Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Dean Liu and Version 1 by Joanna Kazimierowicz.

The aerobic granular sludge (AGS) method, which has been developed for several years, may represent an alternative to traditional technologies. One of the barriers to AGS deployment is the limited knowledge on the determinants and efficiency of the anaerobic digestion (AD) of AGS, as little research has been devoted to it.

- aerobic granular sludge

- anaerobic digestion

- wastewater treatment

- biogas

1. Introduction

The ever-more stringent quality standards for wastewater treatment effluents call for the development and deployment of efficient, commercially viable, and environmentally friendly wastewater treatment methods [1,2][1][2]. These criteria are largely met by established methods for microbial biodegradation and removal of pollutants, whether via conventional activated sludge (CAS) suspended in the wastewater or biofilm deposited on packing elements [3,4][3][4]. Nevertheless, in many cases, these technologies can be substituted with the aerobic granular sludge (AGS) method, which has been developed for several years [5,6][5][6]. Cases in which the implementation of AGS technology should be considered include the following possibilities: simplifying the technology by resigning from a multi-reactor sewage treatment line [7], changing the qualitative characteristics of the sewage flowing into the treatment plant to which AGS is relatively resistant [8], shortening the work cycle reactors [9], elimination of variable oxygen conditions in order to remove biogenic compounds [10], resignation from sludge separation devices [11], shortening the sedimentation phase [12], resignation from the system of recirculation pumps and agitators [13], reducing energy consumption [14].

AGS sewage treatment systems are now widely accepted as promising and forward- looking solutions due to their high technical readiness level, optimized processes for cultivating stable granules, as well as established and verified pollutant biodegradation parameters [15]. AGS has a number of clear advantages over CAS. These include, in particular: versatility, well-established treatment performance across different types of effluent, better and faster pollutant removal, improved settleability (and, thus, shorter retention times in AGS separation systems), and reduced bioreactor area/size [16]. This translates to lower investment and operating costs for wastewater treatment, bolstering the commercial competitiveness of AGS technology. Given these benefits, as well as the processing advantages, it is no wonder that AGS has been growing in popularity among researchers and municipal plant operators [9]. The method has been proven to be effective in full-scale systems for municipal/urban wastewater treatment, as well in biodegradation of various industrial pollutants. Large-scale systems have been designed and commissioned all around the world in Nereda® technology (Royal HaskoningDHV, Amersfoort, The Netherlands) [17,18][17][18].

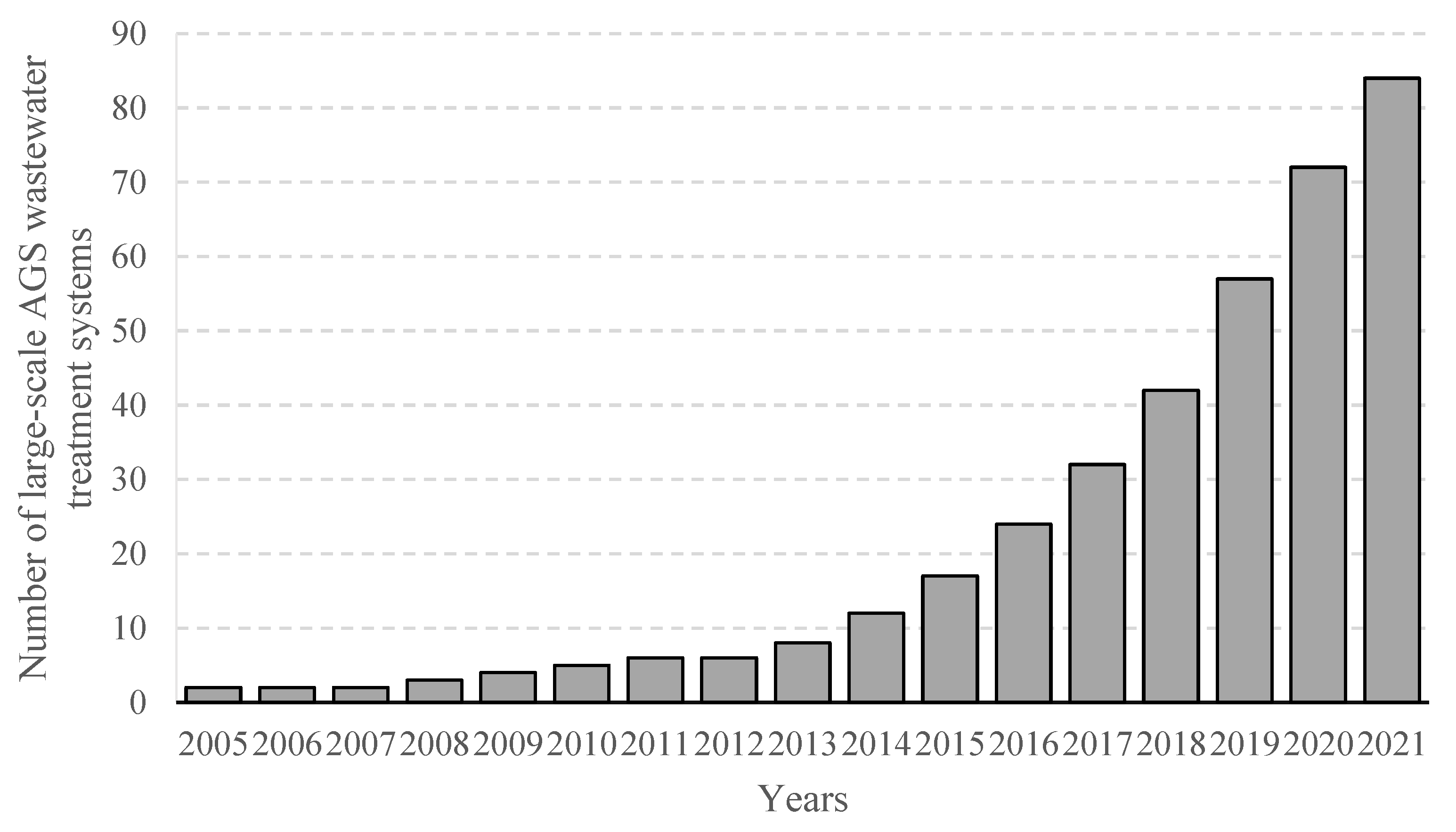

Recent years have seen a rapid spread of AGS wastewater treatment systems, which help identify and fully explore the strengths of the technology, as well as find solutions to existing technical issues and emergent operational hurdles [19]. By mid-2021, the number of AGS wastewater treatment plants was close to 90 facilities, meaning that it had more than doubled since 2018 [20]. The facilities ranged from 100 to 600,000 m3 in size and were designed primarily for full biodegradation of organic matter or nitrogen/phosphorus removal from household sewage and from mixed household–industrial sewage [21]. An analysis of data provided by AGS-deploying companies shows there were 13 new full-scale wastewater treatment plants being constructed and commissioned in 2020–2021. A further 11 are being discussed and designed, to be commissioned by 2025 [21], which speaks to the rapidly growing take-up of the technology. Many commissioned AGS installations are actually retrofitted CAS systems, modified to improve pollutant removal and ensure compliance with stringent quality requirements for wastewater-treatment effluent [22]. The number of full-scale AGS installations is provided in Figure 1 [21].

Figure 1. Worldwide number of large-scale AGS wastewater treatment systems from 2005 to 2021.

AGS is an advanced, optimized and well-explored technology incorporated into numerous large-scale installations. Nevertheless, it does have certain well-documented drawbacks that preclude its large-scale deployment and take-up. Researchers and operators have reported issues with granulated biomass instability, especially at longer running times [23,24][23][24]. This very often leads to diminished performance of AGS-separation systems, and may also cause the plant effluent to become re-contaminated with the dispersed bacterial suspension. This also leads to higher levels of pollutants detected during the treatment process [25].

Another barrier to the competitiveness of AGS is the limited knowledge on how to manage and, ultimately, neutralize the resultant surplus sludge. One of the most popular ways of militating or fully eliminating the nuisance-inducing sludge is by using anaerobic digestion (AD) [26]. This is a very well explored technology, commonly used as one of the steps in CAS processing to stabilize sludge, remove organic matter, reduce sludge volume, improve dewaterability, reduce sanitary indicators, limit nuisance smells, improve fertilizing properties and capture methane-rich biogas [27]. Due to the different properties and characteristics of AGS, the processes currently in use need to be tested for suitability and effectiveness in anaerobic treatment of sewage sludge. This means that the underpinnings and technological parameters of the AD process need to be validated and adapted to a substrate with a different chemical composition and properties. Relatively little research to date has focused on analyzing and optimizing anaerobic digestion of AGS, so there is a real need to review the existing findings and find prospective avenues for future research and practical efforts that could further ourthe scientific understanding and practical applicability of the process.

2. AGS Characteristics and Applications

AGS, as defined by the International Water Association (IWA), is made up of aggregates of microbial origin, which do not coagulate under reduced hydrodynamic shear, and which settle significantly faster than activated sludge flocs [28]. AGS granules are spherical or elliptical in shape. Their morphology is determined by the technological parameters of the wastewater treatment process (Table 1), including the pollutant load, the age of the sludge, the intensity of aeration and stirring, the type of feedstock, as well as any alternations to the design and operation cycle of the biological reactor [29]. The influence of operating conditions on the AGS characteristics, as well as graphics and photos of granules, have been presented in many scientific publications [30,31,32][30][31][32].Table 1. The influence of operating conditions on AGS characteristics.

| Operating Conditions | Impacts on Granulation Process | References |

|---|

Table 4. Examples of full-scale AGS wastewater treatment systems.

| Location | Start-Up | Flow Rate [m3/d] |

Wastewater | Removal Efficiency [%] |

Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additives Metal Cations | Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe2+/Fe3+ intensify granulation by neutralizing negatively charged sludge particles and enhancing adsorption/bridging interactions. | [23,33][23][33] | ||||||||

| Deodoro, Brazil | 2016 | Phase I—64,800 Phase II—86,400 | TP: 9.9 | Municipal[ | COD: >90; TN: >60; TP: >5079] |

[39,90][39][90] | ||||

| Aerobic starvation | Granulation is initiated by the lack of nutrients, increasing shear force and an increase in the hydrophobicity of the bacteria. | [34] | ||||||||

| Household wastewater | COD: 506; BOD | |||||||||

| Epe, Netherlands | 5: 224; TN: 49.4; AN: 39 TP: 6.7; |

Two SBR tanks with height of 7.5 m and working volume of 9600 m3 each; Cycle: 6.5 h in dry season, 3 h in rainy season; VER: 65% | 2011 | 8000 | Municipal and food-industry | COD: 96.9; BOD5: >99.4; TN: >94.7; AN: 99.8; TP: 97.2; total suspended solids (TSS): >98.5 |

[20,39,91][20] | Coagulant or inert carrier | Effect on the neutralization of negatively charged particles, which promotes aggregation and adsorption of the flocs. The large surface area of coagulants and inert carriers increases the granulation efficiency. | [21,33][21][33] |

| Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) | EPS aggregates bacterial cells and other solid particles to a granule precursor. The high content of EPS in the system allows the granules to withstand high values of hydraulic and pollutant loading. | [23,35][23][35] | ||||||||

| Food to microorganism F/M ratio | A high F/M ratio facilitates the formation of large granules. Finding the right F/M ratio is essential for achieving a fast and stable granulation. | [36,37][36][37] | ||||||||

| Hydraulic retention time (HRT) | Increasing HRT reduces OLR, which limits the granulation efficiency, hinders sedimentation and leads to a decrease in biomass concentration in the technological system, as well as the size and stability of granules. | [36,38][36][38] | ||||||||

| Hydrodynamic shear force | It regulates the growth of fibres, the porosity and density of the granules as well as the stability of granulation. Higher hydrodynamic shear provides better compaction and density of the granules. | [21,39][21][39] | ||||||||

| Organic loading rate (OLR) | High OLR allows for quick and efficient granulation, while delayed and difficult granulation formation was observed with low OLR. | [36,40][36][40] | ||||||||

| Seeding sludge | Type of seed pellets may contain cations and other properties that can help speed up the granulation process. It also acts as a nucleus that promotes the attraction of sludge flocs. | [21,33][21][33] | ||||||||

| Settling period | Removes poorly settling, flocculent sludge, enabling the deposition of appropriate granules and the selection of appropriate species of microorganisms. | [21,33][21][33] | ||||||||

| Sludge retention time SRT | Prolonged SRT causes deterioration of aerobic granulation, discharge of aging granular sludge and retention of appropriate newly synthesized granules is required for the stability of the aerobic granular sludge process, while shorter SRT results in a reduction of the size of the sludge flocs. | [4,37][4][37] | ||||||||

| Temperature | Granulation was successfully carried out in the temperature range of 8–30 °C. It was proven that low temperatures caused an increase in fiber content, causing leaching of bacterial cells and instability of granules. | [4,41][4][41] | ||||||||

| Volumetric exchange ratio | High volumetric exchange rates increase the granulation, facilitating the formation and improving the sedimentation properties of the granules. | [36,40][36][40] |

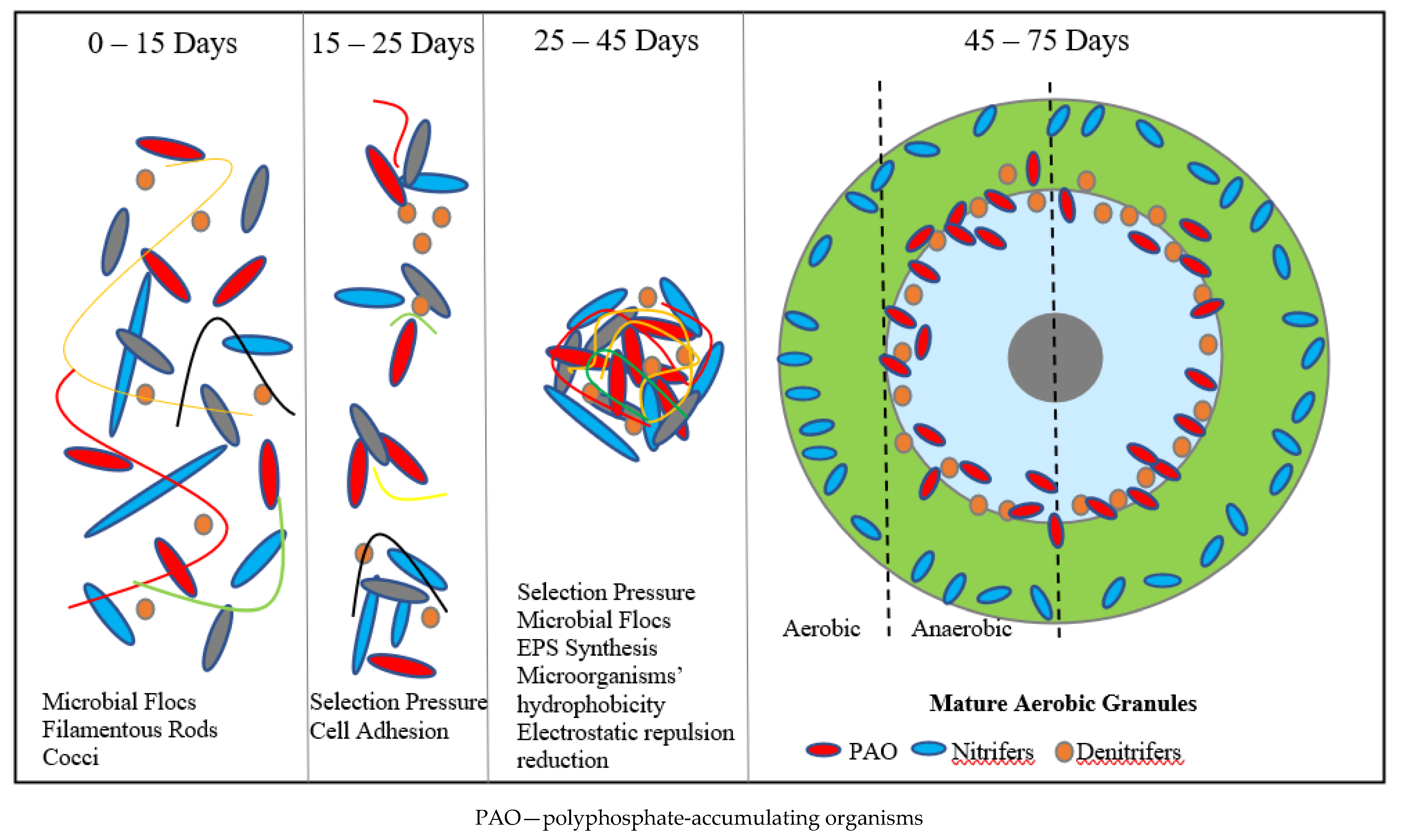

Figure 2. Illustrative chart of AGS granulation process.

Table 2. Comparison of AGS and CAS characteristics.

| Parameter | Unit | Value | Reference | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGS | CAS | |||||||||||||

| Shape | - | Compact and spherical granular structure | Irregular and flocculent structure | [39] | ||||||||||

| Size | μm | >200 | 50–300 | COD: 88; BOD5: 96; TN: 86; AN: 97;[41] |

||||||||||

| TP: 87 | COD: 60.7; | BOD5: 9; TN: 6.9; AN: 1.2; TP: 0.9 |

[13] | [39 | Settling velocity | m/h | 10–130 | 2–10 | ||||||

| ] | Household sewage (40%) + industrial wastewater (60%) | COD: 1000; AN: 60 | [ | 60] | ||||||||||

| [ | 91 | ] | SBR; Height: 100 cm and Diameter: 20 cm; Cycle period: 4 h; VER: 50% | COD: 80; | ||||||||||

| Gansbaai, South Africa | TN: 98 | COD: 200; | AN: 1.2 | 2009 | 4000 | Municipal (with a high proportion of industrial slaughterhouse effluent) | COD: 94; TN: 90; TP: >80[80] |

[39,90][39][90] | Specific gravity | - | 1.010–1.017 | 0.997–1.01 | [7] | |

| Livestock wastewater | COD: 3600; TN: 650; | |||||||||||||

| Garmerwolde, Netherlands | TP: 380 | 4 L SBR; Cycle period: 4 h; VER: 50%; 27–30 °C |

COD: 74; TN: 73; TP: 70 |

COD: 93.6; TN: 175.5; TP: 114 |

2013 | 30,000 | Municipal | COD: 89.2; BOD5: 96.0; TN: 86.0;[81] |

TP: 90.3; TSS: 96.4 |

[92] | 1.004–1.100 | 1.002–1.106 | [55] | |

| Palm oil mill effluents | COD: 69500; AN: 45 |

3 L SBR; Cycle period: 3 h; VER: 50% | ||||||||||||

| Kingaroy, Australia | 2016 | 2625 | COD: 91.1; AN: 97.6 |

COD: 69500; AN: 45 |

[82] | Municipal | COD: >90; TN: 95; TP: >90 |

[39,90][39][90 | Water content | % | ||||

| ] | Septic wastewater | COD: 971; AN: 80; TP: 19;94–97 |

99 |

SS: 670 | Three SBR tanks (7 m height) with maximum capacity of 5000 m3 d−1 | COD: 94; AN: 99; TP: 83.5; SS: 98[55] |

||||||||

| COD: 58.3; | ||||||||||||||

| Lubawa, Poland | 2017 | 3200 | AN: 0.8; | Mainly municipal, 30–40% dairy effluent TP: 3.1; SS: 13.4 |

COD: 97.0; BOD5: 98.2; TN: 87.0; AN: 99.4 TP: 95.4;[61] |

[93] | Sludge Volume Index | mL/g | ||||||

| Ryki, Poland | 2015 | |||||||||||||

| Slaughter house wastewater | COD: 1250 ± 150; AN: 120 ± 20; TP: 30 ± 5 |

20 L volume SBR; Cycle period: 6 h; VER: 50%; 18–22 °C | COD: 95.1; AN: 99.3; TP: 83.5 | [39,61][39][61] | ||||||||||

| COD: 6.1; | AN: 0.8; | TP: 5.0 | [83] | 5320 | Municipal | COD: >90; TN: >90; TP: >90 |

5 min | 30–60 | ||||||

| [ | 39 | , | 90 | ] | [39 | Rubber industry wastewater– | ||||||||

| ] | [ | 90 | ] | COD: 1850; TN: 248; AN: 49 |

0.6 L SBR; Cycle period: 3 h; VER: 50%; 27 ± 1 °C | COD: 96.5; TN: 89.4 AN: 94.7 |

COD: 64.75; TN: 2.6 AN: 94.7 |

[84] | 30 min | 30–60 | 110–160 | |||

| Synthetic wastewater with phenol | 200 | 1 L SBR, 12 h cycle, 2 cycles per day, 30 °C, 200 rpm | Redox microenvironments | - | Aerobic, anoxic, and anaerobic microbial layers | Minimum feasibility for anaerobic zones | [7,62][7][62] | |||||||

| EPS synthesis | - | High EPS content in aerobic granules as compared to CAS | Lower EPS content | [7,63][7][63] | ||||||||||

| OLR | - | Capable of withstanding high OLR | Poor removal performance at high OLR | [7,63][7][63] | ||||||||||

| Resistance to shock and fluctuating OLR | - | Able to remove pollutants under shock or fluctuating OLR | Poor removal under shock or fluctuating OLR | [7] | ||||||||||

| Tolerance to toxic compounds | - | Higher tolerance to toxic pollutants | Lower tolerance to toxic pollutants | [7,63][7][63] | ||||||||||

Table 3. Avenues of AGS use in wastewater treatment.

| Type of Sewage/Waste | Initial Concentration [mg/dm3] | Reactor Configuration and Operation Conditions | Removal Efficiency [%] | Final Concentration [mg/dm3] * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy wastewater | COD: 2800; TN: 40; TP: 30 |

12 L SBR; Cycle period: 8 h | COD: 90; TN: 80; TP: 67 |

COD: 28; TN: 8; | |

| Yancang, China | |||||

| 2008 | |||||

| 50,000 | |||||

| Urban (30% domestic sewage and 70% industrial wastewater from printing and dyeing, chemical, textile and beverage) | COD: 85; | TN: 59.6; | AN: 95.8 |

[22] | |

| 100 | - | [ | 85 | ] | |

| 1000 | 97 | 30 | |||

| Synthetic wastewater with p-Nitrophenol (PNP) | 200 | 1 L SBR, 75% VER; 24 h cycle with 23.5 h aeration, 1.6 cm/s SAV, 30 °C | 100 | - | [86] |

| Synthetic wastewater with 2,4-Dintrotoluene (2,4-DNT) | 10 | 1 L SBR, 70% VER; 24 h cycle with 23 h aeration, 1.2 cm/s SAV, 30 °C, 100 rpm | 90 | 1 | [87] |

AN—ammonia nitrogen, BOD5—biochemical oxygen demand, COD—chemical oxygen demand, rpm—rotation speed, SAV—superficial air velocity, SBR—sequencing biological reactor, TN—total nitrogen, TP—total phosphorus, VER—volumetric exchange ratio, * own calculations.

The first pilot AGS-growing plant was constructed in Ede (Netherlands) in 2003 and consisted of two parallel batch reactors with a volume of approx. 1.5 m3 [88]. Another pilot-scale installation for treating municipal wastewater was established at the Zhuzhuanjing sewage treatment plant in Hefei (China), consisting of two 1 m3 batch reactors [89]. The first aerobic-granule sewage treatment plant was commissioned in Gansbaai. It was designed for a 4000 m3/d flow capacity and consisted of three parallel batch reactors, 7 m high and 8 m in diameter. A full-scale aerobic-granule system also operates in Epe (Netherlands). The facility is supplied with municipal and food-industry effluent at 8000 m3/h [20,39][20][39]. Li et al. [22

References

- Hung, Y.T.; Aziz, H.A.; Al-Khatib, I.A.; Abdel Rahman, R.O.; Cora-Hernandez, M.G.R. Water Quality Engineering and Wastewater Treatment. Water 2021, 13, 330.

- Karolinczak, B.; Miłaszewski, R.; Dąbrowski, W. Cost Optimization of Wastewater and Septage Treatment Process. Energies 2020, 13, 6406.

- Waqas, S.; Bilad, M.R.; Man, Z.; Wibisono, Y.; Jaafar, J.; Indra Mahlia, T.M.; Khan, A.L.; Aslam, M. Recent Progress in Integrated Fixed-Film Activated Sludge Process for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110718.

- Wilén, B.M.; Liébana, R.; Persson, F.; Modin, O.; Hermansson, M. The Mechanisms of Granulation of Activated Sludge in Wastewater Treatment, Its Optimization, and Impact on Effluent Quality. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 5005–5020.

- Lettinga, G.; van Velsen, A.F.M.; Hobma, S.W.; de Zeeuw, W.; Klapwijk, A. Use of the Upflow Sludge Blanket (USB) Reactor Concept for Biological Wastewater Treatment, Especially for Anaerobic Treatment. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1980, 22, 699–734.

- Mishima, K.; Nakamura, M. Self-Immobilization of Aerobic Activated Sludge–A Pilot Study of the Aerobic Upflow Sludge Blanket Process in Municipal Sewage Treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 1991, 23, 981–990.

- Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Sarvajith, M. Aerobic Granular Sludge Process: A Fast Growing Biological Treatment for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2019, 12, 57–65.

- Calderón-Franco, D.; Sarelse, R.; Christou, S.; Pronk, M.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Abeel, T.; Weissbrodt, D.G. Metagenomic Profiling and Transfer Dynamics of Antibiotic Resistance Determinants in a Full-Scale Granular Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plant. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118571.

- Rosa-Masegosa, A.; Muñoz-Palazon, B.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Fenice, M.; Gorrasi, S.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J. New Advances in Aerobic Granular Sludge Technology Using Continuous Flow Reactors: Engineering and Microbiological Aspects. Water 2021, 13, 1792.

- Sarvajith, M.; Nancharaiah, Y.V. Enhancing Biological Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal Performance in Aerobic Granular Sludge Sequencing Batch Reactors by Activated Carbon Particles. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114134.

- Sarkar, G.S.; Rathi, A.; Basu, S.; Arya, R.K.; Halder, G.N.; Barman, S. Removal of Endocrine-Disrupting Compounds by Wastewater Treatment. In Advanced Industrial Wastewater Treatment and Reclamation of Water; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 129–151.

- Peng, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Fang, F.; Yan, P.; Liu, Z. Effect of Different Forms and Components of EPS on Sludge Aggregation during Granulation Process of Aerobic Granular Sludge. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 135116.

- Pronk, M.; de Kreuk, M.K.; de Bruin, B.; Kamminga, P.; Kleerebezem, R.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Full Scale Performance of the Aerobic Granular Sludge Process for Sewage Treatment. Water Res. 2015, 84, 207–217.

- Bengtsson, S.; de Blois, M.; Wilén, B.M.; Gustavsson, D. A Comparison of Aerobic Granular Sludge with Conventional and Compact Biological Treatment Technologies. Environ. Technol. 2018, 40, 2769–2778.

- Cai, F.; Lei, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. A Review of Aerobic Granular Sludge (AGS) Treating Recalcitrant Wastewater: Refractory Organics Removal Mechanism, Application and Prospect. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146852.

- Corsino, S.F.; Devlin, T.R.; Oleszkiewicz, J.A.; Torregrossa, M. Aerobic Granular Sludge: State of the Art, Applications, and New Perspectives. In Advances in Wastewater Treatment; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2019.

- Muñoz-Palazón, B.; Hurtado-Martinez, M.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J. Simultaneous Nitrification and Denitrification Processes in Granular Sludge Technology. In Nitrogen Cycle; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 222–244.

- Niermans, R.; Giesen, A.; van Loosdrecht, M.; de Bruin, B. Full-Scale Experiences with Aerobic Granular Biomass Technology for Treatment of Urban and Industrial Wastewater. In Proceedings of the 2014 Water Environment Federation, Austin, TX, USA, 18–21 May 2014; pp. 2347–2357.

- Campo, R.; Lubello, C.; Lotti, T.; Di Bella, G. Aerobic Granular Sludge–Membrane BioReactor (AGS–MBR) as a Novel Configuration for Wastewater Treatment and Fouling Mitigation: A Mini-Review. Membranes 2021, 11, 261.

- Sepúlveda-Mardones, M.; Campos, J.L.; Magrí, A.; Vidal, G. Moving Forward in the Use of Aerobic Granular Sludge for Municipal Wastewater Treatment: An Overview. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2019, 18, 741–769.

- Hamza, R.; Rabii, A.; Ezzahraoui, F.Z.; Morgan, G.; Iorhemen, O.T. A Review of the State of Development of Aerobic Granular Sludge Technology over the Last 20 Years: Full-Scale Applications and Resource Recovery. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 5, 100173.

- Li, J.; Ding, L.B.; Cai, A.; Huang, G.X.; Horn, H. Aerobic Sludge Granulation in a Full-Scale Sequencing Batch Reactor. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 268789.

- Lin, H.; Ma, R.; Hu, Y.; Lin, J.; Sun, S.; Jiang, J.; Li, T.; Liao, Q.; Luo, J. Reviewing Bottlenecks in Aerobic Granular Sludge Technology: Slow Granulation and Low Granular Stability. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114638.

- Yin, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Sun, J. Overcoming the Instability of Aerobic Granular Sludge under Nitrogen Deficiency through Shortening Settling Time. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121620.

- Leal, C.; Val del Río, A.; Mesquita, D.P.; Amaral, A.L.; Castro, P.M.L.; Ferreira, E.C. Sludge Volume Index and Suspended Solids Estimation of Mature Aerobic Granular Sludge by Quantitative Image Analysis and Chemometric Tools. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 234, 116049.

- Zielinski, M.; Debowski, M.; Kazimierowicz, J. The Effect of Static Magnetic Field on Methanogenesis in the Anaerobic Digestion of Municipal Sewage Sludge. Energies 2021, 14, 590.

- Hidaka, T.; Tsushima, I.; Tsumori, J. Comparative Analyses of Microbial Structures and Gene Copy Numbers in the Anaerobic Digestion of Various Types of Sewage Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 253, 315–322.

- De Kreuk, M.K.; McSwain, B.S.; Bathe, S.; Tay, J.; Schwarzenbeck, S.T.L.; Wilderer, P.A. Discussion Outcomes. In Aerobic Granular Sludge, Water and Environmental Management Series; IWA Publishing: Munich, Germany, 2005; pp. 165–169.

- Xiao, X.; Ma, F.; You, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, J.; Bao, X.; Ma, X. Direct Sludge Granulation by Applying Mycelial Pellets in Continuous-Flow Aerobic Membrane Bioreactor: Performance, Granulation Process and Mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126233.

- Amin Vieira da Costa, N.P.; Libardi, N.; Ribeiro da Costa, R.H. How Can the Addition of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS)-Based Bioflocculant Affect Aerobic Granular Sludge (AGS)? J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114807.

- Pishgar, R.; Dominic, J.A.; Sheng, Z.; Tay, J.H. Influence of Operation Mode and Wastewater Strength on Aerobic Granulation at Pilot Scale: Startup Period, Granular Sludge Characteristics, and Effluent Quality. Water Res. 2019, 160, 81–96.

- Wagner, J.; Weissbrodt, D.G.; Manguin, V.; Ribeiro da Costa, R.H.; Morgenroth, E.; Derlon, N. Effect of Particulate Organic Substrate on Aerobic Granulation and Operating Conditions of Sequencing Batch Reactors. Water Res. 2015, 85, 158–166.

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.; Nuramkhaan, M.; Lei, Z.; Shimizu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Adachi, Y.; Lee, D.J.; Tay, J.H. Rapid Granulation of Aerobic Granular Sludge: A Mini Review on Operation Strategies and Comparative Analysis. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100206.

- Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Kiran Kumar Reddy, G. Aerobic Granular Sludge Technology: Mechanisms of Granulation and Biotechnological Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1128–1143.

- Zhou, J.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L. Influences of Extracellular Polymeric Substances on the Dewaterability of Sewage Sludge during Bioleaching. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102688.

- Khan, M.Z.; Mondal, P.K.; Sabir, S. Aerobic Granulation for Wastewater Bioremediation: A Review. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 91, 1045–1058.

- de Sousa Rollemberg, S.L.; Mendes Barros, A.R.; Milen Firmino, P.I.; Bezerra dos Santos, A. Aerobic Granular Sludge: Cultivation Parameters and Removal Mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 270, 678–688.

- Bengtsson, S.; de Blois, M.; Wilén, B.M.; Gustavsson, D. Treatment of Municipal Wastewater with Aerobic Granular Sludge. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 48, 119–166.

- Pronk, M.; Giesen, A.; Thompson, A.; Robertson, S.; Van Loosdrecht, M. Aerobic Granular Biomass Technology: Advancements in Design, Applications and Further Developments. Water Pract. Technol. 2017, 12, 987–996.

- Lee, D.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Show, K.Y.; Whiteley, C.G.; Tay, J.H. Advances in Aerobic Granule Formation and Granule Stability in the Course of Storage and Reactor Operation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 919–934.

- Franca, R.D.G.; Pinheiro, H.M.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Lourenço, N.D. Stability of Aerobic Granules during Long-Term Bioreactor Operation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 228–246.

- Han, X.; Jin, Y.; Yu, J. Rapid Formation of Aerobic Granular Sludge by Bioaugmentation Technology: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 437, 134971.

- Bassin, J.P. Aerobic Granular Sludge Technology. In Advanced Biological Processes for Wastewater Treatment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 75–142.

- Dulekgurgen, E.; Artan, N.; Orhon, D.; Wilderer, P.A. How Does Shear Affect Aggregation in Granular Sludge Sequencing Batch Reactors? Relations between Shear, Hydrophobicity, and Extracellular Polymeric Substances. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 58, 267–276.

- Wang, Z.W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.Q.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Short-Term Starvation on Aerobic Granules. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 2373–2378.

- Liu, Y.; Yang, S.F.; Tay, J.H. Improved Stability of Aerobic Granules by Selecting Slow-Growing Nitrifying Bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 108, 161–169.

- Guo, F.; Zhang, S.H.; Yu, X.; Wei, B. Variations of Both Bacterial Community and Extracellular Polymers: The Inducements of Increase of Cell Hydrophobicity from Biofloc to Aerobic Granule Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 6421–6428.

- Liu, X.; Pei, Q.; Han, H.; Yin, H.; Chen, M.; Guo, C.; Li, J.; Qiu, H. Functional Analysis of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) during the Granulation of Aerobic Sludge: Relationship among EPS, Granulation and Nutrients Removal. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112692.

- Zhang, B.; Lens, P.N.L.; Shi, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Bao, X.; Cui, F. Enhancement of Aerobic Granulation and Nutrient Removal by an Algal–Bacterial Consortium in a Lab-Scale Photobioreactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2373–2382.

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Wan, C. Understanding the Role of Cations and Hydrogen Bonds on the Stability of Aerobic Granules from the Perspective of the Aggregation and Adhesion Behavior of Extracellular Polymeric Substances. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148659.

- Zou, J.; Yu, F.; Pan, J.; Pan, B.; Wu, S.; Qian, M.; Li, J. Rapid Start-up of an Aerobic Granular Sludge System for Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal through Seeding Chitosan-Based Sludge Aggregates. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 144171.

- Karakas, I.; Sam, S.B.; Cetin, E.; Dulekgurgen, E.; Yilmaz, G. Resource Recovery from an Aerobic Granular Sludge Process Treating Domestic Wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 34, 101148.

- Moura, L.L.; Duarte, K.L.S.; Santiago, E.P.; Mahler, C.F.; Bassin, J.P. Strategies to Re-Establish Stable Granulation after Filamentous Outgrowth: Insights from Lab-Scale Experiments. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 606–615.

- Ouyang, L.; Huang, W.; Huang, M.; Qiu, B. Polyaniline Improves Granulation and Stability of Aerobic Granular Sludge. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 1, 1–11.

- Lashkarizadeh, M. Operating pH and Feed Composition as Factors Affecting Stability of Aerobic Granular Sludge. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2015.

- Franca, R.D.G.; Pinheiro, H.M.; Lourenço, N.D. Recent Developments in Textile Wastewater Biotreatment: Dye Metabolite Fate, Aerobic Granular Sludge Systems and Engineered Nanoparticles. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2020, 19, 149–190.

- Stes, H.; Caluwé, M.; Dockx, L.; Cornelissen, R.; de Langhe, P.; Smets, I.; Dries, J. Cultivation of Aerobic Granular Sludge for the Treatment of Food-Processing Wastewater and the Impact on Membrane Filtration Properties. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 39–51.

- Tavares Ferreira, T.J.; Luiz de Sousa Rollemberg, S.; Nascimento de Barros, A.; Machado de Lima, J.P.; Bezerra dos Santos, A. Integrated Review of Resource Recovery on Aerobic Granular Sludge Systems: Possibilities and Challenges for the Application of the Biorefinery Concept. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 291, 112718.

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Yuan, S.-C.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Yuan, S.-C. Reactivation of Hypersaline Aerobic Granular Sludge after Low-Temperature Storage. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2017, 8, 61–70.

- Muñoz-Palazón, B. Biological and Technical Study of Aerobic Granular Sludge Systems for Treating Urban Wastewater Effect of Temperature. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2020.

- Giesen, A.; de Bruin, L.M.M.; Niermans, R.P.; van der Roest, H.F. Advancements in the Application of Aerobic Granular Biomass Technology for Sustainable Treatment of Wastewater. Water Pract. Technol. 2013, 8, 47–54.

- Dall’Agnol, P.; Libardi, N.; Muller, J.M.; Xavier, J.A.; Domingos, D.G.; Da Costa, R.H.R. A Comparative Study of Phosphorus Removal Using Biopolymer from Aerobic Granular Sludge: A Factorial Experimental Evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103541.

- Ladnorg, S.; Junior, N.L.; Dall’Agnol, P.; Domingos, D.G.; Magnus, B.S.; Wichern, M.; Gehring, T.; Da Costa, R.H.R. Alginate-like Exopolysaccharide Extracted from Aerobic Granular Sludge as Biosorbent for Methylene Blue: Thermodynamic, Kinetic and Isotherm Studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103081.

- Lemaire, R.; Yuan, Z.; Blackall, L.L.; Crocetti, G.R. Microbial Distribution of Accumulibacter Spp. and Competibacter Spp. in Aerobic Granules from a Lab-Scale Biological Nutrient Removal System. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 354–363.

- Tay, J.H.; Liu, Q.S.; Liu, Y. The Effects of Shear Force on the Formation, Structure and Metabolism of Aerobic Granules. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 57, 227–233.

- Weber, S.D.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.H.; Fried, J. Microbial Composition and Structure of Aerobic Granular Sewage Biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 6233–6240.

- Song, Z.; Ren, N.; Zhang, K.; Tong, L. Influence of Temperature on the Characteristics of Aerobic Granulation in Sequencing Batch Airlift Reactors. J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 21, 273–278.

- Lee, S.; Basu, S.; Tyler, C.; Pitt, P.A. A Survey of Filamentous Organisms at the Deer Island Treatment Plant. Env. Technol. 2008, 24, 855–865.

- Rossetti, S.; Tomei, M.C.; Nielsen, P.H.; Tandoi, V. “Microthrix Parvicella”, a Filamentous Bacterium Causing Bulking and Foaming in Activated Sludge Systems: A Review of Current Knowledge. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 49–64.

- Shi, X.Y.; Yu, H.Q.; Sun, Y.J.; Huang, X. Characteristics of Aerobic Granules Rich in Autotrophic Ammonium-Oxidizing Bacteria in a Sequencing Batch Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 147, 102–109.

- Kim, D.J.; Seo, D. Selective Enrichment and Granulation of Ammonia Oxidizers in a Sequencing Batch Airlift Reactor. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 1055–1062.

- Al-Hashimi, M.A.I.; Abbas, T.R.; Jumaha, G.F. Aerobic Granular Sludge: An Advanced Technology to Treat Oil Refinery and Dairy Wastewaters. Eng. Technol. J. 2017, 35, 216–221.

- Bumbac, C.; Ionescu, I.A.; Tiron, O.; Badescu, V.R. Continuous Flow Aerobic Granular Sludge Reactor for Dairy Wastewater Treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 71, 440–445.

- Ren, Y.; Ferraz, F.M.; Yuan, Q. Landfill Leachate Treatment Using Aerobic Granular Sludge. J. Environ. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017060.

- Ho, K.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lin, B.; Lee, D.J. Degrading High-Strength Phenol Using Aerobic Granular Sludge. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 2009–2015.

- Carucci, A.; Milia, S.; De Gioannis, G.; Piredda, M. Acetate-Fed Aerobic Granular Sludge for the Degradation of 4-Chlorophenol. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 483–490.

- Wang, S.G.; Liu, X.W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Gong, W.X.; Sun, X.F.; Gao, B.Y. Aerobic Granulation for 2,4-Dichlorophenol Biodegradation in a Sequencing Batch Reactor. Chemosphere 2007, 69, 769–775.

- Zhang, L.L.; Chen, J.M.; Fang, F. Biodegradation of Methyl T-Butyl Ether by Aerobic Granules under a Cosubstrate Condition. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 78, 543–550.

- Schwarzenbeck, N.; Borges, J.M.; Wilderer, P.A. Treatment of Dairy Effluents in an Aerobic Granular Sludge Sequencing Batch Reactor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 66, 711–718.

- Liu, Y.Q.; Moy, B.; Kong, Y.H.; Tay, J.H. Formation, Physical Characteristics and Microbial Community Structure of Aerobic Granules in a Pilot-Scale Sequencing Batch Reactor for Real Wastewater Treatment. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2010, 46, 520–525.

- Othman, I.; Anuar, A.N.; Ujang, Z.; Rosman, N.H.; Harun, H.; Chelliapan, S. Livestock Wastewater Treatment Using Aerobic Granular Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 133, 630–634.

- Abdullah, N.; Ujang, Z.; Yahya, A. Aerobic Granular Sludge Formation for High Strength Agro-Based Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 6778–6781.

- Liu, Y.; Kang, X.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y. Performance of Aerobic Granular Sludge in a Sequencing Batch Bioreactor for Slaughterhouse Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 190, 487–491.

- Rosman, N.H.; Nor Anuar, A.; Othman, I.; Harun, H.; Sulong, M.Z.; Elias, S.H.; Mat Hassan, M.A.H.; Chelliapan, S.; Ujang, Z. Cultivation of Aerobic Granular Sludge for Rubber Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 129, 620–623.

- Adav, S.S.; Chen, M.Y.; Lee, D.J.; Ren, N.Q. Degradation of Phenol by Aerobic Granules and Isolated Yeast Candida Tropicalis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 96, 844–852.

- Suja, E.; Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Venugopalan, V.P. P-Nitrophenol Biodegradation by Aerobic Microbial Granules. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 167, 1569–1577.

- Kiran Kumar Reddy, G.; Sarvajith, M.; Nancharaiah, Y.V.; Venugopalan, V.P. 2,4-Dinitrotoluene Removal in Aerobic Granular Biomass Sequencing Batch Reactors. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2017, 119, 56–65.

- De Kreuk, M.K.; Kishida, N.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Aerobic Granular Sludge—State of the Art. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 75–81.

- Ni, B.J.; Xie, W.M.; Liu, S.G.; Yu, H.Q.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, G.; Dai, X.L. Granulation of Activated Sludge in a Pilot-Scale Sequencing Batch Reactor for the Treatment of Low-Strength Municipal Wastewater. Water Res. 2009, 43, 751–761.

- Luiz De Souza Rollemberg, S.; Queiroz De Oliveira, L.; Igor, P.; Firmino, M.; Bezerra, A.; Santos, D. Aerobic Granular Sludge Technology in Domestic Wastewater Treatment: Opportunities and Challenges. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2020, 25, 439–449.

- Bay Area Clean Water Agencies (BACWA)—AECOM. Nereda® Aerobic Granular Sludge Demonstration. 2017. Available online: https://bacwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/BACWA-AECOM-March-17th-2017-Nereda-Demonstration-Opportunity-3.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2022).

- Guo, H.; van Lier, J.B.; de Kreuk, M. Digestibility of Waste Aerobic Granular Sludge from a Full-Scale Municipal Wastewater Treatment System. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115617.

- Świątczak, P.; Cydzik-Kwiatkowska, A. Performance and Microbial Characteristics of Biomass in a Full-Scale Aerobic Granular Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1655–1669.

More