Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Fanzhi Jiang and Version 1 by Fanzhi Jiang.

最近的研究表明,算法音乐之所以引起全球关注,不仅因为它的娱乐性,还因为它在行业中的巨大潜力。因此,产量增加了在算法音乐生成主题上旋转的学术数字。数理逻辑和美学价值之间的平衡在音乐的产生中很重要。Recent studies demonstrate that algorithmic music attracted global attention not only because of its amusement but also its considerable potential in the industry. Thus, the yield increased academic numbers spinning around on topics of algorithm music generation. The balance between mathematical logic and aesthetic value is important in music generation.

- music generation

- pentatonic scale

- clustering

1. Introduction

During the past few decades, the field of computer music has precisely addressed challenges surrounding the analysis of musical concepts [1,2]. Indeed, only by first understanding this type of information can we provide more advanced analytical and compositional tools, as well as methods to advance music theory [2]. Currently, literature on music computing and intelligent creativity [1,3,4] focuses specifically on algorithmic music. We have observed a notable rise in literature inspired by the field of machine learning because of its attempt to explain the compositional textures and formation methods within music on a mathematical level [5,6]. Machine learning methods are well accepted as an additional motivation for generating music content. Instead of the previous methods, such as grammar-based [1], rule-based [7], and metaheuristic strategy-based [8] music generation systems, machine learning-based generation methods can learn musical paradigms from an arbitrary corpus. Thus, the same system can be used for various musical genres.

Driven by the requirement for widespread music content, more massive music datasets have emerged in the genres of classical [9], rock [10], and pop music [11], for instance. However, a publicly available corpus of traditional folk music seems to pay little attention to the niche corner. Historically, research investigating factors associated with music composition from large-scale music datasets has focused on deep learning architectures, stemming from its ability to automatically learn musical styles from a corpus and generate new content [5].

Although music possesses its special characteristics that distinguish it from text, it is still classified as sequential data because of its temporal sequential relationship. Hence, recurrent neural networks (RNN) and its variants are adopted by most music-generating neural network models that are currently available [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Music generation sequence models were often characterized by the representation and prediction of a number of events. Then, those models can use the conditions formed by previous events to generate the current event. MelodyRNN [18] and SampleRNN [19] are representatives of this approach, with the shortcoming that the generated music lacks segmental integrity and a musical recurrent structure. Neural networks have studied this musical repetitive structure, called translation invariance [20]. Convolutional neural network (CNN) has been influential in the music domain, stemming from its excellence in the image domain. This regional learning capability is sought to migrate to the translational invariance of the musical context. Some representative work has emerged [21,22,23] to use deep CNN for music generation, although there have been few attempts. However, it seems to be more imitative than creative in music, stemming from its over-learning of the local structure of music. Therefore, inspired by whether it is possible to combine the advantages of both structures, they used compound architectures in music generation research [12,24,25,26].

Compound architecture combines at least two architectures of the same type or of different types [5] and can be divided into two main categories. Some cases are homogeneous composite architectures that combine various instances of the same architecture, such as the stacked autoencoder. Most cases are heterogeneous compound architectures that combine various types of architectures, such as a RNN Encoder-Decoder that combines the RNN and autoencoder. From an architectural point of view, we can conduct compositing using different methodologies.

- 。这部作品

- -based music generation. This work [12]是一种 is an RNN架构,具有循环层的层次结构,不仅可以生成旋律,还可以生成鼓和和弦。该模型 architecture with a hierarchy of cyclic layers that generates not only melodies but also drums and chords. The model [13]很好地证明了 well demonstrates the ability of RNN同时生成多个序列的能力。但是,它需要预先了解音阶和旋律的一些轮廓才能生成。结果表明,基于文本的长短期记忆(LSTM)在生成和弦和鼓时表现更好。s to generate multiple sequences at the same time. However, it requires prior knowledge of the scale and some contours of the melody to be generated. The results demonstrate that the text-based Long short-term Memory (LSTM) performs better in generating chords and drums. MelodyRNN [18]可能是神经网络在符号域中生成音乐的最著名的例子之一。它包括该模型的三个基于 is probably one of the best-known examples of neural networks generating music in the symbolic domain. It includes three RNN的变体,两个旨在音乐结构学习的变体,回顾RNN和注意力RNN。索尼-based variants of the model, two variants aimed at musical structure learning, lookback RNN and Attention RNN. Sony CSL [31]提出了 proposed DeepBach,它可以专门创作出J.S.巴赫风格的复调四部分合唱曲目。它也是一个基于RNN的模型,允许执行用户定义的约束,例如节奏,音符,部分,和弦和快板。然而,由于以下原因,这个方向仍然具有挑战性。从外部看,整体音乐结构似乎没有层次特征,部分也没有统一的节奏模式。音乐特征在音乐语法方面被认为是极其简化的,忽略了关键的音乐特征,如音符时间,节奏,音阶和间隔。关于音乐的内涵,音乐风格是不可控的,审美测量是无效的,听觉与音乐家创作的音乐之间存在着明显的差距。, which could specifically compose a polyphonic four-part choral repertoire in the style of J. S. Bach. It is also an RNN-based model that allows the execution of user-defined constraints, such as rhythms, notes, parts, chords, and allegro. However, this direction remains challenging for the following reasons. From the outside, the overall musical structure seems to have no hierarchical features, and parts do not have a unified rhythmic pattern. Musical features are considered extremely simplified in terms of musical grammar, ignoring key musical features such as note timing, tempo, scale, and interval. Regarding the connotation of music, the music style is uncontrollable, the aesthetic measurement is invalid, and there is a significant gap between the sense of hearing and the music created by the musicians.

-

基于 CNN 的音乐生成。一些-based music generation. Some CNN 架构已被确定为architectures have been identified as an alternative to RNN 架构的替代方案architectures [21,,22]。本文. The paper [21]被提出作为基于 is proposed as a representative work for CNN的生成模型构建的代表工作,该模型可实现语音识别,语音合成和音乐生成任务。-based generative model building, which enables speech recognition, speech synthesis, and music generation tasks. WaveNet架构呈现了许多因果卷积层,有点类似于递归层。然而,它有两个局限性:其低效的计算减少了实时的使用,并且它被创建为主要面向声学数据。用于符号数据的迷笛网 architecture presents a number of causal convolutional layers, somewhat similar to recurrent layers. However, it has two limitations: its inefficient computation reduces the use of real time, and it was created to be mainly oriented to acoustic data. MidiNet [22] 架构的灵感来自波浪网。它包括一个调整机制,该机制结合了先前测量的历史信息(旋律和和弦)。作者讨论了控制创造力和限制条件的两种方法。一种方法是仅在生成器架构的中间卷积层中插入调整数据。另一种方法是减小特征匹配正则化的两个控制参数的值,从而减少实际数据和生成数据的分布。architecture for symbolic data is inspired by WaveNet. It includes an adjustment mechanism that incorporates historical information (melody and chords) from previous measurements. The authors discuss two ways to control creativity and constrain the condition. One method is to insert adjustment data only in the middle convolutional layers of the generator architecture. The other method is to reduce the value of two control parameters of feature-matching regularization, thus reducing the distribution of actual and generated data.

-

基于复合架构的音乐生成。Compound architecture-based music generation. Bretan等人 et al. [32]通过开发深度自动编码器实现了音乐输入的编码,并通过从库中进行选择来重建输入。随后,他们建立了一个深度结构化的语义模型 implemented the encoding of musical input by developing a deep autoencoder and reconstructed the input by selecting from a library. Subsequently, they established a deep-structured semantic model DSSM与LSTM相结合,对单音旋律进行单音预测。但是,由于统一预测的局限性,生成的内容的质量有时很差。 combined with LSTM to perform unitary prediction of monophonic melody. However, because of the limitations of unitary prediction, the quality of the generated content is sometimes poor. Bickerman等人 et al. [24]提出了一种使用深度信仰网络学习爵士乐的音乐编码方案。该模型可以生成不同音调的灵活和弦。它表明,如果爵士乐语料库足够大以产生和弦,那么有理由相信可以演奏更复杂的爵士乐语料库。虽然已经创建了一些有趣的爵士旋律片段,但模型生成的短语不足以代表爵士乐语料库的所有特征。 proposed a music-coding scheme for learning jazz using deep belief networks. The model can generate flexible chords of different tones. It demonstrates that if the jazz corpus is large enough to generate chords, there is reason to believe that more complex jazz corpora can be performed. While some interesting pieces of jazz melodies have been created, the phrases generated by the model are not sufficient to represent all the features of the jazz corpus. Lyu等人 et al. [11]结合了 combined the capability of LSTM在长期数据训练中的能力和受限玻尔兹曼机(RBM)在高维数据建模中的优势。结果表明,该模型在和弦音乐的生成中具有良好的泛化效果,但一些高质量的音乐片段很少见。Chu等人 in long-term data training and the advantages of the Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM) in high-dimensional data modeling. The results demonstrate that the model has a good generalization effect in the generation of chord music, but some high-quality music clips are rare. Chu et al. [12]提出了一种基于音符元素生成流行音乐的分层神经网络模型。下层处理旋律生成,上层产生和弦和鼓。该模型的两个实际应用与认知水平的神经舞蹈和神经叙事有关。然而,这种模式的缺点还在于基于音符的生成模式,其中不包括音乐理论研究,从而限制了其音乐创造力和风格完整性。 proposed a hierarchical neural network model for generating pop music based on note elements. The lower layer handles melody generation, and the upper layer produces chords and drums. Two practical applications of this model are related to neural dance and neural storytelling at the cognitive level. However, the shortcoming of this model also lies in the note-based generation mode, which does not include music theory research, thus limiting its musical creativity and stylistic integrity. Lattner等人 et al. [25]通过设计一种 learn the local structure of music by designing a C-RBM架构来学习音乐的局部结构,该架构仅在时间维度上利用卷积来模拟时间不变性,而不是音高不变性,从而打破了音高的概念。其核心思想是在语法上简化音乐生成之前的音乐生成结构,例如音乐模式,节奏模式等。缺点是音乐结构被抄袭。黄等人 architecture that utilizes convolutions only in the temporal dimension in order to model time invariance, instead of pitch invariance, breaking the concept of pitch. Its core idea is to grammatically reduce the structure of music generation before music generation, such as music mode, rhythm pattern, etc. The disadvantage is that the musical structure is plagiarized. Huang et al. [26]提出了一种基于变压器的音乐生成模型。该算法的核心是将中间内存要求减少到线性序列的长度。最后,可以在几分钟内生成一个很小的片段步骤的组合,并在 proposed a transformer-based model for music generation. The core of the algorithm is to reduce the intermediate memory requirement to the length of the linear sequence. Finally, it’s possible to generate a combination of tiny segment steps for a few minutes and use it in JBS合唱团中使用它。尽管对 Choir. Despite the experimental comparison of Maestro的两个经典公共音乐数据集进行了实验性比较,但定性评估相对粗略。o’s two classic public music datasets, the qualitative evaluation was relatively crude.

-

Nesting—Nesting one model into another structure to form a new model. Examples include stacked autoencoder architectures [29] and RNN encoder-decoder architectures, where two RNN models are nested in the encoder and decoder parts of an autoencoder, so we can also call them autoencoders (RNN, RNN) [16].

-

Instantiation—The architectural pattern is instantiated into a given architecture. For a case in point, the Anticipation-RNN architecture instantiates a conditional reflection architectural pattern onto an RNN and the output of another RNN as a conditional reflection input, which we can call conditional reflection (RNN, RNN) [17]. The C-RBM architecture is a convolutional architectural pattern instantiated onto an RBM architecture, which we can note as convolutional (RBM) [30].

2. Deep Learning-Based Music Generation

-

基于 RNN 的音乐生成

3. 中国传统音乐计算Traditional Chinese Music Computing

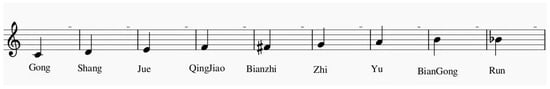

据我们所知,很少有可用的基于To our knowledge, there are few available MIDI的中国民间音乐数据集。Luo等人-based datasets of Chinese folk music. Luo et al. [33]提出了一种基于自动编码器生成特定流派的中国民歌的算法。然而,结果只能产生更简单的片段,并没有从音乐类型的角度对音乐进行定性分析。李等人 proposed an algorithm to generate genre-specific Chinese folk songs based on auto-encoder. However, the results could only produce simpler fragments and did not perform qualitive analysis of the music from a musical genre perspective. Li et al. [34]提出了一种基于条件随机场( presented a combined approach based on Conditional Random Field (CRF)和RBM的中国民歌分类组合方法。值得注意的是,这种方法是从音乐理论角度对分类结果进行深入的定性分析。Zheng等人) and RBM for classifying traditional Chinese folk songs. Such an approach is noteworthy for being the first in-depth qualitative analysis of the classification results from a music-theoretical perspective. Zheng et al. [35]重构了速度更新公式,提出了一种基于空间粒子群算法的中国民乐创作模型。黄 reconstructed the speed-update formula and proposed a Chinese folk music creation model based on the spatial particle swarm algorithm. Huang [36]从基于中国旋律的两个音乐元素中收集数据,分析了中国旋律意象在创作中国民乐中的应用价值。张等 collected data from two musical elements based on Chinese melody, and analyzed the application value of Chinese melody imagery in creating traditional Chinese folk music. Zhang et al. [37,,38]对中国传统五音群进行了音乐数据文本化和聚类分析。综上所述,我们的动机是制作具有层次结构的中国五音音乐和具有多种音乐特征和统一节奏的局部五音音乐,如图 conducted music data textualization and cluster analysis on Chinese traditional pentatonic groups. In summary, our motivation is to produce Chinese pentatonic music with hierarchical structure and local pentatonic music with multiple musical features and uniform rhythms, as shown in Figure 1 [39]所示。.

图Figure 1.中国传统五音阶中的五个主要音阶和四个部分音阶。 The five main scales and four partial scales in traditional Chinese pentatonic music.

References

- Cope, D. The Algorithmic Composer; AR Editions, Inc.: Middleton, WI, USA, 2000; Volume 16.

- Nierhaus, G. Algorithmic Composition: Paradigms of Automated Music Generation; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009.

- Herremans, D.; Chuan, C.H.; Chew, E. A functional taxonomy of music generation systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2017, 50, 1–30.

- Fernández, J.D.; Vico, F. AI methods in algorithmic composition: A comprehensive survey. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2013, 48, 513–582.

- Briot, J.P.; Pachet, F. Deep learning for music generation: Challenges and directions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 981–993.

- Liu, C.H.; Ting, C.K. Computational intelligence in music composition: A survey. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2016, 1, 2–15.

- Fiebrink, R.; Caramiaux, B. The machine learning algorithm as creative musical tool. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.00379.

- Acampora, G.; Cadenas, J.M.; De Prisco, R.; Loia, V.; Munoz, E.; Zaccagnino, R. A hybrid computational intelligence approach for automatic music composition. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE 2011), Taipei, Taiwan, 27–30 June 2011; pp. 202–209.

- Kong, Q.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Giantmidi-piano: A large-scale midi dataset for classical piano music. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.07061.

- Aiolli, F. A Preliminary Study on a Recommender System for the Million Songs Dataset Challenge. In Proceedings of the ECAI Workshop on Preference Learning: Problems and Application in AI, State College, PA, USA, 25–31 July 2013; pp. 73–83.

- Lyu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Meng, H. Modelling high-dimensional sequences with lstm-rtrbm: Application to polyphonic music generation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015.

- Chu, H.; Urtasun, R.; Fidler, S. Song from PI: A musically plausible network for pop music generation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.03477.

- Choi, K.; Fazekas, G.; Sandler, M. Text-based LSTM networks for automatic music composition. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1604.05358.

- Johnson, D.D. Generating polyphonic music using tied parallel networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Evolutionary and Biologically Inspired Music and Art, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 2017; pp. 128–143.

- Lim, H.; Rhyu, S.; Lee, K. Chord generation from symbolic melody using BLSTM networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.01011.

- Sun, F. DeepHear—Composing and Harmonizing Music with Neural Networks. 2017. Available online: https://fephsun.github.io/2015/09/01/neural-music.html (accessed on 1 September 2015).

- Hadjeres, G.; Nielsen, F. Interactive music generation with positional constraints using anticipation-RNNs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1709.06404.

- Waite, E.; Eck, D.; Roberts, A.; Abolafia, D. Project Magenta: Generating Long-Term Structure in Songs and Stories. Available online: https://magenta.tensorflow.org/2016/07/15/lookback-rnn-attention-rnn (accessed on 15 July 2016).

- Mehri, S.; Kumar, K.; Gulrajani, I.; Kumar, R.; Jain, S.; Sotelo, J.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. SampleRNN: An unconditional end-to-end neural audio generation model. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.07837.

- Myburgh, J.C.; Mouton, C.; Davel, M.H. Tracking translation invariance in CNNs. In Proceedings of the Southern African Conference for Artificial Intelligence Research, Muldersdrift, South Africa, 22–26 February 2021; pp. 282–295.

- Oord, A.v.d.; Dieleman, S.; Zen, H.; Simonyan, K.; Vinyals, O.; Graves, A.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Senior, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Wavenet: A generative model for raw audio. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.03499.

- Yang, L.C.; Chou, S.Y.; Yang, Y.H. MidiNet: A convolutional generative adversarial network for symbolic-domain music generation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.10847.

- Dong, H.W.; Hsiao, W.Y.; Yang, L.C.; Yang, Y.H. Musegan: Multi-track sequential generative adversarial networks for symbolic music generation and accompaniment. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32.

- Bickerman, G.; Bosley, S.; Swire, P.; Keller, R.M. Learning to Create Jazz Melodies Using Deep Belief Nets. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Computational Creativity, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–9 January 2010.

- Lattner, S.; Grachten, M.; Widmer, G. Imposing higher-level structure in polyphonic music generation using convolutional restricted boltzmann machines and constraints. J. Creat. Music. Syst. 2018, 2, 1–31.

- Huang, C.Z.A.; Vaswani, A.; Uszkoreit, J.; Shazeer, N.; Hawthorne, C.; Dai, A.; Hoffman, M.; Eck, D. Music transformer: Generating music with long-term structure. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.04281.

- Roberts, A.; Engel, J.; Raffel, C.; Hawthorne, C.; Eck, D. A hierarchical latent vector model for learning long-term structure in music. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4364–4373.

- Roberts, A.; Engel, J.; Raffel, C.; Simon, I.; Hawthorne, C. MusicVAE: Creating a Palette for Musical Scores with Machine Learning. 2018. Available online: https://magenta.tensorflow.org/music-vae (accessed on 15 March 2010).

- Chung, Y.A.; Wu, C.C.; Shen, C.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, L.S. Audio word2vec: Unsupervised learning of audio segment representations using sequence-to-sequence autoencoder. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.00982.

- Boulanger-Lewandowski, N.; Bengio, Y.; Vincent, P. Modeling temporal dependencies in high-dimensional sequences: Application to polyphonic music generation and transcription. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1206.6392.

- Hadjeres, G.; Pachet, F.; Nielsen, F. Deepbach: A steerable model for bach chorales generation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1362–1371.

- Bretan, M.; Weinberg, G.; Heck, L. A unit selection methodology for music generation using deep neural networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.03789.

- Luo, J.; Yang, X.; Ji, S.; Li, J. MG-VAE: Deep Chinese folk songs generation with specific regional styles. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Sound and Music Technology (CSMT); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 93–106.

- Li, J.; Luo, J.; Ding, J.; Zhao, X.; Yang, X. Regional classification of Chinese folk songs based on CRF model. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 11563–11584.

- Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Shen, L.; Gao, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y. Algorithm composition of Chinese folk music based on swarm intelligence. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2017, 8, 437–446.

- Kuo-Huang, H. Folk songs of the Han Chinese: Characteristics and classifications. Asian Music 1989, 20, 107–128.

- Liumei, Z.; Fanzhi, J.; Jiao, L.; Gang, M.; Tianshi, L. K-means clustering analysis of Chinese traditional folk music based on midi music textualization. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 9–11 April 2021; pp. 1062–1066.

- Zhang, L.M.; Jiang, F.Z. Visualizing Symbolic Music via Textualization: An Empirical Study on Chinese Traditional Folk Music. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile Multimedia Communications, Guiyang, China, 23–25 July 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 647–662.

- Xiaofeng, C. The Law of Five Degrees and pentatonic scale. Today’s Sci. Court. 2006, 5.

More