The plasticity of the genome is an evolutionary factor in all animal species, including canines, but it can also be the origin of diseases caused by hereditary genetic mutation. Genetic changes, or mutations, that give rise to a pathology in most cases result from recessive alleles that are normally found with minority allelic frequency. The use of genetic improvement increases the consanguinity within canine breeds and, on many occasions, also increases the frequency of these recessive alleles, increasing the prevalence of these pathologies. This prevalence has been known for a long time, but mutations differ according to the canine breed. These genetic diseases, including skin diseases, or genodermatosis, which is narrowly defined as monogenic hereditary dermatosis. Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa constitutes a heterogeneous group of hereditary blistering diseases of the skin and mucous membranes.

The plasticity of the genome is an evolutionary factor in all animal species, including canines, but it can also be the origin of diseases caused by hereditary genetic mutation. Genetic changes, or mutations, that give rise to a pathology in most cases result from recessive alleles that are normally found with minority allelic frequency. The use of genetic improvement increases the consanguinity within canine breeds and, on many occasions, also increases the frequency of these recessive alleles, increasing the prevalence of these pathologies. This prevalence has been known for a long time, but mutations differ according to the canine breed. These genetic diseases, including skin diseases, or genodermatosis, which is narrowly defined as monogenic hereditary dermatosis.

1. Introduction

During recent centuries, genetic pathologies in canine breeds have increased considerably, possibly because of a reduction in the effective number of individuals in canine populations due to genetic selection. Such a focus on morphological characteristics has limited the number of alleles, thereby increased consanguinity, and reduced genetic diversity. This has mainly occurred due to inadequate crossing practices, together with insufficient selective pressure on canine well-being and health characteristics

[1]. In fact, the effective number of some canine breeds has been estimated at 30–70%, and inbred dogs after two generations have ranged from 1 to 8%, depending on mating practices

[2]. Genetic selection has focused on aesthetics rather than function or health, so a small number of breeders have been crossed with closed relatives, producing significantly reduced genetic diversity and increasing the prevalence of specific deleterious alleles

[3][4][5][3,4,5]. Dermatological pathologies are no exception, and some have increased considerably in certain breeds. For these, it is important to distinguish genodermatosis (dermatoses of a monogenic origin) from polygenic dermatoses with racial predisposition, the latter being more frequent than others

[6].

The high prevalence of genetic diseases in dog breeds and the structure of their populations has led to detailed studies of the canine genome, which are important for understanding the origin of these pathologies. For this reason, it was possible to determine that the canine genome has about 2.42 gigabases (Gb) composed of 20,000 genes distributed on 78 chromosomes, 38 pairs of acrocentric autosomes, and a pair of sex chromosomes: the X chromosome, the largest karyotype with 128 megabases (Mb), and the Y chromosome with the smallest karyotype of 27 Mb

[7]. Whole canine genome mapping, sequencing, and linkage analyses has made possible the highlighting of several disease-related sources. First, the high incidence of SINE (short interspersed nuclear element), which are repeated sequences associated with many diseases

[8]; the frequent occurrence of SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms), which are variations of a single nucleotide in the genome

[9], and the location of certain genes involved in several autosomal recessive monogenic diseases, including genodermatosis, have made it possible to reveal multiple causes of disease occurrence.

The canine genodermatosis are mainly non-epidermolytic ichthyosis in the Golden Retriever and the Jack Russell Terrier, epidermolytic ichthyosis in the Norfolk Terrier, junctional epidermolysis bullosa in the German Shorthaired Pointer, and Shar-Pei mucinosis, although other types of canine genodermatosis exist (Table 1).

Table 1. Genodermatosis with known causative genetic variants in dog breeds.

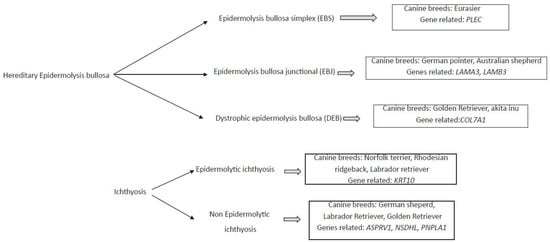

Different genodermatosis has been correlated to canine breed, and the several genes seems to be the responsible for these diseases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram of mainly monogenic hereditary skin disease, the associated canine breed, and the related genes.

2. Hereditary Epidermolysis Bullosa

Hereditary epidermolysis bullosa constitutes a heterogeneous group of hereditary blistering diseases of the skin and mucous membranes

[22][23][22,23]. These pathologies are characterized by the spontaneous development of vesicles, erosions, and ulcers because of minimal trauma to the excessively fragile dermal–epidermal junction (DEJ)

[24]. This group of dermal diseases is classified according to the level of cleavage as epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS), epidermolysis bullosa junctional (EBJ), and dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB). Different dog breeds have been associated with each of these diseases and have presented different types of ulcers. Some genes with recessive autosomal inheritance have been associated with them (

Table 2).

Table 2. Classification of canine epidermolysis, related ulcerations, and the associated genes and canine breeds.

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) is a skin disease, in which the keratinocytes or basal and suprabasal are related

[25]. This disease is not unique to dogs, so different subtypes of EBS have also been observed in humans, and different genes play a role

[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. However, in dogs, only two genes have been associated with it. The mutation of the

PLEC gene has been associated so far with EBS in Eurasier dogs

[25]. The product of the

PLEC gene is plectin, a 500 kDa protein found in skin and other tissues, such as bone, muscle, and the nervous system

[37]. There are likely different isoforms of plectin that are cell-type dependent and/or developmentally regulated

[38]. Mauldin et al. (2017) demonstrated that in dogs with a homozygous G-to-A variant in the

PLEC gene, a tryptophan is converted to a premature stop codon in exon 27, resulting in this disease with autosomal recessive inheritance

[39]. On the other hand, Olivry et al. (2012) showed the association between a single mutation in the first intron of

PKP1 gene. This single mutation results in a premature stop codon, and the absence of the protein plakophilin-1, a protein that stabilizes desmosomes in the skin

[40][41][40,41]. The inheritance of this mutation was also autosomal recessive, and this detection occurred in dog breed Chesapeake Bay Retriever, resulting in an ectodermal dysplasia-skin fragility syndrome

[40].

In epidermolysis bullosa junctional (EBJ), cleft formation occurs through the lamina lucida of the basement membrane zone. Affected individuals exhibit blisters, deep erosions, and ulcers

[22]. In humans, mutations in several genes have been associated with this pathology, including genes encoding subunits of integrins (

ITGA6,

ITGB4, and

ITGA3), collagen (

COL17A1), and laminin 332 (

LAMA3,

LAMB3, and

LAMC2)

[42][43][42,43]. Recently, mutations in the

LAMA3 and

LAMB3 genes have been associated with EBJ in Australian shepherd dogs

[11][26][11,26]. In the study by Kiener et al. (2020), a

LAMB3:c.1174T > C mutation was reported as the cause of EBJ, suggesting an autosomal recessive inheritance of this mutation

[11]. The

LAMB3 gene encodes the β3-polypeptide chain of laminin-1

[44] and has been associated with the progression of several human tumors

[45]. The recent study by Herrmann et al. (2021) reported a

LAMA3 mutation associated with EBJ and severe upper respiratory disease in Australian Shepherd dogs

[26]. This mutation (Asp2867Val) results in a missense variant in the laminin-α3 chain with autosomal recessive inheritance. Other mutations in the same gene have been found in the German Pointer dog breed associated with EBJ. Specifically, an insertion of repetitive satellite DNA in intron 35 of this gene has been associated with EBJ

[10][27][10,27]. This insertion results in an α3-pre-messenger RNA that is not well matured and a decrease in laminin 5 expression, thereby impairing adhesion and the clonogenic potential of the EBJ keratinocytes.

Finally, in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB), blistering occurs in the sublamina densa, and the skin and mucosa are extremely sensitive. The blisters heal with scarring, and end with progressive disability and the deformation of the fingers

[46]. This disease, which affects dogs, sheep, cattle, cats, and humans, is caused by mutations in the

COL7A1 gene, which encodes collagen type VII

[47]. A total of 500 mutations of this gene have been associated with DEB, and the severity of the phenotype depends on the type of mutations and their location

[48]. Most of these mutations were observed in the golden retriever, although Nagata et al. (1995) reported a case of DEB in Akita Inu dog breed

[12]. The authors did not perform a genetic study on the animal, and the results they observed when analyzing the bladders by electronic microscopy and immunohistochemistry were comparable to those in humans and other dogs suffering with this disease

[12]. Several studies reported new therapies to control and eradicate this disease. In one study, canine keratinocytes were used to generate autologous epidermal layers in dogs with homozygous missense mutation in the

COL7A1 gene, which expressed an aberrant protein, with good results

[49]. Other authors attempted gene therapy with retroviral vectors

[50]. Recently, Gretzmeier et al. (2021) published good results when recombinant protein collagen VII (C7) was administered to mice and dogs

[51].