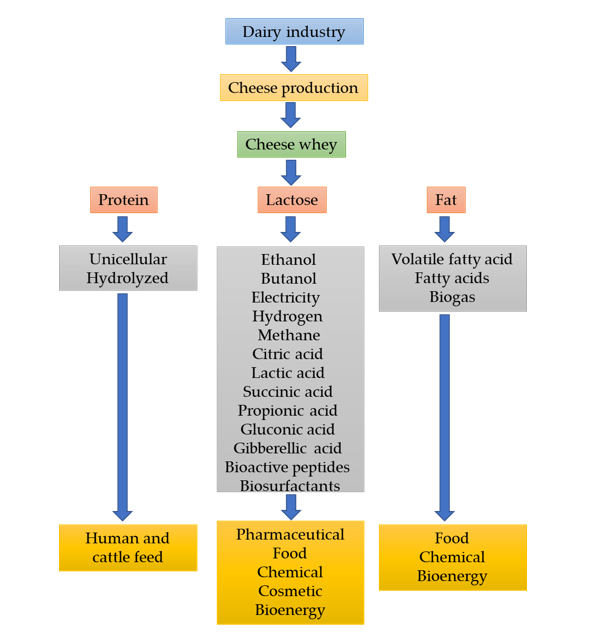

Agro-industrial residues such as bagasse, pomace, municipal residues, vinasse and cheese whey are an environmental problem around the world, mainly due to the huge volumes that are generated because of the food production to satisfy the nutritional needs of the growing world population. Among the above residues, cheese whey has gained special attention because of its high production with a worldwide production of 160 million tons per year. Most of it is discarded in water bodies and land causing damage to the environment due to the high biological oxygen demand caused by its organic matter load. The environmental regulations in developing countries have motivated the development of new processes to treat transform cheese whey into added-value products such as food supplements, cattle feed and food additives.

- bioenergy

- cheese whey

- bioethanol

- biohydrogen

- biomethane

- biodiesel

1. Introduction

2. Cheese whey-based biofuels

2.1 Bioethanol

Bioethanol production through fermentation has emerged as a potential alternative to replace fossil fuels such as gasoline. This renewable biofuel not only has application in the energy industry but is widely used as a replacement for chemical or grain-based ethanol in the cosmetic, pharmaceutical, food and beverage industries [11]. It has been reported that bioethanol production from corn and sugarcane has been produced extensively by the United States and Brazil, respectively. Nevertheless, the use of the above two feedstocks increases the total production cost and compromises food security due to the high land use for these crops [12]. In this sense, different feedstocks such as different lignocellulosic biomass, starches, food wastes and agri-food residues have been used for bioethanol production. The use of cheese whey as a substrate to produce bioethanol through fermentation is economically competitive in comparison with substrates such as sugarcane, corn and lignocellulosic biomass. In addition, it is a residue, and its valorization represents several advantages in terms of sustainable development, such as a decrease in waste, and organic carbon recycling [13].

2.1 Biomethane

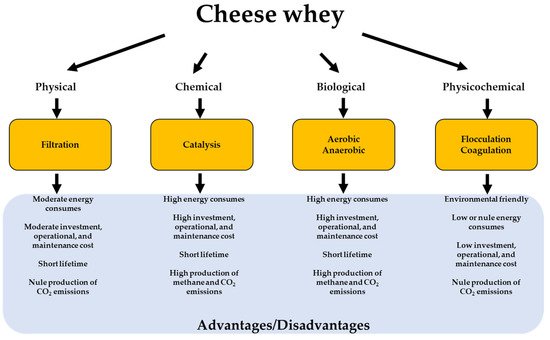

Methane is the one of most abundant biogas fractions produced by anaerobic di-gestion of organic residues, including cheese whey. As mentioned above, anaerobic di-gestion is a well know technology to produce methane. However, several challenges come with each specific feedstock that is used as a carbon source. These challenges can be classified into three main categories, microbiological, chemical, and operational, making anaerobic digestion one of the most complicated biological processes. Moreover, this technology is highly recommended to treat wastewater and residues with high biological oxygen demand, such as cheese whey [14]. Additionally, requirements related to the installation and operation of anaerobic biodigesters such as technology, energy consumption and space are relatively low. Nevertheless, depending on the re-actor type and feedstock the total cost can vary considerably. Likewise, the reactor type plays a key role during biogas production and classified the anaerobic digestion process into two different systems: low-rate system and high-rate system.

2.2 Biohydrogen

Methane is the one of most abundant biogas fractions produced by anaerobic di-gestion of organic residues, including cheese whey. As mentioned above, anaerobic di-gestion is a well know technology to produce methane. However, several challenges come with each specific feedstock that is used as a carbon source. These challenges can be classified into three main categories, microbiological, chemical and operational, making anaerobic digestion one of the most complicated biological processes. Moreover, this technology is highly recommended to treat wastewater and residues with high biological oxygen demand, such as cheese whey [14]. Additionally, requirements related to the installation and operation of anaerobic biodigesters such as technology, energy consumption and space are relatively low. Nevertheless, depending on the re-actor type and feedstock the total cost can vary considerably. Likewise, the reactor type plays a key role during biogas production and classified the anaerobic digestion process into two different systems: low-rate system and high-rate system.

2.3 Microbial lipids for Biodiesel

Biodiesel is one of the most popular biofuels produced due to is environmentally friendly and its net greenhouse emissions are lower in comparison with the produced from fossil fuels. Microbial lipid-base biodiesel production is one of the most promising biofuels due to its advantages (non-toxic, biodegradable, renewable, no sulfur content, high lubricity) in comparison with fossil diesel [15]. Microbial lipid-base biodiesel production is a potential alternative using low-cost residues such as cheese whey with high carbon content as a feedstock [16]. Table 1 shows a some of the research in biofuel production using cheese whey as a substrate.

Table 1

. Produced biofuels using cheese whey as substrate.

|

Substrate |

Strain |

Ethanol Concentration (g/L−1) |

Volumetric Productivity (g L−1 h−1) |

Reference |

|

Cheese whey (permeate) |

K. marxianus URM 7404 |

8.90 |

0.66 |

[17] |

|

Cheese whey (powder) |

S. cerevisiae |

23.80 |

nd |

[18] |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

K. marxianus URM 7404 |

25.81 |

2.57 |

[17] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substrate |

Inoculum |

Bioreactor |

Methane Yield |

Reference |

|

Cheese whey powder + vinasse |

Sludge from a poultry slaughterhouse |

AnSBBR |

11.5 molCH4 kg COD−1 |

[19] |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

Sludge from the wastewater treatment plant |

SBR |

340.4 L CH4 kg−1 CODfeed |

[20] |

|

Cheese whey powder |

Sludge from the wastewater treatment plant |

Anaerobic batch reactors |

0.266 L CH4 g CODconsumed |

[21] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substrate |

Strain |

Biohydrogen yield |

Biohydrogen productivity |

Reference |

|

Cheese whey (permeate) |

Microbial consortium |

3.60 mol H2/mol of lactose |

140.02 mmol H2/L day |

[22] |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

Clostridium sp. |

6.35 mol H2/mol lactose |

139 mL/g/h |

[23] |

|

Hydrolysed cheese whey |

Microbial consortium |

1.93 mol H2 mol−1 of sugars |

5.07 L H2 L−1 day−1 |

[15] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substrate |

Strain |

Total lipid (g/L−1) |

Lipid Accumulation (%) |

Reference |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

M. circinelloides URM 4182 |

1.06 |

22.5 |

[24] |

|

Deproteinized cheese whey |

C. oligophagum JRC1 |

5.64 |

44.12 |

[25] |

|

Ricotta cheese whey |

M. isabelline 1757 |

4.49 |

37 |

[26] |

|

Substrate |

Strain |

Ethanol Concentration (g/L−1) |

Volumetric Productivity (g L−1 h−1) |

Reference |

|

Cheese whey (permeate) |

K. marxianus URM 7404 |

8.90 |

0.66 |

[17] |

|

Cheese whey (powder) |

S. cerevisiae |

23.80 |

nd |

[18] |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

K. marxianus URM 7404 |

25.81 |

2.57 |

[17] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substrate |

Inoculum |

Bioreactor |

Methane Yield |

Reference |

|

Cheese whey powder + vinasse |

Sludge from a poultry slaughterhouse |

AnSBBR |

11.5 molCH4 kg COD−1 |

[19] |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

Sludge from the wastewater treatment plant |

SBR |

340.4 L CH4 kg−1 CODfeed |

[20] |

|

Cheese whey powder |

Sludge from the wastewater treatment plant |

Anaerobic batch reactors |

0.266 L CH4 g CODconsumed |

[21] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substrate |

Strain |

Biohydrogen yield |

Biohydrogen productivity |

Reference |

|

Cheese whey (permeate) |

Microbial consortium |

3.60 mol H2/mol of lactose |

140.02 mmol H2/L day |

[22] |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

Clostridium sp. |

6.35 mol H2/mol lactose |

139 mL/g/h |

[23] |

|

Hydrolysed cheese whey |

Microbial consortium |

1.93 mol H2 mol−1 of sugars |

5.07 L H2 L−1 day−1 |

[15] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Substrate |

Strain |

Total lipid (g/L−1) |

Lipid Accumulation (%) |

Reference |

|

Fresh cheese whey |

M. circinelloides URM 4182 |

1.06 |

22.5 |

[24] |

|

Deproteinized cheese whey |

C. oligophagum JRC1 |

5.64 |

44.12 |

[25] |

|

Ricotta cheese whey |

M. isabelline 1757 |

4.49 |

37 |

[26] |

References

- Castillo, M.V.; Pachapur, V.L.; Brar, S.K.; Naghdi, M.; Arriaga, S.; Ramirez, A. Yeast-driven whey biorefining to produce value-added aroma, flavor, and antioxidant compounds: Technologies, challenges, and alternatives. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 930–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388551.2020.1792407.

- Dinika, I.; Nurhadi, B.; Masruchin, N.; Utama, G.L.; Balia, R.L. The Roles of Candida tropicalis Toward Peptide and Amino Acid Changes in Cheese Whey Fermentation. Int. J. Technol. 2019, 10, 1533. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v10i8.3661.

- Fernández-Gutiérrez, D.; Veillette, M.; Giroir-Fendler, A.; Ramirez, A.A.; Faucheux, N.; Heitz, M. Biovalorization of saccharides derived from industrial wastes such as whey: A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 16, 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-016-9417-7.

- Ghasemi, M.; Ahmad, A.; Jafary, T.; Azad, A.K.; Kakooei, S.; Daud, W.R.W.; Sedighi, M. Assessment of immobilized cell reactor and microbial fuel cell for simultaneous cheese whey treatment and lactic acid/electricity production. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 9107–9115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.04.136.

- Tsolcha, O.N.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Akratos, C.S.; Bellou, S.; Aggelis, G.; Katsiapi, M.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Vayenas, D.V. Treatment of second cheese whey effluents using a Choricystis-based system with simultaneous lipid production. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 2349–2359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.4829.

- Lavelli, V.; Beccalli, M.P. Cheese whey recycling in the perspective of the circular economy: Modeling processes and the supply chain to design the involvement of the small and medium enterprises. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 126, 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2022.06.013.

- Verma, A.; Singh, A. Physico-Chemical Analysis of Dairy Industrial Effluent. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 1769–1775. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2017.607.213.

- Carvalho, F.; Prazeres, A.R.; Rivas, J. Cheese whey wastewater: Characterization and treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 445–446, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.038.

- De Jesus, C.-S.A.; Ruth, V.-G.E.; Daniel, S.-F.R.; Sharma, A. Biotechnological Alternatives for the Utilization of Dairy Industry Waste Products. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 06, 223–235. https://doi.org/10.4236/abb.2015.63022.

- Chandra, R.; Castillo-Zacarias, C.; Delgado, P.; Parra-Saldívar, R. A biorefinery approach for dairy wastewater treatment and product recovery towards establishing a biorefinery complexity index. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 1184–1196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.124.

- Das, B.K.; Kalita, P.; Chakrabortty, M. Integrated Biorefinery for Food, Feed, and Platform Chemicals. In Platform Chemical Biorefinery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 393–416, ISBN 978-0-12-802980-0.

- Saini, P.; Beniwal, A.; Kokkiligadda, A.; Vij, S. Evolutionary adaptation of Kluyveromyces marxianus strain for efficient conversion of whey lactose to bioethanol. Process Biochem. 2017, 62, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2017.07.013.

- Ky, I.; Le Floch, A.; Zeng, L.; Pechamat, L.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.L. Tannins. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 486–492, ISBN 9780123849533.

- Amani, T.; Nosrati, M.; Sreekrishnan, T.R. Anaerobic digestion from the viewpoint of microbiological, chemical, and operational aspects—A review. Environ. Rev. 2010, 18, 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1139/a10-011.

- Colombo, B.; Calvo, M.V.; Sciarria, T.P.; Scaglia, B.; Kizito, S.S.; D'Imporzano, G.; Adani, F. Biohydrogen and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) as products of a two-steps bioprocess from deproteinized dairy wastes. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2019.05.052.

- Ottaviano, L.M.; Ramos, L.R.; Botta, L.S.; Varesche, M.B.A.; Silva, E. Continuous thermophilic hydrogen production from cheese whey powder solution in an anaerobic fluidized bed reactor: Effect of hydraulic retention time and initial substrate concentration. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 4848–4860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.11.168.

- Murari, C.S.; Machado, W.R.C.; Schuina, G.L.; Del Bianchi, V.L. Optimization of bioethanol production from cheese whey using Kluyveromyces marxianus URM 7404. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 101182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101182.

- Zhou, X.; Hua, X.; Huang, L.; Xu, Y. Bio-utilization of cheese manufacturing wastes (cheese whey powder) for bioethanol and specific product (galactonic acid) production via a two-step bioprocess. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 272, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.10.001.

- Lovato, G.; Albanez, R.; Triveloni, M.; Ratusznei, S.M.; Rodrigues, J.A.D. Methane Production by Co-Digesting Vinasse and Whey in an AnSBBR: Effect of Mixture Ratio and Feed Strategy. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 187, 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-018-2802-7.

- Fernández, C.; Cuetos, M.; Martínez, E.; Gómez, X. Thermophilic anaerobic digestion of cheese whey: Coupling H2 and CH4 production. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 81, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.05.024.

- Novais, R.M.; Gameiro, T.; Carvalheiras, J.; Seabra, M.P.; Tarelho, L.A.; Labrincha, J.A.; Capela, I. High pH buffer capacity biomass fly ash-based geopolymer spheres to boost methane yield in anaerobic digestion. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.033.

- Romão, B.B.; Silva, F.T.M.; Costa, H.C.D.B.; Carmo, T.S.D.; Cardoso, S.L.; Ferreira, J.D.S.; Batista, F.R.X.; Cardoso, V.L. Alternative techniques to improve hydrogen production by dark fermentation. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1538-y.

- Patel, A.K.; Vaisnav, N.; Mathur, A.; Gupta, R.; Tuli, D.K. Whey waste as potential feedstock for biohydrogen production. Renew. Energy 2016, 98, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2016.02.039.

- Braz, C.A.; Carvalho, A.K.F.; Bento, H.B.S.; Reis, C.E.R.; De Castro, H.F. Production of Value-Added Microbial Metabolites: Oleaginous Fungus as a Tool for Valorization of Dairy By-products. BioEnergy Res. 2020, 13, 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-020-10121-y.

- Vyas, S.; Chhabra, M. Assessing oil accumulation in the oleaginous yeast Cystobasidium oligophagum JRC1 using dairy waste cheese whey as a substrate. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-019-1701-0.

- Carota, E.; Crognale, S.; D'Annibale, A.; Gallo, A.M.; Stazi, S.R.; Petruccioli, M. A sustainable use of Ricotta Cheese Whey for microbial biodiesel production. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584-585, 554–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.068.