3.1.1. TLS Polymerases Structural Features

TLS polymerases belong to the B-family (Polζ) and the Y-family (Polη, Polι, Polκ and Rev1) of DNA polymerases

[93][128]. Despite being highly conserved throughout evolution

[94][129], the TLS pathway displays substantial variability in polymerase distribution among species. Thus, only Polζ, Polη and Rev1 are present in budding yeast.

-Polζ comprises the Rev3 catalytic subunit and Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32 accessory subunits. Former in vitro studies determined that Rev3 physically interacts by its N-terminal region with Rev7, with both being subunits required for a minimally functional complex

[95][130]. Later, it was shown that Pol31 and Pol32, which are both subunits of Polδ, were purified along with Rev3-Rev7 to form a fully functional complex

[96][97][98][99][131,132,133,134]. The recently resolved structure of Polζ reveals the presence of a pentameric ring conformation that contains two Rev7 subunits, in addition to Rev3, Pol31 and Pol32

[100][135].

-Polη is thought to be a first responder in TLS, being rapidly recruited to stalled RFs. It was first identified in yeast due to its ability to replicate UV light-induced DNA lesions such as cis-syn thymine-thymine (TT) and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD), in an error-free manner

[101][102][143,144]. In humans, Polη was first identified as the mutated product of the

XPV gene in patients with the xeroderma pigmentosum-variant

[103][145].

-Rev1 contains a polymerase domain, a polymerase-associated domain (PAD) that is the active site that coordinates the essential metallic ions required for the nucleotidyl transferase reaction, and two IDRs, whereby the N-terminal IDR encloses a BRCT (breast cancer-associated protein-1 C-terminal) domain that binds on the front of PCNA at a site that partially overlaps with the PIP motif-binding site

[104][105][151,152], while the C-terminal IDR contains two small ubiquitin-binding motifs (UBM)

[106][153], and a small CTD

[72][107][108][72,154,155]. This four-helix bundle binds to a region of the catalytic core of Polζ

[109][110][156,157].

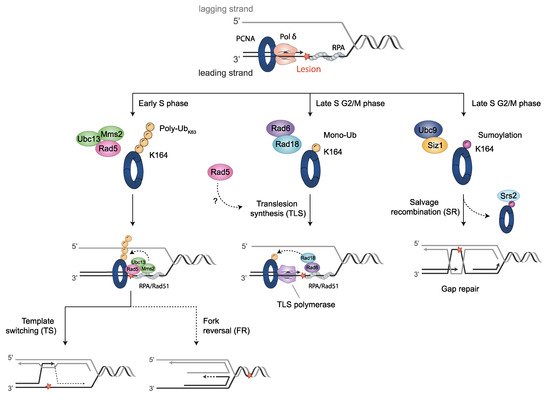

3.1.2. Monoubiquitin-PCNA Modification Mediated by Rad6-Rad18

The activation of TLS involves post-translational modifications of the sliding clamp PCNA, consisting of monoubiquitination at highly conserved lysine K164 by the Rad6 E2 ubiquitin conjugase and the Rad18 E3 ubiquitin ligase. Although PCNA monoubiquitination is an essential step in TLS, its specific role is still not known in detail. However, it has been assumed that ubiquitin-modified PCNA is a signal to recruit TLS polymerases to stalled RFs

[89][106][111][112][113][114][124,153,163,164,165,166]. Accordingly, an increased activity of both Rev1 and Polη is observed when binding ubiquitin-modified PCNA, compared with unmodified PCNA

[114][166].

3.1.3. DNA Polymerase Switching during TLS

The term polymerase switching refers to the process by which one DNA polymerase replaces a second one at the 3′-OH end of a primed DNA template. Two model strategies to switch replicative polymerases for TLS have been described. A first model is termed the PCNA “tool belt”, in which multiple binding proteins may be recruited to PCNA monomers that are not bound by Polδ. Thus, the ubiquitin moiety is located on the backside of PCNA, where TLS polymerases may be engaged, while Polδ remains bound at the front

[115][184]. This model is supported by a recent work of the human Polδ-PCNA-FEN1 complex on DNA

[73], suggesting this mechanism for flap cleavage in Okazaki fragment maturation. Lancey et al.

[73] showed the ability of PCNA to adopt a 20° tilted position, leading to the destruction of the critical interactions for DNA synthesis between the catalytic subunit of Polδ and PCNA, while the polymerase remains bound to PCNA via the PIP box. Other pieces of evidence for the “tool belt” model of polymerase switching have been reported in other organisms such as

Escherichia coli [116][117][185,186] and archaea

[118][187].

The second proposed mechanism comprises the formation of Rev1 bridges, in which a TLS polymerase is linked to PCNA via Rev1, without directly interacting with the clamp. In this model, Polδ dissociates from PCNA and DNA to permit TLS. Rev1 interacts with PCNA through the BRCT domain, and through PIP-like motifs with other Y-family polymerases

[78] or with the Rev7 subunit of Polζ

[119][120][116,188]. Accordingly, numerous studies support a non-catalytic role of Rev1 in the recruitment of other TLS polymerases

[121][122][123][124][189,190,191,192]. Single-molecule studies revealed that both mechanisms, “tool belt” and Rev1 bridges, are able to dynamically interchange without dissociation

[119][125][116,147].

Defective-Replisome-Induced-Mutagenesis (DRIM) occurs when problems in replication factors, affecting replisome integrity or Polα, Polδ or Polε, promote the use of Polζ to continue DNA synthesis copying undamaged DNA. As a consequence, the low fidelity of Polζ causes an increase in the mutational rate

[126][127][128][129][195,196,197,198].

3.2. Rad5-Mediated Error-Free DDT Bypass Pathway

3.2.1. Polyubiquitinated PCNA by Rad5- Error-Free Pathway

Monoubiquitinated PCNA may be modified by the heterodimeric E2 ubiquitin conjugase enzymes Ubc13-Mms2 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Rad5, in

S. cerevisiae, (or the Rad5 orthologous SHPRH and HLTF in humans). This modification involves K63-polyubiquitin chain extension onto K164 of PCNA. Genetic studies support this notion, since

RAD5,

UBC13 or

MMS2 mutant cells are impaired in PCNA polyubiquitin chain formation, without affecting its monoubiquitination in vivo

[111][163]. Polyubiquitinated-PCNA presumably signals error-free DDT pathway activation, mostly mediated by transient template switching, TS, in which the stalled nascent DNA strand uses the newly synthesized, undamaged strand of the sister chromatid as a template for replication

[130][131][204,205] (see Section 3.2.3). Accordingly, mutants in this error-free pathway exhibit higher sensitivity to DNA damaging agents than mutants in the TLS pathway

[132][133][206,207]. Polyubiquitin chain studies reveal that, rather than the total number of ubiquitin moieties, chain geometry is critical for error-free DDT bypass, suggesting that a still unknown receptor, with high selectivity for UBD, mediates TS activation

[134][208]. Further work is required to uncover the complexity of ubiquitin as a signalling factor, the mechanisms by which polyubiquitinated-PCNA activates TS, and the effectors that are involved.

3.2.2. Structural Features of Rad5, Interactions and Associated Activities

Rad5 has structured domains separated by IDRs. These domains include HIP116, Rad5p, the N-terminal (HIRAN) domain, helicase domain, and a RING domain, which is strikingly embedded into the helicase domain

(Figure 3e). The HIRAN domain of Rad5 contains an oligonucleotide-binding fold (OB) that specifically binds the 3′ end of ssDNA, but prevents the binding of dsDNA binding

[135][136][137][138][209,210,211,212].

Rad5 belongs to the SF2 superfamily of helicases

[139][213]. Its helicase domain encompasses the half C-terminus of Rad5, and harbors seven conserved motifs, including Walker A and Walker B ATP-binding motifs. Furthermore, the helicase domain also binds DNA. The DNA-dependent ATPase activity of Rad5 becomes stimulated by either ssDNA or dsDNA. The yeast Rad5 DNA helicase activity is specialized in RF regression

[138][212] (see

Section 3.2.4). The Rad5 RING consists of a C3HC4 zinc finger-type domain formed by seven cysteine residues and one histidine residue coordinating two zinc ions

[138][212]. It binds to Ubc13-Mms2 and is involved in Rad5 ubiquitin ligase activity

[140][214]. Ubiquitin ligase and ATPase activities are essential for a functional error-free DDT pathway. Hence, mutations in any of the associated domains show sensitivity to DNA damage and increased mutagenesis, similar to

∆mms2 or

∆ubc13 mutant cells

[141][215].

3.2.3. Template Switch (TS) Model

The TS model for the error-free mechanism of DDT requires a process of strand invasion, which progresses in an HR-dependent manner

[142][175]. Hence, some components playing a role in the HR also participate in the TS pathway. Frequently, specific HR intermediate structures are generated during the process. In summary, the TS begins with a strand invasion, in which the undamaged sister chromatid is transiently used as a replication template, exchanging the template for the blocked nascent strand, in order to carry over replication. This step is likely mediated by Rad51, and once the region containing the DNA lesion in the parental strand is replicated, the nascent strand switches back again to its original proper strand, leading to the restart of normal replication. Consequently, the appearance of derivative intermediates as X-shaped DNA or Rec-X structures (also called “sister chromatid junctions”, SCJ) occurs with some frequency throughout the process.

3.2.4. Fork Reversal Model

Fork reversal or fork regression is a regulated process used to stabilize stalled RFs and promote error-free lesion bypass, preventing ssDNA extension. This process requires the action of helicases and DNA translocases

[143][144](reviewed in [229,230]). To overcome or facilitate the repair of a lesion that stalls the fork, nascent daughter strands dissociate from parental strands and anneal with each other, while the fork regresses and parental strands are reannealed, generating a four-way junction structure named “chicken foot”

[145][231], where free ends on the reversed daughter strands must be protected from degradation. Fork reversal may imply TS, when the regressed lagging strand is used as the template to copy the leading strand.

3.3. Alternative Ubiquitination Sites in PCNA

Alternative ubiquitination sites have been identified in

S. cerevisiae [146](reviewed in [252]). K107 is specifically ubiquitinated in response to deficient DNA ligase I activity and to the accumulation of unligated Okazaki fragments

[147][148][253,254]. This modification has been proposed as a DNA nick sensor. The ubiquitination of this alternative site is required to initiate the S phase checkpoint and promote a cell cycle delay when the maturation of Okazaki fragments is impaired. It depends on Rad5 (or Rad8 in fission yeast), together with the E2 partner formed by Mms2 and Ubc4, but not by Ubc13

[147][149][253,255]. K107 in yeast PCNA is positioned at the interface between PCNA subunits

[149][255], suggesting that ubiquitination at this site might change the PCNA structure and the interaction between subunits, which would impair the correct function of PCNA. Related to this, in fission yeast, K107 ubiquitination was proposed to contribute to increased non-allelic crossovers, leading to gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs) depending on Rad52

[149][255].

3.4. PCNA Sumoylation: Regulation of Homologous Recombination (HR)

3.4.1. Srs2 Helicase Negatively Regulates the HR Pathway

Yeast PCNA is also conjugated with SUMO. Its significance, however, is less understood than ubiquitination. It is mostly accepted that the SUMO-modified PCNA leads to the suppression of HR through the recruitment of the Srs2 helicase

[150][257], which removes Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments from ssDNA

[151][258], and is critical to antagonize HR and to remove unproductive recombination intermediates

[152][259]. The

SRS2 gene was originally identified in screens for suppressors of yeast

∆rad6 sensitivities to trimethoprim and UV

[153][260]. The Srs2 function prevents HR, since suppressions mediated by an

∆srs2 mutant require functional components of the HR

[154][261].

Srs2 activity involved in disrupting Rad51 nucleofilaments was termed “strippase” activity, which differs from the helicase function, although both entail the Srs2 translocase activity. Srs2 interacts with both Rad51 and SUMO-modified PCNA to complete its anti-recombination role during DNA replication. While the helicase domain is located at its N-terminus, Srs2 presents a flexible C-terminal region responsible for different protein interactions

[155][262]. Accordingly, a conserved SIM and a degenerated PCNA interaction motif (PIM-like) are present at the very end of the C-terminus

[115][156][184,263].

3.4.2. PCNA Sumoylation by Ubc9-Siz1

SUMO attachment to PCNA occurs primarily at the same K164 residue involved in monoubiquitination, and it is mediated by the E2 SUMO conjugase Ubc9 and the E3 SUMO ligase Siz1. To a minor extent, sumoylation at K127 has also been reported, in which only Ubc9 is required. K164 SUMO-modified PCNA occurs constitutively during the S phase in

S. cerevisiae, but it is not related to cell cycle checkpoints. Despite sharing K164 residues, the levels of both SUMO and ubiquitin modifications do not seem to antagonize each other, since in

∆rad18 mutants, which are unable to ubiquitinate PCNA, the SUMO-modified PCNA levels remain invariable

[111][163].

Ubc9 was isolated using SUMO affinity chromatography

[154][157][261,268]. Siz1 is a member of the Siz/PIAS RING family of SUMO E3 ligases. Structural studies of Siz1 revealed that it contains an N-terminal PINIT domain, a central zinc-containing RING-like, SP-RING domain, and a CTD, termed SP-CTD. Biochemical studies show that both the SP-RING and SP-CTD are required for the activation of the E2~SUMO thioester, while the PINIT domain is essential in interactions with the K164-PCNA

[141][215].

3.4.3. Salvage Recombination (SR) Pathway

The salvage pathway, or salvage recombination (SR), is an alternative mechanism to DDT

[158][271]. It is considered the last option, occurring at late S or G

2 phases, since recombination events during replication must be highly controlled to avoid the accumulation of toxic recombination intermediates and genomic instability.

In budding yeast, during replication, sumoylated PCNA recruits the Srs2 helicase, which inhibits unscheduled recombination at ongoing RFs by disrupting Rad51 filaments

[150][159][257,264]. The Srs2 anti-recombinogenic function is locally counteracted by Esc2 at stalled RFs

[160][272], to allow for the error-free bypass of DNA lesions depending on recombination. Esc2 contributes to this pathway with the following two different functions: (i) it facilitates Elg1 association to damaged forks, enhancing PCNA unloading, together with bound Srs2, therefore, it limits the quantity of Srs2 specifically at damaged forks. (ii) In addition, Esc2 interacts through its SUMO-like domain (SLD), with the SIMs of Srs2 and Slx5, a subunit of the Slx5/Slx8 SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL), causing local ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation of Srs2. As a consequence, a low presence of Srs2 facilitates the Rad5-dependent TS pathway at stalled forks.

3.5. PCNA Inner Surface Acetylation in Response to DNA Damage

The evolutionary highly conserved PCNA inner surface plays an important role for DNA polymerase processivity during replication and repair

[3]. However, the dynamic interaction between DNA and the positively-charged sliding surface is not well understood

[161][277]. Billon et al. showed that lysines on the inner surface of PCNA become acetylated in response to DNA damage, making cells more resistant to DNA-damaging agents. Specifically, K20 and K77 act as specific responders, since cell sensitivity to DNA damaging agents increases when they are replaced by acetyl-mimic glutamine residues. EcoI cohesin acetyltransferase acetylates K20 in vitro and in vivo in response to DNA damage, which stimulates repair by sister-chromatid-mediated HR. Moreover, the crystal structure of the PCNA ring acetylated on K20 reveals structural differences at the interface between PCNA subunits, which may suggest that transient conformational changes of the PCNA ring could have an effect on the sliding motion on the DNA. The effect of K77 acetylation has yet to be determined

[162][278].