Grongar Hill is located in the Welsh county of Carmarthenshire and was the subject of a loco-descriptive poem by John Dyer. Published in two versions in 1726, during the Augustan period, its celebration of the individual experience of the landscape makes it a precursor of Romanticism. As a prospect poem, it has been the subject of continuing debate over how far it meets artistic canons.

- romanticism

- carmarthenshire

- landscape

1. The Location

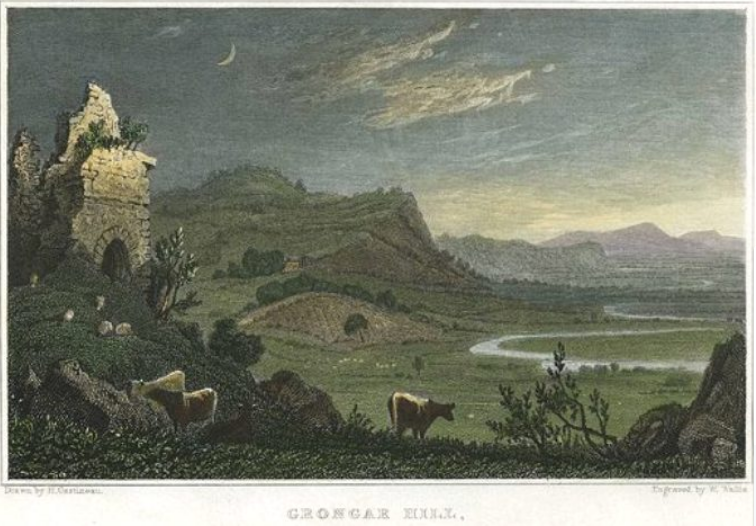

The hill lies in the parish of Llangathen and rises abruptly not far from the River Tywi. The Ordnance Survey reference is SN573215 / Sheet: 159 and the co-ordinates are latitude 51° 52' 23.85" N and longitude 4° 4' 23.17" W.[1] Its name derives from the Iron Age hillfort on its summit, in Welsh gron gaer (circular fort). At the hill's foot is the restored mansion of Aberglasney that once belonged to John Dyer’s family and where he grew up from 1710. The area was important during the Mediaeval period of Welsh independence[2] and from the 150 metre summit of the hill the ruins of several neighbouring castles can be seen; most notably “the luxurious groves of Dinevor, with its ruinated towers, present themselves with venerable majesty on the left; while the valley spreads in front….and the ruins of Dryslwyn castle, upon an insulated eminence in the middle of the vale.”[3]

2. The Poem

The first version of John Dyer’s poem appeared with a selection of others by him among the Miscellaneous Poems and Translations by Several Hands, published by Richard Savage in 1726. It was written in irregularly lined pindarics but the freshness of its approach was concealed beneath the heavily conventional poetic diction there. In the second section one finds “mossy Cells”, “shado’wy Side” and “grassy Bed” all within six lines of each other; and in the fourth appear “watry Face”, “show’ry Radiance”, “bushy Brow” and “bristly Sides”, as well as unoriginal “rugged Cliffs” and at their base the “gay Carpet of yon level Lawn”.[4]

Within the same year the poet was able to mine out of it the unencumbered and swiftly moving text which is chiefly remembered today.[5] This was written in a four-stressed line of seven or eight syllables rhymed in couplets or occasionally triple rhymed. Geoffrey Tillotson identified as its model the octosyllabics of Milton’s “L'Allegro” and of Andrew Marvell’s “Appleton House”, and commented that he “learns from Milton the art of keeping the syntax going”.[6] He could also have mentioned that Marvell had employed the same metre in the shorter “Upon the Hill and Grove at Billborrow”,[7] which takes its place in the line of prospect poems stretching from John Denham’s “Cooper’s Hill” (1642) through Dyer to the end of the 18th century.[8]

Dyer’s poem differs from most of these in that it is shorter, no more than 158 lines, and more generalised. Although the hill itself and the River Towy are named in the poem, the old castles on the neighbouring heights are not, nor is their history particularised. Instead they are made an emotional image and given Gothic properties:

-

- Tis now the raven’s bleak abode;

- Tis now th’apartment of the toad;

- And there the fox securely feeds;

- And there the pois’nous adder breeds,

- Conceal’d in ruins, moss and weeds.”

- Conceal’d in ruins, moss and weeds.”

- And there the pois’nous adder breeds,

- And there the fox securely feeds;

- Tis now th’apartment of the toad;

- Tis now the raven’s bleak abode;

From this contrast with their former glory, the poet says that he learns to modify his desires and be content with the simple happiness that his presence on the hill brought in the past and continues to do. The drawing of a moral is more a private affair, in the same way that the poet’s contentment is a sincere personal response to the natural scene, rather than made the occasion for public lesson-drawing – still less is it, as in the case of the several later parson poets that adopted other hills, used for professional admonitions from their pulpit.

The different professionalism that Dyer brought to the poem was that of his recent training in painting. The “silent nymph, with curious eye” addressed at the start watches the evening “painting fair the form of things”. She is called to aid her “sister Muse” in a dialogue where poetry and painting cross-fertilise each other:

-

- Grongar Hill invites my song,

- Draw the landskip fair and strong.

- Draw the landskip fair and strong.

- Grongar Hill invites my song,

‘Landskip’ was by then an art term and is soon partnered by others from the professional vocabulary: “vistoes” (line 30) and “prospect” (line 37). Authorial music is subdued by this place “where Quiet dwells” and “whose silent shade [is] for the modest Muses made”. The effects are predominantly visual, as in the description of how perception of the surrounding natural features is modified on ascending the hill slope (lines 30–40), or in the likening of the contrasting aspects of the view to “pearls upon an Ethiop’s arm” (line 113).

While the view is not minutely detailed, what Dyer sees from the summit is authentic, as is apparent from a comparison with the prose description in the guidebook already quoted. But it is possible for the eye to be guided by the vision of the painters then in vogue. Among the influences on Dyer identified by critics have figured Claude Lorrain, Nicholas Poussin, and Salvator Rosa,[9] the latter of whom was, like Dyer, both a poet and painter. The mellow light effects of Dyer’s poem are certainly Claude’s, but without the Classical trappings. As a vista, with the abrupt ascent rising from the river in the foreground, leading to a view of distant towers, it approximates more closely to Rosa’s “Mountain Landscape”, now in Southampton Art Gallery.[10]

Another way in which Dyer’s poem differed from much that had gone before, and is prophetic of the change in sensibility to come, is its personal tone. What is drawn by him out of the landscape are not the gleanings of his bookshelf but reflections “so consonant to the general sense or experience of mankind, that when it is once read, it will be read again,” as Samuel Johnson observed.[11] In the words of a later commentator, his “gentle, quaintly precise moralizing is unlike the typical classical didacticism in that it seems to spring inevitably from the effect of natural objects on the poet's mind, instead of being itself a main thing and laboriously illustrated by such natural facts as came to hand.”[12] It was by means of such generalised humanism, says another, that Dyer “broke with tradition by making himself, as both poet and person, an object of study and contemplation.”[13]

The interest of the last two critics was in tracing the thread that leads from the neo-classicism of Dyer’s time to the personalised Romantic vision of nature. For William Wordsworth, in his sonnet addressed to the poet,[14] Dyer is rescued from the fashionable preference formerly given unworthier models by his ability to conjure up “a living landscape” that will ultimately be remembered “Long as the thrush shall pipe on Grongar Hill.” Here Wordsworth refers to the final lines of Dyer’s poem. But in fact the whole of it fits the Wordsworthian paradigm. At the very beginning, Dyer invokes the “sister muse” lying on the mountain top, as he had done himself in the past, to call up the memory of the scene. In this way the poem’s inward reflective quality reaches towards that “emotion recollected in tranquillity” which was Wordsworth’s own definition of the wellspring of poetry. “The emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.”[15]

3. A Landscape in Words

Among the other poems by Dyer that accompanied the first appearance of “Grongar Hill” in Savage’s miscellany was his epistle to his teacher Jonathan Richardson, “To a Famous Painter”, in which he modestly confessed that “As yet I but in verse can paint”.[16] After Dyer's death, it was included among his poems as a continual reminder that he had practised both arts. Richardson had been well known as an art theorist and the poetic practice of his apprentice was soon to be questioned by other theorists. William Gilpin, in his popularisation of the concept of the Picturesque, Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales, relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty (1782), found Dyer’s poetry deficient in that quality. “His distances, I observed, are all in confusion; and indeed it is not easy to separate them from his foregrounds.” And while the immediate detail of the passage beginning “Below me trees unnumber’d rise” (lines 57ff) was justly observed, it was perceptually wrong to discern in equal detail the ivy on the walls of Dinevawr Castle.[17]

Not all artists were so outspoken. In his textbook Instructions for Drawing and Colouring Landscapes (London, 1805), Edward Dayes returned to the same description of trees downhill that Gilpin cites as a correct middle ground. Though perhaps “it is too much detailed for any mass in a picture” in itself, he finds it commendable nevertheless as illustrating the principle that diversification of form and colour is needed in painting “to prevent monotony”.[18]

Bishop John Jebb appealed to other qualities in the text. The demand that a poet should keep to the single viewpoint of an observer is “no more than the objection of a mere painter. It is not the objection of a man of moral sensibility; for who would sacrifice for a technicism of art those specialities which...prepare us for one of the most touching applications in English poetry; for which, be it observed, had we been kept at a distance, according to the rules of perspective, we should not have been sufficiently interested spectators.”[19] Gilpin’s own nephew, William Sawrey Gilpin, sided with the bishop’s appeal in a theoretical work of his own. “Can the mind be pleased, nay delighted, without being interested?" he objected. “How different the estimation of an extensive prospect that suggested the beautiful reflections of the poet” in the passage beginning “See on the mountain’s southern side" (lines 114-28).[20]

For all that, the debate over the pictorial qualities of Dyer’s poem continued into the 20th century in much the same terms. Christopher Hussey, in his book The Picturesque: studies in a point of view (1927), finds in it a Claudian landscape “composed into a unity”, a claim dismissed by John Barrell in The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place (1972). For Barrell the poetic effects are random and the sense of place is disrupted by the way that “the eighteenth century poet is forever interrupting his scene-painting to find its moral or emotional analogue”. On the other hand, Barrell saw little difference between the approaches adopted by either Dyer or William Gilpin. Where the latter lingered over a landscape “according to whether it fulfilled or not his ‘picturesque rules’, the topographical poet chose his subject by its ability to furnish him with apt images to ‘moralize’.”[21]

Later still, Rachel Trickett exposed the “innate absurdity” of the supposition “that the technique Dyer acquired as a painter could be reproduced with a kind of transliterated accuracy in language.” Furthermore, it is a legitimate part of the poet’s role to comment and “Dyer does in fact make a distinction between the visual and the perceptual by separating his passages of description and of moralizing”.[22]

4. Tributes

Verse tributes to “Grongar Hill” have been somewhat oblique. The second stanza of the young William Combe’s “Clifton” names as among the forerunners of his own prospect poem Pope’s “Windsor Forest”; the “gentle spirit…who hail’d on Grongar Hill the rising sun”; and Henry James Pye’s “Faringdon Hill”.[23] Later Combe was to avenge William Gilpin’s insult to Dyer’s poem by caricaturing his work in The Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of the Picturesque.[24] Another youthful tribute to Dyer’s poem occurs at the start of Coleridge’s undergraduate squib “Inside the coach” (1791), which parodies the opening lines. In place of Dyer’s “Silent Nymph with curious eye! Who, the purple ev'ning, lie”, he invokes the “Slumbrous God of half-shut eye! Who lovest with limbs supine to lie” (lines 5–6) as he vainly seeks rest on a night journey.[25]

During the 19th century there were two translations of Dyer’s celebration of the Welsh countryside at the tail end of the Welsh literary renaissance. The first was the “Duoglott Poem, faithfully imitated” as Twyn Grongar by Rev. Thomas Davies in 1832.[26] A second, Bryn y Grongaer, was written by William Davies (1831–1892) under his bardic name of Teilo.[27] The site itself was painted early in the century by Henry Gastineau and later appeared as a woodcut in Wales Illustrated (1830).

Although the poem was frequently anthologised, it did not appear as an individual work (apart from in the Welsh duoglott translation) until the scholarly edition of C. Boys Richard (Johns Hopkins Press, 1941). This was accompanied by a topographically incorrect woodcut taken from Dodsley’s 1761 collection of Dyer’s poems showing a riverside mansion at the steep foot of a castled hill.[28] There were, however, several limited small press editions. These included the hundred copies from the Swan Press (Chelsea) in 1930;[29] one illustrated with woodcuts by Pamela Hughes (1918–2002) from the Golden Head Press (Cambridge, 1963) ;[30] and two editions including other poems from the Grongar Press (Llandeilo, 1977, 2003) with woodcuts by John Petts.[31]

The poem’s most devoted artistic admirer has been John Piper, who described it as “one of the best topographical poems in existence because it is so visual.” He first painted the hill in 1942[32] and the oil was subsequently issued as a coloured print.[33] Later he produced three lithographs for the edition issued by the Stourton Press (Hackney, 1982). This used the much rarer original version in pindarics.[34]

The Piper print was also redeployed as the CD cover of a setting of Dyer’s words by the Welsh composer Alun Hoddinott, who knew the area well in his youth. In 1998 he took four stanzas from the pindaric version of the poem and set them for baritone and string quartet with piano as “Grongar Hill” (Op.168). He also set other sections in 2006 for soprano, baritone and four hands at the piano, titling it “Towy Landscape” (Op. 190). The work is in the form of a dramatic ‘scena’ which is subdivided into recitative and aria-like sections.[35]

References

- Modern Antiquarian http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/10698/gron_gaer.html

- Dyfed Archaeology, Llangathen http://www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk/HLC/HLCTowy/area/area192.htm

- Thomas Rees, The Beauties of England and Wales, London 1815, vol.18, p.328 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=J64vAAAAYAAJ

- See the text online http://spenserians.cath.vt.edu/TextRecord.php?textsid=38003

- Google Books, pp.214–19 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=sNgIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA214

- ”Grongar Hill” in Augustan Studies (1961) pp.184–203 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5btMAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA184

- Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/48331

- Geoffrey Grigson, “Hill Poems” in The Shell County Alphabet, Penguin 2009 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=PivvoAlKfNQC&lpg=PT288

- Laurence Goldstein, Ruins and Empire: The Evolution of a Theme in Augustan and Romantic Literature, University of Pittsburgh 1977, p.31 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SYCxq5oAV1kC&lpg=PA31

- Art UK https://static.artuk.org/w800h800/HMPS/HMPS_SCAG_1_1961.jpg

- “Dyer” in Lives of the Poets http://www.gutenberg.org/files/4678/4678-h/4678-h.htm#link2H_4_0015

- Myra Reynolds, The treatment of nature in English poetry between Pope and Wordsworth, University of Chicago 1909, p.105 https://archive.org/stream/treatmentofnatur00reynrich#page/n130/mode/1up

- Bruce C. Swaffield, Rising from the Ruins: Roman Antiquities in Neoclassic Literature, Cambridge Scholars 2009, ch. 4, “The artist’s ‘landskip’ as a paradigm for Pre-Romantic poetry” https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=LQUaBwAAQBAJ&lpg=PA25

- “To the poet, John Dyer” http://www.bartleby.com/145/ww425.html

- Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, paragraph 26 http://www.bartleby.com/39/36.html

- The Works of the English Poets, vol.53, pp.135–37 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=B7EDAAAAQAAJ&lpg=PA135

- Observations on the River Wye etc, London 1782, pp.101–06 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433067371702;view=1up;seq=150

- The Works of Edward Dayes, London 1805, pp.305–6 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=QXxbAAAAQAAJ

- Charles Forster, The Life of John Jebb, London 1836, vol.1, p.176 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2fg5AAAAcAAJ

- Practical Hints Upon Landscape Gardening, London 1832, pp.31–2 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=O5hgAAAAcAAJ

- Barrell, The Idea of Landscape, Cambridge University 1972, pp.34–6 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4N8BrJ34Qa0C&lpg=PA12

- ”Some Aspects of Visual Description” in Augustan Studies, University of Delaware 1985, pp.241–2 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OQzMRuvOkZEC&lpg=PA241

- Clifton (Bristol 1775), p.2 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=HgoVAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA1

- Images at the British Library https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-tour-of-doctor-syntax

- George Watson, Coleridge the Poet, London 1966, p.49 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ERJqDAAAQBAJ&lpg=PA49

- Grongar Hill, a duoglott poem, Llandovery 1832 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=X7FYAAAAcAAJ

- Quoted in William Samuel, Llandilo Past and Present, Carmarthen 1868, pp.27–31 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=dXoHAAAAQAAJ

- Ebay photos http://picclick.ca/Wales-Welsh-Poet-Poetry-Poems-Grongar-Hill-John-391664442524.html#&gid=1&pid=2

- 8vo Details: 8vo printed on hand-made paper, vignette illustration on titlepage, linen spine with paper label, patterned paper-covered boards http://www.besleysbooks.com/books/4053.html

- Two illustrations in The Private Library 5/4, Cambridge 1964, pp.61, 65 http://www.plabooks.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Journals-vol_5_number_4_206.pdf

- Illustration at Abe Books https://www.abebooks.co.uk/Grongar-Hill-Poems-Dyer-John-Press/4160691245/bd

- Preparatory study at the Derek Williams Collection at the National Museum of Wales https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=JjGRJP3eylsC&pg=PA49&lpg=PA49

- Details on Ebay http://picclick.co.uk/Grongar-Hill-Carmarthen-John-Piper-print-in-10-131985617588.html#&gid=1&pid=1

- Details https://pallantbookshop.com/product/grongar-hill

- Jeremy Huw Williams, “Alun Hoddinott – a singer’s perspective”, in Alun Hoddinott: A Source Book, Ashgate 2013, pp.x-xi https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eN2hAgAAQBAJ