Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) morbidity and mortality are decreasing in high-income countries, but ASCVD remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in high-income countries. Over the past few decades, major risk factors for ASCVD, including LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), have been identified. Statins are the drug of choice for patients at increased risk of ASCVD and remain one of the most commonly used and effective drugs for reducing LDL cholesterol and the risk of mortality and coronary artery disease in high-risk groups. Unfortunately, doctors tend to under-prescribe or under-dose these drugs, mostly out of fear of side effects. The latest guidelines emphasize that treatment intensity should increase with increasing cardiovascular risk and that the decision to initiate intervention remains a matter of individual consideration and shared decision-making.

- statin

- cardiovascular disease

- atherosclerosis

- LDL-cholesterol

1. Introduction

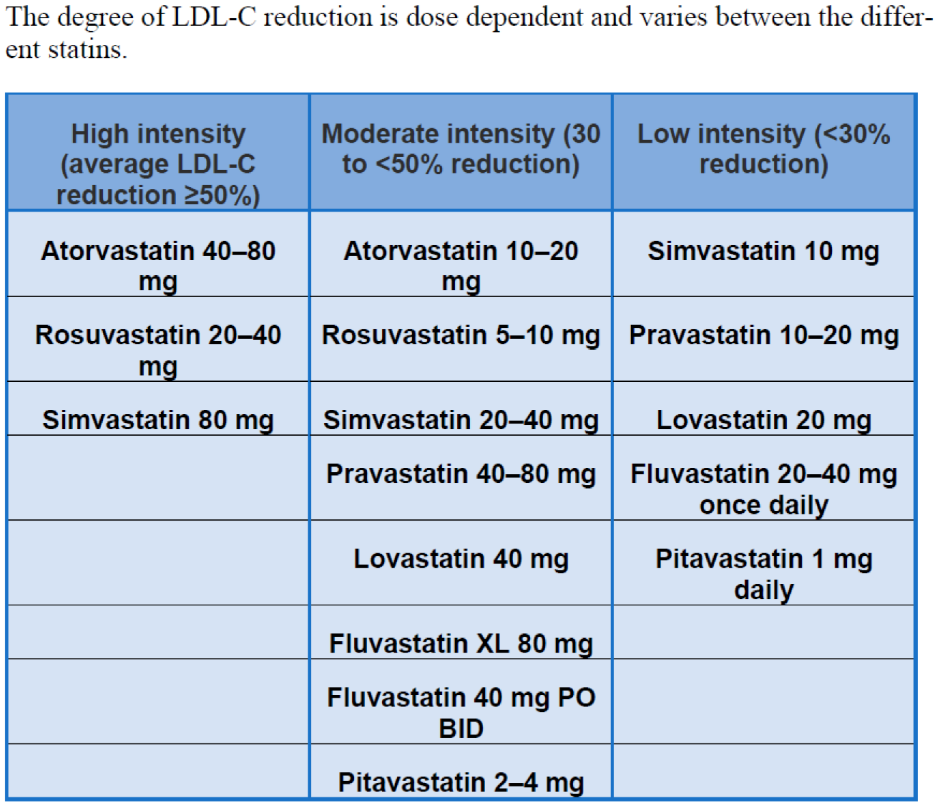

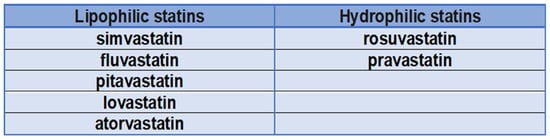

1.1. Are Statins All the Same?

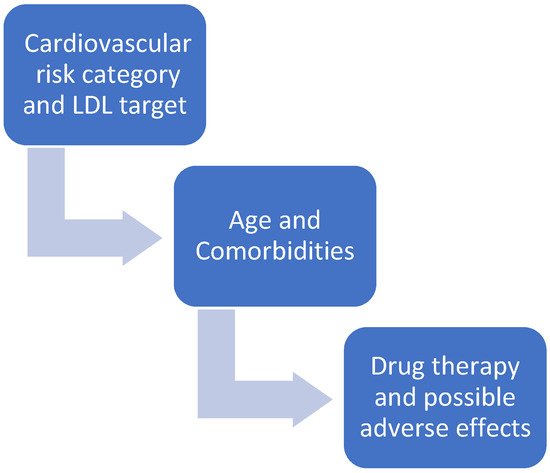

1.2. Cardiovascular Risk Category and LDL-C Target

| RISK CATEGORY. | WHICH PATIENT? | LDL-C TARGET |

|---|---|---|

| Very high-risk patients (10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality > 10%) | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) documented clinically or by imaging (acute coronary syndrome, stable angina, coronary revascularization, stroke or transient ischemic attack, peripheral arterial disease). Imaging documented ASCVD, including findings known to be relevant to the development of future clinical events, such as Diabetes mellitus (DM) with end-organ damage (microalbuminuria, retinopathy, and neuropathy) or at least 3 CV (cardiovascular) risk factors or early-onset type 1 diabetes that has been present for more than 20 years. Severe chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). |

LDL < 55 mg/dL or reduce LDL by at least 50% compared to baseline levels |

| Very very high-risk patients | Very high-risk patients who experience a second vascular event within 2 years of the first during therapy with statins at the highest tolerable dosage. | LDL < 40 mg/dL |

| High-risk patients (10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality 5–10%) | Particularly high individual risk factors, such as total cholesterol > 310 mg/dL (>8 mmol/L), LDL-C > 190 mg/dL (>4.9 mmol/L) or blood pressure ≥ 180/110 mmHg. Familial hypercholesterolemia without other CV risk factors. Diabetes mellitus without end organ damage, but present for at least 10 years or in conjunction with another CV risk factor. Chronic moderate kidney disease (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2). |

LDL < 70 mg/dL or reduce LDL values by at least 50% compared to the initial ones |

| Moderate risk patients (10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality > 1% <5%) | Diabetes in young subjects (T1DM < 35 years, T2DM < 50 years), present for less than 10 years and in absence of other risk factors | LDL < 100 mg/dL |

| Low-risk patients (risk of cardiovascular mortality at 10 years < 1%) | LDL < 116 mg/dL |

2. Statins and Cardiovascular Diseases

2.1. Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)

2.2. Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)

2.3. Heart Failure

2.4. Cardiac Valvulopathies

2.5. Stroke

3. Statins in Special Populations

3.1. Statins and Elderly People

3.2. Statins and Young People

3.3. Statins and Familial Dyslipidemias

3.4. Statins and Cognitive Impairment

References

- Tiwari, V.; Khokhar, M. Mechanism of action of anti-hypercholesterolemia drugs and their resistance. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 741, 156–170.

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188.

- Zhou, Q.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Circ. J. 2010, 74, 818–826.

- Schachter, M. Chemical, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of statins: An update. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 19, 117–125.

- Climent, E.; Benaiges, D.; Pedro-Botet, J. Hydrophilic or Lipophilic Statins? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 687585.

- Goh, I.X.; How, C.H.; Tavintharan, S. Cytochrome P450 drug interactions with statin therapy. Singap. Med. J. 2013, 54, 131–135.

- Benes, L.B.; Bassi, N.S.; Davidson, M.H. The Risk of Hepatotoxicity, New Onset Diabetes and Rhabdomyolysis in the Era of High-Intensity Statin Therapy: Does Statin Type Matter? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 59, 145–152.

- Sakamoto, T.; Kojima, S.; Ogawa, H.; Shimomura, H.; Kimura, K.; Ogata, Y.; Sakaino, N.; Kitagawa, A. MUSASHI-AMI Investigators. Usefulness of hydrophilic vs. lipophilic statins after acute myocardial infarction: Subanalysis of MUSASHI-AMI. Circ. J. 2007, 71, 1348–1353.

- Izawa, A.; Kashima, Y.; Miura, T.; Ebisawa, S.; Kitabayashi, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Sakurai, S.; Kagoshima, M.; Tomita, T.; Miyashita, Y.; et al. Assessment of Lipophilic vs. Hydrophilic Statin Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ. J. 2014, 79, 161–168.

- Atoh, K.; Ichihara, K. Lipophilic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors increase myocardial stunning in dogs. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000, 35, 256–262.

- Bytyçi, I.; Bajraktari, G.; Bhatt, D.L.; Morgan, C.J.; Ahmed, A.; Aronow, W.S.; Banach, M. Hydrophilic vs. lipophilic statins in coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2017, 11, 624–637.

- Stone, N.J.; Robinson, J.G.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Merz, C.N.B.; Blum, C.B.; Eckel, R.H.; Goldberg, A.C.; Gordon, D.; Levy, D.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2889–2934.

- Jones, P.; Kafonek, S.; Laurora, I.; Hunninghake, D.; for the CURVES Investigators. Comparative Dose Efficacy Study of Atorvastatin Versus Simvastatin, Pravastatin, Lovastatin, and Fluvastatin in Patients with Hypercholesterolemia (The CURVES Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 81, 582–587.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration; Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Emberson, J.; Holland, L.E.; Reith, C.; Bhala, N.; Collins, R. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170 000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010, 376, 1670–1681.

- Rosenson, R.S.; Tangney, C.C. Antiatherothrombotic properties of statins: Implications for cardiovascular event reduction. JAMA 1998, 279, 1643–1650.

- Wang, C.Y.; Liu, P.Y.; Liao, J.K. Pleiotropic effects of statin therapy: Molecular mechanisms and clinical results. Trends Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 37–44.

- Davies, M.J. Stability and instability: Two faces of coronary atherosclerosis. The Paul Dudley White Lecture 1995. Circulation 1996, 94, 2013–2020.

- Weissberg, P.L.; Clesham, G.J.; Bennett, M.R. Is vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation beneficial? Lancet 1996, 347, 305–307.

- Flex, A.; Biscetti, F.; Iachininoto, M.G.; Nuzzolo, E.R.; Orlando, N.; Capodimonti, S.; Angelini, F.; Valentini, C.G.; Bianchi, M.; Larocca, L.M.; et al. Human cord blood endothelial progenitors promote post-ischemic angiogenesis in immunocompetent mouse model. Thromb. Res. 2016, 141, 106–111.

- Biscetti, F.; Gaetani, E.; Flex, A.; Straface, G.; Pecorini, G.; Angelini, F.; Stigliano, E.; Aprahamian, T.; Smith, R.C.; Castellot, J.J.; et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is crucial for iloprost-induced in vivo angiogenesis and vascular endothelial growth factor upregulation. J. Vasc. Res. 2009, 46, 103–108.

- Pasceri, V.; Patti, G.; Nusca, A.; Pristipino, C.; Richichi, G.; Di Sciascio, G.; ARMYDA Investigators. Randomized trial of atorvastatin for reduction of myocardial damage during coronary intervention: Results from the ARMYDA (Atorvastatin for Reduction of MYocardial Damage during Angioplasty) study. Circulation 2004, 110, 674–678.

- Winchester, D.E.; Wen, X.; Xie, L.; Bavry, A.A. Evidence of pre-procedural statin therapy a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1099–1109.

- Patti, G.; Cannon, C.P.; Murphy, S.A.; Mega, S.; Pasceri, V.; Briguori, C.; Colombo, A.; Yun, K.H.; Jeong, M.H.; Kim, J.-S.; et al. Clinical benefit of statin pretreatment in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A collaborative patient-level meta-analysis of 13 randomized studies. Circulation 2011, 123, 1622–1632.

- Patti, G.; Pasceri, V.; Colonna, G.; Miglionico, M.; Fischetti, D.; Sardella, G.; Montinaro, A.; Di Sciascio, G. Atorvastatin pretreatment improves outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing early percutaneous coronary intervention: Results of the ARMYDA-ACS randomized trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1272–1278.

- Di Sciascio, G.; Patti, G.; Pasceri, V.; Gaspardone, A.; Colonna, G.; Montinaro, A. Efficacy of atorvastatin reload in patients on chronic statin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: Results of the ARMYDA-RECAPTURE (Atorvastatin for Reduction of Myocardial Damage During Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 558–565.

- Sousa, A.C.S.; Baldissera, F.; Nascimento, B.R.; Giraldez, R.R.C.V.; Cavalcanti, A.B.; Pereira, S.B.; Mattos, L.A.; Armaganijan, L.V.; Guimarães, H.P.; Sousa, J.E.M.R.; et al. Effect of Loading Dose of Atorvastatin Prior to Planned Pe cutaneous Coronary Intervention on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Acute Coronary Syndrome: The SECURE-PCI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 1331–1340.

- Navarese, E.P.; Gurbel, P.A.; Andreotti, F.; Kołodziejczak, M.M.; Palmer, S.C.; Dias, S.; Buffon, A.; Kubica, J.; Kowalewski, M.; Jadczyk, T.; et al. Prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiovascular procedures-a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168726.

- Foody, J.M.; Roe, M.T.; Chen, A.Y.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Brindis, R.G.; Peterson, E.D.; Gibler, W.B.; Ohman, E.M.; CRUSADE Investigators. Lipid management in patients with unstable angina pectoris and non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (from CRUSADE). Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 95, 483–485.

- Tonelli, M.; Bohm, C.; Pandeya, S.; Gill, J.; Levin, A.; Kiberd, B.A. Cardiac risk factors and the use of cardioprotective medications in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2001, 37, 484–489.

- Natanzon, S.S.; Matetzky, S.; Beigel, R.; Iakobishvili, Z.; Goldenberg, I.; Shechter, M. Statin therapy among chronic kidney disease patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2019, 286, 14–19.

- Boccara, F.; Miantezila Basilua, J.; Mary-Krause, M.; Lang, S.; Teiger, E.; Steg, P.G.; Guiguet, M. Statin therapy and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction in HIV-infected individuals after acute coronary syndrome: Results from the PACS-HIV lipids substudy. Am. Heart J. 2017, 183, 91–101.

- Lake, J.E.; Currier, J.S. Metabolic disease in HIV infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 964–975.

- Ownsend, M.L.; Hollowell, S.B.; Bhalodia, J.; Wilson, K.H.; Kaye, K.S.; Johnson, M.D. A comparison of the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapy between HIV- and non-HIV-infected subjects with hyperlipidaemia. Int. J. STD AIDS 2007, 18, 851–855.

- Heald, C.L.; Fowkes, F.G.R.; Murray, G. Price JF on behalf of the International ABI Collaboration. Risk of mortality and cardiovascular disease associated with the ankle-brachial index: Systematic review. Atherosclerosis 2006, 189, 61–69.

- Subherwal, S.; Patel, M.R.; Kober, L.; Peterson, E.D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Gislason, G.H.; Olsen, A.M.; Jones, W.S.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Fosbol, E.L. Peripheral artery disease is a coronary heart disease risk equivalent among both men and women: Results from a nationwide study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 317–325.

- Foley, T.R.; Singh, G.D.; Kokkinidis, D.G.; Choy, H.K.; Pham, T.; Amsterdam, E.A.; Rutledge, J.C.; Waldo, S.W.; Armstrong, E.J.; Laird, J.R. High-Intensity Statin Therapy Is Associated with Improved Survival in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005699.

- Liao, J.K.; Laufs, U. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 89–118.

- Biscetti, F.; Porreca, C.F.; Bertucci, F.; Straface, G.; Santoliquido, A.; Tondi, P.; Angelini, F.; Pitocco, D.; Santoro, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; et al. TNFRSF11B gene polymorphisms increased risk of peripheral arterial occlusive disease and critical limb ischemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 1025–1032.

- Davignon, J. Beneficial cardiovascular pleiotropic effects of statins. Circulation 2004, 109, III-39–III-43.

- Treasure, C.B.; Klein, J.L.; Weintraub, W.S.; Talley, J.D.; Stillabower, M.E.; Kosinski, A.S.; Zhang, J.; Boccuzzi, S.J.; Cedarholm, J.C.; Alexander, R.W. Beneficial effects of cholesterol-lowering therapy on the coronary endothelium in patients with coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 481–487.

- Arya, S.; Khakharia, A.; Binney, Z.O.; DeMartino, R.R.; Brewster, L.P.; Goodney, P.P.; Wilson, P.W.F. Association of Statin Dose with Amputation and Survival in Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. Circulation 2018, 137, 1435–1446.

- Bielecka-Dabrowa, A.; Bytyçi, I.; Von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.; Jozwiak, J.; Rysz, J.; Hernandez, A.V.; Bajraktari, G.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Banach, M. Association of statin use and clinical outcomes in heart failure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 188.

- Ferro, D.; Parrotto, S.; Basili, S.; Alessandri, C.; Violi, F. Simvastatin inhibits the monocyte expression of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with hypercholesterolemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 427–431.

- Laufs, U.; La Fata, V.; Plutzky, J.; Liao, J.K. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation 1998, 97, 1129–1135.

- Hayashidani, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Shiomi, T.; Suematsu, N.; Kinugawa, S.; Ide, T.; Wen, J.; Takeshita, A. Fluvastatin, a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor, attenuates left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation 2002, 105, 868–873.

- Almeida, S.O.; Budoff, M. Effect of statins on atherosclerotic plaque. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 29, 451–455.

- Dechend, R.; Fiebeler, A.; Park, J.K.; Muller, D.N.; Theuer, J.; Mervaala, E.; Bieringer, M.; Gulba, D.; Dietz, R.; Luft, F.C.; et al. Amelioration of angiotensin II–induced cardiac injury by a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor. Circulation 2001, 104, 576–581.

- Khush, K.K.; Waters, D.D.; Bittner, V.; Deedwania, P.C.; Kastelein, J.J.; Lewis, S.J.; Wenger, N.K. Effect of high-dose atorvastatin on hospitalizations for heart failure: Subgroup analysis of the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Circulation 2007, 115, 576–583.

- Remme, W.J. Overview of the relationship between ischemia and congestive heart failure. Clin. Cardiol. 2000, 23, IV4–IV8.

- Preiss, D.; Campbell, R.T.; Murray, H.M.; Ford, I.; Packard, C.J.; Sattar, N.; Rahimi, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Waters, D.D.; LaRosa, J.C.; et al. The effect of statin therapy on heart failure events: A collaborative meta-analysis of unpublished data from major randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 1536–1546.

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 891–975.

- Kjekshus, J.; Apetrei, E.; Barrios, V.; Böhm, M.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Cornel, J.H.; Dunselman, P.; Fonseca, C.; Goudev, A.; Grande, P.; et al. Rosuvastatin in older patients with systolic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2248–2261.

- Tavazzi, L.; Maggioni, A.P.; Marchioli, R.; Barlera, S.; Franzosi, M.G.; Latini, R.; Lucci, D.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Porcu, M.; Tognoni, G.; et al. Investigators Effect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 1231–1239.

- Olsson, M.; Thyberg, J.; Nilsson, J. Presence of oxidized low density lipoprotein in nonrheumatic stenotic aortic valves. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 1218–1222.

- Otto, C.M.; Kuusisto, J.; Reichenbach, D.D.; Gown, A.M.; O’Brien, K.D. Characterization of the early lesion of `degenerative’ valvular aortic stenosis: Histological and immunohistochemical studies. Circulation 1994, 90, 844–853.

- Novaro, G.M.; Tiong, I.Y.; Pearce, G.L.; Lauer, M.S.; Sprecher, D.L.; Griffin, B.P. Effect of hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors on the progression of calcific aortic stenosis. Circulation 2001, 104, 22052209.

- Greve, A.M.; Bang, C.N.; Boman, K.; Egstrup, K.; Forman, J.L.; Kesäniemi, Y.A.; Ray, S.; Pedersen, T.R.; Best, P.; Rajamannan, N.M.; et al. Effect Modifications of Lipid-Lowering Therapy on Progression of Aortic Stenosis (from the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (from the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 121, 739–745.

- Rossebo, A.B.; Pedersen, T.R.; Boman, K.; Brudi, P.; Chambers, J.B.; Egstrup, K.; Gerdts, E.; Gohlke-Barwolf, C.; Holme, I.; Kesaniemi, Y.A.; et al. Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1343–1356.

- Cowell, S.J.; Newby, D.E.; Prescott, R.J.; Bloomfield, P.; Reid, J.; Northridge, D.B.; Boon, N.A.; Scottish Aortic, S. Lipid Lowering Trial IoRI. A randomized trial of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in calcific aortic stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2389–2397.

- Chan, K.L.; Teo, K.; Dumesnil, J.G.; Ni, A.; Tam, J. Investigators, A. Effect of Lipid lowering with rosuvastatin on progression of aortic stenosis: Results of the aortic stenosis progression observation: Measuring effects of rosuvastatin (ASTRONOMER) trial. Circulation 2010, 121, 306–314.

- Thiago, L.; Tsuji, S.R.; Nyong, J.; Puga, M.E.; Gois, A.F.; Macedo, C.R.; Valente, O.; Atallah, Á.N. Statins for aortic valve stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 9, CD009571.

- Rutkovskiy, A.; Malashicheva, A.; Sullivan, G.; Bogdanova, M.; Kostareva, A.; Stensløkken, K.O.; Fiane, A.; Vaage, J. Valve Interstitial Cells: The Key to Understanding the Pathophysiology of Heart Valve Calcification. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006339.

- Rajamannan, N.M.; Subramaniam, M.; Caira, F.; Stock, S.R.; Spelsberg, T.C. Atorvastatin inhibits hypercholesterolemia-induced calcification in the aortic valves via the Lrp5 receptor pathway. Circulation 2005, 112, I229–I234.

- Flint, A.C.; Kamel, H.; Navi, B.B.; Rao, V.A.; Faigeles, B.S.; Conell, C.; Klingman, J.G.; Sidney, S.; Hills, N.K.; Sorel, M.; et al. Statin use during ischemic stroke hospitalization is strongly associated with improved poststroke survival. Stroke 2012, 43, 147–154.

- Flint, A.C.; Kamel, H.; Navi, B.B.; Rao, V.A.; Faigeles, B.S.; Conell, C.; Klingman, J.G.; Hills, N.K.; Nguyen-Huynh, M.; Cullen, S.P.; et al. Inpatient statin use predicts improved ischemic stroke discharge disposition. Neurology 2012, 78, 1678–1683.

- Amarenco, P.B.J.; Callahan, A., 3rd; GoldsTein, L.B.; Hennerici, M.; Rudolph, A.E.; Sillesen, H.; Simunovic, L.; Szarek, M.; Welch, K.M.; Zivin, J.A. Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 549–559.

- Hackam, D.G.; Woodward, M.; Newby, L.K.; Bhatt, D.L.; Shao, M.; Smith, E.E.; Donner, A.; Mamdani, M.; Douketis, J.D.; Arima, H.; et al. Statins and intracerebral hemorrhage: Collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2011, 124, 2233–2242.

- Biscetti, F.; Straface, G.; Bertoletti, G.; Vincenzoni, C.; Snider, F.; Arena, V.; Landolfi, R.; Flex, A. Identification of a potential proinflammatory genetic profile influencing carotid plaque vulnerability. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 374–381.

- McKinney, J.S. Statin therapy and the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage: A meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials. Stroke 2012, 43, 2149–2156.

- Vergouwen, M.D.; Vermeulen, M.R.Y. Hemorrhagic stroke in the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels study. Neurology 2009, 72, 1447–1448.

- Greenberg, S.M. Should Statins be Avoided after Intracerebral Hemorrhage? Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 573–579.

- Haussen, D.C.; Henninger, N.; Kumar, S.; Selim, M. Statin use and microbleeds in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2012, 43, 2677–2681.

- McGuinness, B.; O’Hare, J.; Craig, D.; Bullock, R.; Malouf, R.P. Cochrane review on ‘Statins for the treatment of dementia’. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 119–126.

- Fellstrom, B.C.; Jardine, A.G.; Schmieder RE, A.S.G. Rosuvastatin and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1395–1407.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2019, 393, 407–415.

- Strandberg, T.E. Role of Statin Therapy in Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Elderly Patients. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2019, 21, 28.

- Pola, R.; Flex, A.; Gaetani, E.; Pola, P.; Bernabei, R. The -174 G/C polymorphism of the interleukin-6 gene promoter and essential hypertension in an elderly Italian population. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2002, 16, 637–640.

- Ravnskov, U.; Diamond, D.M.; Hama, R.; Hamazaki, T.; Hammarskjöld, B.; Hynes, N.; Kendrick, M.; Langsjoen, P.H.; Malhotra, A.; Mascitelli, L.; et al. Lack of an association or an inverse association between low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010401.

- Lack of association between Alzheimer’s disease and Gln-Arg 192 Q/R polymorphism of the PON-1 gene in an Italian population. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2003, 15, 88–91.

- Strandberg, T.E.; Kolehmainen, L.V.A. Evaluation and treatment of older patients with hypercholesterolemia: A clinical review. AMA 2014, 312, 1136–1144.

- Giugliano, R.P.; Mach, F.; Zavitz, K.; Kurtz, C.; Im, K.; Kanevsky, E.; Schneider, J.; Wang, H.; Keech, A.; Pedersen, T.R.; et al. Cognitive function in a randomized trial of evolocumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 633–643.

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337.

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; De Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 139, e1046–e1081.

- Koskinas, K.C.; Windecker, S.; Räber, L. Regression of coronary atherosclerosis: Current evidence and future perspectives. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 26, 150–161.

- Tuzcu, E.M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Tutar, E.; Ziada, K.M.; Hobbs, R.E.; McCarthy, P.M.; Young, J.B.; Nissen, S.E. High prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic teenagers and young adults: Evidence from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation 2001, 103, 2705–2710.

- Nissen, S.E.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Schoenhagen, P.; Brown, B.G.; Ganz, P.; Vogel, R.A.; Crowe, T.; Howard, G.; Cooper, C.J.; Brodie, B.; et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 291, 1071–1080.

- Ridker, P.M.; Pradhan, A.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Libby, P.; Glynn, R.J. Cardiovascular benefits and diabetes risks of statin therapy in primary prevention: An analysis from the JUPITER trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 565–571.

- Ott, B.R.; Daiello, L.A.; Dahabreh, I.J.; Springate, B.A.; Bixby, K.; Murali, M.; Trikalinos, T.A. Do statins impair cognition? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 348–358.

- Yeboah, J.; Young, R.; McClelland, R.L.; Delaney, J.C.; Polonsky, T.S.; Dawood, F.Z.; Blaha, M.J.; Miedema, M.D.; Sibley, C.T.; Carr, J.J.; et al. Utility of Nontraditional Risk Markers in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 139–147.

- Carr, J.J.; Jacobs, D.R.; Terry, J.G.; Shay, C.M.; Sidney, S.; Liu, K.; Schreiner, P.J.; Lewis, C.E.; Shikany, J.M.; Reis, J.P.; et al. Association of coronary artery calcium in adults aged 32 to 46 years with incident coronary heart disease and death. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 391–399.

- Khera, A.V.; Chaffin, M.; Aragam, K.G.; Haas, M.E.; Roselli, C.; Choi, S.H.; Natarajan, P.; Lander, E.S.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1219–1224.

- Nordestgaard, B.G.; Chapman, M.J.; Humphries, S.E.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Masana, L.; Descamps, O.S.; Wiklund, O.; Hegele, R.A.; Raal, F.J.; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel; et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general population: Guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease: Consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 3478–3490.

- Pang, J.; Chan, D.C.; Watts, G.F. The Knowns and Unknowns of Contemporary Statin Therapy for Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2020, 22, 64.

- Ramaswami, U.; Humphries, S.E.; Priestley-Barnham, L.; Green, P.; Wald, D.S.; Capps, N.; Anderson, M.; Dale, P.; Morris, A.A. Current management of children and young people with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia-HEART UK statement of care. Atherosclerosis 2019, 290, 1–8.

- Orsi, A.; Sherman, O.; Woldeselassie, Z. Simvastatin-associated memory loss. Pharmacotherapy 2001, 21, 767–769.

- Pola, R.; Flex, A.; Gaetani, E.; Santoliquido, A.; Serricchio, M.; Pola, P.; Bernabei, R. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 K469E gene polymorphism and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2003, 24, 385–387.

- Peters, J.T.; Garwood, C.L.; Lepczyk, M. Behavioral changes with paranoia in an elderly woman taking atorvastatin. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 2008, 6, 28–32.

- Saher, G.; Simons, M. Cholesterol and myelin biogenesis. Subcell. Biochem. 2010, 51, 489–508.

- Langsjoen, P.H.; Langsjoen, A.M. The clinical use of HMG CoA-reductase inhibitors and the associated depletion of coenzyme Q10. A review of animal and human publications. Biofactors 2003, 18, 101–111.

- Papa, A.; Danese, S.; Urgesi, R.; Grillo, A.; Guglielmo, S.; Roberto, I.; Semeraro, S.; Scaldaferri, F.; Pola, R.; Flex, A.; et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 gene polymorphisms in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004, 8, 187–191.

- Di Paolo, G.; Kim, T.W. Linking lipids to Alzheimer’s disease: Cholesterol and beyond. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 284–296.