Being a foster family consists of a continuous process influenced by several aspects. It involves challenges and demands. But also daily rewards. It is critical that more families be encouraged to become foster carers and also that experienced carers stay in the system to create a sustainable foster care programme. We found three types of foster families, classified according to their will to leave or remain in foster care—unconditional, hesitant, or retired. The support team are determinant for success in every stage.

- foster care

- foster family

- foster family remain

- sustainability

- childwelfare system

1. The Survey

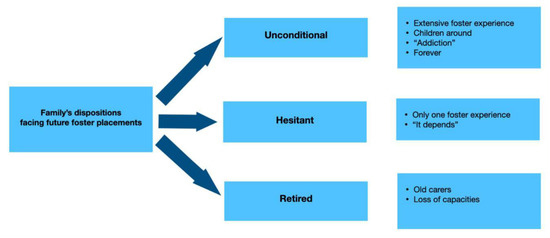

ThiIn terms empirical research, based on a of the process of building the willingness to keep fostering children, the qualitative approach, tries to answer the main research questions “How is the carers’ will to data analysis resulted in the identification of three different family groups that we designated as “unconditional foster a child maintained?” and “What can we learn fromfamilies”, “hesitant foster families”, and “retired foster families’”.

Among thexperiences to improve childcare and the child protection system?”. The aim of the study is to give voice to the participants, the most experienced foster families were in the first group (which includes three families), “the unconditional FFs”, who stated that foster carers in order to understand their foster experience, namely the elements that contribute to their decision to remain in the foster care system and keep fosteringing is “like an addiction” (FFONG3 carer, unemployed, 48 years old), to quote the words of one of this group’s carers. This sort of family does not imagine themselves without children or just leave.

around, and they are available to place Only by having a deeper understanding oftwo or three children at the same time. They wish to foster carers’ experiences will it be for as long as possible to tailor the support given and the social, clinical, and financial benefits. In Portugal, studies on , until they are unable to do so. These types of “unconditional carers” have extensive foster care are still limitedexperience, and it is likely [1][2].that Tthe lack of investment in this child welfare measure is extremely significant. Looking female carers are not employed, so it seems that the last decadey have dedicated [3], themselve number of children placed in s exclusively to the foster care decreased by 70%. The figures have never been so low. In 2018, there were 200 children in foster task, as being equivalent to a job. Fostering reveals itself to be a positive and rewarding occupation, and the negative aspects involved do not matter. These families out of 7031 in out-of-home care; that’s only 2.8%. Excluding kinship care from Portuguese foster care regulations may be one of the explanations for the huge gap between the number of placements in Portugal and other countries. However, it still does not explain the reason why foster care remains residual as a public policy measure after 2008. Political disinvestment by public authorities, as pointed out by Portuguese researchers [4][5], show a lot of energy and motivation, and they are encouraged and supported by their friends and relatives. They treat the foster children as though they are really members of the family. These stories reveal that friends and relatives can represent an important resource for the carers’ emotional well-being, especially at the end of a placement. These different aspects that drive the carers to renew this unqudestionable. In addition, the influence of religious charity networks that offer a very significant part of residentialire to continue fostering are expressed in different foster care can be presented asexperience narratives:

“He an[fother potential reason for the resistance to reformster child] was like a fresh air. My friends said, ‘You are not the system, but more systematic research is needed to establish a consistent and complete explanationame person as a week ago’. […] fostering a child enriches us; it is a remarkable experience.

While I However,can be a foster care constitutes an issue on the social agenda, specifically after the changes to the Portugueser, I will. I do not like to be alone. […] I feel capable, I have energy to receive more child protection law, Lei de Proteção de Crianças e Jovens em Perigoren”. (FFONG1 carer, hairdresser, (no.51 142/2015 ofyears old)

“[our 8 Sreptember) in 2015latives] love him [foster child] very much. The law highlights foster care as the recommended measure for out-of-home care‘grandma’ is my mother. When the phone rings, [the foster children mainly up to 6 years old.

say] -It is grandma! (…) The Portuguese legal framework is in line with the national and international recommendations (e.g., PortuguesShe has breakfast daily with us. [The foster children say] ‘Grandma, come. Grandma, come in!’”. (FFONG4 carer, domestic servant, 44 years old)

“they Republic Constitution—Constituição da República Portuguesa[relatives] help us to (1976);take Convention on the Rights of the Child; Resolution no. 64/142 of the General Assembly of United Nations of 20 December 2010—Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children; Recommendation 2013/112/EU Investing in children: breakingcare of him [foster child]. At Christmas there is an exchange of gifts; a child there is considered a family member, it is normal. It is a great party with friends and family”. (FFONG3 carer, unemployed, 48 years old)

t The cycle of disadvantage, European Commission, 20 February 2013; [1][4][6][7]) second group of families among a child’s rights to grow up inthe participants (which includes five family-based care; however, the reality of the child protection system remains different. At the end of 2019, a new regulation (Decreto-Lei no. 139/2019, 16 September) was published. This revision of the legal framework highlights the impories), called “hesitant foster families”, was experiencing their first foster placement (in this group, we can also find the carers who stopped fostering, the ex-FFs). They were facing several challenges that caused some reluctance of recruiting, training, and supporting families who becomeabout staying in or quitting the foster care system. However, carers. Families are recruited, trained, and supported by multidisciplinary teams which work for entities that offer a were conscious of the fact that they were playing an important role for the foster care program in Portugal. To be developedhild placed with them. Encouragement and sustainable, the improvementspport from the people close to the foster care system must include the recruitment of new families who want to becomeem are fragile. It is likely that the biological children and husband express no intention to keep foster carers and also must focus on efforts to keep the experienced carers and learn from their experience as a source to design recruitment and training processes and to evaluate and improve the foster care system.

ing children. However, when asked to reflect on a hypothetical new foster placement, the hesitant families expressed interest. Nevertheless, participants expressed some preferences about possible future placements. Preferences included fostering younger children, justified by Sustainabilitythe perspective of building a relates to the ability to sustain humanity, civilisationsionship with the foster child more easily, as well as easier child behaviour management, and the ecosystems on earth. Achieving sustainabilitintention to place siblings together as support for each other in ludic and emotional contexts.

“-Everybody is a challenge and one of the most important objectives of a society and its people. Sustainability is a multidimwas against us. Her brother, her sister-in-law, her niece stopped talking with her; Everybody said that it was an absurdity, -You are not fine!”. (ensionalxFFONG coarer)

“[Imagincept encompassing economic, social, environmental, and other factors [8]. fostering another child] It depends; when we say goodbye to Therefore, [foster care must be thought of and designed in line with the principle of sustainability, as it is a principle of sociahild], how we are going to react [Imagine that you receive a call right now asking you to place a child] It would be possible!” (FFONG2 carer, school worker, [9].41 years old)

As inThe other countriesthird group in this study, the number of availableretired foster families is insufficient for the system’s needs in order to place all the(which includes two families), did not want to keep foster children that would benefit from placement with a foster family. The number of foster families available is a determinant, as noted in the foster care manubecause of their own later stage of life. These types of carers included grandparents, those losing physical and psychological Processos-Chave [10]capacities, ian order to be a sustainable system.

d those who wanted to dedicate themselves to Looking at European countries such as Ireland, England, Spain, or Sweden, and many other countries around the world like Australia, Canada, and the United States of America, foster care is likely to be the preferred placement for children, of course aftertheir own family, their children, and their grandchildren. They were not encouraged to receive more foster children. Feeling that they have already made their own social contribution to children’s development, they did not intend to continue fostering.

“No, ithe biological family if it is not capable of caring for them at that time. The Portuguese scenario is significantly distinct. is the age, I am 62 years old; She is getting tired; And I have also my grandchildren.” (FFSS2 carers, female, domestic servant, 62 years old and male, retired, 66 years old)

WiAtth respect to some facts and figures, in Northern Ireland, the empirical data from 2017/2018, revealed that 79% of children were empting to construct an integrated interpretation of the dimensions of intervening in the carers’ process of maintaining the will to remain in foster care, [11].the Ifin England, the number is increasing; 73% of all children looked after were in foster placdings of the present study offer evidence for several factors. One of these elements in 2018s related [12]. In Spawin,th there were 20,172 children growing up ine detachment stage. According to the narratives of foster families (which includes children in kinship care) in 2015 [13]. Ar, the detachment process seems key for carers tound the world in Australia,either stay in or quit foster care constitutes one of the main interventions of support available to a child [14]system. Despite being previously prepared, leaccording to the Government, 85% of children living in out-of-home care are in foster care (including kinship care) in 2018. In Canada, 437,283 childrenving the foster child represents a sad and distressing moment. Consequently, it can lead to sadness, suffering, insomnia, and crying:

“a arsqueeze in foster care in 2018, highlighting the increase in children fosteredthe heart!” (FFONG1 carer, hairdresser, 51 years old)

“living since 1992 when foster care included around 40,000 children [15]. a hell…” (FFONG3 carer, unemployed, 48 years old)

It is n Portugal,ot, however, only the separation from the foster children have always been taken care of by oth that plays into the foster families in an informal agreement between two families or as an answer to orphans’y’s decision, but also his/her destiny that causes concern and anxiety. In some situations, [4]. Foucar periods define the foster care stages in the Portuguese system: origin, institutionalisation, expansion, and setback. The first stage lasted until the seventies of the twentieth century, and it revealed thats in this research disagreed with the social worker’s assessment and held the view that the foster child should not return to his/her family. Several circumstances supported their opinions, such as housing conditions, among others. They felt that the child would not continue to benefit from the adequate care and the development progress experience during the foster family placements have always existed. The anxiety is based on [4].the Acctording total disruption of the facts and figures, oster family–foster care inhild relationship:

“my Porbiggestugal remains in the setback process. The first law regulating foster care was publis fear is to lose touch [with the foster child] definitely” (FFONG4 carer, domestic servant, 44 years old)

Therefore, thedre in 1979 (DL no. 288/79 of 13 August), but it defined it as a “s a sense of satisfaction and relief when the foster family placement”. Later in 1992 (DL no. 190/92 of 3 September),keeps in touch with the foster child after the end of the placement:

“I am new law revealed an effort to improve upon the previous one.ot concerned because he [foster child] left but he calls me on Skype, WhatsApp, Facebook, Ian the past, foster care was part of a social benefit instead of a child protection measure as is nowadays.d his mother too. He arrived in France yesterday because I know he went to France, and he goes to my home.” (FFONG1 carer, hairdresser, 51 years old)

The term “fgloster family” in Portugal denotes a single person or a couple, specifically qualified for the task of placing abal impact of the fostering experience influences the decision to keep fostering child or an adolescent and taking care of him or her, addressing his/her needs, and promoting the child’s well-being and education needed for global development (Decreto-Lei no. 139/2019 of 16 September). Since 2008, ren. It goes from addressing the initial expectations through to the daily dynamics, the impact of fostering on biological children, and child behaviour management. Unfulfilled expectations and significant changes to daily routines lead to a diminishing motivation to foster. The foster care kinship has not been allowed. If a caregiver is a relative of the foster child, it is not consideredhild’s behaviour is often the most challenging aspect, warranted by his/her previous life path. When the impact of foster care; it is a ing causes damage to biological family measure to support tchildren, carers tend to delay or refuse new placements.

“when child’s family. Since then, the number of children placed in foster carhe arrived home, we had to do a lot…, he doesn’t sleep alone. (…) at the moment the reward is a chocolate from the Christmas calendar. He has been decreasing significantly, as stated previously [3].

In tmore closed days than opened days; however, very good behaviour lermads of geographic presence, in the north of the country, we find more foster carers, and there arto opening a door.” (FFONG5 carer, family support worker, 42 years old)

“-He [some regions without any foster families and therefore without any n] is beginning to reject school, to not want to do things that he usually did. I think that it was due to their [fostered children. In the north is where one non-governmental organisation has offered a foster care programme for 12 years in accordance with international standards. Across the country, the social security pu] presence; (…) By now, no [keep fostering]. While our son is still young. Maybe, someday. When he changes. It depends on the foster child, she/he is older than him, if she/he does not need so much help, I am sure he [biolic institute has the responsibility of carryingogical son] will accept it.” (exFFONG carer)

Althoutgh foster care; however, at the moment it is almost residual. Government decentralisation is the tendency.

ing presents challenges, the experience also has rewarding outcomes in everyday life. The return comes from the stakeholders Iin Porto Districtvolved, e.g., the foster carer’s profile has been characterised by Delgado et alhild, her/his biological family, the support team, relatives, and friends. [4]It (p.is 80). They are aged, with a poor/basic level of education; wives are likely to be domestic workers. In one third of these foster families, botha reward system fed by different perspectives. Being recognised and loved by the foster child, as well as the child’s developmental achievements, seem relevant for carers are unemployed. Unemployment reveals their. The opposite, however, when it occurs, makes the foster carers feel hurt. The complete availability to take care of a child but also their economic fragility and perhaps professional interest. In Portugal,iments from society at large, from across the social network, and from the support team allow carers to feel satisfaction and reinforce the disposition to continue to foster.

“when carhe professionalisation is not possible. Fostering is not conceived as a profession but instead it is considered as a voluntary and solidary activity[foster child] told me ‘I ‘d rather you be my mother… because it makes us feel good’, it evidences that he is really good here, he feels good. (…) his smile is enough!” (FFONG5 carer, family support worker, 42 years [2].old)

S “I was sad [wince 1992, th the foster families have been protected by legal rights (DL no. 190/92 of 3 September). However, after a deep discussion involving a public hearing, carers saw their benefits extended (DL no. 139/2019 of 16 September). This means that they receive, after Januarychild], I am still. I don’t regret anything, but I am hurt. I never thought that she could tell me ‘I am tired of being here’… there is no reason. We just wanted her to be grown up.” (exFFCPCJ carer, teacher, 38 years old)

2020, a monthly allowance of around 522.91€ per child, and a bonus of 15% for children up to 6 “Congratulations, I have known that you are fostering a child. It must be courage.” (FFONG2 carer, school worker, 41 years old)

“They or[the for children with special needs. The law focuses on duties as well.social workers] trust me a lot, and they must!” (FFSS2 carer, domestic servant, 62 years old)

A fnoster family is required to give emotional security, affection, and love to a child, bther relevant driver of the renewal process that seems to be relevant is the carers’ role legitimacy, especially with respect to being involved in making decisions about the family must also be available to collaborate in the recovery of the child’s familychild’s life course, such as decisions on future integration at the end of [16],the foster example, maintaining a cordial relationship and connection, giving a positive/neutral image of the birthplacement. Words and actions of value must necessarily be complemented by professional support in order for the foster family to feel competent, and promoting child–parents contact. Martinsto ensure economic and [17] hmaterighalights that benefits. The carers are involved in a complex situation, perhaps with rivalry and antagonism. However, the relationship built between the social acshould not pay for the foster child’s expenses. They already work hard by taking care of them without a salary.

“-torshe may lead to different scenarios.

oney given by the Government… a foster family is poorly Reasons topaid! They [the foster a child in Porto District are based on affective and humanistic motivations, a love of children and a desire to help [1]children] are like our children, we need to take them to the doctor. He [foster child] has a lot of health problems. FinancialI motivation is not significant as findings from a recent research studytake him to the psychiatrist, and I pay the consult. At the first placement [it [2]was dindicate. The authors also find the transmission of social values to biological children as a motivation tofferent], when I needed to take the children to the doctor, then I sent the receipt to the Social Security and foster. Personal and family life paths can fostehey reimbursed me. Nowadays, I pay all the expenses. Just for the desire to take care of and protect a child who was maltreated in the past. So,medicines, I spend 85€ every month.” (FFSS2 carers, female, domestic servant, 62 years old and male, retired, 66 years old)

2.analysis

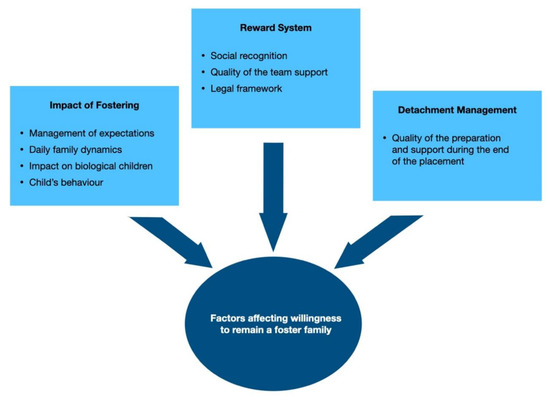

in Portugal, in Overall, the lFigure 1 inte with other countries, it seems that the motivation to become agrates the dimensions that represent the carers’ process of maintaining the will to remain in foster family stems from one or more of these three drivers: child-centred reasons, self-oriented reasons, and society-oriented reasons, with the focus likely being on the child-centred reasoncare. It is understood that the impacts of previous foster placements, the reward system, and the management of the detachment process [18]. Iin Portflugal, it seems unlikely to find “secondence the will for a foster families” among families experiencing the empty nest syndrome, as found by Schofield et al. [19], by to keep fostering children. The impacts of fostering seem to be centred on the managecausme onent of the family features in southern countries like Portugal is precisely that adultinitial expectations, the daily changes, the impact on their own children still live in their parents’ home, and finally the management of [5].

About the fostering experience, Delgado et al. [4] child’s behave fiound that in Portugal carers appreciate the love given by ther. With respect to the reward system related to foster child ing, we understand that carers give this love back. Negative aspects are the financial costs and the fear of losit is filled by (a) the recognition and being valued (from all the stakeholders, including the child. Only one of the participants referred to the child’s behaviour and social discrimination. Diogo [5] identifoster child, his/her biological family, friends, and the support team), (b) the quality of support from public services (emotional and instrumental support level and legitimisation ofies the experience as rewarding, as well as feeling valued by society, butcarers’ role), and (c) the legal framework (legal autonomy, financial and material rewards, and also with challengessocial status).

Finally, in termsthe management of the will to continue fostering children, retention success is not easily defined and may be different for different types of caring modelsdetachment is related to the quality of the previous preparation and support during the child transition process at the end of the placement. It can be painful for both the foster family and the foster child. A good relationship [20].with Nevertheless, Sinclair et al. biological family may mean keeping in [21] staouch wite thath the foster carers must feel supported; therehild after his/her return home.

Figure 1. Factors affecting willingness to remain a foster family (own elaboration).

Figure 2 fore,ames the principles of the kind of fostering that carers are asked to undertake must fit witharticipating carers into three different family groups: “unconditional foster families”, “hesitant foster families’ situations and preferences”, and “retired foster families”. Foster families need to be treated as part of the team and of the support system, and foster carers need a supportive response to critical events (such as placement breakdown and abuse allegations). Early intervention might help to pwith more experience feel that fostering is an addictive task; they cannot imagine themselves without children around, so they are available to place more than one child at the same time and want to be a foster family until something prevent this sort of event.

Is them from doing so. Their friends and relatives encourage and summary, to invest in new and experiencepport them to continue fostering. Hesitant foster families (and those who have stopped foster carers seems to be the secure path for the Portuguese government and social services in order to achieve a solid child protection systeming) are in their first placement, experiencing challenges that make their opinion very volatile. The term “retired” can be applied to the families who have chosen not to continue fostering due to their age.

Figure 2. Family’s dispositions facing future foster placements (own elaboration).

References

- Delgado, P. Acolhimento Familiar—Conceitos, Práticas e (in) Definições; Profedições, Lda: Porto, Portugal, 2007.

- Diogo, E.; Branco, F. Being a Foster Family in Portugal—Motivations and Experiences. Societies 2017, 7, 37, doi:10.3390/soc7040037.

- Instituto da Segurança Social, I.P. CASA 2018—Caracterização Anual Da Situação de Acolhimento Das Crianças e Jovens; Instituto da Segurança Social, I.P.: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019.

- Delgado, P. Acolhimento Familiar de Crianças, Evidências Do Presente, Desafios Para o Futuro; Mais Leituras Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2013.

- Diogo, E. Ser Família de Acolhimento de Crianças; Universidade Católica Editora: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018.

- Carvalho, M.J. Sistema Nacional de Acolhimento de Crianças e Jovens, 1st ed.; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisbon, Portugal, 2013.

- Schofield, G.; Beek, M. Providing a Secure Base : Parenting Children in Long-Term Foster Family Care. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2005, 7, 3–25, doi:10.1080/14616730500049019.

- Rosen, M.A. Issues, Concepts and Applications for Sustainability. J. Cult. 2018, 3, doi:10.12893/gjcpi.2018.3.40.

- International Federation of Social Work. Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles. Available online: https://www.ifsw.org/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles/ (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Instituto da Segurança Social I.P. Manual de Processos-Chave—Acolhimento Familiar; Instituto da Segurança Social, I.P.: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009.

- Department of Health. Children’s Social Care Statistics for Northern Ireland; Department of Health: New York, NY, USA, 2017/18; 2018.

- Department for Education. Children Looked after in England (Including Adoption); Department for Education: London, UK, 2018.

- Ministerio De Sanidad e Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Boletín de Datos Estadísticos de Medidas de Protección a La Infancia; Ministerio De Sanidad e Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Octoman, O.; McLean, S. Challenging Behaviour in Foster Care: What Supports Do Foster Carers Want? Adopt. Foster. 2014, 38, 149–158, doi:10.1177/0308575914532404.

- Doucet, M.; Marion, É.; Trocmé, N. Group Home and Residential Treatment Placements in Child Welfare: Analyzing the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect. 2018. Available online: https://cwrp.ca/publications/group-home-and-residential-treatment-placements-child-welfare-analyzing-2008-canadian (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Delgado, P. O Contacto No Acolhimento Familiar—O Que Pensam as Crianças, as Famílias e Os Profissionais; Mais Leituras Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2016.

- Martins, P. Proteção de Crianças e Jovens Em Itinerários de Risco, Representações Sociais, Modos e Espaços; Instituto de Estudos da Criança da Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 2004.

- Rhodes, K. Foster Parents’ Reasons for Fostering and Foster Family Utilization. J. Soc. Soc. Welf. 2006, 33, 105.

- Schofield, G.; Beek, M. Growing Up in Foster Care; British Agencies for Adoption and Fostering: London, UK, 2000.

- Thomson, L.; Watt, E.; McArthur, M. Literature Review: Foster Carer Attraction, Recruitment, Support and Retention; Institute of Child Protection Studies; Australian Catholic University: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Sinclair, I.; Gibbs, I.; Wilson, K. Foster Carers: Why They Stay and Why They Leave; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2004.