Citrate is an intermediate in the “Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle” and is used by all aerobic organisms to produce usable chemical energy. It is a derivative of citric acid, a weak organic acid which can be introduced with diet since it naturally exists in a variety of fruits and vegetables, and can be consumed as a dietary supplement.

- citrate

- acid-base balance

- bone metabolism

- bone remodelling

- bone mineral density

- osteopenia

- osteoporosis

- kidney diseases

1. Introduction

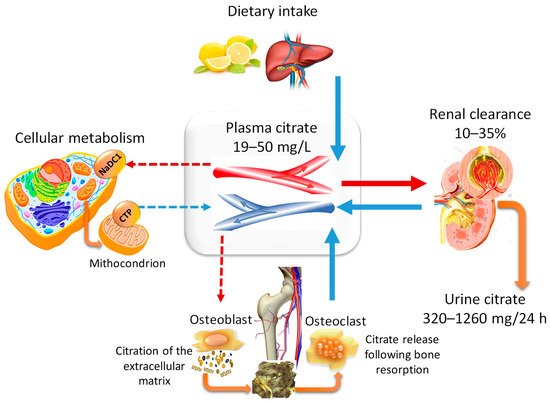

2. Citrate Homeostasis: General Physiological Concepts

2.1. The Pillars of Citrate Homeostasis

2.2. Citraturia as A Marker of Citrate Homeostasis and Bone Health Status

|

Cause |

Annotation |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Citrate and Bone Tissue

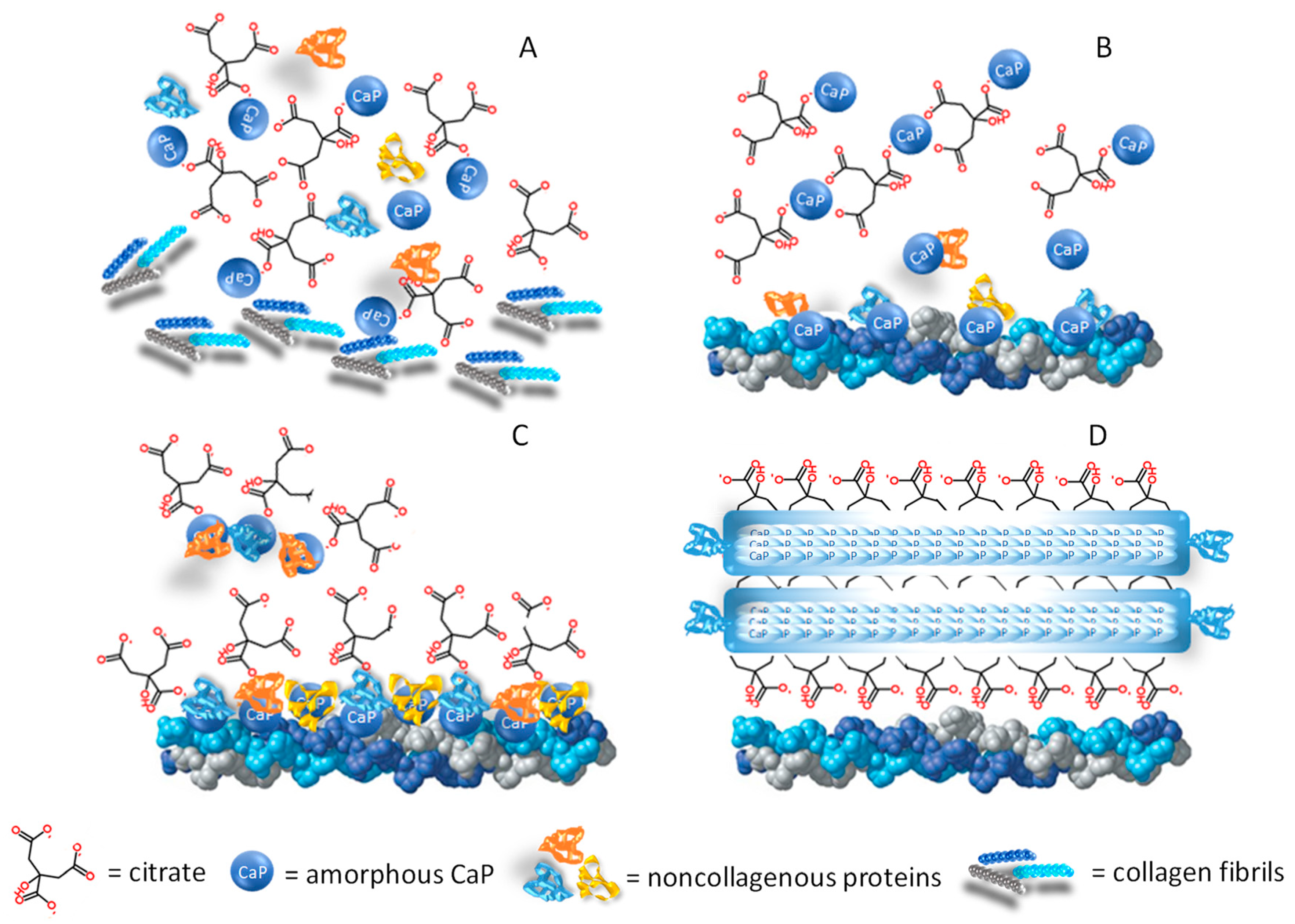

Over time, data in the literature regarding the relationship between citrate and bone physiology have been increasing exponentially, but the role of citrate in driving the structural and functional properties of healthy bone in humans has only been recently elucidated. Nowadays, there is adequate knowledge regarding changes in the citrate metabolism during the whole process of differentiation of the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into mature osteoblasts (Figure 2) [5][38][39] [5,53,56], how citrate enters the crystalline structure of bone, and how it controls the size and morphology of apatite nanocrystals (Figure 3) [40][41][42][43][44][38,40,43,44,45 ].

Taken together, studies regarding the role of citrate in the nanocrystal structure and those showing that osteoblasts were the specialised citrate-producing cells in bone have led to a new concept of bone formation related to “citration”. Briefly, Costello et al. (2012) stated that….”when considering the mineralisation role of osteoblasts in bone formation, it now becomes evident that ’citration’ must be included in the process. Mineralisation without ‘citration‘ will not result in the formation of normal bone, i.e., bone that exhibits its important properties, such as stability, strength, and resistance to fracture” [38][53].

Figure 2. Citrate metabolism, osteoblast differentiation, and mineralisation process. The figure combines the concept of “osteoblast citration” with the main steps of the differentiation of MSCs into bone-forming cells (osteoblasts). (A) Resting MSCs are quiescent, nonproliferating cells which exhibit the typical mitochondrial metabolism with the oxidation of citrate via the Krebs cycle. (B) In the presence of proper stimuli, the undifferentiated MSCs are committed to osteogenic differentiation and, at the early phase, high proliferation is required. To accomplish this goal, the following events are necessary: (1) the upregulation of the “zinc importer protein 1” (ZIP1), which promotes the zinc intake, (2) the accumulation of mitochondrial citrate due to the zinc-dependent inhibition of the mitochondrial aconitase, (3) the exportation of citrate into cytosol by means of the “citrate transport protein” (CTP/SLC25A1), (4) the use of cytosol citrate for the lipogenesis process which is essential for cell duplication. (C,D) The citrate exportation from cytosol to extracellular fluid starts during cell differentiation, and it is simultaneous with the synthesis and the release of amorphous CaP, collagen, and noncollagenous proteins. (E) The “osteoblast citration” is completed when the mineralised matrix is assembled. The role of citrate in growing the apatite nanocrystals and driving the mineralisation process is explained in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Citrate in the formation of the mineral matrix. (A) The amorphous calcium-phosphate (CaP) phase originates from an oversaturated CaP solution, and the mineralisation process starts when the organic phase (citrate, collagen fibrils, and noncollagenous proteins) is available in the bone microenvironment. (B) At the early stage, few citrate molecules bind with the amorphous CaP and the particle aggregation is slowed down. (C) In the next phase, the noncollagenous proteins released from bone cells favour CaP aggregation and apatite nucleation while the collagen promotes the self-assembly of CaP and guides the aggregate deposition on the collagen surface. (D) When the surface is fully covered by citrate, the thickness increase is inhibited (2–6 nm), while longitudinal growth continues up to 30–50 nm, thus explaining the flat morphology of bone mineral platelets. In addition, citrate forms bridges between the mineral platelets which can explain the stacked arrangement which is relevant to the mechanical properties of bone.

4. Citrate Pathophysiology and Bone Diseases

The role of citrate in mineralised tissues poses several questions regarding the consequences of a low bioavailability at the systemic level. For the most part, published data linking citrate alteration with bone metabolism refer to renal diseases, acid-base imbalance or also physiological conditions such as menopause, but there are also inheritable genetic defects which affect the TCA cycle in mitochondria or the citrate transport. In the following paragraphs, the medical conditions in which the association between citrate and bone health status has been implied are discussed.4.1. Bone Health Status and Alterations of Citrate Homeostasis in Kidney Diseases

With the progressive ageing of the population, epidemiological studies have shown a higher rate of elderly-related illnesses, including the impairment of bone quality leading to osteoporosis and decreased renal function with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which in turn may influence bone health status [45][46][47][66,67,68]. The decrease in renal function may be mild, moderate or severe on the basis of estimated-glomerular filtration rate (GFR) equations and is associated with the simultaneous impairment of mineral homeostasis, including serum and tissue concentrations of phosphorus and calcium, circulating levels of calciotropic hormones (PTH, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D), fibroblast growth factor-23, and growth hormone. The modifications of mineral homeostasis may promote a loss of bone mass and an increase in bone fragility [48][69]. As observed by Malmgren et al. (2015), approximately 95% of women over 75 years of age showed a mild-moderate decrease in renal function (CKD stages 2–3) which may have had a harmful effect on bone health [49][70]. In a 10-year longitudinal study, the authors evaluated the long-term influence of impaired renal function on bone mineral density (BMD) [50][71]. They analysed 1044 Caucasian women from the “Osteoporosis Prospective Risk Assessment” (OPRA) cohort and found that renal function was positively correlated with femoral neck BMD in elderly women, although the association attenuated as ageing progressed. Women with poor renal function had a higher annual rate of bone loss over 5 years compared to those with normal function, and markers of mineral homeostasis were more frequently altered. High-throughput “omics” approaches, including metabolomics, have been proposed to identify new biomarkers which could help the management of CKD patients, and TCA cycle-metabolites are emerging as potential candidates [51][72]. A significantly reduced urinary excretion of citrate (–68%) has been observed in non-diabetic patients with CKD as compared to subjects with normal renal function. The renal expression of genes regulating the TCA cycle was decreased in subjects who had impaired renal function, thus suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction could be involved in the pathogenesis of CKD [52][73]. Moreover, GFR positively correlated with citrate excretion, and kidney stone formers with CKD had significantly lower urinary citrate excretion than subjects with kidney stone disease and normal renal function [53][74]. To the researcheuthors’ knowledge, the link between CKD, urinary citrate and bone health status has still not been elucidated but, taking into account the information emerging from the previous paragraphs, it is reasonable to assume that the link exists. Some indications have derived from the data regarding kidney stone disease, which is the paradigmatic expression of a relationship between citrate alterations, BMD decrease and fracture risk that has been investigated since the 1970s [54][75]. In fact, several studies have shown that osteoporotic fractures occurred more frequently in patients with kidney stones than in the general population [55][56][57][58][76,77,78,79]. The connection between kidney stones and bone metabolism is related to several factors. Briefly, kidney stones form when urine becomes supersaturated with respect to its specific components. Since 80% of kidney stones are composed of calcium-oxalate (CaOx) or CaP, the regulation of calcium excretion plays a pivotal role in the etiopathogenesis of nephrolithiasis [59][80]. As urinary citrate is able to bind calcium and prevent the growth and agglomeration of CaOx and CaP crystals, the close relationship between low citrate excretion and kidney stone formation has been fully established [10][11]. The incidence of hypocitraturia varies from 20% to 60% in people who have a propensity to form stones, either as a single abnormality or in conjunction with other metabolic disorders [15][16]. Hypercalciuria may occur either when filtered calcium is abnormally increased or when its reabsorption is abnormally decreased. The former may be associated with enhanced bone resorption which raises calcium bioavailability at the systemic level, while the latter may be the consequence of decreased renal function as occurs in CKD. Theoretically, reduced GFR in CKD should lead to decreased urinary calcium concentration, but the consequences of defective tubular reabsorption are more relevant and are responsible for the supersaturation of calcium salts. In addition, in the distal nephron, calcium reabsorption is a PTH-dependent process, PTH being the hormone capable of stimulating the resorption of the bone matrix in response to low, systemic calcium availability [60][81]. Therefore, as the decrease in the renal function progresses, PTH levels and bone loss gradually increase, thus explaining why kidney stones are a significant predictor of osteoporotic fracture in patients with CKD [61][82]. Moreover, when nephrolithiasis occurs, patients are frequently advised to reduce calcium intake, thus favouring a negative calcium balance which is an additional risk factor promoting a decrease in BMD [10][11]. Recent findings have demonstrated that lithogenic risk factors, including hypocitraturia, are also detectable in patients without kidney stones who exhibit osteoporosis or osteopenia, thus leading to the hypothesis that the evaluation of lithogenic risk could have significant implications for monitoring bone health status [33][62][34,83].4.2. Postmenopausal Osteopenia and “Net Citrate Loss”

4.2. Postmenopausal Osteopenia and “Net Citrate Loss”

Estrogen deficiency and ageing are the main factors responsible for the depletion of bone mass [63][84], but they are also associated with changes in urine composition which are similar to those of subjects having an increased risk of kidney stones [10][11]. The circulating citrate levels and the citrate content in bone are markedly reduced in animals with age-related or ovariectomy-induced bone loss [64][85]. A low citrate excretion, less severe than true hypocitraturia fixed at less than 320 mg per day, has been described in postmenopausal women [10][32][11,33] and in subjects with a low bone mass [33][62][34,83]. Nurses’ Health Study II considered an ongoing cohort of 108,639 participants from whom information on menopause and kidney stones was obtained. In general, postmenopausal status was associated with lower BMD and a higher incidence of kidney stones in this cohort. Moreover, small but significant differences in urine composition were found in 658 participants who had pre- and postmenopausal 24-h urine analyses, including a lower citrate excretion [65][86]. The postmenopausal decline in estrogen concentration influences the activation rate of basic multicellular units composed of bone-resorbing osteoclasts and bone-forming osteoblasts. However, according to Drake et al., resorption increased by 90% while formation increased by only 45% [66][87] and the final result was a “net bone loss”. This imbalanced bone remodelling depends on the effects that the lack of estrogen has on bone cells. On the one hand, the activity of the receptor activator of the nuclear factor-κ B ligand (RANKL) is promoted, a key factor in osteoclast differentiation; on the other hand, the osteogenic precursors are destined to differentiate into adipocytes, and the survival of mature osteoblasts is suppressed [67][88]. The result is the reduction of mature osteoblasts, and since they are the cells capable of synthesising citrate [5], the consequence is lower citrate production which impairs the quality and the stability of the bone microarchitecture [40][41][38,40]. Moreover, osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption are energy-demanding processes, and the citrate which is synthesised cannot be accumulated because it is essentially utilised through the citric acid cycle [68][69][89,90]. Similarly, the MSC differentiation towards adipocytes requires more citrate as a source of cytosolic acetylCoA for lipid biosynthesis [64][85]. In conclusion, according to Granchi et al., estrogen deficiency leads to a “net citrate loss” which could explain the diminished citrate excretion observed in postmenopausal women [70][91].4.3. Genetic Variations Influencing Citrate Homeostasis and Skeletal Development

4.3. Genetic Variations Influencing Citrate Homeostasis and Skeletal Development

The “Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man®” database (OMIM®) is a comprehensive repository of information on the relationship between genetic variation and phenotypic expression [71][92]. The annotations connecting citrate homeostasis with skeletal defects are listed in Table 2, and many of these concern Slc proteins, which are a family of solute transporters through the membranes.|

Gene/Locus Name |

Gene/Locus |

Cytogenetic Location |

MIM Number: Phenotype |

Inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Solute carrier family 4, anion exchanger, member 1 (erythrocyte membrane protein band 3, Diego blood group) |

SLC4A1, AE1, EPB3, SPH4, SAO, CHC |

17q21.31 |

179800: Distal renal tubular acidosis |

Autosomal dominant |

|

Solute carrier family 4, anion exchanger, member 1 (erythrocyte membrane protein band 3, Diego blood group) |

SLC4A1, AE1, EPB3, SPH4, SAO, CHC |

17q21.31 |

611590: Distal renal tubular acidosis |

Autosomal recessive |

|

Glucose-6-phosphatase, catalytic |

G6PC, G6PT |

17q21.31 |

232200: Glycogen storage disease Ia |

Autosomal recessive |

|

Solute carrier family 13 (sodium-dependent citrate transporter), member 5 |

SLC13A5, NACT, INDY |

17p13.1 |

615905: Early infantile, epileptic encephalopathy, 25 |

Autosomal recessive |

|

Solute carrier family 12 (sodium/potassium/chloride transporters), member 1 |

SLC12A1, NKCC2 |

15q21.1 |

60167: Bartter syndrome, type 1 |

Autosomal recessive |

|

Claudin 16 (paracellin 1) |

CLDN16, PCLN1, HOMG3 |

3q28 |

248250: Renal hypomagnesemia 3 |

Autosomal recessive |