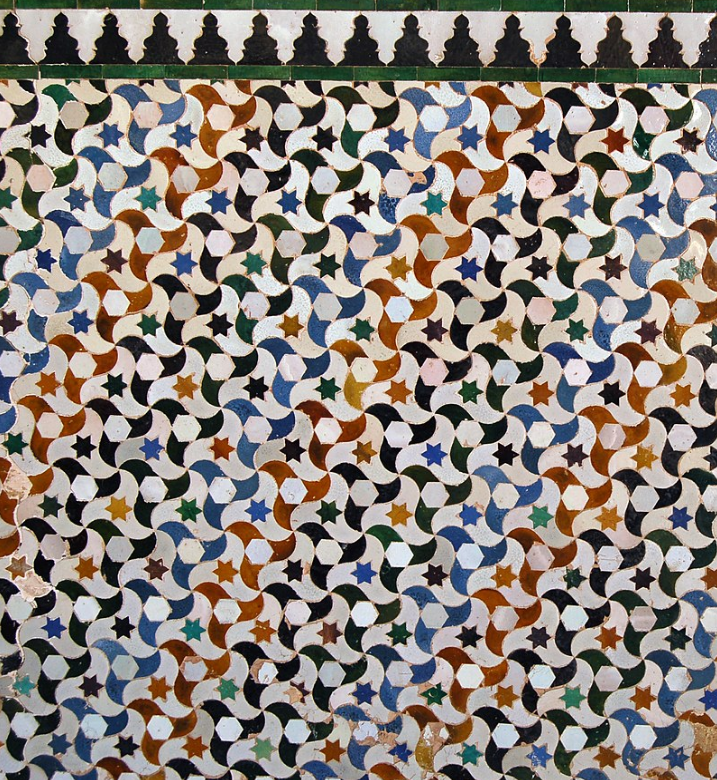

Zellige (Arabic: [zˈliʑ]; Arabic: الزليج; also zelige or zellij) is mosaic tilework made from individually chiseled geometric tiles set into a plaster base. This form of Islamic art is one of the main characteristics of Moroccan architecture. It consists of geometrically patterned mosaics, used to ornament walls, ceilings, fountains, floors, pools and tables.

- الزليج

- zelige

- zellige

1. History

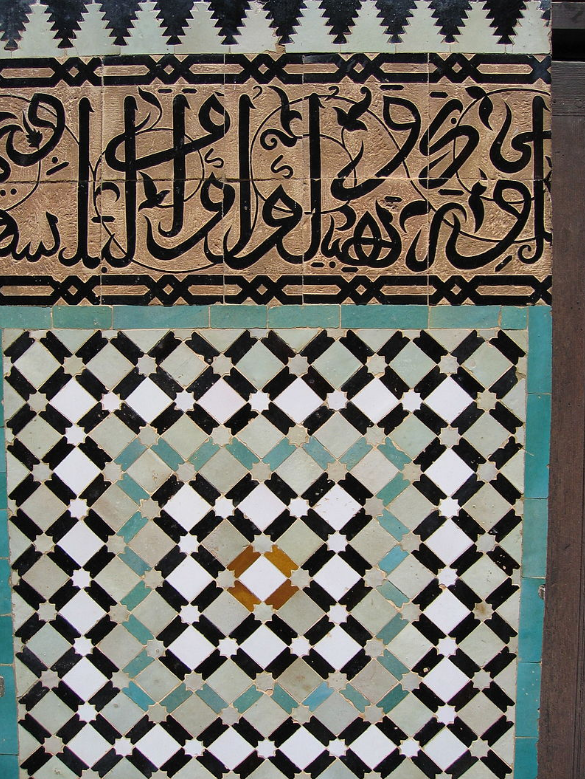

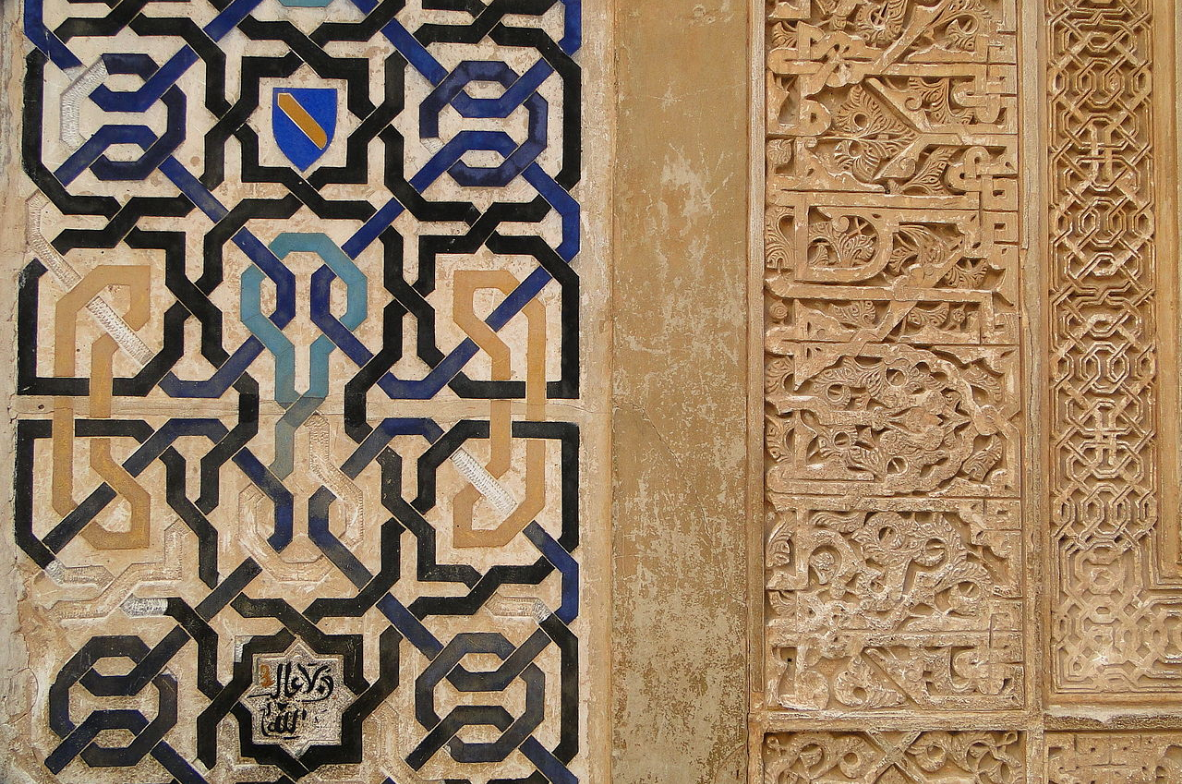

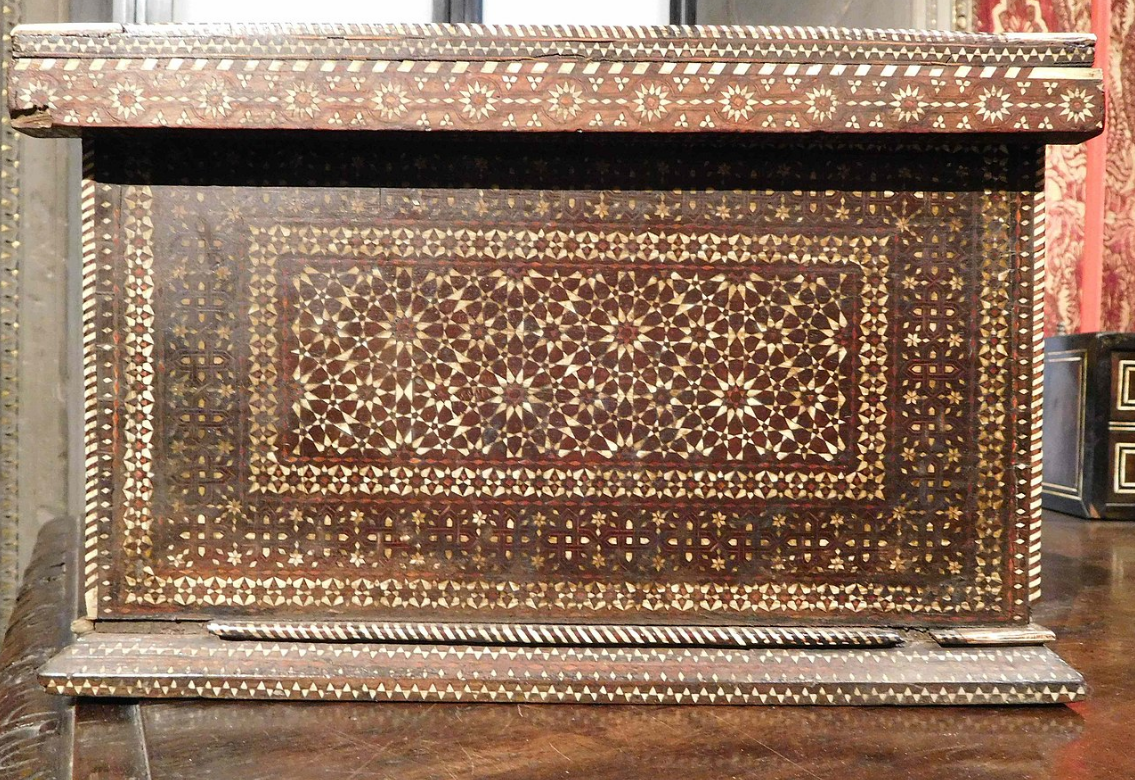

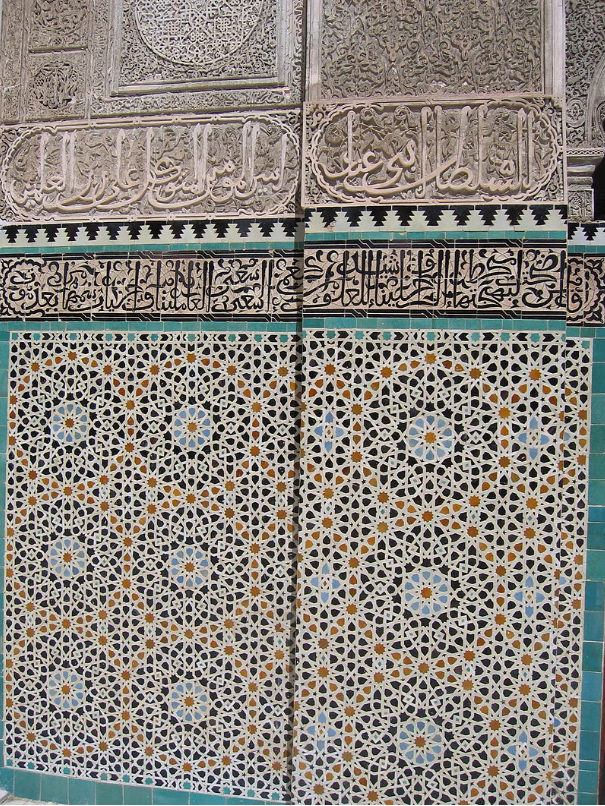

The Moorish art of zellige flourished during the Hispano-Moresque period (Azulejo) of the Maghreb and the area known as Al-Andalus (modern day Spain ) between 711-1492. The technique was highly developed during the Nasrid dynasty and Merinid dynasty who gave it more importance around the 14th century and introduced blue, green and yellow colours. Red was added in the 17th century. The old enamels with the natural colours were used until the beginning of the 20th century and the colours had probably not evolved much since the period of Merinids. The cities of Fes and Meknes in Morocco, remain the centers of this art.

Patrons of the art used zellige historically to decorate their homes as a statement of luxury and the sophistication of the inhabitants. Zellige is typically a series of patterns utilizing colourful geometric patterns. This framework of expression arose from the need of Islamic artists to create spatial decorations that avoided depictions of living things, consistent with the teachings of Islamic law.

2. Clays for Zellige

Fez and Meknes in Morocco are still the production centers for zellige tiles due to the Miocene grey clay of Fez. The clay from this region is primarily composed of Kaolinite. For Fez and Meknes, the clay composition is 2-56% clay minerals, calcite 3-29%. Meriam El Ouahabi states that:

From the other sites (Meknes, Fes, Salé and Safi), the clay mineral composition shows besides kaolinite the presence of illite, chlorite, smectite and traces of mixed layer illite/chlorite (Fig. 3). Meknes clays belong to illitic clays, characterized by illite (54 – 61%), kaolinite (11 – 43%), smectite (8 – 12%) and chlorite (6 – 19%) (Fig. 3). Fes clays have a homogeneous composition (Fig. 3) with illite (40 – 48%). and kaolinite (18 – 28%) as the most abundant clay minerals. Chlorite (12 – 15%) and smectite (9 – 12%) are generally present as small quantities. Mixed layer illite/chlorite is present in trace amounts in all the examined Fes clay materials.[1]

3. Forms and Trends

As the colour palette of the zellige tiles increased over the centuries, it became possible to multiply the compositions ad infinitum. The most current form of the zellige is a square. Other forms are possible: the octagon combined with a cabochon, a star, a cross, etc. It is then moulded with a thickness of approximately 2 centimetres. There are simple squares of 10 by 10 centimeters or with the corners cut to be combined with a coloured cabochon. To pave an area, bejmat, a paving stone of 15 by 5 centimetres approximately and 2 centimetres thick, can also be used.

"An encyclopedia could not contain the full array of complex, often individually varied patterns and the individually shaped, hand-cut tesserae, or furmah, found in zillij work. Star-based patterns are identified by their number of points—'itnashari for 12, 'ishrini for 20, arba' wa 'ishrini for 24 and so on, but they are not necessarily named with exactitude. The so-called khamsini, for 50 points, and mi'ini, for 100, actually consist of 48 and 96 points respectively, because geometry requires that the number of points of any star in this sequence be divisible by six. (There are also sequences based on five and on eight.) Within a single star pattern, variations abound—by the mix of colors, the size of the furmah, and the complexity and size of interspacing elements such as strapping, braids, or "lanterns." And then there are all the non-star patterns— honeycombs, webs, steps and shoulders, and checkerboards. The Alhambra's interlocking zillij patterns were reportedly a source of inspiration for the tessellations of modern Dutch artist M.C. Escher."[2]

Themes often employ Kufic script, as it fits well with the geometry of the mosaic tiles, and patterns often culminate centrally in the Rub El Hizb. The tessellations in the mosaics are currently of interest in academic research in the mathematics of art.

-

Medersa Bou Inania, Fes

-

Bab Mansour, Meknes

-

Place El-Hedine, Meknes

-

Saadian Tombs. By Yastay - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=46083914

-

Classic motif and colors of the 14th century in the Alhambra. By gema de la fuente - La Alhambra, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21857441

-

Merinid Zellige from the Chellah in Rabat, Morocco. By Jc wik m001 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=54830020

These studies require expertise not only in the fields of mathematics, art and art history, but also of computer science, computer modelling and software engineering,[3] all used for the Hassan II Mosque.

Islamic decoration and craftsmanship had a significant influence on Western art when Venetian merchants brought goods of many types back to Italy from the 14th century onwards.[4]

4. Zellige Craftsmanship

Zellige making is considered an art in itself. The art is transmitted from generation to generation by maâlems (master craftsmen). A long training starts at childhood to implant the required skills.[5]

Assiduous attention to detail is needed when creating zellige. The small shapes (cut according to a precise radius gauge), painted and enamel covered pieces are then assembled in a geometrical structure as in a puzzle to form the completed mosaic. The process has not varied for a millennium, though conception and design has started using new technologies such as data processing.

-

Artisan workers chipping zellige pieces, Fez, Morocco. By Dan Lundberg - https://www.flickr.com/photos/9508280@N07/24116015119, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49870587

References

- El Ouahabi, Meriam (2014). "Mineralogical and geotechnical characterization of clays from northern Morocco for their potential use in the ceramic industry". Clay Minerals 49: 35–51. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261479494_Preliminary_mineralogical_and_geotechnical_characterization_of_clays_from_Morocco_application_to_ceramic_industry.

- Werner, Louis. 2001. "Zillij in Fez." Saudi Aramco World. May–June 2001. Volume 52 (3). Pages 18–31. http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/200103/zillij.in.fez.htm

- From Form to Content: Using Shape Grammars for Image Visualization, Source IV archive Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Information Visualisation (IV'05) – Volume 00, IEEE Computer Society Washington, DC, USA

- Mack, Rosamond E. (2001). Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600. University of California Press. pp. Chapter 1. ISBN 0-520-22131-1.

- beton-decoratif.com http://www.beton-decoratif.com/infos.htm