There is increasing focus on the difficult challenge of realizing coordinated development of production, living and ecological spaces within the regional development process. An ecological–production–living space (EPLSs)evaluation index system was established in this study based on the concept of EPLSs and the relationship between land use function, land use type and the national standard of land use classification, to reveal the driving forces and patterns of variation in EPLSs in Inner Mongolia.

- ecological space, production space, living space

- ,land use

- ,driving force

1. Characteristics of EPLS in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015

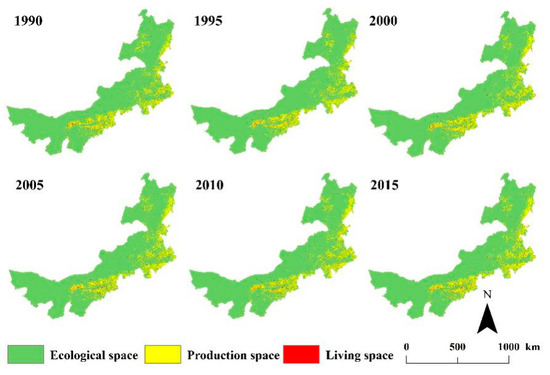

TFigure 1 shere haows been a gradual increase in tension between people and land as sthe spatial structure has become increasingly unbalanced,distribution of ecological, living and production space has become inefficient and living spaces and the ecological environment have gradually deteriorated. Ls of Inner Mongolia for six different periods from 1990 to 2015. Grassland is the basis of human civilization, and at a macro scale, there are three general categories of residential space [1]. Sdominant land use type in Inner Mongolia due to the prevaince havling undergone reform and joining the global community, China has achieved widely recognized industrialization and urbanization achievements. However, this progress has also resulted in a series of sustainable development challenges. There have been increasing conflicts and contradictions between production, living andclimate, topography and other natural conditions. The proportions of production, ecological and living spaces in Inner Mongolia in 2015 were approximately 10.18%, 88.79% and 1.03%, respectively and ecological space was the priority. The ecological spaces. The 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposed the concept of construction of Inner Mongolia is mainly distributed in the grassland and hilly areas to the north of three categories of living spaces, namely ecological, production and living spaces (EPLSs), defined as ecological space that is left unspoiled, space reserved for intensive and efficient e Greater Hinggan–Yinshan–Helan mountains, with a spatial distribution roughly inverse to that of living and production, and living space that is sufficient in size and conducive to human well-being, respectively.

spaces. The production space of Inner Mongolia is mainly distributed to The conceptthe south of these three categories of living spaces has become increasingly prevalent in related academic research and practice since Greater Hinggan–Yinshan–Helan mountains, with that of the Hulunbeier Caoyuan and Alxa Desert area being proposed (Figure 1). Arelathough this concept is rarely used internationally, there have been related studies on regional or urban functional space, including the Linear City Theory proposed by Arturo Soria, a Spanish engineer and urban plannerively small and basically consistent with the boundary zone of animal husbandry and agriculture in Inner Mongolia. The main reason for the relatively small production space in Inner Mongolia [2][3],is the Garden City Theory proposed by Ebenezer Howard in the United Kingdomue to its location to the north of [4] and the Othrganic Decentralization Theory proposed by Eliel Saarinen, a Finnish–American architect [5]. Glee mountains in an area in which soil, precipitatiobaln urban development began to face new challenges after the mid-20th century, during which the constrand temperature conditions are not suitable for large-scale production of large cities expanded significantly and urban problems have become more prominent. Consequently, there has been increasing research on urban growth borders, regulation of green belts and other related fields. At the same time, thereactivities. The living spaces of the Hubaoe urban agglomeration in the central part of the Inner Mongolia, Chifeng and Tongliao areas in the east are relatively concentrated.

Figure 1. Spatial distributions of production, living and ecological spaces in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015.

2. Spatial Patterns of EPLS in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015

2.1. Changes to Spatial Extent of EPLS

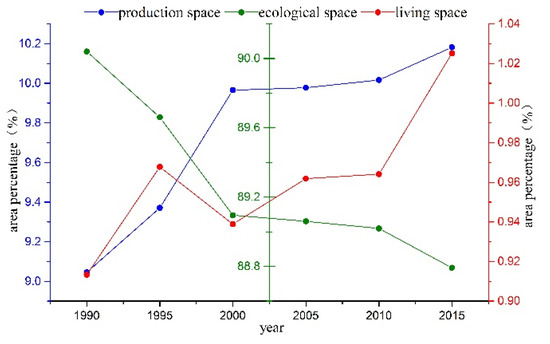

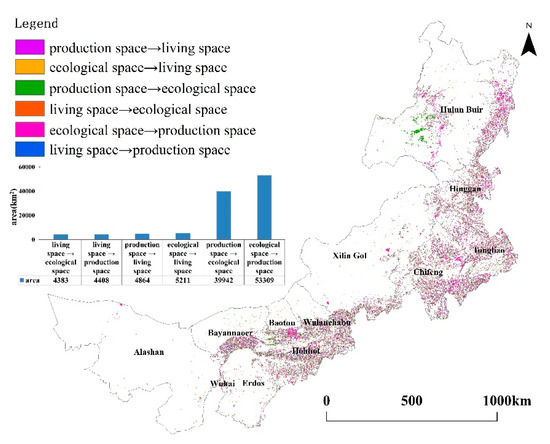

Figure 2 shaows been an increasing focus onthe changes in coverage of production, living and ecological and environmental problems encountered during the process of urban development and the realization that protection of the spaces in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015. It is evident that there was a dramatic decline in ecological environmental plays an important role spaces in Inner Mongolia from 103.14 × 104 km2 in urban1990 constructto 101.74 × 104 km2 ion and development. In summary, whil2015, declining by 1.36% over the studies on urban functionaly period, whereas living and production spaces and multifunctional land use outside of China have rarely used the three living spaces categorization to define regionalincreased by 12.27% and 12.59% over the study period, respectively.

Figure 2. Percentage changes to the areas of production, living and ecological spaces in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015.

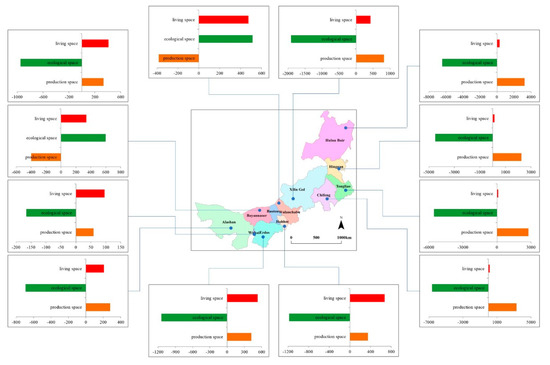

or urban functi Figure 3 shonal spacews, these studies have many similarities with studies in China that have utilized the three living spaces categorization. Studies on living spaces in China started relatively late compared to internat the spatial changes in EPLS for the 12 leagues of Inner Mongolia over the period 1990 to 2015, in which there are obvious regional studies, and within the context of a planned economy, there was an excessive emphasis in China on productiondifferences. Among the 12 league cities in Inner Mongolia, only Ulanqab and Bayannur showed increases to the extent of ecological space, whereas other spatial functions in the regiondecreasing trends were largely ignored. Subsequent to China rejoinievident in the remainder. Among the global community, reform of the economic system resulted in increasing attention onm, the cities of Chifeng and Hulunbeier showed the largest declines, reaching 6636 and 6436 km2, recological functions. Thus, relevant studies based on the recognition of three categories of livingspectively. Hohhot, Ordos and Ulanqab showed the greatest increases in ecological spaces hav at 672, 531 and 474 km2, re bspecome popular within geography. Chinese scholars have since conducted a lot of research related to ecological,tively, whereas the city of Wuhai had the smallest increase at 96 km2. pProduction and living spaces (EPLSs), and have achieved considerable research insights.

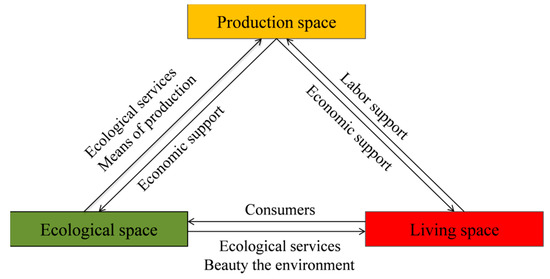

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram representing the relationships between ecological, production and living spaces (EPLSs).

space in Bayannur and Ulanqab decreased by 400 and 383 km2 Rresearch on EPLS has mainly focused on two aspects. The first is research on the connotatiopectively, whereas increases were evident in the city of Hulunbeier, the league of Hinggan and definition of EPLS. Although the increasing focus on land uthe cities of Tongliao and Chifeng of 3297, 2247, 2766 and 3297 km2, respe/land cover change (LUCC) research has resulted in varying interpretations of EPLS among different scholars, they have all proposed theoretical frameworks based on the spatial structure and the functively. In general, living spaces in the central and western regions increased, ecological spaces decreased and production of land use. While there has been a large amount of empirical research,spaces in the eastern region increased.

Figure 3. Spatial changes to ecological, production and living spaces (EPLSs) in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015. The unit in the bar charts is km2.

2.2. Shifts in the Spatial Center of Gravity of EPLS in Inner Mongolia

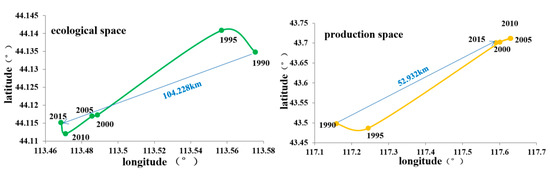

there remains no unified definition and classification standard for EPLS [6]. The second The center-of-gravity transfer traspjectory of EPLS research relates to the evolution and drivers of EPLS. While there have been many studies on the spatial patterns of EPLS, the majority of these studied the evolution andin Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015 was calculated using the center transfer formula, with the results shown in driversFigure 4. of EPLS verItically, with insufficient attention focused on the core elements during the is evident that the center of gravity of EPLS development process. There is clearly a need for research to characterize the evolution and drivers of EPLSs [7].

Ecoloin Inner Mongolia changed from 1990 to 2015. The center of gravical, production and ty of living spaces are not isolated and are clearly closely related and influence each other. P showed the greatest migration, whereas that of production space is a fundamental driving force which provides economic support for living andshowed the smallest. The trajectory of the center of gravity of ecological spaces. Efficient use of production space optimizes industrial structure, promotes social and economic development and ultimately facilitates quality of life and the maintenance in Inner Mongolia showed an “S” shape from 1990 to 2015, and the center of gravity of ecological space for humans as well as for other organismsmoved 104.228 km to the southwest, with the migration not obvious from 1990 [8][9][10].to The2010, ultimate goal of coordinated and optimized development of EPLSs is to maintain the well-being of residents, and the realization of this goal is mainly reflected inbut accelerating subsequently. Over the same period, the center of gravity of production space in Inner Mongolia moved 52.932 km to the northeast, whereas that of living space. Ecological space is the foundation moved 190.509 km to the southwest.

Figure 4. Migrations of production, living and ecological space in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015 as calculated using the Barycenter migration model. Blue arrows indicate the moving distances.

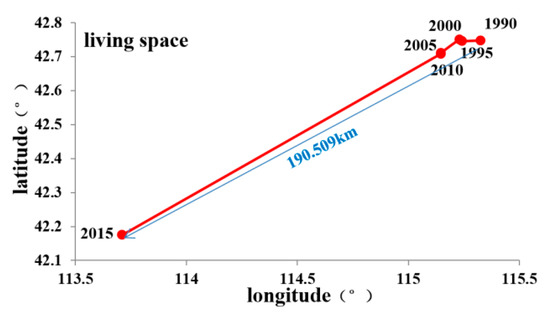

2.3. Characteristics of Mutual Transformation of EPLS in Inner Mongolia

Figure 5 shofws EPLS, and the support of livingthat the interaction between ecological space and production space for the realization of their own functions is the key to coordinating thewas the most obvious, with a clear, consistent relationship between human development and land, and even to realizing regional sustainable developmentecological space and production space, [11]. Twhe ecological space provides ecosystem goods and services, for example, natural water purification, and ensures stable development of the region. At the same time, the quah was concentrated in the cities of Hulunbuir and Chifeng, indicating poor stability of the eecological space is directly affected by living and production spacand living spaces in this region. In general, changes [12].

to EPLS is a paradigm under which people can protect and utilize nature to realize their own development and reflects the ability of humans to transform nature and their own development level. The division of space withinn Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015 were mainly concentrated in the area south of the Xingan Ling–Yinshan–Helan mountains, where the main production mode was agriculture. In other words, the relative stability of the EPLS is intuitive and easy to identify. The identification and description of the internal drivers of spatial development is of great significance. An imbalance within EPLS is an important driver of environmental pollution, frequent disasters, over exploitation of energy resources and degradation of ecosystem functions. The bottom-up implementationarea was consistent with that of areas in which animal husbandry is practiced. There were obvious impacts of agricultural-based production methods on changes to EPLS.

Figure 5. Transformation in ecological, production and living spaces (EPLSs) in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2015.

of a spatial development strategy is needed to mainta Several features were noted within the coordinated developmentspatial patterns of EPLS, with measures adjusted for local conditions and based on science and the coordination of the contradiction between prote in Inner Mongolia. The changes in EPLS indicate that there have been rapid increases in production and development.

EPLS lin Chvina currently faces many challenges. The eg spaces, whereas ecological space has undergones have continual erosion, resulting in an imbalance between ecological and urban ously decreased. Within structural EPLS change, living spaces. The extensive use and poor management of production space has resulted in serious environmental pollution. There is currently an imbalance in the supply structure of have always been focused within towns, with a strong path dependence characteristic, whereas production spaces are mainly distributed bordering living spaces, and development remains insufficient and unbalanced. The current study focused on the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region that is characterized by a fragile and sensitive ecological environment. A classificaeven appear to be an expansion of the “enclave”-type space in which living and production system was established for EPLS in Inner Mongolia based on land use data for 1990 to 2015. Spatiotemporal variations in EPLS were analyzed and driving forces ofpaces are nested and distributed within an ecological space, with the evolution of EPLS were identified. It is hoped that the results of the present study can provide a reference for rational utilization of land and coordinated development of EPLSs to facilitate sustainable development within Inner Mongoliacological space constantly fragmented by living and production spaces, and the degree of fragmentation becoming increasingly severe.