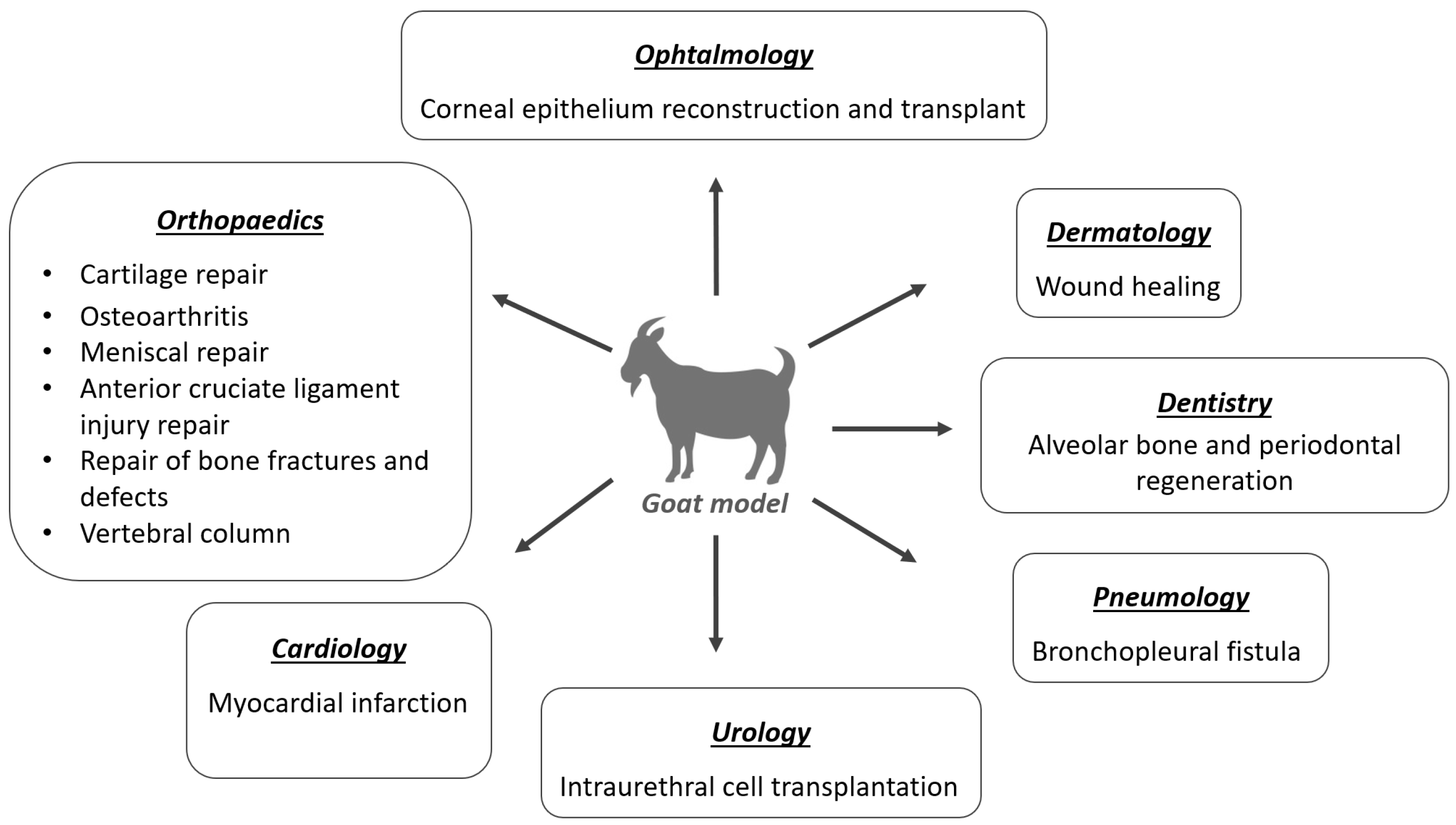

This topic aims to compile the works published in the scientific literature, over the last two decades, that use the goat as an animal model in preclinical studies using stem cells, alone or associated with biomaterials, for the treatment of injury or disease in divers organ systems. Stem cells can be classified as embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which differ in origin, plasticity, differentiation potential, and risk of tumorigenesis. MSCs have been the most studied cells, with excellent and safe results in multiple areas. In the area of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, the caprine model is particularly used in studies using stem cells in the musculoskeletal system but, although in a more limited way, also in the field of dermatology, ophthalmology, dentistry, pneumology, cardiology, and urology.

- mesenchymal stem cells

- caprine model

- MSCs

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are undifferentiated cells of non-hematopoietic origin, with self-renewal capacity, located in various adult or extra-embryonic tissues. These cells are classified as multipotential, meaning they are capable to differentiate into multiple cell lines, namely cardiomyocytes, chondroblasts, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, myocytes, neuronal cells, osteoblasts, and tenocytes, among others [1,2][1][2]. MSCs can be obtained from embryonic cells in the first stages of embryo development before its implantation in the uterus, and in adults, they can be isolated from various tissues, such as umbilical cord, placenta, amnion, bone marrow (BMSCs), adipose tissue (ASCs), dental pulp and periosteum [37,38,39][21][22][23]. The diversity of sources of stem cells or MSCs and the wide range of potential applications of these cells lead to a challenge in selecting a suitable cell type for cell therapy [8]. In veterinary medicine, MSCs are collected mainly from bone marrow (BM) or adipose tissue (AT), since these tissues are easier to obtain [2,4,40][2][4][24]. Depending on how MSCs are obtained, therapy with these cells can be autologous, if they are obtained from the same animal, allogeneic if the donor is another individual from the same species, or xenogeneic if the donor is from a different species. Regarding the route of administration, they can be applied locally, systemically, generally intravenously, or both, depending on the disease [37][21]. These cells have the ability to differentiate into the target cell type allowing the regeneration of the injured area and also have great immunomodulatory potential. This immunomodulation is due to paracrine effects (by secreting different cytokines and growth and differentiation factors (GDFs) to adjacent cells) and by cell-to-cell contact, leading to vascularization, cell proliferation in injured tissues, and reducing inflammation [1,6,37,41][1][6][21][25]. Different diseases in animals have been treated using cell-based therapy, mainly to regenerate damaged tissue or reduce inflammation. These cells are considered “immune privileged” as they do not express histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and costimulatory molecules (such as CD40, CD80, and CD86), allowing allogeneic therapy, as they escape the recognition and action of T cells and NK receptors [1,2,6,42][1][2][6][26]. MSCs can be applied in a wide range of clinical specialties, such as traumatology and orthopedic, ophthalmology, neurology, internal medicine, dermatology, and immunopathology, among others. Figure 1 shows the medical specialties studied for MSCs therapy in the goat model. The applications of these therapies in the veterinary medicine field include not only their clinical use in domestic animals, but also the translation of the results, as a preclinical model, for human medicine [14]. These cells show great resistance to cryopreservation, allowing the creation of cell banks for later use and the selection of the best donors by previously evaluating their MSCs in vitro [2].

3. Application of MSCs in the Goat Model

3.1. Orthopedics

3.2. Dermatology

3.3. Ophthalmology

3.4. Dentistry

3.5. Pneumology

3.6. Cardiology

3.7. Urology

References

- Dias, I.E.; Pinto, P.O.; Barros, L.C.; Viegas, C.A.; Dias, I.R.; Carvalho, P.P. Mesenchymal stem cells therapy in companion animals: Useful for immune-mediated diseases? BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 358.

- Jiménez, A.; Guerrero, F. Células madre mesenquimales como nueva terapia en dermatología: Conceptos básicos. Rev. Clínica Dermatol. Vet. 2017, 9, 8–18.

- Ogliari, K.S.; Marinowic, D.; Brum, D.E.; Loth, F. Stem cells in dermatology. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 286–291.

- Arnhold, S.; Elashry, M.I.; Klymiuk, M.C.; Wenisch, S. Biological macromolecules and mesenchymal stem cells: Basic research for regenerative therapies in veterinary medicine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 889–899.

- Spencer, N.D.; Gimble, J.M.; Lopez, M.J. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Past, present, and future. Vet. Surg. 2011, 40, 129–139.

- Peroni, J.F.; Borjesson, D.L. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Activities of Stem Cells. Vet. Clin. N. Am.-Equine Pract. 2011, 27, 351–362.

- Mastrolia, I.; Foppiani, E.M.; Murgia, A.; Candini, O.; Samarelli, A.V.; Grisendi, G.; Veronesi, E.; Horwitz, E.M.; Dominici, M. Challenges in Clinical Development of Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells: Concise Review. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 1135–1148.

- Rajabzadeh, N.; Fathi, E.; Farahzadi, R. Stem cell-based regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Investig. 2019, 6, 18.

- Harding, J.; Roberts, R.M.; Mirochnitchenko, O. Large animal models for stem cell therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 23.

- Gugjoo, M.B.; Amarpal; Fazili, M.U.R.; Shah, R.A.; Mir, M.S.; Sharma, G.T. Goat mesenchymal stem cell basic research and potential applications. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 183, 106045.

- Almarza, A.J.; Brown, B.N.; Arzi, B.; Ângelo, D.F.; Chung, W.; Badylak, S.F.; Detamore, M. Preclinical Animal Models for Temporomandibular Joint Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng.-Part B Rev. 2018, 24, 171–178.

- Harness, E.M.; Mohamad-Fauzi, N.B.; Murray, J.D. MSC therapy in livestock models. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac012.

- Polejaeva, I.A.; Rutigliano, H.M.; Wells, K.D. Livestock in biomedical research: History, current status and future prospective. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2016, 28, 112–124.

- Hotham, W.E.; Henson, F.M.D. The use of large animals to facilitate the process of MSC going from laboratory to patient—‘Bench to bedside’. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2020, 36, 103–114.

- Thomas, B.; Bhat, K.; Mapara, M. Rabbit as an animal model for experimental research. Dent. Res. J. 2012, 9, 111.

- Alvites, R.D.; Branquinho, M.V.; Sousa, A.C.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Mendonça, C.; Atayde, L.M.; Maurício, A.C. Small ruminants and its use in regenerative medicine: Recent works and future perspectives. Biology 2021, 10, 249.

- Maass, A.; Kajahn, J.; Guerleyik, E.; Guldner, N.W.; Rapoport, D.H.; Kruse, C. Towards a pragmatic strategy for regenerating infarcted myocardium with glandular stem cells. Ann. Anat. 2009, 191, 51–61.

- Liao, B.; Deng, L.; Wang, F. Effects of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells enriched by small intestinal submucosal films on cardiac function and compensatory circulation after myocardial infarction in goats. Chin. J. Reparative Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 20, 1248–1252.

- An, Y.H.; Friedman, R.J. Animal Selections in Orthopaedic Research. In Animal Models in Orthopaedic Research; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 39–57. ISBN 9780429173479.

- Madeja, Z.E.; Pawlak, P.; Piliszek, A. Beyond the mouse: Non-rodent animal models for study of early mammalian development and biomedical research. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2019, 63, 187–201.

- Dias, I.E.; Cardoso, D.F.; Soares, C.S.; Barros, L.C.; Viegas, C.A.; Carvalho, P.P.; Dias, I.R. Clinical application of mesenchymal stem cells therapy in musculoskeletal injuries in dogs—A review of the scientific literature. Open Vet. J. 2021, 11, 188–202.

- Klingemann, H.; Matzilevich, D.; Marchand, J. Mesenchymal stem cells—Sources and clinical applications. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2008, 35, 272–277.

- Webster, R.A.; Blaber, S.P.; Herbert, B.R.; Wilkins, M.R.; Vesey, G. The role of mesenchymal stem cells in veterinary therapeutics—A review. N. Zeal. Vet. J. 2012, 60, 265–272.

- Ayala-Cuellar, A.P.; Kang, J.; Jeung, E.; Choi, K. Roles of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Tissue Regeneration and Immunomodulation. Biomol. Ther. 2019, 27, 25–33.

- Torres-Torrillas, M.; Rubio, M.; Damia, E.; Cuervo, B.; del Romero, A.; Peláez, P.; Chicharro, D.; Miguel, L.; Sopena, J.J. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: A promising tool in the treatment of musculoskeletal diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3105.

- Quimby, J.M.; Borjesson, D.L. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in cats: Current knowledge and future potential. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 20, 208–216.

- Freitag, J.; Bates, D.; Boyd, R.; Shah, K.; Barnard, A.; Huguenin, L.; Tenen, A. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of osteoarthritis: Reparative pathways, safety and efficacy—A review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 230.

- Reissis, D.; Tang, Q.O.; Cooper, N.C.; Carasco, C.F.; Gamie, Z.; Mantalaris, A.; Tsiridis, E. Current clinical evidence for the use of mesenchymal stem cells in articular cartilage repair. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2016, 16, 535–557.

- Shukla, A.; Choudhury, S.; Chaudhary, G.; Singh, V.; Prabhu, S.N.; Pandey, S.; Garg, S.K. Chitosan and gelatin biopolymer supplemented with mesenchymal stem cells (Velgraft®) enhanced wound healing in goats (Capra hircus): Involvement of VEGF, TGF and CD31. J. Tissue Viability 2021, 30, 59–66.

- Pratheesh, M.D.; Gade, N.E.; Nath, A.; Dubey, P.K.; Sivanarayanan, T.B.; Madhu, D.N.; Sreekumar, T.R.; Amarpal; Saikumar, G.; Sharma, G.T. Evaluation of persistence and distribution of intra-dermally administered PKH26 labelled goat bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells in cutaneous wound healing model. Cytotechnology 2017, 69, 841–849.

- Pratheesh, M.D.; Dubey, P.K.; Gade, N.E.; Nath, A.; Sivanarayanan, T.B.; Madhu, D.N.; Somal, A.; Baiju, I.; Sreekumar, T.R.; Gleeja, V.L.; et al. Comparative study on characterization and wound healing potential of goat (Capra hircus) mesenchymal stem cells derived from fetal origin amniotic fluid and adult bone marrow. Res. Vet. Sci. 2017, 112, 81–88.

- Azari, O.; Babaei, H.; Derakhshanfar, A.; Nematollahi-Mahani, S.N.; Poursahebi, R.; Moshrefi, M. Effects of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells isolated from Wharton’s jelly of caprine umbilical cord on cutaneous wound healing; Histopathological evaluation. Vet. Res. Commun. 2011, 35, 211–222.

- Yang, X.; Qu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Hua, J.; Shi, M.; Moldovan, N.; Wang, H.; Dou, Z. Plasticity of Epidermal Adult Stem Cells Derived from Adult Goat Ear Skin. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2007, 74, 386–396.

- Holan, V.; Trosan, P.; Cejka, C.; Javorkova, E.; Zajicova, A.; Hermankova, B.; Chudickova, M.; Cejkova, J. A Comparative Study of the Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Limbal Epithelial Stem Cells for Ocular Surface Reconstruction. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 1052–1063.

- Zakirova, E.Y.; Valeeva, A.N.; Aimaletdinov, A.M.; Nefedovskaya, L.V.; Akhmetshin, R.F.; Rutland, C.S.; Rizvanov, A.A. Potential therapeutic application of mesenchymal stem cells in ophthalmology. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 189, 107863.

- Amano, S.; Yamagami, S.; Mimura, T.; Uchida, S.; Yokoo, S. Corneal Stromal and Endothelial Cell Precursors. Cornea 2006, 25, S73–S77.

- Joe, A.W.; Gregory-Evans, K. Mesenchymal stem cells and potential applications in treating ocular disease. Curr. Eye Res. 2010, 35, 941–952.

- Öner, A. Stem cell treatment in retinal diseases: Recent developments. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 48, 33–38.

- Banks, M.S.; Sprague, W.W.; Schmoll, J.; Parnell, J.A.Q.; Love, G.D. Why do animal eyes have pupils of different shapes? Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500391.

- Zhang, P.; Ma, X.-Y.; Huang, D.-T.; Yang, X.-Y. The capacity of goat epidermal adult stem cells to reconstruct the damaged ocular surface of total LSCD and activate corneal genetic programs. J. Mol. Histol. 2020, 51, 277–286.

- Yang, X.; Moldovan, N.I.; Zhao, Q.; Mi, S.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, D.; Gao, Z.; Tong, D.; Dou, Z. Reconstruction of damaged cornea by autologous transplantation of epidermal adult stem cells. Mol. Vis. 2008, 14, 1064–1074.

- Mi, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Qu, L.; Chen, S.; Meek, K.M.; Dou, Z. Reconstruction of corneal epithelium with cryopreserved corneal limbal stem cells in a goat model. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2008, 75, 1607–1616.

- Bansal, R.; Jain, A. Current overview on dental stem cells applications in regenerative dentistry. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, 29–34.

- Zou, D.; Guo, L.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, X. Engineering of bone using porous calcium phosphate cement and bone marrow stromal cells for maxillary sinus augmentation with simultaneous implant placement in goats. Tissue Eng.-Part A 2012, 18, 1464–1478.

- Bangun, K.; Sukasah, C.L.; Dilogo, I.H.; Indrani, D.J.; Siregar, N.C.; Pandelaki, J.; Iskandriati, D.; Kekalih, A.; Halim, J. Bone Growth Capacity of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells and BMP-2 Seeded into Hydroxyapatite/Chitosan/Gelatin Scaffold in Alveolar Cleft Defects: An Experimental Study in Goat. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2021, 58, 707–717.

- Marei, M.K.; Saad, M.M.; El-ashwah, A.M.; El-backly, R.M.; Al-khodary, M.A. Experimental Formation of Periodontal Structure around Titanium Implants Utilizing Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Pilot Study. J. Oral Implant. 2009, 35, 106–129.

- Khojasteh, A.; Eslaminejad, M.B.; Nazarian, H.; Morad, G.; Dashti, S.G.; Behnia, H.; Stevens, M. Vertical bone augmentation with simultaneous implant placement using particulate mineralized bone and mesenchymal stem cells: A preliminary study in rabbit. J. Oral Implantol. 2013, 39, 3–13.

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, T.A.; Wu, S.Y.; Lin, C.P.; Chang, H.H. Regeneration of Tooth with Allogenous, Autoclaved Treated Dentin Matrix with Dental Pulpal Stem Cells: An In Vivo Study. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1256–1264.

- Kunrath, M.; dos Santos, R.; de Oliveira, S.; Hubler, R.; Sesterheim, P.; Teixeira, E. Osteoblastic Cell Behavior and Early Bacterial Adhesion on Macro-, Micro-, and Nanostructured Titanium Surfaces for Biomedical Implant Applications. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2020, 35, 773–781.

- Chamieh, F.; Collignon, A.M.; Coyac, B.R.; Lesieur, J.; Ribes, S.; Sadoine, J.; Llorens, A.; Nicoletti, A.; Letourneur, D.; Colombier, M.L.; et al. Accelerated craniofacial bone regeneration through dense collagen gel scaffolds seeded with dental pulp stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38814.

- Zhang, W.; Walboomers, X.F.; Jansen, J.A. The formation of tertiary dentin after pulp capping with a calcium phosphate cement, loaded with PLGA microparticles containing TGF-β1. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.-Part A 2008, 85, 439–444.

- Hind, M.; Maden, M. Is a regenerative approach viable for the treatment of COPD? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 106–115.

- Petrella, F.; Toffalorio, F.; Brizzola, S.; De Pas, T.M.; Rizzo, S.; Barberis, M.; Pelicci, P.; Spaggiari, L.; Acocella, F. Stem cell transplantation effectively occludes bronchopleural fistula in an animal model. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 480–483.

- Seaberg, R.M.; Smukler, S.R.; Kieffer, T.J.; Enikolopov, G.; Asghar, Z.; Wheeler, M.B.; Korbutt, G.; Van Der Kooy, D. Clonal identification of multipotent precursors from adult mouse pancreas that generate neural and pancreatic lineages. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 1115–1124.

- Kruse, C.; Birth, M.; Rohwedel, J.; Assmuth, K.; Goepel, A.; Wedel, T. Pluripotency of adult stem cells derived from human and rat pancreas. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2004, 79, 1617–1624.

- Burdzinska, A.; Dybowski, B.; Zarychta-Wisniewska, W.; Kulesza, A.; Zagozdzon, R.; Gajewski, Z.; Paczek, L. The Anatomy of Caprine Female Urethra and Characteristics of Muscle and Bone Marrow Derived Caprine Cells for Autologous Cell Therapy Testing. Anat. Rec. 2017, 300, 577–588.

- Burdzinska, A.; Dybowski, B.; Zarychta-Wiśniewska, W.; Kulesza, A.; Butrym, M.; Zagozdzon, R.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; Radziszewski, P.; Gajewski, Z.; Paczek, L. Intraurethral co-transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and muscle-derived cells improves the urethral closure. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 239.