Atypical atrial flutters (AAFL) are difficult-to-manage atrial arrhythmias, yet potentially amenable to effective radiofrequency catheter ablation (CA). However, data on CA feasibility are only sparingly reported in the literature in different clinical settings, such as AAFL related to surgical correction of congenital heart disease. The aim of this review was to provide an overview of the clinical settings in which AAFL may occur to help the cardiac electrophysiologist in the prediction of the tachycardia circuit location before CA. Moreover, the role and proper implementation of cutting-edge technologies in this setting were investigated as well as which procedural and clinical factors are associated with long-term failure to maintain sinus rhythm (SR) to find out which patients may, or may not, benefit from this procedure. Not only different surgical and non-surgical scenarios are associated with peculiar anatomical location of AAFL, but we also found that CA of AAFL is generally feasible. The success rate may be as low as 50% in surgically corrected congenital heart disease (CHD) patients but up to about 90% on average after pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) or in patients without structural heart disease. Over the years, the progressive implementation of three-dimensional mapping systems and high-density mapping tools has also proved helpful for ablation of these macro-reentrant circuits. However, the long-term maintenance of SR may still be suboptimal due to the progressive electroanatomic atrial remodeling occurring after cardiac surgery or other interventional procedures, thus limiting the likelihood of successful ablation in specific clinical settings.

- atypical atrial flutter

- atrial fibrillation

- catheter ablation

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Settings Associated with Atypical Atrial Flutters

2.1. Surgical Correction for Congenital Heart Disease

Macro-rentrant atrial arrhythmias or post-incisional IART represent common complications after surgical correction for congenital heart disease [8]. IART generally develops in adulthood several years after surgery and is often poorly tolerated in these patients [2]. Cavo-tricuspid isthmus-dependent AFL is seen in at least 58% of patients after cardiac surgery [2][9][2,9], whereas IART occurs in up to 25% of cases [2]. On the one hand, anatomical position of surgical scars deeply influences IART location. In patients with a history of atrial septal defect (ASD) and Tetralogy of Fallot repair, the observed macro-rentrant circuits revolving around areas of dense scar or through electrical gaps along double potential lines are generally consistent with the right-sided location of surgical atriotomies [2]. Re-entry around septal patch and left-sided IART have been also observed in rarer cases after ASD correction [2][10][2,10]. The electrophysiology substrate is even more complex when Fontan procedure for univentricular hearts is considered [11]. Due to the major hemodynamic abnormalities in these patients, the anatomical location of IART is difficult to predict and depends on the combination of iatrogenic areas of conduction block in heavily remodeled right atrial chambers [11]. However, the classic Fontan (i.e., right atrial to pulmonary artery anastomosis) and the intracardial lateral tunnel were more recently replaced by the so-called extracardiac Fontan where completely external conduits are used. Thanks to a total cavopulmonary connection created through right atrial bypass, the extracardiac Fontan operation has progressively led to a significant reduction in IART occurrence in these patients [12]. In this complex scenario, the implementation of three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping systems proved invaluable in the better understanding of the pathophysiological substrates of these cardiac arrhythmias [11]. F2.2. Cardiac Surgery for Acquired Heart Disease

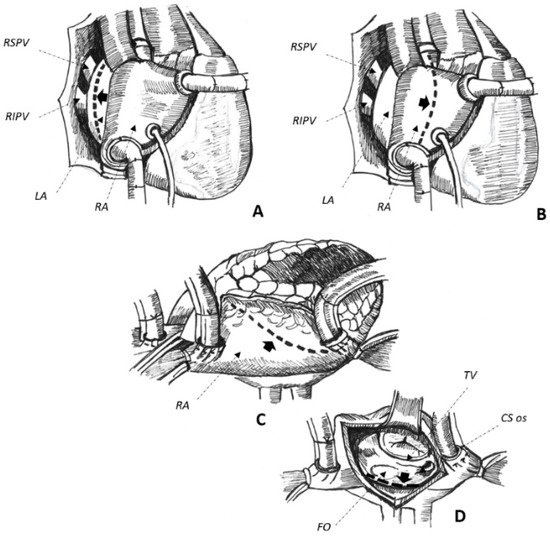

Cardiac surgery for the correction of mitral valve (MV) disease is common and associated with the development of complex, macro-reentrant arrhythmias revolving around iatrogenic scars [13][14][13,14]. In this setting, AAFL is observed in up to 55% of cases [3] and their anatomical location is greatly influenced by atriotomies and cannulation sites performed at the time of surgery [13]. Three major atriotomies have been described for surgical correction of MV disease, as follows: (1) left atrial atriotomy as an incision between the right pulmonary veins and the interatrial septum (Waterston’s groove) (Figure 1A); (2) Guiraudon’s approach or superior trans-septal access involving a vertical right atriotomy extended over the superior right atrium, the septum, and the dome of the left atrium (Figure 1B); and, finally, (3) combined trans-septal approach consistent of a vertical right atriotomy parallel to the atrio-ventricular sulcus (Figure 1C) followed by a separate incision in the interatrial septum (Figure 1D) [15].

2.3. Non-Surgical Pulmonary Vein Isolation

2.4. Absence of Manifest Structural Heart Disease

In up to 6% of cases, AAFL occurs in patients with no evidence of structural heart disease [5]. Reasons for spontaneous atrial scarring are not clear. However, chronically increased atrial pressure overload in hypertension, occlusion of small coronary artery branches, isolated inflammation, and finally amyloid infiltration may explain an arrhythmogenic substrate in otherwise apparently healthy individuals [5][27][5,30]. Most of these circuits are right-sided and usually involve electrical silent areas located at the posterior or the lateral free wall of the right atrium, which can be effectively treated by radiofrequency energy applications delivered from these scars to the inferior vena cava ostium [5][28][5,31]. However, narrow and slow-conducting channels may also be found in left-sided, antero-septal circuits, as the result of the complex interweaving of epicardial fibers promoting AAFL [5]. Finally, even in normal hearts, transverse conduction across the crista terminalis [27][30] and the complex anatomy of the interatrial septum [29][32] may lead to macro-reentrant arrhythmias due to mechanisms of non-uniform anisotropy [27][30][30,33].3. Overall Peri-Procedure Feasibility

Although pioneering works based their CA strategy on conventional mapping through the systematic evaluation of transient concealed entrainment and post-pacing intervals at different pacing sites [10][31][32][10,34,35], the feasibility of entrainment is known to be limited due to pacing-mediated arrhythmia termination, degeneration into AF, or increased pacing thresholds in patients on antiarrhythmic medications [28][33][34][35][31,36,44,46]. Moreover, AAFL are complex arrhythmogenic circuits sustained by double or multiple loops in up to 60% of cases, which would make an ablation strategy based on conventional mapping particularly challenging [10]. To overcome these issues, three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping systems have been progressively implemented in cardiac electrophysiology to guide mapping [33][35][36][36,46,58] and to achieve effective radiofrequency ablation of these complex circuits [7][9][34][35][37][38][39][7,9,44,46,49,55,57]. In fact, when these systems are used, the peri-procedure success rate spans from 65% [40][37] to 100% [9][37][39][41][9,49,53,57], with better results observed in patients with a history of non-surgical PVI or in case of no structural heart disease [36][41][42][48,53,58]. However, despite the implementation of the latest technologic developments in experienced hands, such as high-density mapping tools [43][44][54,56] or contact-force sensing catheters [44][56], peri-procedure failure is observed in up to 15–20% of cases [43][44][54,56], with a greater chance of acute failure in patients with history of surgical correction for CHD [40][37]. Difficult-to-ablate anatomical substrates [10], peculiar features of the targeted isthmi [45][46][51,52], and their anatomical locations [35][47][46,59], may explain failures. Further, a CA procedure may also be prematurely interrupted for safety issues to avoid right hemidiaphragm palsy [32][35], inadvertent block of the atrioventricular node [35][46], or atrial wall perforation with possible cardiac tamponade. Finally, the inherent complexity of CA of AAFL is proved by the reported long procedure [48][39] and fluoroscopy times [33][36]. As for the overall peri-procedure safety, local complications may occur in up to 7% of cases, including groin hematoma (up to 7%) [48][39], arteriovenous fistula (3–4%) [35][45][46,51], and femoral pseudoaneurysm (1.4%) [31][34] in generally anticoagulated patients. On the other hand, regarding systemic complications, cerebral [4][33][4,36] and peripheral [32][35] embolism could be as high as 4–6% with potentially life-threatening major bleedings only sparingly described, including retroperitoneal hemorrhage (2.2%) reported in one study only [3]. Finally, patients with mechanical valve prostheses may portend even a greater risk of peri-procedure thromboembolic or hemorrhagic complications. Therefore, particular attention should be paid to periprocedural antithrombotic regimens in this patient population to avoid potentially life-threatening events [14].4. Maintenance of Sinus Rhythm after a Successful Procedure

As displayed in Table 1, AAFL recurrence is observed in up to 62% of cases after a single CA procedure with an overall SR maintenance as low as 38% on/off AAD after a variable follow-up duration, spanning from 7 ± 3 [43][54] to 37 ± 15 [5] months. Data on whether patients were on AAD before the procedure and at follow-up was not available in most of the studies, and the effect of AAD is therefore unclear in this setting.

The older the publication date, the greater the incidence of arrhythmia recurrence. This would suggest that the recent implementation of dedicated mapping tools [39][57] and irrigated-tip catheters [37][49][42,49] could help the cardiac electrophysiologist to achieve a greater long-term SR maintenance after an initially successful CA procedure [39][45][51,57]. The adoption of dedicated, tachycardia-oriented strategies for mapping and ablation of AAFL seem associated with even better results [35][45][46,51]. However, the greater the complexity of the atrial substrate to ablate, the higher the incidence of arrhythmia recurrence at follow-up. The worst long-term clinical outcome is commonly seen in patients with surgically corrected CHD (46–52% AAFL recurrence) [31][32][34,35], with better results observed after PVI (16–28%) [19][36][21,58] or in patients with apparently normal hearts (9–25% of tachycardia recurrence) [5][28][5,31].