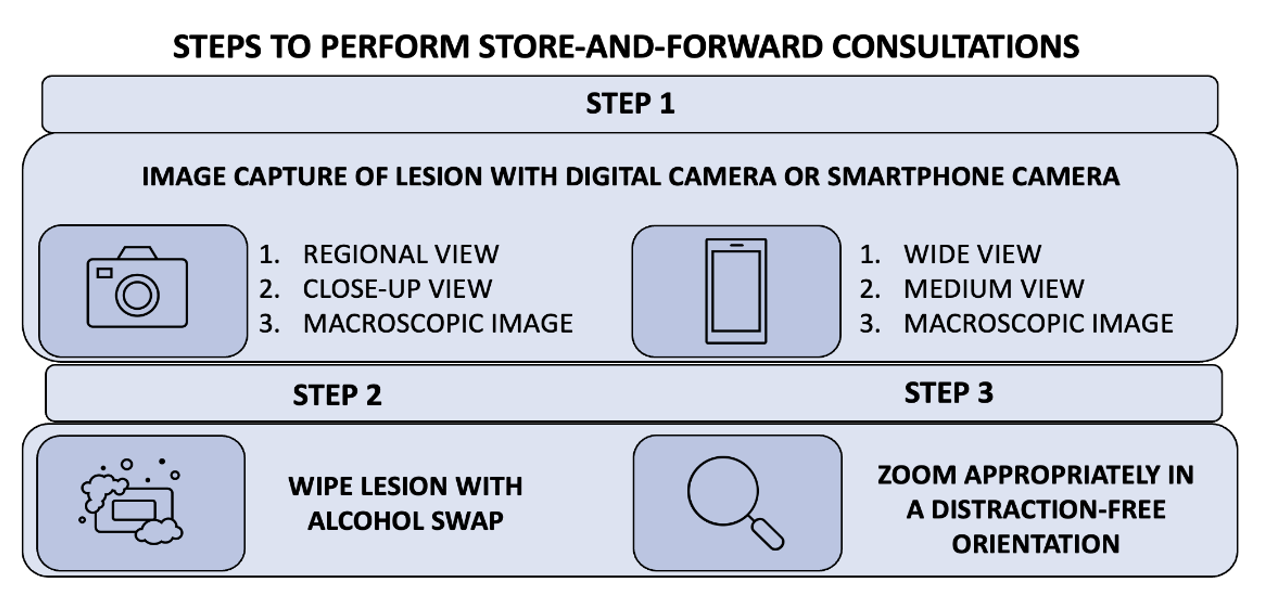

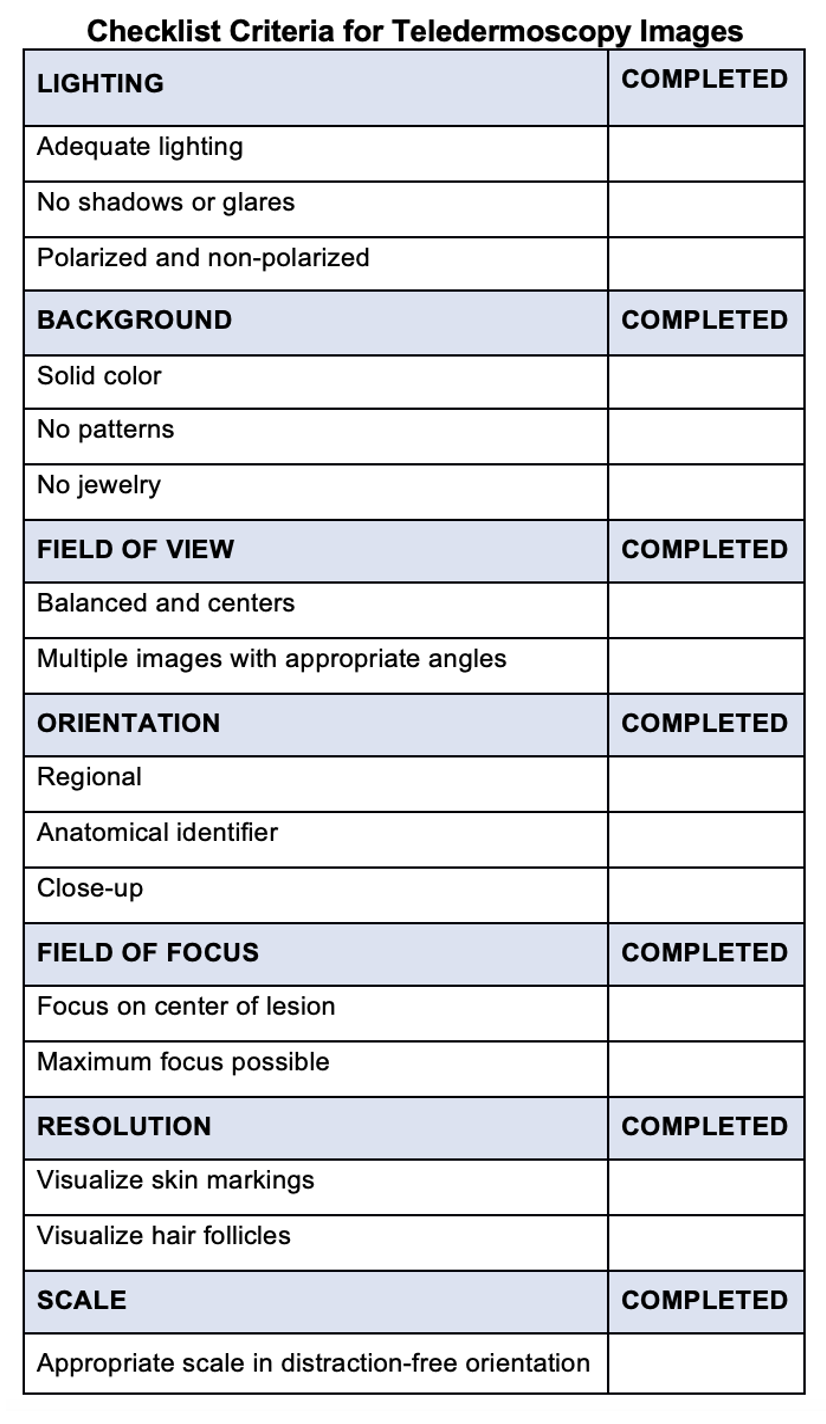

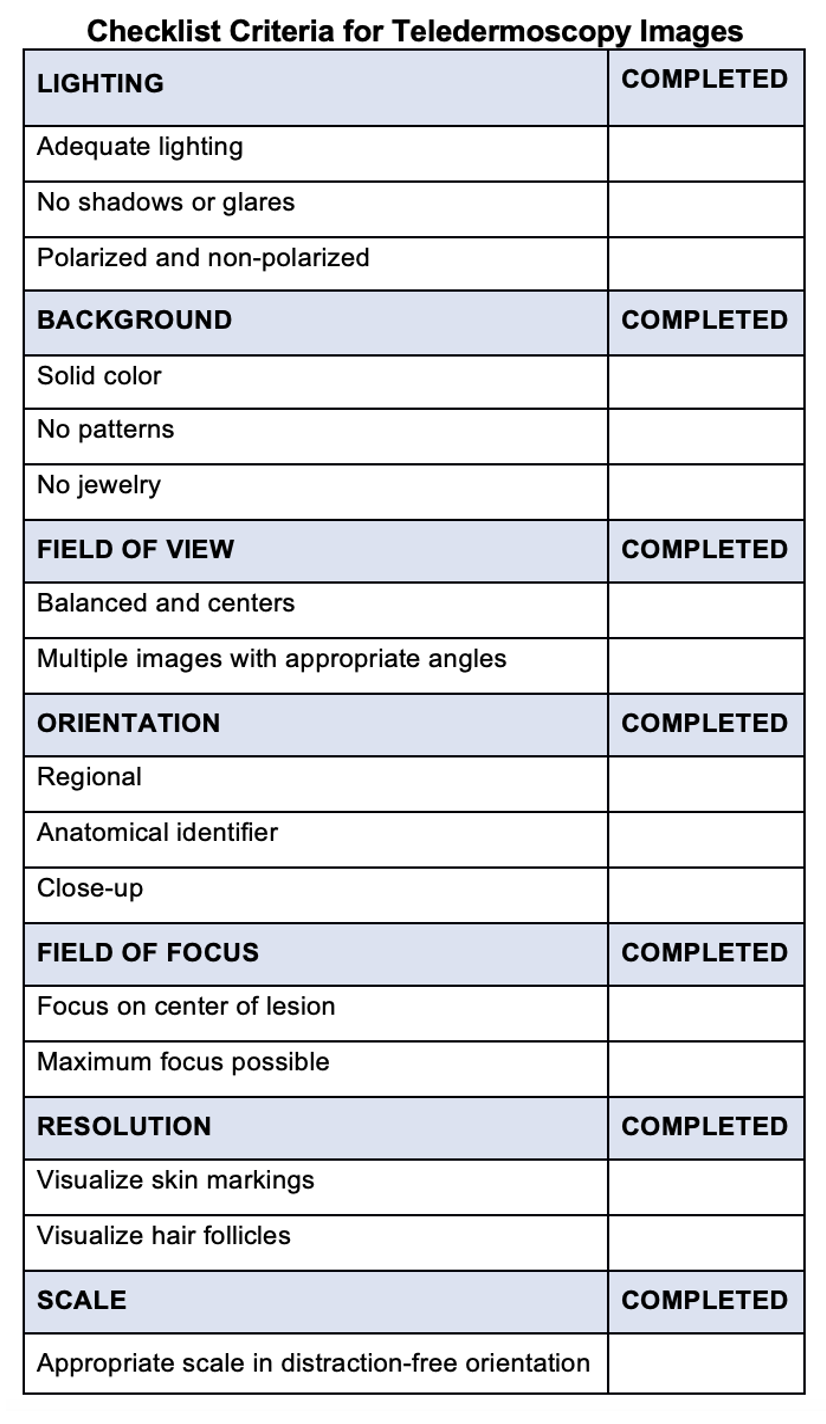

Figure 5 outlines best practices to capture teledermoscopic images for asynchronous delivery, commonly used in operational dermatology. Figure 6 provides a checklist of recommendations to ensure high-quality teledermoscopic images via an asynchronous store-and-forward telemedicine consultation. Important delivery considerations include appropriate lighting, background, the field of view, orientation, focus, field, resolution, and photo scale. The implementation of dermoscopy algorithms can increase the sensitivity, specificity, and early detection of critical lesions, including skin cancers, compared to examination by the naked eye [4326]. Likewise, dermoscopy can lead to the detection of thinner and smaller cancers. Such a diagnostic sensitivity is critical to mission effectiveness and decreased evacuations. With basic instruction, operational teledermoscopy could be successfully incorporated into the existing “store-and-forward” asynchronous military telemedicine platform.

Figure 5. Teledermoscopy using an asynchronous delivery system. The summary of three key steps describes how to perform teledermoscopy via an asynchronous store-and-forward telemedicine consultation successfully. Asynchronous teledermatology is widely utilized in operational dermatology.

Figure 6. Checklist criteria for teledermoscopy images. The checklist provides recommendations to ensure high-quality teledermoscopic images via an asynchronous store-and-forward telemedicine consultation. Important delivery considerations include appropriate lighting, background, field of view, orientation, field of focus, resolution, and orientation.

10

5.4 Dermatoscope Inclusion on Authorized Medical Allowance List

A valuable strategy for successful military integration of teledermoscopy includes the necessary inclusion of a dermatoscope in the designated Authorized Medical Allowance List (AMAL) for deployed personnel. A traditional dermatoscope can be harnessed into a valuable tool for teledermoscopy. Usage of a traditional dermatoscope can be readily implemented into the existing “store and forward” asynchronous military telemedicine healthcare delivery system for deployed personnel.

Military personnel often engage in operational requirements that increase their ultraviolet light exposure [4427]. Likewise, sunscreen protection and sun-protective clothing are underutilized among military personnel, particularly in a deployed setting [4528]. Furthermore, military (current and prior service) demographics include two groups who are predisposed to high rates of skin cancer: Caucasians (Fitzpatrick phototype II) and men over the age of 50 [4629]. With the compounded risks of skin cancer among military personnel, it is prudent to include dermatoscopes as part of the designated medical allowance for deployed military providers. Dermatoscopes empower providers to detect lesions earlier in the disease course, significantly improving lesion prognosis and associated disease mortality reduction. With webcam technology readily available at most military training facilities (MTFs), teledermoscopy merits inclusion in the utilization of military telemedicine [117].

116. Conclusion

In military operational settings, primary healthcare providers provide most dermatologic care yet remain in limited supply. Due to the high demand and limited availability of dermatologists, teledermatology is an exceptional specialist extender that allows medical providers worldwide access to dermatology consultations.

Teledermatology plays a critical role in reduced medical evacuations and associated cost-savings. As a valuable diagnostic feature of teledermatology, teledermoscopy integration into the military healthcare system is merited. With versatile diagnostic capacity, teledermoscopy can provide synchronous real-time remote visualization of skin lesions, facilitating faster diagnosis, timely treatments, and reduced medical evacuations. Likewise, teledermoscopy can be readily integrated into a “store-and-forward” asynchronous teledermatology platform, as commonly utilized in the United States Military Health System (MHS).

As society continues to evolve in a pandemic era with bioterrorism threats, the United States Military Health System must also adapt to meet the critical need for swift diagnosis and prompt treatment. Currently, no teledermoscopy practice guidelines exist, presenting a unique leadership opportunity to establish clinical standards. Such initiatives could set a meaningful precedent for the nation to follow suit and improve prognosis of potentially fatal dermatological conditions. Improved clinical outcomes ultimately reduce medical evacuations, thereby improving medical readiness and combat effectiveness. As mission goals are safeguarded, associated operational budget costs are also preserved.

References

- Board on Health Care Services. The Evolution of Telehealth: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going? National Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012.

- Poropatich, R.; Lappan, C.; Gilbert, G. Telehealth in the Department of Defense. In Understanding Telehealth; Rheuban, K.S., Krupinski, E.A., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Teledermatology in the US Military: A Historic Foundation for Current and Future Applications. Available online: https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/164865/practicemanagement/teledermatology-us-military-historic-foundation (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Sonthalia, S.; Yumeen, S.; Kaliyadan, F. Dermoscopy Overview and Extradiagnostic Applications; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022.

- Argenziano, G.; Soyer, H.P. Dermoscopy of Pigmented Skin Lesions—A Valuable Tool for Early Diagnosis of Melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2001, 2, 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00422-8.

- Uppal, S.K.; Beer, J.; Hadeler, E.; Gitlow, H.; Nouri, K. The Clinical Utility of Teledermoscopy in the Era of Telemedicine. Ther. 2021, 34, e14766. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14766.

- Day, W.G.; Shrivastava, V.; Roman, J.W. Synchronous Teledermoscopy in Military Treatment Facilities. Med. 2020, 185, e1334–e1337. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz479.

- Veronese, F.; Branciforti, F.; Zavattaro, E.; Tarantino, V.; Romano, V.; Meiburger, K.M.; Salvi, M.; Seoni, S.; Savoia, P. The Role in Teledermoscopy of an Inexpensive and Easy-to-Use Smartphone Device for the Classification of Three Types of Skin Lesions Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11030451.

- Coates, S.J.; Kvedar, J.; Granstein, R.D. Teledermatology: From Historical Perspective to Emerging Techniques of the Modern Era: Part II: Emerging Technologies in Teledermatology, Limitations and Future Directions. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 577–586; quiz 587–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.014.

- Wang, R.H.; Barbieri, J.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Stavert, R.; Forman, H.P.; Bolognia, J.L.; Kovarik, C.L. Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Teledermatology: Where Are We Now and What Are the Barriers to Adoption? Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.065.

- Teledermatology from a Combat Zone | Dermatology | JAMA Dermatology | JAMA Network. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/209971 (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Snoswell, C.L.; Caffery, L.J.; Whitty, J.A.; Soyer, H.P.; Gordon, L.G. Cost-Effectiveness of Skin Cancer Referral and Consultation Using Teledermoscopy in Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0855.

- Wootton, R.; Bloomer, S.E.; Corbett, R.; Eedy, D.J.; Hicks, N.; Lotery, H.E.; Mathews, C.; Paisley, J.; Steele, K.; Loane, M.A. Multicentre Randomised Control Trial Comparing Real Time Teledermatology with Conventional Outpatient Dermatological Care: Societal Cost-Benefit Analysis. BMJ 2000, 320, 1252–1256. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1252.

- Naka, F.; Lu, J.; Porto, A.; Villagra, J.; Wu, Z.H.; Anderson, D. Impact of Dermatology EConsults on Access to Care and Skin Cancer Screening in Underserved Populations: A Model for Teledermatology Services in Community Health Centers. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.017.

- Beer, J.; Hadeler, E.; Calume, A.; Gitlow, H.; Nouri, K. Teledermatology: Current Indications and Considerations for Future Use. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-020-02145-3.

- Lee, K.J.; Finnane, A.; Soyer, H.P. Recent Trends in Teledermatology and Teledermoscopy. Pract. Concept. 2018, 8, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.0803a13.

- Tan, E.; Yung, A.; Jameson, M.; Oakley, A.; Rademaker, M. Successful Triage of Patients Referred to a Skin Lesion Clinic Using Teledermoscopy (IMAGE IT Trial). J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 803–811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09673.x.

- Altayeb, A.; Dawood, S.; Atwan, A.; Mills, C. Teledermoscopy: A Helpful Detection Tool for Amelanotic and Hypomelanotic Melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 1244–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20609.

- Pendlebury, G.A.; Oro, P.; Haynes, W.; Merideth, D.; Bartling, S.; Bongiorno, M.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Dermatological Conditions: A Novel, Comprehensive Review. Dermatopathology 2022, 9, 212–243. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology9030027.

- Landow, S.M.; Oh, D.H.; Weinstock, M.A. Teledermatology Within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002–2014. e-Health 2015, 21, 769–773. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0225.

- Raugi, G.J.; Nelson, W.; Miethke, M.; Boyd, M.; Markham, C.; Dougall, B.; Bratten, D.; Comer, T. Teledermatology Implementation in a VHA Secondary Treatment Facility Improves Access to Face-to-Face Care. e-Health 2016, 22, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0036.

- GTP (v5.0)—Login. Available online: https://help.nmcp.med.navy.mil/path/user/ViewLogin.action (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Defense Health Agency. PATH & HELP to Transition to GTP; Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://path.tamc.amedd.army.mil/path/pdf/GTP_Transition2.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Reynolds, N. “Defense Health Agency (DHA) Update on Virtual Health (VH) for Defense Health Board” Presentation, Virtual. 30 March 2022. Available online: https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Meeting-References/2022/03/30/Defense-Health-Agency-Update-on-Virtual-Health (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Bandic, J.; Kovacevic, S.; Karabeg, R.; Lazarov, A.; Opric, D. Teledermoscopy for Skin Cancer Prevention: A Comparative Study of Clinical and Teledermoscopic Diagnosis. Acta Inform Med 2020, 28, 37–41, doi:10.5455/aim.2020.28.37-41.

- Holmes, G.A.; Vassantachart, J.M.; Limone, B.A.; Zumwalt, M.; Hirokane, J.; Jacob, S.E. Using Dermoscopy to Identify Melanoma and Improve Diagnostic Discrimination. Pract. 2018, 35, S39–S45.

- Gall, R.; Bongiorno, M.; Handfield, K. Skin Cancer in the US Military. Cutis 2021, 107, 29–33. https://doi.org/10.12788/cutis.0153.

- Powers, J.G.; Patel, N.A.; Powers, E.M.; Mayer, J.E.; Stricklin, G.P.; Geller, A.C. Skin Cancer Risk Factors and Preventative Behaviors among United States Military Veterans Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2871–2873. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.238.

- Riemenschneider, K.; Liu, J.; Powers, J.G. Skin Cancer in the Military: A Systematic Review of Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Incidence, Prevention, and Screening among Active Duty and Veteran Personnel. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062.

- Board on Health Care Services. The Evolution of Telehealth: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going? National Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012.

- Marcoux, R.M.; Vogenberg, F.R. Telehealth: Applications From a Legal and Regulatory Perspective. Ther. 2016, 41, 567–570.

- Poropatich, R.; Lappan, C.; Gilbert, G. Telehealth in the Department of Defense. In Understanding Telehealth; Rheuban, K.S., Krupinski, E.A., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Teledermatology in the US Military: A Historic Foundation for Current and Future Applications. Available online: https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/164865/practice-management/teledermatology-us-military-historic-foundation (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Yeboah, C.B.; Harvey, N.; Krishnan, R.; Lipoff, J.B. The Impact of COVID-19 on Teledermatology. Clin. 2021, 39, 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2021.05.007.

- Gao, J.C.; Zhang, A.; Gomolin, T.; Cabral, D.; Cline, A.; Marmon, S. Accessibility of Direct-to-Consumer Teledermatology to Underserved Populations. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 86, e133–e134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.043.

- Sonthalia, S.; Yumeen, S.; Kaliyadan, F. Dermoscopy Overview and Extradiagnostic Applications; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022.

- Argenziano, G.; Soyer, H.P. Dermoscopy of Pigmented Skin Lesions—A Valuable Tool for Early Diagnosis of Melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2001, 2, 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00422-8.

- Bruce, A.F.; Mallow, J.A.; Theeke, L.A. The Use of Teledermoscopy in the Accurate Identification of Cancerous Skin Lesions in the Adult Population: A Systematic Review. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16686770.

- Uppal, S.K.; Beer, J.; Hadeler, E.; Gitlow, H.; Nouri, K. The Clinical Utility of Teledermoscopy in the Era of Telemedicine. Ther. 2021, 34, e14766. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14766.

- Day, W.G.; Shrivastava, V.; Roman, J.W. Synchronous Teledermoscopy in Military Treatment Facilities. Med. 2020, 185, e1334–e1337. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz479.

- Wang, R.H.; Barbieri, J.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Stavert, R.; Forman, H.P.; Bolognia, J.L.; Kovarik, C.L. Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Teledermatology: Where Are We Now and What Are the Barriers to Adoption? Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.065.

- Beer, J.; Hadeler, E.; Calume, A.; Gitlow, H.; Nouri, K. Teledermatology: Current Indications and Considerations for Future Use. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-020-02145-3.

- Pendlebury, G.A.; Oro, P.; Haynes, W.; Merideth, D.; Bartling, S.; Bongiorno, M.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Dermatological Conditions: A Novel, Comprehensive Review. Dermatopathology 2022, 9, 212–243. https://doi.org/10.3390/dermatopathology9030027.

- Woodley, A. Can Teledermatology Meet the Needs of the Remote and Rural Population? J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 574–579. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.10.574.

- Teledermatology from a Combat Zone | Dermatology | JAMA Dermatology | JAMA Network. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/209971 (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Giavina-Bianchi, M.; Santos, A.P.; Cordioli, E. Teledermatology Reduces Dermatology Referrals and Improves Access to Specialists. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29–30, 100641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100641.

- Veronese, F.; Branciforti, F.; Zavattaro, E.; Tarantino, V.; Romano, V.; Meiburger, K.M.; Salvi, M.; Seoni, S.; Savoia, P. The Role in Teledermoscopy of an Inexpensive and Easy-to-Use Smartphone Device for the Classification of Three Types of Skin Lesions Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11030451.

- Landow, S.M.; Oh, D.H.; Weinstock, M.A. Teledermatology Within the Veterans Health Administration, 2002–2014. e-Health 2015, 21, 769–773. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0225.

- Raugi, G.J.; Nelson, W.; Miethke, M.; Boyd, M.; Markham, C.; Dougall, B.; Bratten, D.; Comer, T. Teledermatology Implementation in a VHA Secondary Treatment Facility Improves Access to Face-to-Face Care. e-Health 2016, 22, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0036.

- Coates, S.J.; Kvedar, J.; Granstein, R.D. Teledermatology: From Historical Perspective to Emerging Techniques of the Modern Era: Part II: Emerging Technologies in Teledermatology, Limitations and Future Directions. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 577–586; quiz 587–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.014.

- Lipoff, J.B.; Cobos, G.; Kaddu, S.; Kovarik, C.L. The Africa Teledermatology Project: A Retrospective Case Review of 1229 Consultations from Sub-Saharan Africa. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 1084–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1119.

- Börve, A.; Terstappen, K.; Sandberg, C.; Paoli, J. Mobile Teledermoscopy—There’s an App for That! Pract. Concept. 2013, 3, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.0302a05.

- Lee, K.J.; Finnane, A.; Soyer, H.P. Recent Trends in Teledermatology and Teledermoscopy. Pract. Concept. 2018, 8, 214–223. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.0803a13.

- Tan, E.; Yung, A.; Jameson, M.; Oakley, A.; Rademaker, M. Successful Triage of Patients Referred to a Skin Lesion Clinic Using Teledermoscopy (IMAGE IT Trial). J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 803–811. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09673.x.

- Altayeb, A.; Dawood, S.; Atwan, A.; Mills, C. Teledermoscopy: A Helpful Detection Tool for Amelanotic and Hypomelanotic Melanoma. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 1244–1245. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20609.

- Bauer, J.; Blum, A.; Strohhäcker, U.; Garbe, C. Surveillance of Patients at High Risk for Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma Using Digital Dermoscopy. J. Dermatol. 2005, 152, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06370.x.

- Bandic, J.; Kovacevic, S.; Karabeg, R.; Lazarov, A.; Opric, D. Teledermoscopy for Skin Cancer Prevention: A Comparative Study of Clinical and Teledermoscopic Diagnosis. Acta Inform Med 2020, 28, 37–41, doi:10.5455/aim.2020.28.37-41.

- Snoswell, C.L.; Caffery, L.J.; Whitty, J.A.; Soyer, H.P.; Gordon, L.G. Cost-Effectiveness of Skin Cancer Referral and Consultation Using Teledermoscopy in Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0855.

- Wootton, R.; Bloomer, S.E.; Corbett, R.; Eedy, D.J.; Hicks, N.; Lotery, H.E.; Mathews, C.; Paisley, J.; Steele, K.; Loane, M.A. Multicentre Randomised Control Trial Comparing Real Time Teledermatology with Conventional Outpatient Dermatological Care: Societal Cost-Benefit Analysis. BMJ 2000, 320, 1252–1256. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1252.

- Naka, F.; Lu, J.; Porto, A.; Villagra, J.; Wu, Z.H.; Anderson, D. Impact of Dermatology EConsults on Access to Care and Skin Cancer Screening in Underserved Populations: A Model for Teledermatology Services in Community Health Centers. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.017.

- Lowe, A.; Atwan, A.; Mills, C. Teledermoscopy as a Community Based Diagnostic Test in the Era of COVID-19? Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 173–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.14399.

- Coustasse, A.; Sarkar, R.; Abodunde, B.; Metzger, B.J.; Slater, C.M. Use of Teledermatology to Improve Dermatological Access in Rural Areas. e-Health 2019, 25, 1022–1032. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0130.

- Loh, C.H.; Chong Tam, S.Y.; Oh, C.C. Teledermatology in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. JAAD Int. 2021, 5, 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdin.2021.07.007.

- Recognizing Monkeypox. Available online: https://www.aad.org/member/clinical-quality/clinical-care/monkeypox (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Number of Monkeypox Cases in the Military Climbs Tenfold in Less than 4 Weeks | Military.Com. Available online: https://www.military.com/daily-news/2022/08/05/number-of-monkeypox-cases-military-climbs-tenfold-less-4-weeks.html (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- CDC Monkeypox in the U.S. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/monitoring.html (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Clark, J.J.; Snyder, A.M.; Sreekantaswamy, S.A.; Petersen, M.J.; Lewis, B.K.H.; Secrest, A.M.; Florell, S.R. Dermatologic Care of Incarcerated Patients: A Single-Center Descriptive Study of Teledermatology and Face-to-Face Encounters. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 1660–1662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.076.

- Norton, S.A.; Burdick, A.E.; Phillips, C.M.; Berman, B. Teledermatology and Underserved Populations. Dermatol. 1997, 133, 197–200.

- GTP (v5.0)—Login. Available online: https://help.nmcp.med.navy.mil/path/user/ViewLogin.action (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Defense Health Agency. PATH & HELP to Transition to GTP; Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://path.tamc.amedd.army.mil/path/pdf/GTP_Transition2.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Reynolds, N. “Defense Health Agency (DHA) Update on Virtual Health (VH) for Defense Health Board” Presentation, Virtual. 30 March 2022. Available online: https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Meeting-References/2022/03/30/Defense-Health-Agency-Update-on-Virtual-Health (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Holmes, G.A.; Vassantachart, J.M.; Limone, B.A.; Zumwalt, M.; Hirokane, J.; Jacob, S.E. Using Dermoscopy to Identify Melanoma and Improve Diagnostic Discrimination. Pract. 2018, 35, S39–S45.

- Gall, R.; Bongiorno, M.; Handfield, K. Skin Cancer in the US Military. Cutis 2021, 107, 29–33. https://doi.org/10.12788/cutis.0153.

- Powers, J.G.; Patel, N.A.; Powers, E.M.; Mayer, J.E.; Stricklin, G.P.; Geller, A.C. Skin Cancer Risk Factors and Preventative Behaviors among United States Military Veterans Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 2871–2873. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.238.

- Riemenschneider, K.; Liu, J.; Powers, J.G. Skin Cancer in the Military: A Systematic Review of Melanoma and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Incidence, Prevention, and Screening among Active Duty and Veteran Personnel. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062.