Although metal oxides are the most studied class of materials for many catalytic reactions, in recent years,

h-BN has received increased attention as a support of catalytically active species. BN nanomaterials are attractive due to their large specific surface area, high resistance to sedimentation in liquid media, relatively high thermal stability and corrosion resistance, and the ability to tune their structure and properties by doping, creating defects, or by surface functionalization. The use of

h-BN as a carrier can increase the activity of the catalyst compared to conventional supports. Due to their layered structure,

h-BN provides a high density of attached metal NPs, which leads to increased catalytic activity

[49][50][66,67]. BN has unshared electron pairs localized on nitrogen atoms, resulting in a polarized state. In addition, the electronic properties of

h-BN depend very strongly on impurities, the introduction of which makes it possible to reduce the band gap. One of the paradoxes of

h-BN is that, being a highly inert material, it has its own catalytic activity. This was clearly shown in the reaction of the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane

[51][68]. The available experimental and theoretical data indicate that the

h-BN surface acts as a driver of conversion

[52][53][54][69,70,71].

The combination of different functional properties in one material can lead to additional advantages in the implementation of catalytic processes. For example, by creating core–shell Co@

h-BN structures, it was possible to achieve a high activity and structural stability of Co NPs, and their ferromagnetic nature made it possible to carry out the hydrogenation of nitroarenes in aqueous media

[55][72]. Hexagonal BN acted as a protective layer, reducing the probability of Co NP agglomeration and, as a result, contributed to an increase in the active surface and adsorption of reagent molecules. The FeNiCo/

h-BN material was characterized as a highly active and selective catalyst for the hydrogenolysis of hydroxymethylfurfural

[56][73]. The high BE between the FeNi and Co NPs and the

h-BN support ensured the stability of the catalyst and the possibility of its reuse. The surface chemistry of the support in the heterogeneous catalyst significantly affects the material performance. It was shown that a large number of B-O and N-H groups in the Co/

h-BN catalyst leads to an enhanced CoO/

h-BN interaction, which prevents the reduction of Co oxide to active metal NPs

[57][74]. The low amount of functional groups leads to the formation of larger Co NPs due to the reduced BE. An increased adsorption of cinnamaldehyde was associated with a high concentration of NH groups. The interaction of

h-BN with active NPs can be enhanced by additional surface functionalization. Thus, the stability of catalytically active sites deposited on the

h-BN surface during the oxidative desulfurization of the fuel was increased by modifying

h-BN with an ionic liquid

[58][75]. The modification also led to an increase in the efficiency of catalyst recirculation due to the enhanced interaction of the acid with the

h-BN surface. The excellent catalytic properties of BN-based catalysts are largely due to the presence of defects. It was shown that the B-OH bonds formed at the edges of defective

h-BN flakes serve as anchor centers for Cu NPs

[59][76]. The strong interaction force resulted in a high resistance of Cu to sintering, which is usually difficult due to the low Hutting temperature of copper. The synthesized catalysts were tested in the reaction of ethanol dehydrogenation and showed a better ability to selectively form acetaldehyde compared to oxide counterparts (silica and alumina). The observed effect is explained by the difference in acetaldehyde binding: the

h-BN-based catalysts were able to adsorb ethanol strongly, whereas the interaction with acetaldehyde was weak. At the same time, oxide-supported catalysts showed a strong interaction with both ethanol and acetaldehyde. This behavior resulted in an excellent selectivity of

h-BN-based systems in the production of acetaldehyde.

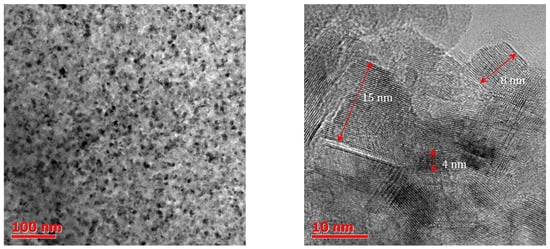

The high catalytic efficiency of many heterogeneous materials is associated with the small size of active centers. The small size of Ag NPs and their maximum density on the

h-BN surface were shown to be key parameters determining the high catalytic activity. Even a slight increase in the Ag NP size led to a noticeable deterioration in the catalytic performance in terms of offset and full conversion temperatures

[60][77]. Pt cluster-supported BNNSs (with 100 ppm of Pt) were characterized as a highly efficient catalyst for propane dehydrogenation with high propane conversion (~15%) and propylene selectivity (>99%) at a relatively low reaction temperature (520 °C)

[61][78]. To reduce the size of Pd NPs on an

h-BN support, it was proposed to use an intermediate MgO layer

[62][79]. It was found that, in addition to reducing the Pd size, Mg

2+ ions partially penetrate into the

h-BN crystal lattice, filling B vacancies. This contributed to an increase in oxygen adsorption and had a positive effect on the catalytic activity. The advantage of the metal oxide/BN interface was also demonstrated for the Ni/CeO

2/

h-BN system

[63][80], in which, Ni NPs were imbedded between cerium oxide and BN. The stability of Ni NPs was increased due to the metal/support interaction, which permitted reducing coke formation in the dry methane reforming reaction. The high CO

2 conversion rate observed on the Au/BN and Pt/BN catalysts is associated with better CO

2 adsorption on the oxidized BN surface. A charge density distribution at the Pt/

h-BN interface increases oxygen absorption, thereby accelerating oxygen-associated chemical reactions

[64][81].

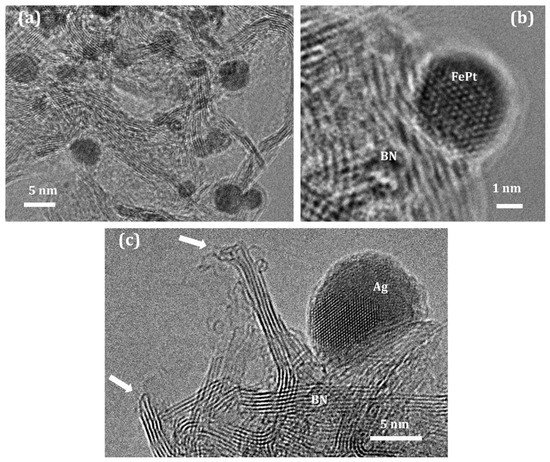

Fe

3O

4/BN, Fe

3O

4(Pt)/BN, and FePt/BN nanohybrids were obtained via polyol synthesis in ethylene glycol

[65][82]. BN supporting bimetallic FePt NPs demonstrated a significantly higher CO

2 conversion rate compared to Fe

3O

4/BN and Fe

3O

4(Pt)/BN counterparts and an almost 100% selectivity to CO, whereas catalysts with Fe

3O

4 NPs showed a better selectivity to hydrocarbons. An important result is the formation of core–shell

h-BN@FePt structures upon heating, which prevents the agglomeration of catalytically active NPs.

In the case of SMSI, the metal NP can be encapsulated in a carrier material. This can have both a positive and negative effect on the catalyst performance. Hexagonal BN rarely exhibits the SMSI effect due to its relative inertness; however, BO bonds present as surface functional groups can act as SMSI sites. SMSI between FeO

x and BO

x was observed in Fe/

h-BN catalysts, which led to the coordination of reduction and oxidation processes during the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene to styrene

[66][83]. As with oxide supports, SMSI can be customized with redox cycles in Pt/

h-BN catalysts. It has been shown that the oxidative treatment of Pt/

h-BN at temperatures above 520 °C leads to the formation of BO

x species and their strong interaction with metal NPs

[67][84]. The formation of thin layers of boron oxide on top of Pt NPs was observed, which blocked low-coordinated Pt centers. Encapsulated Pt NPs were resistant to sintering, and the particle size remained unchanged during catalysis. The Pt/

h-BN catalysts showed better stability in the propane dehydrogenation reaction compared to the Pt/Al

2O

3 counterpart due to the lower rate of coke formation. The surface oxygen-terminated groups of

h-BN can lead to too strong an interaction between the active phase and the carrier and adversely affect the reducibility of metal oxide NPs. To overcome this drawback, Fe/

h-BN catalysts doped with Cu and Mn were synthesized for the Fischer–Tropsch process

[68][85]. Doping Fe/

h-BN with Mn promotes the reduction and formation of active iron carbides, while Cu lowers the Fe-O reduction temperature, creating more active sites for H

2 dissociation. The observed synergistic effect of the promoters increased the catalyst activities without reducing their stability. However, in some cases, too strong an active phase/

h-BN interaction is unfavorable, as in the case of an acid–base catalytic reaction such as the synthesis of dimethyl ether by dehydration of methanol

[69][86]. This reaction usually proceeds on Brønsted acid catalysts and is therefore sensitive to the number and strength of the acid sites. In this case,

h-BN is not an ideal carrier among SiO

2, TiO

2, ZrO

2, Al

2O

3, and CeO

2 due to the strong interaction between tungstosilicic acid and the support, which leads to a decrease in proton mobility and catalyst efficiency.

Elemental doping is an effective approach to band gap engineering. Doping with carbon makes it possible to control the chemical activity of

h-BN by changing the electron density near the Fermi level. Carbon-doped

h-BN showed increased activity in the condensation of benzaldehyde with malononitrile to benzylidenemalononitrile, surpassing the undoped

h-BN and C

3N

4 counterparts

[70][87]. The high activity is explained by the decrease in the desorption barrier of the reaction products due to carbon doping. The addition of Se to

h-BN has been shown to narrow the band gap and improve carrier generation and separation

[71][88].

A number of studies have shown that the direct interaction of the

h-BN support with the reaction products affects the catalytic characteristics. A comparison of Pd NP catalysts supported on

h-BN, Al

2O

3, and MgO showed that the adsorption of maleic anhydride on Pd centers is improved as a result of the Pd to carrier interaction, and the Pd/

h-BN system is characterized by increased adsorption on

h-BN, which has a direct effect on the increase in catalytic activity

[72][89]. The formation rate of succinic acid 6000 g/gkat/h at a selectivity of 99.7% on the Pd/

h-BN catalyst was higher than on their oxide-based counterparts. The catalytic activity can be increased due to the formation of hydroxyl groups on the

h-BN surface

[73][90]. For example, an increase in the sonication time made it possible not only to increase the loading of metal, which led to an increase in the reduction rate of 2-nitroaniline, but also to increase the activity of catalysts due to the formation of hydroxyl surface groups

[74][91]. However, in some cases, the relatively inert

h-BN surface provides high selectivity for target products. A comparison of Pt-catalysts on various supports during the hydrogenation of cinnamic aldehyde to cinnamic alcohol showed that the absence of acid–base sites on the

h-BN surface makes it an ideal candidate as a support for this reaction, since the process proceeds through a simple non-dissociative adsorption of cinnamic aldehyde. This results in a selectivity of over 85% towards cinnamyl alcohol. In the case of Al

2O

3 and SiO

2 supports with a large number of acid–base sites, the selectivity is hindered due to the multiple-adsorption regime of the reagent.

Hexagonal BN can affect the electronic structure of deposited metal NPs. It was shown that the location of Ru on the

h-BN edges leads to an increase in the hydrogenation activity due to the enhancement of interfacial electronic effects between Ru and the BN surface

[75][92]. Electron-enriched NPs showed high activity in the production of primary amines from carbonyl compounds without the need for excess ammonia. For practical application, it is very important to control the electron density. An important step in this direction is the work of Zhu et al.

[76][93], showing that the change in the electron density of Pt NPs is possible by adjusting the B and N vacancies in

h-BN. Pt NPs are located at the site of boron and nitrogen vacancies acting as Lewis acids and Lewis bases, respectively. Thus, the synthesis of a Pt/

h-BN nanohybrid with a predominance of nitrogen vacancies leads to an interfacial electronic effect that promotes O

2 adsorption, reduces CO poisoning, and increases the overall activity and stability of the catalyst in the CO oxidation reaction.

The 2D morphology of

h-BN allows it to be successfully utilized as a homogeneous catalyst in liquid heterogeneous catalytic reactions due to its good dispersibility and, hence, high specific surface area. To obtain a metal-free catalyst for the oxidative desulfurization of aromatic compounds, N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHPI) was covalently grafted to the

h-BN surface

[77][94]. The strong interaction between NHPI and

h-BN results in a high catalyst activity, selectivity and recyclability. Rana et al.

[78][95] covalently grafted a copper complex onto the surface of exfoliated BNNSs. To ensure the stability of the complex, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane was used as a covalent linker. Leaching tests showed that there was no depletion of Cu from the catalyst surface. The materials showed exceptional activity in the azide-nitrile cycloaddition reaction to produce the pharmaceutically important 5-substituted 1H-tetrazole.

Single-atom catalysts (SACs) that combine the advantages of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts are of great interest due to exceptionally high catalytic activity in a wide variety of industrially important catalytic reactions

[79][96]. To commemorate the 10th anniversary of the introduction of the term SACs, a recent review examined various single-atom–host combinations and related applications

[80][97]. From an economic point of view, it is highly desirable to reduce the content of expensive metals of the Pt group without compromising activity, selectivity, and stability. The chemical activity of

h-BN can be fine-tuned using lattice defect engineering. For example, during the cryogenic grinding of

h-BN powders, vacancies are formed that can serve as active centers for the spontaneous reduction of metal cations

[81][98]. The authors showed the possibility of the formation of single atoms and clusters of Ag, Au, Pt, Cu, and Fe on

h-BN defects. The nitrogen-containing B vacancy in

h-BN can effectively anchor and confine Pd atoms

[82][99]. Hexagonal BN was shown to be a suitable material for dispersing Cu-Pt clusters due to the abundant B-O species on its surface

[61][78]. Nanoscale clusters (1–2 nm) were active and stable in the catalytic dehydrogenation of propane to propylene.

It is important to note that the choice of support material should be carried out taking into account the catalytic reaction mechanism. For example, the study of catalysts in the oxidative dehydrogenation of alcohols showed that the support material should be able to accept and conduct electrons between catalytically active NPs

[83][100]. From this point of view,

h-BN was inferior to C and TiO

2 due to its high band gap.

Hexagonal BN also finds its application in a relatively new catalytic direction: microwave catalysis. Mo

2C/

h-BN nanomaterials were proposed as highly active H

2S decomposition catalysts

[84][101]. However, the role of the support in this area of catalytic processes is still poorly understood.

3.2. Photocatalysts and Electrocatalysts

Photocatalysis and electrocatalysis are alternative processes for efficient chemical transformations. In contrast to thermal catalysis, additional energy enters the system from an external source, which makes it possible to overcome the thermodynamic barrier and shift the chemical equilibrium towards the reaction products. In photocatalytic and electrocatalytic processes, materials, in addition to the ability to adsorb and activate chemical reagents, must be able to conduct electrons and be activated under the action of external energy. From this point of view,

h-BN is not an ideal material. Due to the high band gap, a relatively high energy is required to excite an electron and transfer it from the valence band to the conduction band. However, the combination of

h-BN with other materials proved to be effective in achieving high activity and stability.

The efficiency of the photodegradation of organic pollutants under visible light irradiation can be increased in the presence of

h-BN. For example, the addition of

h-BN to the ZnFe

2O

4 photocatalyst decreased the recombination rate of electron–hole pairs, which affected the efficiency of Congo red and tetracycline degradation

[85][102]. The incorporation of

h-BN into 2D Bi

2WO

6 flakes increased the rate of charge separation and reduced the electron–hole recombination

[86][103]. This increased the ability to degrade antibiotics by 1.87 times. The 2D/2D

h-BN/Bi

2WO

6 heterostructures also showed high activity in the antibiotic degradation

[87][104]. MoS

2/

h-BN/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) composites were developed and tested for water splitting under sunlight

[88][105]. The simultaneous presence of BN/rGO, which has a high structural stability and a large number of surface centers, and MoS

2 with a small band gap, provides a synergistic catalytic effect. The hydrogen evolution rate of 1490.3 µmol/h/g was 58.2 and 12.2 times higher than that of the BN/rGO and MoS

2 counterparts. The high catalytic activity and selectivity of

h-BN-based photocatalysts in the reaction of nitrate reduction under UV radiation was explained by the formation of photoelectrons and CO

2− radicals

[89][106]. BN provided a high concentration of adsorption sites with B atoms acting as Lewis acids, and its electronic configuration was well-suited for efficient nitrate reduction. The hexagonal BN support was shown to provide a sink of excited electrons from the surface of catalytically active Cu

3P nanoparticles, making them active on the

h-BN surface for the adsorption of reagent molecules

[90][107]. BN was characterized as a promising catalyst for organic degradation via the activation of peroxymonosulfate. The defect-driven non-radical oxidation of porous

h-BN nanorods was proposed as the main mechanism of sulfamethoxazole degradation via the formation of singlet oxygen (

1O

2)

[91][108]. Used BN was easily regenerated upon heating in air, which completely recovered the B–O bonds.

a-MoS

xO

y/

h-BN

xO

y nanomaterial with a tuned MoS

xO

y zonal structure for photoinduced water splitting was developed

[92][109]. The nanohybrid showed high activity in the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB) (5.51 mmol g

−1 h

−1 under illumination with a mercury lamp), four times higher than that of known non-metallic catalysts. The obtained photocatalyst is very stable and can be reused. Oxygen-substituted BN has good wettability, and the interaction of oxygen defects with sulfur leads to the formation of S-doped BN, which has a high photodegradation efficiency when illuminated with visible light

[93][110].

To adapt the commercial PtRu/C electrocatalyst as an anode in fuel cells with a proton-exchange membrane, metal NPs on a carbon support were encapsulated in few-layers

h-BN

[94][111]. The

h-BN shell weakened the CO adsorption on the PtRu surface and increased the resistance to CO in H

2-O

2 fuel cells. The structural stability of Mo

2N electrocatalysts for the nitrogen reduction reaction was improved by combining molybdenum nitride with

h-BN

[95][112]. The optimal catalyst exhibited a NH

3 yield rate of 58.5 µg/h and a Faraday efficiency of 61.5%. By designing

h-BN defects, an optimum conversion rate was achieved at a lower overvoltage. Carbon-doped

h-BN was used to create enzyme-like single-atom Co electrocatalysts for the dechlorination reaction

[96][113]. Locally polarized B-N bonds played a key role in the adsorption of organochlorine compounds, improving the electrocatalytic activity. No such effect was observed on carbon and graphite supports doped with nitrogen.

Heterojunctions in

h-BN-doped BiFeO

3 and MnFeO

3 perovskite-based catalysts exhibited an extended visible light range, reduced band gap energy, and low recombination rate, and had excellent photocatalytic activity towards various antibiotics and dyes. The good photocatalytic performance of heterojunctions was explained by an extended excitation wavelength and a slow recombination rate of charge carriers

[97][114].

In conclusion,

reswe

archers note the important role of the

h-BN carrier, which, interacting with surface NPs, can increase their structural stability and change their electron density, which affects the catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability. Hexagonal BN can also be directly involved in chemical reactions, creating additional sites for component activation. All of these effects can have a positive or negative effect depending on the type of reaction, which is quite consistent with the well-known Sabatier–Balandin principle. Therefore, when designing a catalytic system, one should take into account the mechanisms of catalytic reactions.

4. Materials for Biomedicine and Improvement of Quality of Life

4.1. Biocompatibility and Dose-Dependent Toxicity

The biocompatibility and bio-application of BN nanomaterials have recently been reviewed

[98][115]. Available data indicate that the biocompatibility of BN depends on the concentration, size, and shape of BNNPs. In earlier studies, the cytocompatibility of BN nanostructures was evaluated in relation to various cell cultures, such as kidneys, epithelium, human skin, ovarian, bone tissue, human carcinoma, human osteosarcoma, human lung epithelial adenocarcinoma, human neuroblastoma, and others. The results show that a concentration of BNNPs less than 40 μg/mL is safe for the vast majority of cell lines, regardless of the size (5–200 nm) and shape (nanospheres, NSs, NTs). Moreover, a low concentration of BNNPs can stimulate cell proliferation. The addition of BNNPs to differentiated NT-2 cells increased their viability by 6% (6.25 µg/mL) and 13% (3.12 µg/mL)

[99][116]. Low BN concentrations (10–100 μg/mL) increased the viability of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by 118% (

p < 0.05), while a NP concentration of 150 and 200 μg/mL had no significant effect on cell metabolism

[89][106]. This effect can be explained by the influence of NPs at their low concentration on oxidative stress. Radicals (°OH, °OOH) can react with proteins, enzymes, nucleic acids, and other cell biomolecules, causing their damage and cellular apoptosis. Recently, it was shown that

h-BN can slowly dissolve in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysosome mimicking solution, while the released boron can form boric acid

[100][117], which exhibits antioxidant and antiapoptotic effects

[101][102][103][118,119,120]. Boric acids and their esters are cleaved by H

2O

2 and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) to form the corresponding alcohol and boric acid, which are considered nontoxic to human cells

[104][121]. The effect of BNNPs on cell viability (mHippo E-14 cells) was assessed in the presence of doxorubicin (DOX) at a concentration high enough to cause cellular stress but low enough not to kill all cells

[105][122]. The obtained results indicate that

h-BN reduces DOX-induced oxidative stress on cells at a concentration of 44 μg/mL.

The dose-dependent toxic effect of

h-BN NPs was studied in vivo in albino rats (Wistar) by measuring thiol/disulfide homeostasis, lipid hydroperoxide levels, and myeloperoxidase and catalase activity

[106][123]. After the intravenous administration of various BN doses, hematological and biochemical parameters did not change up to concentrations of 800 µg/kg. However, at doses of

h-BNNPs greater than 1600 μg/kg, significant damage to the liver, kidneys, heart, spleen, and pancreas was observed. The results showed that

h-BNNPs with a diameter of 120 nm are non-toxic and can be used in biomedical applications at low doses of 50 to 800 µg/kg.

4.2. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity

BNNPs and BN-based nanohybrids exhibit antibacterial and antifungal activity; some recent results are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1. Antibacterial activity of BN NPs and BN-based nanohybrids.

| Material |

BNNP Content (%) |

Pathogens |

Ref. |

| PNMPy-BNNPs |

10.0 |

E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis |

[107] |

| LDPE-BNNPs |

5.0–20.0 |

E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa,

S. epidermidis |

[108] |

| PHA/CH-BNNPs |

0.1–1.0 |

E. coli K1

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus |

[109] |

| QAC-BNNPs-PP |

3.0–10.0 |

E. coli Carolina #155065A

S. aureus Carolina #155556 |

[110] |

| CEL-BNNPs |

1.0–3.0 |

E. coli K12 (ATCC 29425)

S. epidermidis ATCC 49461 |

[111] |

| |

MIC of BN (mg/mL) |

|

|

| BNNPs |

15 |

Multidrug resistant E. coli (12 strains) |

[112] |

| BNNPs |

1.62 |

S. mutans 3.3 |

[113] |

| 400 |

S. mutans ATTC 25175 |

| 400 |

S. pasteuri M3 |

| 3.25 |

Candida sp. M25 |

| BNNPs |

256 |

E. coli |

[114] |

| 128 |

B. cereus |

| 128 |

S. aureus |

| 128 |

E. hirae |

| 128 |

P. aeruginosa |

| 256 |

L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophiia |

| 256 |

C. albicans |

| BNNSs |

100 |

E. coli DH5α |

[115] |