Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Vivi Li and Version 1 by bassam zidane.

Cracked teeth can pose a diagnostic dilemma for a clinician as they can mimic several other conditions. The constant physiological stress along with any pathological strain like trauma or iatrogenic causes can lead to the development of microcracks in the teeth. Constant exposure to immense stress can cause the progression of these often-undiagnosed tooth cracks to cause tooth fractures.

- cusp failure

- cracked tooth

- diagnosis

- enamel cracks

- imaging

- transillumination

- swept-source optical coherence Tomography

1. Introduction

A cracked tooth refers to a partial enamel rupture in a living tooth with dentinal and even pulpal involvement [1]. The causative factors of a tooth crack vary. A masticatory function is the most common factor related to vertical tooth fracture [2]. Depending on the crack’s extension depth and subsequent bacterial infections, cracked teeth can cause several clinical symptoms [3]. Typical symptoms include acute pain on chewing or unexplained pain as a result of exposure to a cold stimulus [4]. An incidence rate of 34–74% has been reported in adults between the ages of 30–50 [5], with a female predisposition [6,7][6][7]. The probability of a cracked tooth is higher in an aging population with a greater number of retained teeth [8]. There is an increase in the mineral density of enamel with aging. This is concurrent with a decrease in the volume of the protein matrix [9]. Cosmetic procedures such as bleaching can accelerate this deterioration in fracture toughness and mechanical properties of the enamel [10,11][10][11].

The mandibular molars are more susceptible to enamel fractures. Fractured enamel is more prevalent in the upper and lower bicuspids as well as the upper molar teeth [7]. The mesiopalatal cusp of the upper first grinder is quite protuberant. This creates wedging on the first mandibular grinders, which might also contribute to tooth cracks [12]. As a consequence, these teeth are more liable to fracture. Diagnosing a cracked tooth can be an arduous task for a clinician as its symptoms can be variable and bizarre [13]. The cracks will continue to spread if prompt treatment is not given. This can eventually lead to pulpitis or a complete tooth fracture [14]. The primary objective of its diagnosis is early detection. Visual inspection [15], periodontal probing, bite diagnosis, pulp vitality test [16], staining [17], transillumination [18], and computed tomography (CT) [19] were the most common clinical diagnosis methods. Surface crack detection methods such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) have recently attracted a lot of attention [20,21][20][21]. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and Micro-CT appeared to be more efficacious than traditional clinical dental imaging techniques in detecting longitudinal tooth cracks [22,23][22][23].

2. Clinical Features

The clinical symptoms differ according to the location and extension of the incomplete fracture [12,24,25][12][24][25]. It is possible to elicit a history of months of discomfort and acute pain while chewing or consuming cold beverages. “Rebound pain” or pain that occurs when pressure is released after eating fibrous foods is frequently observed. Patients may not be able to identify the tooth where the pain is felt. They may report a negative response to heat stimuli. Microleakage of bacterial byproducts and toxins can cause chronic pulpitis without causing clinical symptoms. Pulpal and periodontal symptoms may develop from cracks with pulpal involvement [26,27][26][27]. The physiological basis of chewing pain as proposed by Brannstrom and Astrom [28] states that the independent movement of the fractured tooth part with each other could cause a sudden transition in the fluids within the dentinal tubules. Subsequently, the A-type fibers get activated in the dental pulp leading to immediate pain. The toxic irritants may leak via the cracks producing hypersensitivity to cold. The release of neuropeptides as a result of the toxic irritant leakage within the dental pulp leads to a decreased pain threshold. These symptoms occur because of alternate compression and stretching of the odontoblast processes inside the crack. Asymptomatic enamel cracks can have multiple pathogenic consequences. Teeth with enamel cracks may be further damaged by ultrasonic instrumentation such as scaling and root planing [29].3. Difference between a Fractured Cusp or a Split Tooth and a Cracked Tooth

A cracked tooth can be differentiated from a split tooth by checking the movements of the segment by wedging. A cracked tooth demonstrates no movement with wedging pressures. Under light pressure, a split tooth may break off, leaving patients with no further mobility. Under wedging stresses, a fractured cusp will display mobility and the mobile part will extend deep beyond the cementoenamel junction. Postoperative sensitivity as a result of broken restoration, areas of hyper occlusion due to dental restoration, microleakage from newly filled composite resin restorations, orofacial pain, and bruxism pain, can all be considered as a cracked tooth [30].4. Causes of Enamel Cracks and Identification

The sources and causes of enamel cracks are multifactorial. They can develop glacially over a long time period. Enamel cracks can exist independent of dentin cracks. The pain from a cracked tooth can be difficult to distinguish from other conditions such as ear pain, atypical orofacial pain, migraine, sinusitis, or temporomandibular joint disorders. As a consequence, diagnosis may be clinically challenging and delayed. Early detection is critical because restorative treatment can prevent fracture propagation, microleakage, pulpal or periodontal tissue involvement, and catastrophic cusp failure [31]. The ease at which a fracture can be diagnosed varies depending on its location and extent. An extensive intracoronal repair is usually present on the tooth. Humans uniquely consume both hot and cold food, leading to repeated thermal changes that can cause expansion and contraction [32]. This is particularly relevant in the case of teeth restored with ceramics where thermal expansion and cyclic loading can lead to crack formation and propagation. Microscopic cracks at the edges of a restoration can indicate structural weakness [18]. Cracks at the margins of composite restorations may be due to polymerization contraction stress. It can present as a whitish margin [33]. Well-defined discoloration of a cusp can be a sign of a lack of structural integrity [18]. Pain can arise after dental procedures, such as the cementation of an inlay, and is often misdiagnosed to be due to the high spots on the recent restoration. The presence of underlying cracks could be indicated by regularly debonding the cemented intracoronal restorations like inlays.5. Classification/Definitions of Tooth Fracture

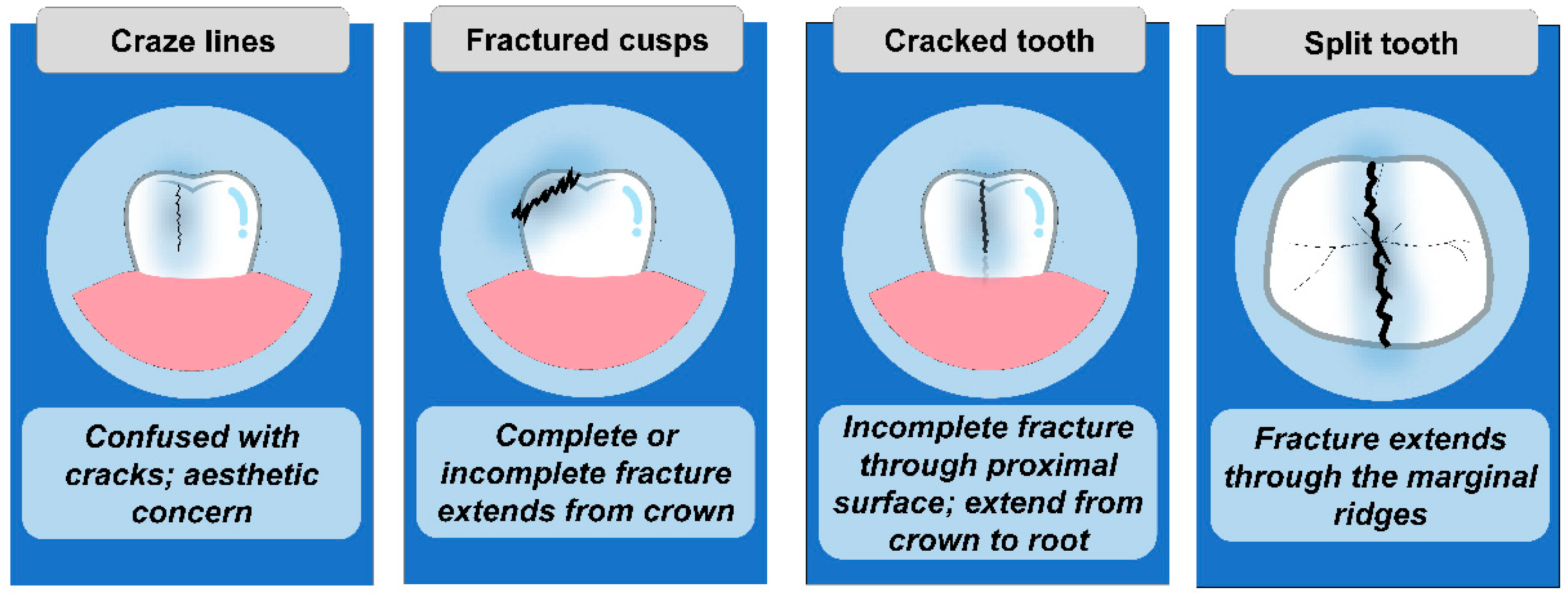

The American Association of Endodontists has divided longitudinal tooth fractures into five classes: craze line, fractured cusp, cracked tooth, split tooth, and vertical root fracture [34]. An asymptomatic crack in the tooth enamel may progress along with dentin cracks. Clinically distinguishing between the various types of cracks can be difficult (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Type of tooth fractures.

-

Craze Lines: Tiny and harmless cracks that occur in the outer enamel of the tooth.

-

Cracks: It occurs when craze lines penetrate the body of the tooth (dentin).

-

Fractures: A fracture occurs when cracks expand deep into the root of the tooth.

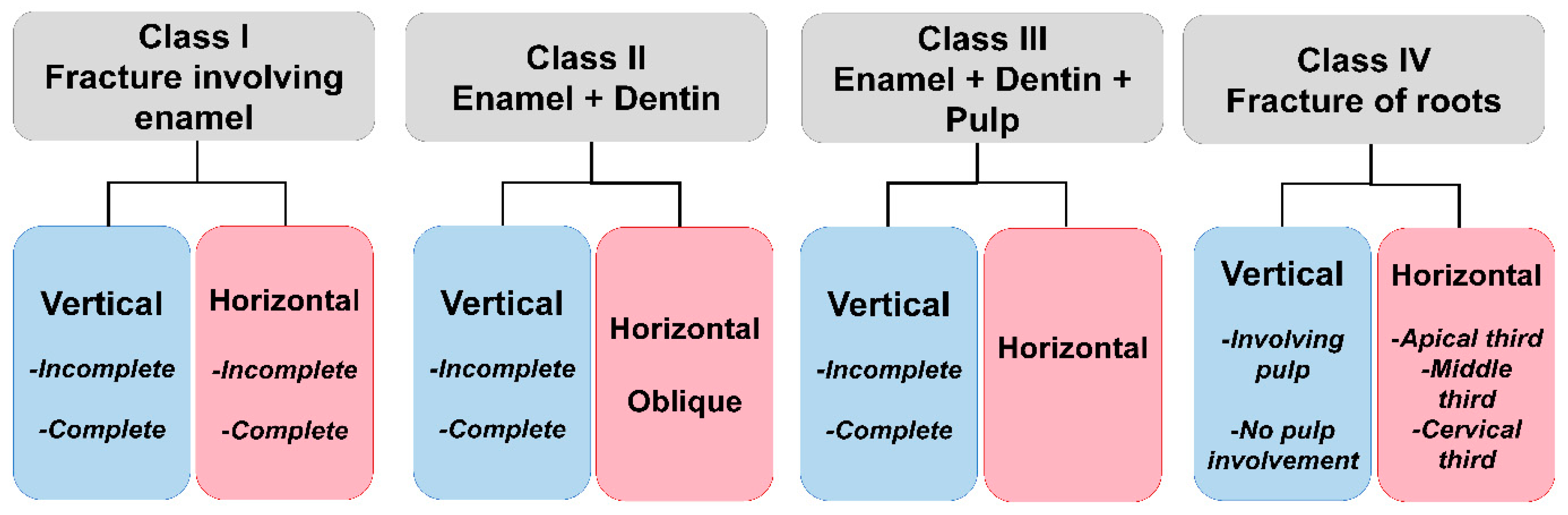

Figure 2.

6. Early Methods of Diagnosing Enamel Crack

6.1. Clinical Examination

Careful clinical examination can visualize localized periodontal defects (subgingival cracks), facets on the occlusal surface of the tooth, and positive response to thermal or sweet stimuli. Once the tooth has been located, many authors recommend removing old restorations and stains to view the cracks. Rubber dam usage has the advantage of detecting the cracks more easily by keeping the tooth surface free of saliva, highlighting the crack with a clear background and preventing the interference of surrounding structures.

6.2. Visual Inspection

Visual inspection is inherently limited. Traditional visualization may not be sensitive enough to assess the presence or severity of the cracks. Although visual examination of the tooth is beneficial, cracks cannot be visualized without magnifying loupes. While it can be identified, it is not always obvious. Once the tooth has been located, many authors recommend removing old restorations and stains to aid in the visualization of the crack [37,38,39,40,41][37][38][39][40][41].

6.3. Exploratory Excavation

It is often difficult to find the crack beneath the removed restoration, therefore the tooth should be further excavated with the consent of the patient.

6.4. Percussion Test

The cracked tooth could be diagnosed with a positive response to apical percussion.

6.5. Periodontal Probing

The cracked tooth can be differentiated from the split tooth using periodontal probing when the line of fracture progresses beyond the gingiva. Careful probing of suspected cracks is required to reveal a periodontal pocket. Deep probing, conversely, frequently helps in the diagnosis of a split tooth, which indicates a poor prognosis.

6.6. Dye Test

Fracture lines can be highlighted with methylene blue or gentian violet stains [42]. This is due to the dye’s tendency for aggregation. However, using the dye may hide cracks or cause slight color changes in the enamel’s deeper layers [18]. In addition, the original restorative elements must be excavated before dye application, which takes 2–5 days [43]. Another problem is that a permanent aesthetic restoration is not feasible.

6.7. Transillumination

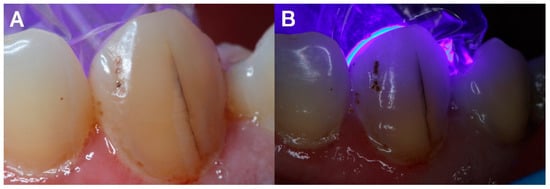

Transillumination is a useful tool for locating tooth cracks [44]. The tooth must be cleansed before transillumination, and the light source must be held above the tooth. The presence of any crack penetrating the tooth dentin will derange the transmission of light [45]. For traditional crack diagnosis, transillumination is the frequent method used (Figure 3). The use of transillumination without magnification has two disadvantages. Transillumination, for starters, causes the craze lines to give the impression of physical fractures. Additionally, the minor color shift is undetectable. The use of magnification and fiber-optic transillumination will aid in the visualization of a crack. The detected cracks, do not precisely signify the extent and form of the cracks [46].

Figure 3.

(

A

) Enamel crack. (

B

) Transillumination used to confirm presence of crack.

The intensification to determine its spectrum averages from 14–18×. As per experienced clinicians, 16 times seems to be the ideal magnification [47]. The minor cracks can be properly detected using the fiber-optic transillumination equipment and the dental microscope. These are widely used as effective diagnostic tools in clinical practice.

Transillumination combined with methylene blue allows better discrimination of enamel cracks than either modality alone [40].

References

- Türp, J.C.; Gobetti, J.P. The Cracked Tooth Syndrome: An Elusive Diagnosis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1996, 127, 1502–1507.

- Rosen, H. Cracked Tooth Syndrome. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1982, 47, 36–43.

- Ricucci, D.; Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Loghin, S.; Berman, L.H. The Cracked Tooth: Histopathologic and Histobacteriologic Aspects. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 343–352.

- Hilton, T.J.; Funkhouser, E.; Ferracane, J.L.; Gordan, V.V.; Huff, K.D.; Barna, J.; Mungia, R.; Marker, T.; Gilbert, G.H.; National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Associations of Types of Pain with Crack-Level, Tooth-Level and Patient-Level Characteristics in Posterior Teeth with Visible Cracks: Findings from the National Dental Practice-Based research Network. J. Dent. 2018, 70, 67–73.

- Ellis, S.G.S.; Macfarlane, T.V.; McCord, J.F. Influence of Patient Age on the Nature of Tooth Fracture. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1999, 82, 226–230.

- Hasan, S.; Singh, K.; Salati, N. Cracked Tooth Syndrome: Overview of Literature. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2015, 5, 164.

- Hiatt, W.H. Incomplete Crown-root Fracture in Pulpal-periodontal Disease. J. Periodontol. 1973, 44, 369–379.

- Yahyazadehfar, M.; Zhang, D.; Arola, D. On the Importance of Aging to the Crack Growth Resistance of Human Enamel. Acta Biomater. 2016, 32, 264–274.

- He, B.; Huang, S.; Zhang, C.; Jing, J.; Hao, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, X. Mineral Densities and Elemental Content in Different Layers of Healthy Human Enamel with Varying Teeth Age. Arch. Oral Biol. 2011, 56, 997–1004.

- Attin, T.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Wegehaupt, F.; Wiegand, A. Influence of Study Design on the Impact of Bleaching Agents on Dental Enamel Microhardness: A review. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 143–157.

- Lopes, G.C.; Bonissoni, L.; Baratieri, L.N.; Vieira, L.C.C.; Monteiro, S., Jr. Effect of Bleaching Agents on the Hardness and Morphology of Enamel. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2002, 14, 24–30.

- Geurtsen, W. The Cracked-Tooth Syndrome: Clinical Features and Case Reports. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 1992, 12, 395–405.

- Banerji, S.; Mehta, S.B.; Millar, B.J. Cracked Tooth Syndrome. Part 1: Aetiology and Diagnosis. Br. Dent. J. 2010, 208, 459–463.

- Yang, S.-E.; Jo, A.-R.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, S.-Y. Analysis of the Characteristics of Cracked Teeth and Evaluation of Pulp Status According to Periodontal Probing Depth. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 135.

- Kim, J.-H.; Eo, S.-H.; Shrestha, R.; Ihm, J.-J.; Seo, D.-G. Association between Longitudinal Tooth Fractures and Visual Detection Methods in Diagnosis. J. Dent. 2020, 101, 103466.

- Gopikrishna, V.; Pradeep, G.; Venkateshbabu, N. Assessment of Pulp Vitality: A Review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2009, 19, 3–15.

- Ghorbanzadeh, A.; Aminifar, S.; Shadan, L.; Ghanati, H. Evaluation of Three Methods in the Diagnosis of Dentin Cracks Caused by Apical Resection. J. Dent. 2013, 10, 175.

- Clark, D.J.; Sheets, C.G.; Paquette, J.M. Definitive Diagnosis of Early Enamel and Dentinal Cracks Based on Microscopic Evaluation. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2003, 15, 391–401.

- Landrigan, M.D.; Flatley, J.C.; Turnbull, T.L.; Kruzic, J.J.; Ferracane, J.L.; Hilton, T.J.; Roeder, R.K. Detection of Dentinal Cracks Using Contrast-Enhanced Micro-Computed Tomography. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2010, 3, 223–227.

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.-J.; Chung, H.-J.; Park, J.-T.; Kim, H.-J. Dental Optical Coherence Tomography: New Potential Diagnostic System for Cracked-Tooth Syndrome. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2016, 38, 49–54.

- Kim, J.-M.; Kang, S.-R.; Yi, W.-J. Automatic Detection of Tooth Cracks in Optical Coherence Tomography Images. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2017, 47, 41–50.

- Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, L.; Qiao, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Wu, L. The Extent of the Crack on Artificial Simulation Models with CBCT and Periapical Radiography. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169150.

- Leader, D.M. CBCT Is Valuable for Diagnosis of Tooth Fracture. Evid. Based Dent. 2015, 16, 23–24.

- Chong, B.S. Bilateral Cracked Teeth: A Case Report. Int. Endod. J. 1989, 22, 193–196.

- Ehrmann, E.H.; Tyas, M.J. Cracked Tooth Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment and Correlation between Symptoms and Post-Extraction Findings. Aust. Dent. J. 1990, 35, 105–112.

- Brannstrom, M. Dentin and Pulp in Restorative Dentistry; Dental Therapeutic AB: Nacka, Sweden, 1981; Volume 70.

- Bergenholtz, G. Pathogenic Mechanisms in Pulpal Disease. J. Endod. 1990, 16, 98–101.

- Brannstrom, M. The Hydrodynamics of the Dentine. Its Possible Relationship to Dentinal Pain. Int. Dent. J. 1972, 22, 219–227.

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kang, M.-K.; Kang, S.-M.; Kim, H.-E. Effects of Ultrasonic Instrumentation on Enamel Surfaces with Various Defects. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, 219–224.

- Mathew, S.; Thangavel, B.; Mathew, C.A.; Kailasam, S.; Kumaravadivel, K.; Das, A. Diagnosis of Cracked Tooth Syndrome. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012, 4, S242.

- Kahler, W. The cracked tooth conundrum: Terminology, Classification, Diagnosis, and Management. Am. J. Dent. 2008, 21, 275.

- Çelik Köycü, B.; İmirzalıoğlu, P. Heat Transfer and Thermal Stress Analysis of a Mandibular Molar Tooth Restored by Different Indirect Restorations Using a Three-Dimensional Finite Element Method. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 460–473.

- Fusayama, T. Indications for Self-Cured and Light-Cured Adhesive Composite Resins. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1992, 67, 46–51.

- Rivera, E.M.; Walton, R.E. Cracking the Cracked Tooth Code: Detection and Treatment of Various Longitudinal Tooth Fractures. Am. Assoc. Endodontists Colleagues Excell. News Lett. 2008, 2, 1–19.

- Silvestri, A.R., Jr.; Singh, I. Treatment Rationale of Fractured Posterior Teeth. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1978, 97, 806–810.

- Talim, S.T.; Gohil, K.S. Management of Coronal Fractures of Permanent Posterior Teeth. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1974, 31, 172–178.

- Davis, R.; Overton, J.D. Efficacy of Bonded and Nonbonded Amalgam in the Treatment: Of Teeth with Incomplete Fractures. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 131, 469–478.

- Luehke, R.G. Vertical Crown-Root Fractures in Posterior Teeth. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1984, 28, 883–894.

- Ailor, J.E., Jr. Managing Incomplete Tooth Fractures. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2000, 131, 1168–1174.

- Wright, H.M., Jr.; Loushine, R.J.; Weller, R.N.; Kimbrough, W.F.; Waller, J.; Pashley, D.H. Identification of Resected Root-End Dentinal cracks: A Comparative Study of Transillumination and Dyes. J. Endod. 2004, 30, 712–715.

- Cooley, R.L.; Barkmeier, W.W. Diagnosis of the Incomplete Tooth Fracture. Gen. Dent. 1979, 27, 58–60.

- Liu, H.H.; Sidhu, S.K. Cracked Teeth—Treatment Rationale and Case Management. Quintessence Int. 1995, 26, 485–492.

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Qi, Y.; Ma, X.; Qiao, S.; Cai, H.; Zhao, B.C.; Jiang, H.B.; Lee, E.-S. Comparison of Autogenous Tooth Materials and Other Bone Grafts. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 327–341.

- Liewehr, F.R. An Inexpensive Device for Transillumination. J. Endod. 2001, 27, 130–131.

- Pitts, D.L.; Natkin, E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vertical Root Fractures. J. Endod. 1983, 9, 338–346.

- Mamoun, J.S.; Napoletano, D. Cracked Tooth Diagnosis and Treatment: An Alternative Paradigm. Eur. J. Dent. 2015, 9, 293–303.

- Madrid, C.C.; de Pauli Paglioni, M.; Line, S.R.; Vasconcelos, K.G.; Brandão, T.B.; Lopes, M.A.; Santos-Silva, A.R.; De Goes, M.F. Structural Analysis of Enamel in Teeth from Head-and-Neck Cancer Patients Who Underwent Radiotherapy. Caries Res. 2017, 51, 119–128.

More