You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Syed Fida Hassan and Version 3 by Lindsay Dong.

Magnesium has been found to have special osteoconductive properties, which is much appreciated when used as bone implants. It has been reported that Mg, as a cofactor of the alkaline phosphatase isozymes, helps in the healing and remodeling of the bone tissue [10]. Magnesium-based stents are also useful where biodegradable nasal stents could help avoid treatment failure that occurs due to the secondary operations that are required of traditional implants [11]. The potential application of biodegradable magnesium alloys is not limited to its use as temporary implants.

- magnesium

- implant

- biodegradable

- alloying element

1. Introduction

Biodegradable materials for implants have been in clinical use for some time now [1]. These materials have come into prominence in lieu of non-biodegradable, permanent implants, which have had temporary applications to afford the body a healing period after which the implants are no longer required. The use of permanent implants for temporary applications meant a secondary operation is carried out to remove the implant. Apart from the obvious trauma and the inconvenience suffered by the patients and their families, it also meant added medical costs and medical resources are spent in this ordeal, not to mention the economic value of time spent by all parties involved. These permanent implants were mostly either titanium or steel-based alloys. Common issues of the resulting ‘effects’ by the permanent orthopedic implants include inflammation, infection, stress shielding, and consequent bone loss. Stress shielding is due to the higher stiffness of the implants, leading to the dis-use of adjacent bones and further leading to a gradual loss of bone structure and weakening of the bones. The solution has been the use of biodegradable materials for implants, which would corrode naturally within the body, after or during affording the required time for the healing. Biodegradable materials such as biodegradable polymers (with polyglycolic acid (PGA) and polylactic acid (PLA) being most common), bioceramics (Tricalcium phosphate (TCP), Hydroxyapatite (HA)), and biodegradable Mg alloys [2] have been in increasing use for this reason. The applications included bone fixtures such as nails [3], screws [4], clips [5], wires [6], and stents [7].

2. Requirements for Bio Application of Mg Alloys and Their Corrosion Strengths

The biocompatibility of magnesium biodegradable alloy is determined via cytotoxicity tests conducted either in vitro or in vivo. The cytotoxicity tests are mainly designed to test for either the cell proliferation in a given medium of magnesium-degraded products or cell adhesion to the magnesium alloy being tested. The standard of the in vitro tests is usually performed as in standard ISO 10993 part 5 [8][9][10][11][24,25,26,27]. However, there has been poor correlation between in vitro and in vivo studies when using the ISO 10993 standard [8][11][24,27] due to which, in recent years, there have been studies to propose a modified approach to the standards of in vitro testing of cytotoxicity. Some researchers suggested dilution of the extracts to achieve more accurate in vitro tests. The release of gases to the surrounding vicinity, i.e., tissue [12][30] and bone, is investigated to determine its influence and effects. Slower degradation rates are necessary for low gas evolution rates. Higher rates of evolution of H2 gas could lead to inflammation and swelling of the surrounding tissue. Similarly, gas pockets and the pressure associated with the release of H2 could lead to deformations during the osteogenesis applications of magnesium alloys. Due to the above-mentioned limitations, only those elements with positive or negligibly negative effects to the human body should be considered for use as in applications involving biodegradable magnesium alloys. The requirements for bio application of the magnesium alloys are (i) uniform corrosion degradation, (ii) a slow and controlled degradation rate, and (iii) good cytotoxicity.3. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties Mg Alloys

3.1. Effect of the Alloying Elements

The microstructures of Mg-alloys are mainly composed of an α-Mg matrix with some amount of alloying element in them, followed by secondary phases. These secondary phases are primarily located in the grain boundaries. The mode of formation when casting is that the secondary phases accumulate in advance of the forming grains. The secondary phases appear as precipitates along the grain boundary [13][88]. However, in some cases, the secondary phases are also present in the dendritic structures, if present [14][110]. The microstructure of the Mg alloy is dependent on the alloying elements as well as the work history of the alloy. This can be seen from the results of Table 15.Table 15.

A summary of the mechanical properties of some of the Mg binary alloys as reported in various literature.

| Materials | YS, MPa | UTS, MPa | UCS, MPa | Elongation, % | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-Cast | As-Rolled | As-Extruded | As-Cast | As-Rolled | As-Extruded | As-Cast | As-Rolled | As-Extruded | As-Cast | As-Rolled | As-Extruded | Ref | |

| Mg | 20.83 | 113.2 | - | 86.69 | 169.6 | - | - | - | - | 13.06 | 12.26 | - | [15][62] |

| Mg-1Al | 42.34 | 168.8 | - | 159.94 | 230.1 | - | - | - | - | 16.58 | 6.09 | - | |

| Mg-1Ag | 23.86 | 126.9 | - | 116.26 | 196.6 | - | - | - | - | 13.34 | 6.687 | - | |

| Mg-1In | 35.62 | 133.5 | - | 145.82 | 191.6 | - | - | - | - | 14.96 | 9.473 | - | |

| Mg-1Mn | 28.9 | 116.5 | - | 82.99 | 172.1 | - | - | - | - | 7.536 | 3.741 | - | |

| Mg-1Si | 80.3 | 120.7 | - | 194.21 | 196.1 | - | - | - | - | 14.85 | 3.582 | - | |

| Mg-1Sn | 35.28 | 146 | - | 149.18 | 203.2 | - | - | - | - | 20.04 | 6.647 | - | |

| Mg-1Y | 25.54 | 146.8 | - | 74.59 | 199.9 | - | - | - | - | 9.992 | 9.154 | - | |

| Mg-1Zn | 25.54 | 160.5 | - | 133.39 | 239.7 | - | - | - | - | 18.25 | 7.124 | - | |

| Mg-1Zr | 67.2 | 131 | - | 172.03 | 182.9 | - | - | - | - | 27.02 | 17.27 | - | |

| Mg-1Ca | 40.26 | 123.7 | 136.2 | 71.54 | 166.8 | 240.13 | - | - | - | 1.911 | 3.196 | 10.81 | |

| Mg-0.57Cu | - | - | - | 104.14 | - | - | 167.48 | - | - | - | - | - | [16][65] |

36.1.1. Mg

Mg in its pure form exists in an α-Mg phase, which has hexagonal close pack (HCP) structures with dimensions of a = 0.32 nm and c = 10.3 nm [13][88]. The addition of further alloying elements render the different characteristics associated with the formation of their respective secondary and tertiary phases. These initially formed phases undergo additional changes during further processing of the Mg alloy. Therefore, it is necessary to look at some of the alloying elements and the commonly formed phases with Mg found in the literature. For this purpose, only the elements with sufficient biocompatibility have been chosen for further discussion. Pure Mg has an ultimate compressive strength (UCS) of approximately 185.67 MPa and an ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of approximately 63 MPa [16][65].36.1.2. Zn

Zinc forms the intermetallic phase MgZn, which is mainly present in the grain boundary [17][116]. It has a solubility limit of approximately 2.6 wt.% in Mg [18][117]. It has been reported by C.J. Boehlert and K. Knittel [19][118] that Zn of 4 wt.% produced the highest refinement of the grain size in the Mg binary alloy. Similarly, S. Cai et al. [17][116] indicated that the addition of Zn up to 5 wt.%. increased the mechanical properties of Mg alloys, which has been attributed to the grain refinement, solid solution strengthening, and second-phase strengthening. Based on this, optimal Zn content can be said to be between 4 and 5 wt.% for grain refinement. On the other hand, the elongation % was the highest when 1 wt.%. Zn was used [17][116]. Mg-Zn alloy produced from powder metallurgy produced fine, equiaxed grains and row elongated grains. Strike-like coarse intermetallic phases were also reportedly produced with increased Zn concentrations [20][119]. Zn addition to Mg-6 wt.%Sn was investigated by N. El Mahallawy et al. [21][120] with the addition of Zn wt.% of 2 and 4. In as-cast alloys, Zn acted as a grain refiner to the Sn, further complimenting the grain-refining characteristic of Sn itself. Zn addition increased the grain size of as-rolled and as-extruded alloys as well.36.1.3. Ca

Y. C. Lee et al. [22][121] reported that the addition of Ca up to 0.4 wt.% resulted in significant grain refinement of approximately 270 μm, and any additional grain refinement was reported to have only minor changes in grain size. Research conducted by Z. Li et al. [23][64] on Mg-Ca binary alloys with 1–3 wt.% of Ca found that the yield strength (YS), UTS, and elongation of the binary Mg alloy decreased with increasing Ca content for the as-cast alloys. The UTS and elongation were successively increased after hot rolling and hot extrusion [23][64]. The loss in mechanical properties has been attributed to the embrittlement of the alloy owing to the secondary phase Mg2Ca. An increase in this Mg2Ca was found to enhance the corrosion rate of the alloy. The formation of the Mg2Ca phase, in proximity to Fe and Si, have been reported to lead to pitting corrosion [24][96].36.1.4. Cu

Recent works by C. Liu et al. [16][65] produced Mg-Cu alloys of approximate grain size 100 μm. Mg2Cu secondary-phase precipitates form with an increasing Cu content (0.05, 0.1, 0.5 wt.%.) and have been reported to be present as a discontinuous distribution along the grain boundaries as well as in the grains as particles [16][65]. A similar study by Y. Li et al. [25][123] in their supplementary data reported obtaining a Mg-Cu alloy grain size of approximately 300 μm, and with an increasing Cu content (0.05, 0.1, 0.25 wt.%.), the presence of secondary-phase Mg2Cu becomes more visible in the form of a globular presence, mainly at the grain boundaries and a small amount inside the grains.36.1.5. Si

Si is also a grain refiner of Mg [22][121]. Si has been reported to have produced approximately 240 μm. Si forms the secondary phase of Mg2Si, which, after annealing, becomes finer and more homogenized [26][122]. If the Si concentration becomes more than the eutectic concentration limits, that secondary phase crystallizes in the form of needles, resulting in increased brittleness [27][125]. Si, when added to Mg alloys containing Ca, forms CaMgSi [26][122].36.1.6. Mn

The maximum solubility of manganese in magnesium is only approximately 2.2 wt.% [28][126]. It has been reported by Gu et al. [15][62] that the addition of Mn below this volume results in complete solubility of Mn in Mg and only a purely α-Mg matrix is formed. Moreover, they also noted that the addition of Mn does not contribute to an enhancement of strength, but rather lowers the elongation.36.1.7. Sn

Tin has a solid solubility limit of 14.5 wt.% in Mg [29][127] and forms the secondary-phase of Mg2Sn in binary alloys [30][31][32][63,67,128], which may not be detected by XRD in low volumes (<3 wt.%) [31][67]. This eutectic phase is found as particles between the α-Mg dendrites [30][63]. C. Zhao et al. [31][67] reported that with 1 wt.% Sn, a near equiaxed grain structure was formed while Sn content of 3 wt.% and higher gave rise to dendrites of α-Mg where the secondary dendrite arm spacing of the alloys decreased with increasing Sn content. Binary alloys of Mg-Sn are composed of an α-Mg matrix, a eutectic composition of α-Mg + Mg2Sn, and Mg2Sn in a devoiced manner, as well as a distribution of tiny white particles [32][128]. For 5 wt.% Sn, UTS of over 130 MPa (40.7% increase), and an elongation of approximately 120 MPa (39.3% increase) compared with pure Mg, has been reported by H. Liu et al. [32][128]. Further increase in Sn content reduces both the UTS and ductility.36.1.8. Al

Al has a maximum solid solubility of 13 wt.% in Mg at eutectic temperatures [33][129]. Though the eutectic phase should theoretically appear at approximately 13 wt.% Al, it is present in as low as 2 wt.% Al during non-equilibrium cooling processes such as casting [33][129]. A β-Mg17Al12 phase forms in the grain boundaries and inter-dendritic regions of the alloy, with the dendrites being α-Mg. Additionally, the eutectic α-Mg with high concentrations of Al is also expected to be found in grain boundaries [33][129]. It has been reported that the addition of Al increases the porosity of the Mg alloy, until approximately 11% wt of Al is reached, after which the porosity decreases [conference paper]. The increase in Al content also correlated with an increase in the pore size of the alloy. Additionally of note is the undesirable interaction between zirconium and aluminum, which seems to limit the use of Zr along with Al in Mg alloys [33][129].36.1.9. Sr

Sr is known as a grain refiner of Magnesium alloys whereby it has been reported that an increase in its wt.% of 0.5–2% decreased the average grain size of binary Mg-Sr alloys [14][110]. Sr has a maximum solid solubility of 0.11 wt.% at a eutectic temperature [14][110] and its secondary phase with Mg is present as Mg17Sr2 [26][122] but is mostly concentrated in the grain boundaries [14][110]. These Mg17Sr2 have been reportedly been present in binary alloys of Mg-Sr (with wt.% 1–4) in a hexagonal structure where the base sides measure 10.469 nm with a c value of 10.3 nm [13][88]. For binary alloys of Mg-Sr, an increase in Sr wt.% of up to 2% has been found to increase the TYS and UTS [13][88]. H. Liu et al. [34][130] reported that the addition of Sr to the as-cast alloy Mg-5 wt.%Sn refined the microstructure and produced rod-shaped and bone-shaped secondary-phase MgSnSr, and the optimum mechanical properties were achieved with 2.14 wt.% Sr content. Additional Sr content resulted in decreased UTS and elongation, although TYS increased.36.1.10. Zr

This is normally added as a grain refiner, though its use in Mg alloys containing Al is not advised due to undesirable interactions between Zr and Al [33][129].36.1.11. Bi

Bismuth is known to be a grain refiner of Mg alloys [35][36][37][113,114,131]. Increasing Bi increased the grain refinement. For Bi up to 3 wt.%, a Mg3Bi2 phase was formed, and when used alongside Ca, Mg2Ca was formed, while between 5 and 12 wt.%, a Mg2Bi2Ca phase was present along with the Mg3Bi2 [36][114]. Greater than 0.5 wt.% of Bi has been attributed to a greater role of galvanic corrosion between the primary α-Mg and the secondary phases [36][114].36.1.12. Sc

0.2 wt.% Scandium added to ZK21 [38][115] has been reported to result in the grain refinement of ZK21.The alloy was as-cast and the resultant XRD analysis showed a single primary phase similar to the pure Mg pattern, indicating an α-Mg matrix with dissolved alloying elements.3.2. Effect of Processing

6.2. Effect of Processing

36.2.1. Liquid Metallurgy

Liquid metallurgy has the major advantage of producing bulk alloys and producing the starting material for various alloys. It is a principal process through which Mg alloy billets are produced for further processing. It has the chief advantage of being economically scalable for the large-scale industrial output of Mg alloys. All the alloys mentioned in this epaper, except that which has been produced by Powder Metallurgy (PM) or the newly emerging field of Additive Manufacturing (AM), have been produced by any one of the various casting processes.36.2.2. Powder Metallurgy

In recent years, a number of researchers [39][40][41][42][43][44][45][133,134,135,136,137,138,139] that produced Mg alloys used the Powder Metallurgy process route. This process is usually followed by extrusion to form the final alloy. PM has the advantage of uniform dispersal of the elements, and thereby uniformity of the secondary phases and a greater dissolution of the alloy elements in the αMg matrix.36.2.3. Extrusion and Rolling

Secondary mechanical processing are commonly used in Mg alloys to improve mechanical properties by modification of microstructure. In the study conducted by N. El Mahallawy et al. [21][120] on Mg-6Sn-xZn alloys (x: 0, 2, 4 wt.%), it was determined that grain sizes were vastly refined after extrusion and after rolling when compared with as-cast alloys [21][120], with the as-rolled alloys having the most refinement. Furthermore, the results of mechanical testing determined that the highest YS and UTS were produced for extruded alloys, followed by rolled alloys, with each of the processes producing superior strength for all values of Zn [21][120].36.2.4. Equal Channel Angular Pressing/Extrusion (ECAP/ECAE)

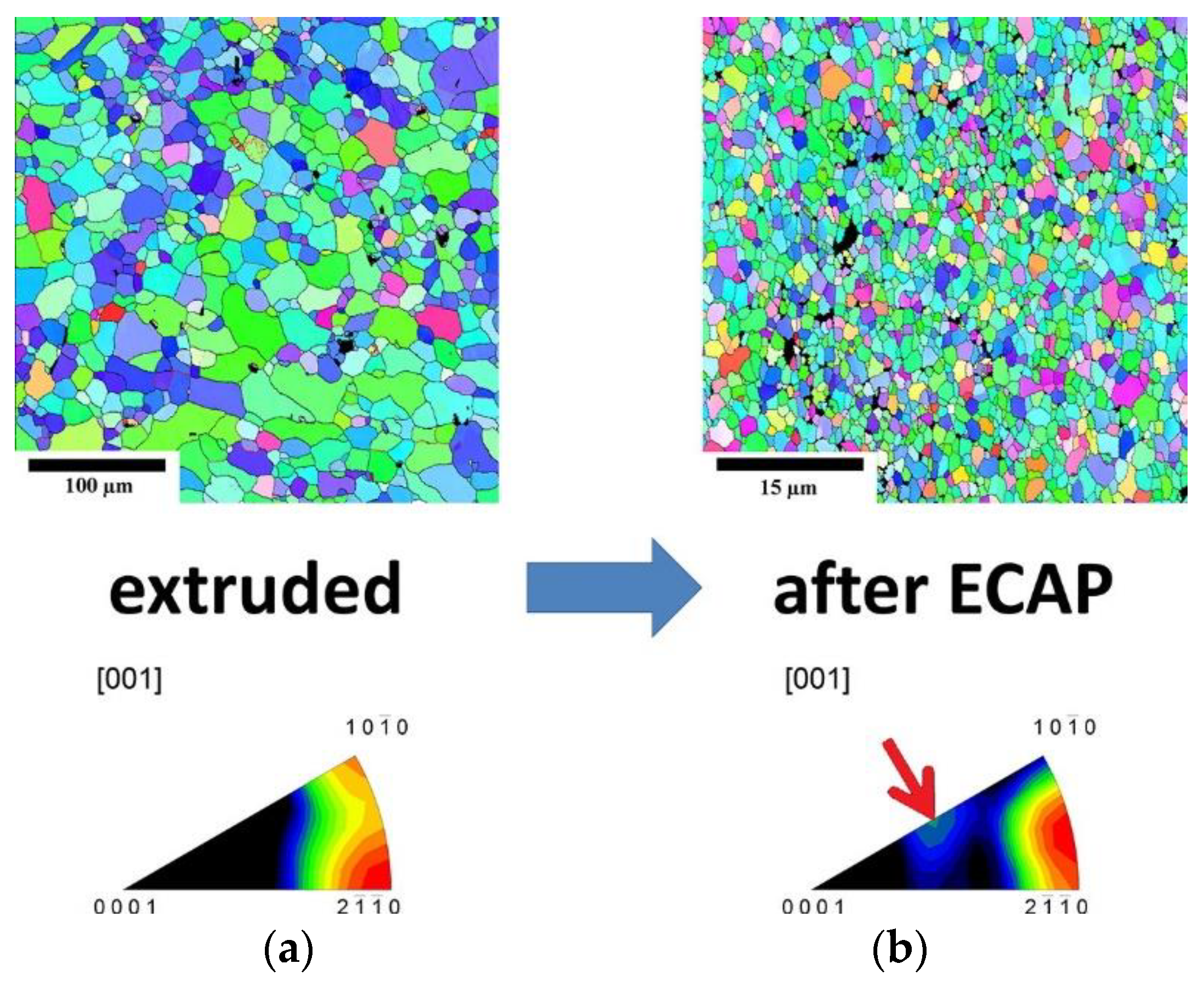

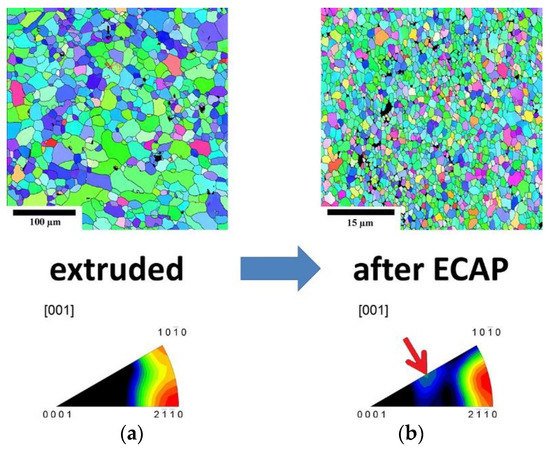

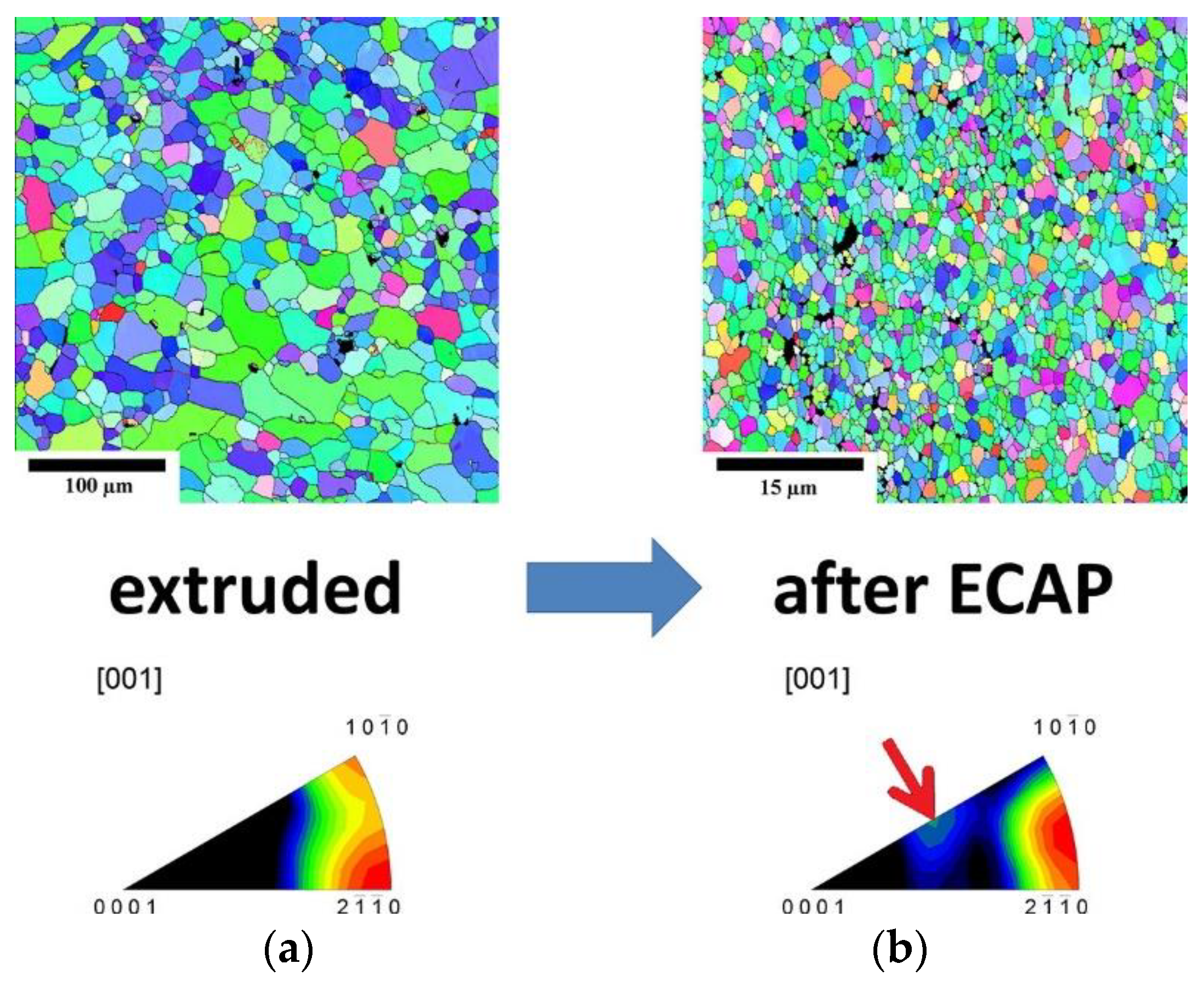

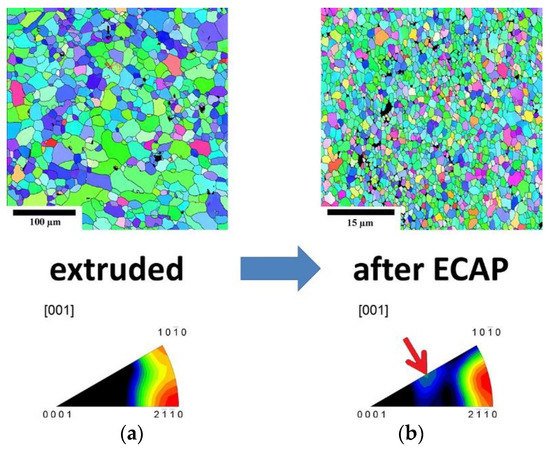

ECAP or ECAE [46][145], on the other hand, has the added advantage of producing grain refinement as well as equiaxed grains in comparison with extrusion via the change in direction of plastic deformation of the alloy. Through work carried out on LAE442 by P. Minárik et al. [47][146], it was found that the grain size of ~1 mm obtained by casting was refined down to ~1.7 μm after hot extrusion (350 °C) at a ratio of 22:1 followed by 12 passes of ECAP at 90° (See Figure 17).

3.3. Effect of Post-Processing Treatment

6.3. Effect of Post-Processing Treatment

It has been reported that the age-hardening response increases with increasing Sr content [14][110]. Homogenization of as-cast Mg-xSr (x: 0.5, 1, 2 wt.%) at 450 °C for 12 h followed by quenching in water dissolved the dendritic structures of the as-cast Mg-Sr alloy but it had no effect on the grain size [14][110]. Aging at 160 °C for 30 to 300 h showed that there was a reduction in hardness though it increased the UTS, TYS, and CYS [14][110]. H. Ibrahim et al. [48][149] performed solution treatment (510 °C, 3 h) age hardening in an oil bath (200 °C; 1 to 10 h) of a cast Mg alloy (Mg-1.2 wt.% Zn-0.5 wt.% Ca) and found that the heat treatment improved both the mechanical and degradation properties of the alloy.The development of Mg alloys is many times complemented by the development of various surface modification characteristics of the alloys/implants. The research in these areas concern the alteration of the implant surface characteristics in order to affect the corrosion characteristics as well as improve the initial cell adhesion and proliferation characteristics. These surface alterations are mainly of either the application of a coating on the alloy/composite surface or modification of the implant surface properties by various means. Both these methods impart different physical characteristics of the surface. A solution to develop biodegradable Mg alloy implants according to the different physical environments required by the various applications and locations could lie in tailoring application-specific surface modifications on high-performance Mg alloys.

One of the most common coating materials have been Hydroxyapatite (HA) [49][153]. The use of Micro Arc Oxidation techniques (MAO) for surface coating are also commonly found in the literature [49][50][51][52][153,154,155,156]. Tang et al. used this method to coat AZ31 with HA (Hydroxyapatite) and reported that it has induced additional resistance of the alloy to corrosion in Simulated Body Fluid by the barrier effect and the degradation of the coating itself. HA coating has also been said to result in enhanced osteoblast development compared to uncoated Mg alloy samples along with a significant reduction in the rate of degradation [53][157]. Furthermore, N. Yu et al. [54][158] reported that doping Strontium into the HA coatings to produce a dual layer of SrHA by microwave irradiationled to increased corrosion resistance of the initial stages of the Mg alloy. They also worked on commercially available AZ31 alloy.

V. K. Caralapatti and S. Narayanswamy [55][171] used High-Repetition Laser Shock Peening (HRLSP) to impart compressive residual stress on the surface of the Mg alloys to improve its degradation and biocompatibility. W. Jin et al. [56][172] carried out Nd ion implantation on WE43 using metal ion implanter with a Nd cathodic arc source. The retardation of the degradation rate and improvement in biocompatibility was attributed to a hydrophobic surface layer of mostly Nd2O3 and MgO.