Fusarium head blight (FHB), or scab, caused by Fusarium species, is an extremely destructive fungal disease in wheat worldwide. In recent decades, researchers have made unremitting efforts in genetic breeding and control technology related to FHB and have made great progress, especially in the exploration of germplasm resources resistant to FHB; identification and pathogenesis of pathogenic strains; discovery and identification of disease-resistant genes; biochemical control, and so on. However, FHB burst have not been effectively controlled and thereby pose increasingly severe threats to wheat productivity. This review focuses on recent advances in pathogenesis, resistance quantitative trait loci (QTLs)/genes, resistance mechanism, and signaling pathways. We identify two primary pathogenetic patterns of Fusarium spe one of the most devastating and difficult fungal diseases in the world. It is cies and three significant signaling pathways mediated by UGT, WRKY, and SnRK1, reused by Fusarium spectively; many publicly approved superstar QTLs and genes are fully summarized to illustrate the pathogenetic patterns of Fusarium species, siges and is knownaling behavior of the major genes, and their sophisticated and dexterous crosstalk. Besides the research status of FHB resistance, breeding bottlenecks in resistant germplasm resources are also analyzed deeply. Finally, this review proposes that the maintenance of intracellular ROS (reactive oxygen species) homeostasis, regulated by several TaCERK-mediated theoretical patterns, may play an important role in plant response to FHB and puts forward some suggestions on resistant QTL/gene mining and molecular breeding in order to provide a valuable reference to contain FHB outbreaks in agricultural production and promote the sustainable development of green agricultureas the “cancer” of wheat.

- wheat

- fusarium head blight (FHB)

- pathogenesis

- resistance mechanism

- resistant QTL/genes

- signaling pathway

1. Introduction

2. Identification of Pathogenic Strains of Wheat FHB and Its Pathogenesis

- Discovery and Identification of Wheat Resistance Germplasm Resources

Germplasm resources are the basis of disease-resistance breeding. Since the 1920s, countries such as China, the USA, Korea, Japan, Argentina, Brazil, Switzerland, and the Czech Republic have made unremitting efforts in the identification and discovery of germplasm resources for resistance to FHB [3]. Since the outbreak of FHB in China in 1936, Chinese scientists have made great efforts in screening resistant germplasm resources. In 1974, the China Corporation of Research on Wheat Scab (CCRWS) carried out a nationwide screening of germplasm resources for resistance to FHB and identified 34,571 materials, including the common and wild wheat relatives. Only 1,796 common wheat varieties were recognized as high- or medium-resistant resources to FHB, including the accepted “Wang Shui Bai” and “Su Mai 3” [5]. In 1997, Wan et al. identified 276 materials of 80 species in 16 genera of wheat relatives and found that Roegneria (Roegneria tsukushiensis var. transiens and ciliaris) was the most resistant; Elymus, Kengyilia, Agropyron, Elytrigia, and so on were moderately resistant; Aegilops, Crithopsis, and Eremopyrum were susceptible [48]. However, Gagkaeva (2003) analysed nine species of Aegilops from warm and humid areas and found that Aegilops was a potential source of FHB resistance [49]. In addition, Brisco et al. (2017) identified more than 99 Aegilops species from areas with high levels of annual rainfall and further verified that Aegilops tauschii Coss was FHB-resistant [4]. Obviously, the differences in the results mentioned above may be attributed to the different research conditions. Gagkaeva (2003) identified the FHB resistance of 252 materials and found no relationship between ploidy and FHB resistance but a close correlationship between FHB resistance and the geographical origin of the materials. Wheat relatives from high-warmth and -humidity environments were FHB-resistant, while the resources from dry environments in Central Asia were highly susceptible to FHB [49]. With further research, more and more FHB-resistant resources have been found or identified again, such as Leymus racemosus Tzvelev (Elymus giganteus Vahl.) [50], Elymus tsukushiensis honda [51], Elytrigia elongata (Host) Nevsi [52], and so on. The results mentioned above demonstrate that FHB resistance of wheat ishows specificity in species and environments. The wheat wild relatives, such as Roegneria, Leymus racemosus, Elymus tsukushiensis, Elytrigia elongata, and Aegilops, are all potential FHB-resistant germplasm resources. Moreover, FHB resistance is closely related to the geographical origin of the materials in warm and humid areas.

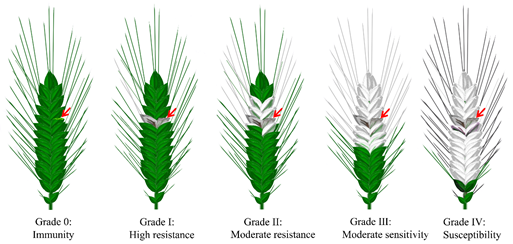

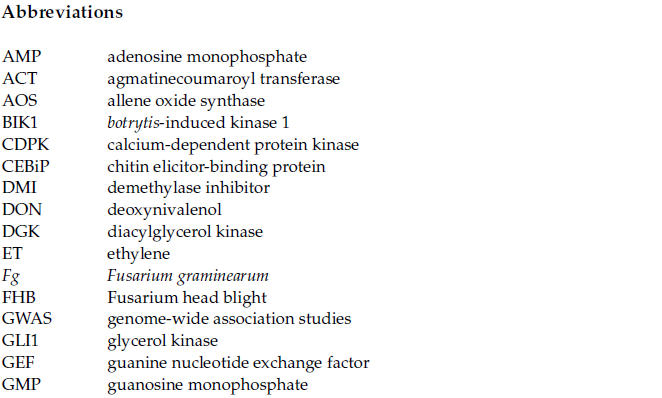

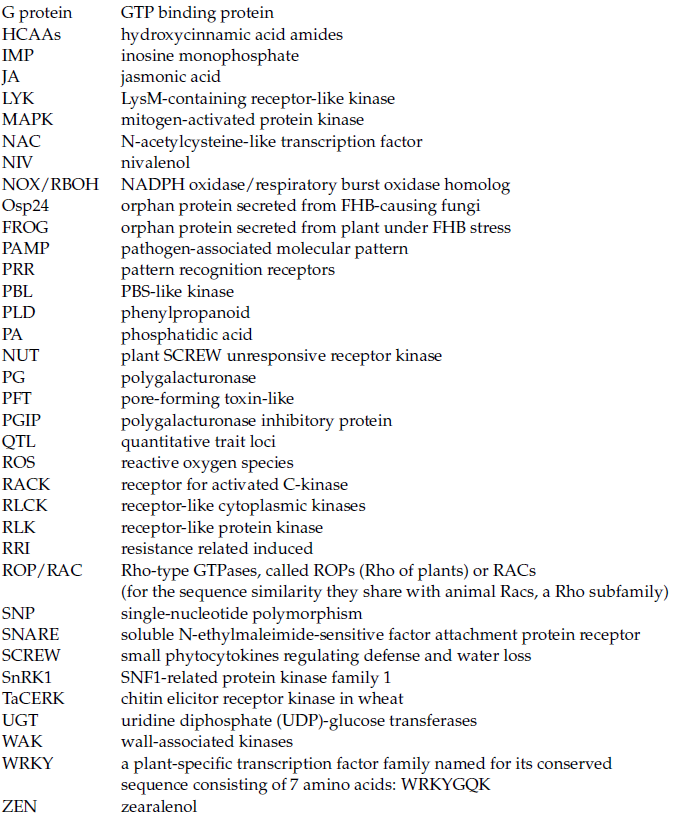

In summary, more than 50,000 wheat materials have been identified worldwide for resistance to FHB in the last 10 years. According to the incidence of FHB on wheat spikes, the severity of the disease was divided into five grades: 0, I~IV—from disease-free to mild to severe. Consistent with this, wheat germplasm resources are also classified into five grades according to their resistance to FHB (Figure 2). However, it is clear that, so far, almost all of the FHB-resistant germplasm resources selected globally are moderately susceptible, and none of them is completely immune to FHB [3]. The better resources, which had been identified as having good resistance to infestation and extension, were mainly found in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River in China, a region with a high incidence of FHB. For example, the resistant materials Yang Mai 158, Su Mai 3, Wang Shui Bai, Ning Mai 9, and dozens of wheat varieties derived from them all originated in these regions [53–55], while only Sumai 3 and its derivatives have been widely used for FHB-resistance breeding in China and abroad and have resulted in resistant varieties such as Ning 7840 [6], Alsen [7], CM 82,036 [9], and Saikai 165 [8]; most other highly resistant FHB germplasm resources have not been promoted for production and breeding, due to their poor agronomic traits. Even though several varieties have been promoted for production, only very few reach moderate resistance levels (e.g., Yang Mai 158 and Ning Mai 9), and very few reach high resistance levels [55]. In conclusion, the identification of FHB-resistant resources has made an important contribution to FHB resistance research worldwide, and a number of resistant germplasm resources have been discovered. However, the resistance levels of the existing resistant varieties still cannot compensate for the large yield losses in years of severe blast epidemics. Therefore, it is imperative to explore high-resistance germplasm resources and, especially, to excavate resistance materials from high-humidity and -rainfall environments.

Figure 2. Grades of resistance to and severity of FHB in wheat. According to the severity of FHB on wheat spikes, the severity of the disease and the resistance level of the plant were divided into five grades: grade 0, I~IV, which represents the percentage of diseased spikelets as zero, less than 1/4 (<25%), 1/4~1/2 (26−50%), 1/2~3/4 (51−75%), and more than 3/4 (>75%) in turn. Meanwhile, the numbers also correspond to the different FHB resistance levels of the plant. (Please refer to the detailed information in GB/T 1576-2011 of China). Red arrows indicate sites inoculated with Fg.

4. The Resistance Mechanism of Wheat to FHB

4.1. Morphological and Physiological Mechanisms of Wheat Response to FHB

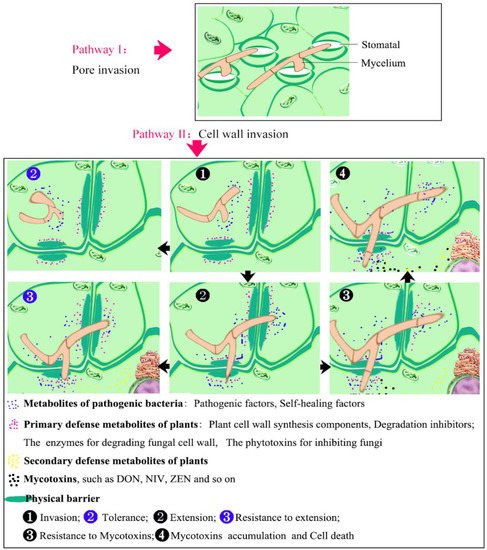

Where there is aggression, there is resistance. Study on the resistance mechanism of wheat to Fg is of great importance in controlling FHB and has become a major focus of attention for researchers. Based on the phenotype of resistance to FHB, plants have also been classified into five types: Type I, resistance to the initial infection; Type II, resistance to proliferation; Type III, seed resistance to infection; Type IV, tolerance to disease; and Type V, resistance to toxin accumulation [56,57]. All these resistance types can interact with each other to synergistically improve the overall resistance of wheat [58]. Among them, Type I and Type II have been more intensively studied, mainly in terms of the morphological and physiological mechanisms [59]. For example, many studies have demonstrated that the morphological characteristics—plant height, length of spike and flowering period, degree of anther extrusion, presence of awn, spike length and density, degree of glume opening, and degree of waxiness of the spike—are all correlated with FHB resistance against invasion [60,61]. More importantly, cytological studies showed that the pathogen-resistant varieties synergistically inhibited the expansion of the pathogen through forming papillae, reinforcing cell wall deposits, and increasing the biosynthesis of lignin, thionine, hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein, and hydrolase [62]. In addition, Liu et al. (2022) suggested that plants dynamically regulate stomatal reopening, mediated by the secreted peptides SCREWs and the receptor kinase NUT, to ensure a balanced physiological response at the whole-plant level in response to biotic stress [63].

It is well known that, when invaded by pathogenic fungi, plants synthesize different signaling molecules that stimulate the expression of disease-resistant genes through complex signaling pathways and thereby resist the invasion of pathogenic fungi. With progressive research, three hormone-mediated signaling pathways, jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and ethylene (ET), have come to be viewed as widely involved in plant biotic stresses [36,64,65]. The positive role of JA in FHB resistance has been demonstrated by studies [66,67]. For instance, a pore-forming toxin-like protein, PFT, may play a role in JA-mediated FHB resistance in a resistant wheat cultivar [68,69]. A wheat allene oxide synthase, TaAOS, is also involved in the JA signaling pathway to increase plant resistance to FHB, and the silenced strains exhibit a highly susceptible trait [70]. However, the roles of SA and ET in FHB resistance remain to be further demonstrated [71,72]. Furthermore, the specific signaling pathways involved in the response of the three hormones to FHB stress in plants have not been clarified. Nevertheless, some progress has been made, especially in the basic physical and physiological defense carried out by plants in response to FHB stress (Figure 1). However, FHB is caused by a mixture of Fusarium species and affected by genetic and environmental factors. FHB resistance is a quantitative trait that is controlled by multiple quantitative trait loci (QTL). Therefore, the number of resistance master genes which have been identified is still very limited, and the resistance mechanism is still unclear [73], which has seriously affected the research process of FHB resistance improvement.

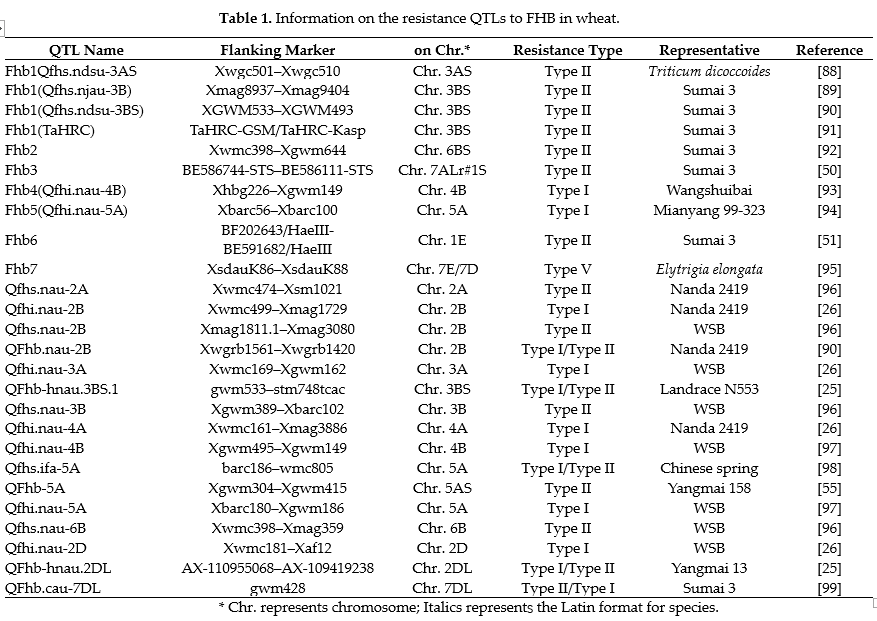

4.2. Resistance QTL in Plant to FHB

Analyzing the genetic loci of resistant germplasm resources and learning about their hereditary features is a prerequisite for applying high-quality resources to wheat genetic breeding. Numerous studies have shown that FHB resistance is a quantitative trait and is controlled by multiple genes. Early genetic studies were carried out by segregating progeny, estimating the resistance genes that different resistance parents might carry and the chromosomal localization of genes through chromosome engineering techniques. To date, many of the FHB-resistant QTLs in the representative resistance germplasm resources have been mapped onto all 21 wheat chromosomes (Table 1) [74]. Several important resistant seed resources of FHB have been used for chromosome mapping and functional analysis of QTLs by creating genetic populations such as the recombinant inbred lines (RIL) or double haploid lines (DHL). The advent of DNA markers and marker-based genetic mapping in the 1990s greatly facilitated the fine targeting of quantitative trait loci (QTL) or genes on genetic maps. For example, Li et al. (2019) finely localized the genetic locus of Qfhb.nau-2B in Nanda 2419 [75], and Jiang et al. (2020) localized the FHB resistance QTL QFhb-5A in Yangmai 158 [55]. In addition, the fungus-resistant locus in different wheat resistance strains, such as the Swiss wheat variety Arina [76]; Ernie [77] and Truman [78] in the USA; Dream [79] in Germany; T. macha [80] in Maga, Frontana [81] in Brazil; Chok-wang [82] in Korea; and Nyubai [83] and SYN1, a synthetic species bred by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), all have been identified by constructing genetic populations RILs or DHLs. Furthermore, with the application of bioinformatics technology and the continuous improvement of genomic data, the methods of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been used to excavate resistant loci/QTLs or associated genes [84]. To date, hundreds of FHB resistance QTLs have been identified on the 21 wheat chromosomes [74, However, most of them have minor or unstable effects, or their genetic loci and the molecular markers vary from one experiment to another. Moreover, the QTLs associated with type I resistance have low reproducibility due to different infection and identification methods and environmental conditions. Therefore, only a handful of QTLs, such as Fhb1, Fhb2, Fhb4, Fhb5, and Fhb7, have been finely localized and successfully employed in breeding programs [87], and very few QTLs associated with extension resistance have been finely localized and used in breeding. For detailed information on the superstar QTLs related to FHB resistance, please refer to Table 1.

Based on traditional breeding, molecular marker-assisted selection (MAS) is regarded as a useful tool for breeding, and it indeed improves the efficiency of selective breeding. However, due to linkage drag, the introduction of the FHB resistance QTLs is often accompanied by undesirable traits, which leads to certain difficulties for later genetic breeding.

4.3. Resistance Genes and Their Mechanisms in Response to FHB in Plant

So far, although hundreds of QTLs for FHB resistance have been mapped onto wheat chromosomes, it is a challenging task to segregate them using forward genetics. At present, the more well-defined QTLs for resistance to FHB in wheat are Qfhb.nau-2B [75], Fhb1~Fhb7 [85], Qfhs.ndsu-3AS [88], QFhb-5A [55], and so on (Table 1). Among them, the first identified and the best validated resistance QTL is Fhb1, which is employed as the most important FHB resistance donor worldwide [52,89]. Therefore, several approaches have been carried out to identify candidate genes in Fhb1 by transcriptome-based analysis and map-based cloning. For example, the genes encoding a pore-forming toxin-like proteinPFT [68,69], a laccase TaLAC4 [100], and a NAC (N-acetylcysteine) class transcription factor TaNAC032 [101] were all positioned within QTL-Fhb1 and conferred to FHB resistance. In addition, two putative histidine-rich calcium-binding proteins, TaHRC and Qfhs.njau-3B, were also found underlying in QTL-Fhb1, but they conferred FHB susceptibility. On the contrary, mutants of them conferred FHB resistance [52,89].

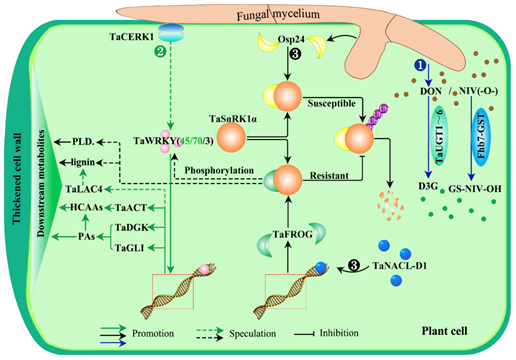

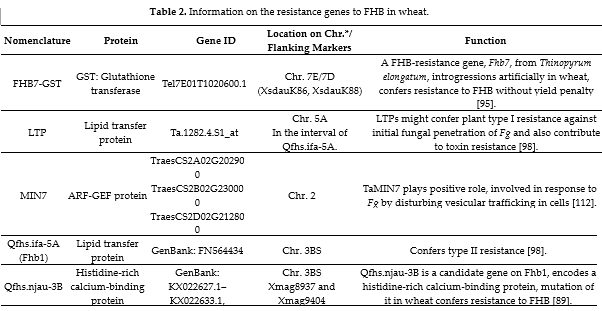

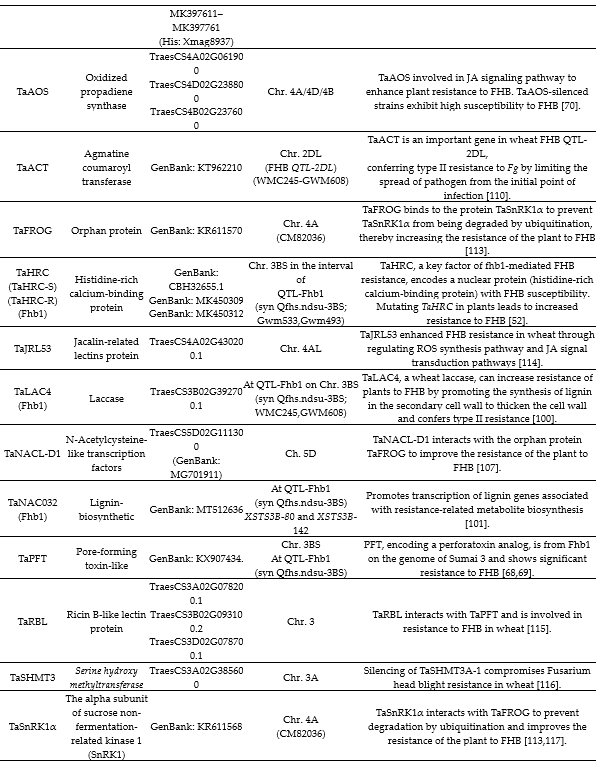

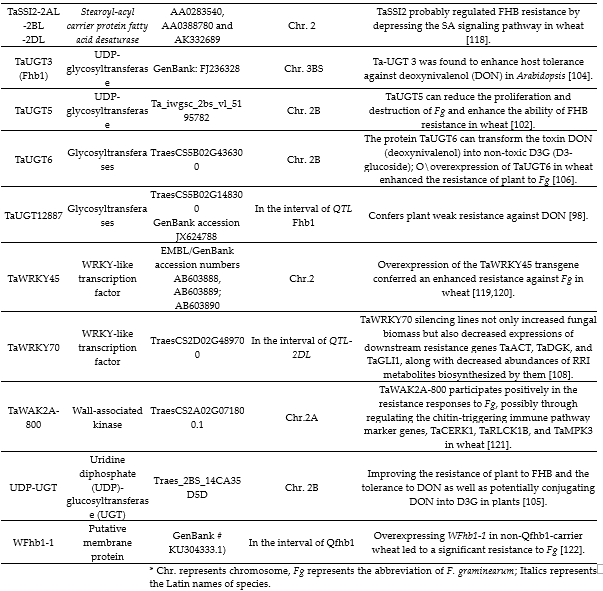

The advancement of genomics, proteomics, and metabonomics technologies has provided opportunities for identifying candidate genes and resolving the complex genetic mechanisms of FHB resistance. Therefore, a number of FHB-resistance genes have been reported (Figure 3 and Table 2). First of all, several uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucose transferases (UGTs) in wheat had been reported to be involved in FHB resistance in plants via cellular detoxification processes [98,102,103]. For example, TaUGT3 positively regulates the defense responses to FHB by converting DON to the less toxic DON-3-O-glucoside [104]; TaUGT4 was strongly induced by Fg or DON treatment according to transcriptional analysis [73]; Zhao et al. (2018) also proposed that TaUGT5 could reduce the proliferation and destruction of Fg and enhance the ability of FHB resistance in wheat [103]; another wheat TaUGT (Traes_2BS_14CA35D5D) was confirmed to enhance plant resistance to FHB and tolerance to DON as well as to potentially conjugate DON into D3G [105]. Later, a novel UGT gene, TaUGT6, was cloned and identified to enhance plant resistance to Fusarium by converting DON into D3G to some extent in vitro [106]. Secondly, another detoxification protein aglutathione S-transferase (GST), Fhb7, from a wheat relative, Elytrigia elongata, was reported to confer broad resistance and tolerance to Fusarium species by detoxifying trichothecenes, such as NIV, other than DON [95]. These results showed that detoxification mediated by uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucose transferases (UGTs) and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) is a crucial response of plants to resist FHB stress (Figure 3❶).

Figure 3. FHB-resistant signaling pathways in fungus–plant interactions. There are three resistant pathways: first, the detoxification pathway, in which the members of (UDP)-glucose transferase TaUGT1~6 can enhance plant tolerance to FHB by converting the fungal mycotoxin DON to the less toxic DON-3-O-glucoside, D3G (❶). In addition, another gene, Fhb7, encoding a glutathione S-transferase (GST), from a distant variety of wheat, Elytrigia elongata, confers broad resistance and tolerance to Fusarium species by detoxifying trichothecenes, such as NIV, through conjugating GSH to the epoxy group of NIV. Second are CERK1-mediated metabolic pathways to thicken the plant walls. It is well known that the first layer of innate immunity in plants is initiated by the surface-localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), in which the leading role is played by chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1 (CERK1), which mainly participates in chitin-induced immunity [107]. Meanwhile, chitin is a typical component of the fungal cell wall and can trigger the plant innate immune response by activating PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns). Here, a transcription factor, HvWRKY23, can be induced by HvCERK1 with some unclear methods upon infection with Fg. HvWRKY23 subsequently regulates downstream genes, such as HvPAL2, HvCHS1, HvHCT, HvLAC15, and HvUDPGT, to biosynthesize HCAAs, flavonoid glycosides, lignin, and so on, which reinforces the cell walls to contain the spread of Fg in plant cells. Similarly, TaWRKY70 was also identified as having a potential role against Fg in the early stages of defense through physically interacing with and activating the downstream genes TaACT, TaDGK, and TaGLI, among which TaACT is the rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of HCAAs and TaDGK and TaGLI are the crucial enzymes in the biosynthesis of PAs (phosphatidic acids) in plants [108]. Moreover, HCAAs and PAs have functions during fungus–plant interactions; PAs contribute to the plant defense response through translocation and catabolism in the apoplast, leading to the production of H2O2, which has several roles, such as directly eliminating pathogens and assisting in cell wall strengthening; HCAAs were identified as biomarkers during fungus–plant interactions and support a functional role in plant defense [109]. What is more, a guanidine cinnamyl transferase gene, TaACT, was confirmed as having a role involved in FHB response in plants [110]; another potential downstream gene, TaLAC4, encoding a wheat laccase, was also reported to restrain FHB infestation by promoting the synthesis of lignin in the secondary cell wall of plants in order to thicken the cell wall [100]. Therefore, this indicated that a signaling pathway of WRKY-mediated RRI metabolite accumulation in cells perhaps plays an important role in the plant response to FHB stress (❷). The second is an energy-related metabolic pathway. It is known that many pathogens have acquired the ability to inject virulence effector proteins into host cells to achieve more effective infection. As shown in ❸, FHB-causing fungi secrete a virulence effector protein, Osp24 (an orphan protein), which promotes mycelium growth and toxin accumulation in plant cells. At the same time, Osp24 can combine with TaSnRK1α, a FHB-resistant protein, resulting in TaSnRK1α being ubiquitinated and degraded. There is always an arms race between the pathogen and its host. For plants, the second layer of immune recognition is intracellular immune receptor forms, and the intracellular immune receptors are most often the nucleotide-binding proteins, which can recognize those effectors and elicit a second layer of defense. From this, it is not difficult to speculate that the N-acetylcysteine-like transcription factors, TaNACs (TaNACL-D1/TaNAC032), as the intracellular immune receptors, perhaps can recognize Osp24 or its analogs, and then are activated by them. Subsequently, the activated TaNACs regulate the expresion of the downstream gene TaFROG, which encodes a wheat orphan protein (an analog of Osp24). Thus, TaFROG can compete against Osp24 to combine with TaSnRK1α, preventing TaSnRK1α from being ubiquitinated and increasing plant resistance to FHB. However, the resistance mechanism of TaSnRK1α to FHB in plants still remains unclear. In addition, Han et al. found that SnRK1 interacts with and phosphorylates WRKY3 repressor in barley, leading to the degradation of WRKY3 and enhanced barley immunity [111]. Consequently, there may be molecular crosstalk between pathway ❷ and ❸ mediated by phosphorylation. PLD: phenylpropanoid; HCAAs: hydroxycinnamic acid amides; PAs: phosphatidic acids; TaACT: agmatinecoumaroyl transferase; TaDGK: diacylglycerol kinase; TaGLI: glycerol kinase.

Additionaly, there are some other FHB-resistance genes that have been identified. For instance, a transcription factor, TaWRKY45, was proved to enhance resistance to FHB in wheat, though the mechanism of resistance is still unknown [119,120]. TaWRKY70 was identified within the FHB-resistant QTL-2DL region and had a potential role against Fg in the early stages of defense through physically interacting with and activating the downstream genes TaACT, TaDGK, and TaGLI, among which TaACT was the rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of HCAAs (hydroxycinnamic acid amides), while TaDGK and TaGLI were the crucial enzymes in the biosynthesis of PAs (phosphatidic acids) in plants [108]. It should be added here that both HCAAs and PAs are instrumental in fungus–plant interactions. To be specific, PAs contribute to the plant defense response through translocation and catabolism in the apoplast, leading to the production of H2O2, which has several roles, such as directly eliminating pathogens and assisting in cell wall strengthening; HCAAs were identified as biomarkers during fungus–plant interactions and support a functional role in plant defense by reinforcing cell walls [109]. What is more, a guanidine cinnamyl transferase gene, TaACT, was also confirmed to have a role involved in FHB response in plants [110]. Similarly, in barley, HvWRKY23, induced by a chitin elicitor receptor kinase HvCERK1 [123], also fights FHB by regulating its downstream genes, such as HvPAL2, HvCHS1, HvHCT, HvLAC15, and HvUDPGT, to biosynthesize HCAAs and flavonoid glycosides [124]. Moreover, a potential downstream gene, TaLAC4, encoding a wheat laccase, was reported to restrain FHB infestation by promoting the synthesis of lignin in the secondary cell wall of plants in order to thicken the cell wall [100]. In addition, it is well known that the first layer of innate immunity in plants is initiated by the surface-localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), in which the leading role is played by chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1 (CERK1), which mainly participates in chitin-induced immunity [107]. Meanwhile, chitin is a typical component of the fungal cell wall and can trigger the plant innate immune response by activating PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns). Therefore, a signaling pathway of CERK1-WRKY-mediated RRI metabolite accumulation in cells perhaps plays an important role in plant response to FHB stress (Figure 3❷).

Approaches are different, but the results are satisfactory. A NAC-like transcription factor, TaNAC032, was also reported to enhance FHB resistance by reinforcing the secondary cell wall of plants through regulating resistance-related proteins and metabolites such as phenylpropanoid and lignin [101]. Meanwhile, another NAC (N-acetylcysteine), which was classed as a transcription factor, TaNACL-D1, can positively regulate the expression of a wheat orphan protein, TaFROG, and improve plant resistance to FHB [113]. On the other hand, TaFROG can interact with the FHB-resistance protein TaSnRK1α to protect it from degradation by deubiquitination, which, in turn, confers plant resistance to the fungal mycotoxin DON [125,126]. Interestingly, Jiang et al. (2020) found that an orphan protein, Osp24, which is secreted from FHB-causing fungi, competes against TaFROG for binding with the same region of TaSnRK1α and leads to the degradation of TaSnRK1α by ubiquitination [117]. To date, many studies have demonstrated that SnRK1, as the metabolic/energy sensor and signaling integrator, is involved in the plant response to diverse stress and energy conditions [111,127], though the resistance mechanism of TaSnRK1α to FHB in plants still remains unclear. Thus, the previously mentioned information indicates that NAC-TaFROG/Osp24-TaSnRKα-mediated RRI metabolites perhaps also perform crucial roles in the plant response to FHB stress through regulating energy-related metabolites, such as phenylpropanoid and lignin, which are also utilized in strengthening cell walls (Figure 3❸).

Besides the aforementioned genes/proteins, lipid transferase protein LTP [98] and its interacting protein TaRBL [115], ARF-GEF protein MIN7 [112], allene oxide synthase gene TaAOSb [70], histidine-rich calcium-binding protein TaHRC [52], putative membrane protein WFhb1-1 [122], wheat-wall associated kinases TaWAK2A-800 [121], serine hydroxymethyltransferase TaSHMT3A-1 [116],stearoyl-acyl carrier protein fatty acid desaturase TaSSI2 [118], Jacalin-related lectins protein TaJRL53 [114] were all excavated and proved to be positively involved in FHB response in plants (Table 2). In summary, the results mentioned above urged us to determine the pathways by which the FHB-resistant genes were involved in fungus–plant interactions. From Figure 3, we can see that there are three resistant pathways: TaUGT/Fhb-GST-mediated detoxicated pathway and TaWRKY- and TaSnRK1α-mediated metabolic pathways, respectively.

To sum up, with the advancement of biotechnology, more and more QTLs/genes for FHB resistance loci have been identified or clearly localized on the chromosomes. However, to date, only a few genes have been studied in depth; most genes were just functionally characterized, and very few resistance mechanisms and signaling pathways were pinpointed and explained. In addition, FHB is a complex quantitative trait, and a single gene phenotypic contribution ranges from 15% to 30% [54]. Thus, relying on only one, two, or very few resistance genes is not sufficient to effectively reduce damage, especially in years of severe epidemics. Therefore, an effective way, for restraining FHB burst, is to breed the resistant germplasm resources by unearthing multiple and pivotal FHB-resistance genes, revealing their resistance mechanisms, and then aggregating them and their synergistic resistance-related genes into varieties (lines) with better fecundity.

4.4. CERK1-mediated ROS Homeostasis Perhaps Performs a Vital Role in Response to FHB in Plant.

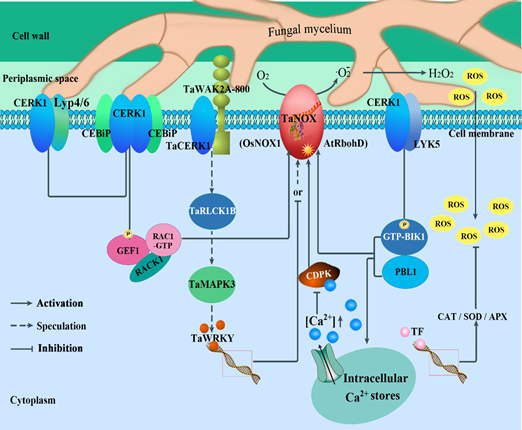

It is well known that ROS bursts are a common feature of plant response to external stresses [31,32], especially in the earlier stage of pathogen infection [11]. NADPH oxidase (NOX), also known as respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH), which is a key enzyme for ROS (·O2−, ·OH, H2O2) production in the intercellular matrix, has become the focus of current research on plant response to external stress. Previous studies on model plants have revealed that NOX is involved in a variety of signaling pathways which endow NOXs/RBOHs with powerful and versatile functions in plants to maintain innate immune homeostasis [128]. Moreover, many studies have indicated that some chitin-induced receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and/or receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases (RLCKs) can interact with NOXs/RBOHs directly or indirectly and phosphorylate the proteins to transmit pathogen signals during plant immunity [129,130]. Furthermore, several RLKs (CERK, LysM, and OsCEBiP) and RLCKs (BIK1 and small GTPase ROPs/RACs) and GEF-mediated immune signalings are all involved in ROS homeostasis by directly activating NOX in plants [107]. As early as 2011, Ding et al. found that the expression activity of NOX was significantly increased in the resistant variety “Wang Shui Bai” under FHB stress treatment but not in the susceptible varieties [131], suggesting that wheat NOX family members may play important roles in plant response to FHB stress. Accordingly, it is tempting to speculate that the chitin-induced particles CERK1, LYK, CEBiP, BIK1, and ROPs/RACs and GEF-mediated ROS homeostasis, by regulating NOX activity, perhaps perform a vital role in the plant response to FHB (as shown in Figure 4). In Arabidopsis, CERK1, a chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1, and LYK5, a LysM-containing receptor-like kinase 5, were found to be able to bind chitin and form a chitin-dependent complex, CERK1-LYK5 [132,133]. This is an immune complex in which AtCERK1 is involved in activating BIK1 by phosphorylation directly. After this, the activated BIK1 (GTP-BIK1) directly phosphorylates AtRbohD and enhances ROS production for defense responses [134,135]. In rice, OsCERK1, a plasma membrane-localized receptor-like kinase, is associated with receptor-like kinase OsCEBiP under chitin treatment [136]. In addition, OsCEBiP can form a homodimer upon chitin binding that is followed by heterodimerization with OsCERK1, creating a signaling-active sandwich-type receptor system [137,138]. Then, OsGEF1, a regulator functioning as a molecular switch, is phosphorylated by OsCERK1 [139]. The activated OsGEF1, coupling with OsRACK1 [140] in turn, phosphorylates a ROP/RAC GTPase, OsRAC1, and changes it from the RAC-GDP inactive form to the RAC-GTP active form [130,141]. Finally, OsRAC1 is involved in the OsCERK1/OsCEBiP-mediated immune signaling; it activates OsRbohB (OsNOX1) for ROS production by directly interacting with the N-terminus of NADPH oxidase [142,143]. Additionally, WAK2A-800 was shown to be positively involved in the responses to Fg through a chitin-induced pathway in wheat. More importantly, silencing TaWAK2A-800 reduced the expression levels of the chitin-triggering immune pathway marker genes TaCERK1, TaRLCK1B, and TaMAPK3 after inoculation with Fg [122]. For the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of WRKYs was a exciter, which promoted the downstream signalings: the activated WRKYs then bind to and regulate the expression of NOX/RBOH genes [107]. Just in time, one study reported that TaWRKY19 repressed plant immunity against pathogens by negatively regulating the transcriptional level of TaNOX10 and compromising ROS generation in wheat [144]. In addition, Köster et al. indicated that Ca2+ signaling was central to both pattern- and effector-triggered immunity activation of the immune system in plants [142]. Furthermore, the calcium-dependent protein kinase TaCDPK can directly interact with NOXs/RBOHs in a Ca2+-dependent manner [139,145,146], both of which are synergistically involved in plant defense responses to pathogens [147–150]. Therefore, under pathogen stimulation, plant cells often elevate the levels of ROS to implement plant immunity by eliminating compromised host cells, in turn limiting the further infection by the pathogen. At the same time, H2O2, the precursor of ROS, plays a crucial role during cell wall rigidification (lignification and crosslinking of cell wall monomers) [151]. On the other hand, plant cells also enhance the expression levels of peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) to scavenge ROS and maintain the redox balance in plant cells.

Figure 4. ROS homeostasis regulated by CERK-mediated immune signaling plays a crucial role during fungus–plant interactions. In this figure, the chitin-induced particles CERK, LysM, CEBiP, BIK1, and ROPs/RACs and GEF-mediated ROS homeostasis by regulation of NOX activity, perhaps perform vital roles in plant response to FHB. In Arabidopsis, a chitin elicitor receptor kinase CERK1, and a LysM-containing receptor-like kinase LYK5 were found to be able to bind chitin and form a chitin-dependent immune complex, CERK1-LYK5 [132,133], in which AtCERK1 is involved in activating BIK1 by phosphorylation directly. The activated BIK1 (GTP-BIK1) directly phosphorylates AtRbohD and enhances ROS production for defense responses [134,135]. In rice, a plasma membrane-localized receptor-like kinase OsCERK1 is associated with receptor-like kinase OsCEBiP under chitin treatment [136]. In addition, OsCEBiP can form a homodimer upon chitin binding that is followed by heterodimerization with OsCERK1, creating a signaling-active sandwich-type receptor system [137,138]. Then, OsGEF1, a regulator functioning as a molecular switch, is phosphorylated by OsCERK1 [139]. The activated OsGEF1, coupling with OsRACK1 [140] in turn, phosphorylates a ROP/RAC GTPase, OsRAC1, and changes it from the inactive form RAC-GDP to the active form RAC-GTP [130,141]. Finally, the actived OsRAC1 then activates OsRbohB (OsNOX1) for ROS production by directly interacting with the N-terminus of NADPH oxidase [142,143]. Additionally, a wall-associated kinases WAK2A-800 performed a positive role in response to Fg through a chitin-induced pathway. More importantly, silencing TaWAK2A-800 reduced the expression levels of the chitin-triggering marker genes TaCERK1, TaRLCK1B, and TaMAPK3 under treatment with Fg [121]. MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of WRKYs was a exciter, which promoted the downstream signalings: the activated WRKYs then bind to and regulate the expression of NOX/RBOH genes [107].For example, TaWRKY19 repressed plant immunity against pathogens by negatively regulating the transcriptional level of TaNOX10 and compromising ROS generation in wheat [144]. In addition, Ca2+ signaling was central to both pattern- and effector-triggered immunity activation of the immune system in plants [142]. Moreover, CDPKs, in a Ca2+-dependent manner, can directly interact with and activate NOXs/RBOHs for ROS production, which plays a crucial role in plant defense responses to pathogens. Therefore, under pathogen stimulation, plant cells often elevate the levels of ROS to implement plant immunity by eliminating compromised host cells, in turn limiting the further infection by the pathogen. At the same time, H2O2, the precursor of ROS, plays a crucial role during cell wall rigidification (lignification and crosslinking of cell wall monomers) [151]. On the other hand, plant cells also enhance the expression levels of peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) to scavenge ROS and maintain the redox balance in plant cells. CERK1: a plasma membrane-localized chitin elicitor receptor kinase 1; LYP4/6: receptor-like OsLYP4 and OsLYP6; CEBiP: receptor-like kinases; LKY5: LysM-containing receptor-like kinase 5; GEF: guanine nucleotide exchange factors; RAC1-GTP: a subfamily of Rho-type GTPases; RACK: receptor for activated C-kinase; CDPK: calcium-dependent protein kinase; BIK1: botrytis-induced kinase 1; PBL1: PBS-like kinase, which is a close homolog of receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases; TF: transcription factor.

Based on these results, CERK1-mediated signaling models were constructed as shown in Figure 4, in which the regulation patterns of NOXs/RBOHs activity and maintenance of intracellular ROS homeostasis during plant response to FHB stress), will offer valuable information for further studies in this field and provide important cues for crop improvement by genetic engineering and molecular breeding during agricultural practices.

5. Biological and Chemical Control

5.1. Biological Control

In recent years, biological control techniques have been widely applied to control plant pathogens. There are many species of microorganism that can be applied in biological control, such as bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes [20,152]. The main mechanisms of biocontrol microorganisms are antagonism, competition, and hyperparasitoidism. At present, a variety of antagonistic strains against Fg have been identified, such as Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas radiobacter, Bacillus thuringiensis, Agrobacterium radiobacillus, Actinomycetes, Burkholderia yabunchirtal, and the endophytic fungus Simplicillium lamellicola [19]. Among them, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus thuringiensis, Pseudomonas radiobacter, and Agrobacterium radiobacter are easy to separate and cultivate; their dormant spores have strong stress resistance and long survival time. Accordingly, they have attracted people’s attention and have been commercialized as preparations, showing great application prospects in biological control [153]. For example, Streptomyces spp. from Streptomyces Aureus have a strong inhibitory effect on wheat FHB [154]. Zhang et al. (2020) found that Streptomyces pratensis strain S10 parasitized wheat roots and inhibited wheat FHB by inhibiting mycelial growth and reducing DON gene expression [155]. Moreover, Frenolicin B, the main active component from fermentation broth of Streptomyces sp. NEAU-H3 showed strong antifungal activity against Fg by affecting mycelia and cell contents [156]. In addition, Bacillus velezensis RC 218 was identified as a biocontrol fungicide against Fg by inducing cell wall thickening and preventing cell plasmolysis and collapse in the host [157]. Another research proposed that Metarhizium anisopliae was a potential biocontrol agent, of which 1% broth filtrate could impede conidial germination of Fg; Metarhizium anisopliae can combat Fg by producing secondary metabolites, which inhibit the fungi, promote wheat growth, and trigger a defense response in plants [158]. Xu et al. (2021) found that Bacillus amyloliquefaciens MQ01 reduced the pathogenicity of Fg by degrading zearalenone (ZEN) and synthesizing chitin-binding protein and Bacillus subtilis protease during antagonism [159]. Recently, a new report suggested that Pantoea agglomerans ZJU23, isolated from the bacterial microbiome of perithecia formed by Fg, could efficiently reduce fungal growth and infection by secreting a key antifungal metabolite, herbicolin A. Herbicolin A can destroy the lipid raft structure and cell membrane integrity by directly binding and disrupting ergosterol-containing lipid rafts, thereby inhibiting the growth, pathogenicity, and toxin synthesis of Fg [160]. In a word, these results illuminate that the mechanism of antagonistic strains against Fg operates mainly through the production of metabolites by inhibiting the growth of Fg mycelium, degrading pathogenic metabolites, and inhibiting toxin gene expression or promoting wheat growth to enhance FHB resistance.

In general, it is difficult for the mycelium to colonize and reproduce rapidly under harsh environmental conditions after germinating from spores. Moreover, the bioactivity of their metabolites is often limited by environmental conditions, which have become a key limiting factor for the development of plant growth-promoting microorganisms resistant to FHB in wheat. Therefore, screening and isolating beneficial microorganisms, unearthing multiple and pivotal FHB-resistance genes, and revealing their resistance mechanisms will help to breed powerful growth-promoting microorganisms by gene recombination technology. In summary, cultivating antagonistic microorganisms with broad-spectrum adaptability and strong resistance to FHB may become a trend in biocontrol studies associated with FHB.

5.2. Chemical Control

To date, there is very limited promising germplasm for wheat blast resistance in production, and chemical spraying during the flowering stage of wheat is the main method of FHB control. It has been demonstrated that the common chemical fungicides, including benzimidazole fungicide carbendazim, sterol demethylase inhibitor (DMI) fungicide tebuconazole, and mimosine are effective against FHB. Among these, carbendazim has a perfect inhibition effect and has been widely applied in agricultural production [161]. However, the single use of the same chemical fungicide over a long period of time inevitably leads to drug resistance of strains [162,163]. Therefore, with progress in research, a new group of antimicrobial fungicides such as cycloheximide, chlorothalonil, and prothioconazole has been studied and reported to cater to the needs of agricultural development. In addition, a chemical material, nanosilver, was confirmed as an inhibitor of the growth of pathogenic microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and mycoplasma; it is also highly lethal to certain viruses and protozoa without drug resistance and can be used as a long-lasting and safe fungistat [164]. Takemoto et al. (2018) found that K20, a novel amphiphilic aminoglycoside fungicide, had a good inhibitory effect on many fungal species, including Fg [165]. Duan et al. (2018) found that epoxiconazole inhibited the production of toxins such as DON by Fg [166]. Zhu et al. (2020) found that vitamin E had an indirect regulatory effect on the accumulation of vomitoxin (DON) in wheat [167]. Moreover, trans-2-hexenal, T2H, a typical green leaf volatile, synthesized from the primary metabolite linolenic acid or linoleic acid in plants, was proved to be a biofumigant for protecting crops against Fg [168]. Therefore, in the absence of resistant germplasm resources in wheat and with the scarcity of FHB-resistant strains with wide adaptability, the choice of chemical fungicides has become a common method of FHB control, but this is inevitably contrary to the concept of “advocating green production mode and promoting sustainable agricultural development”.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

In summary, scientists worldwide have made great progress in FHB-resistance germplasm, genetics, and genomics in recent years, laying a solid foundation for the improvement of FHB-resistance breeding. However, the progress of resistance breeding is relatively slow, which cannot cater to the demand for resistance germplasm resources in agricultural production. The reasons for this are found mainly in the following aspects: (1)although there are abundant FHB-resistance resources worldwide, they have not been studied and utilized widely, due to their narrow genetic base and poor agronomic traits. (2) Although some QTLs/genes for resistance to FHB have been discovered, the number of resistance master genes that have been cloned is limited, and their function and stability have rarely been studied and validated in depth. (3) Research on FHB-resistance mechanisms is mainly at the morphological and physiological levels, and little research is at the molecular level. In addition, important agronomic traits such as wheat yield and quality are complex quantitative traits influenced by multiple genes and environmental interactions. Accordingly, it is difficult to cater to food security and needs for a better life by relying solely on conventional breeding techniques. Therefore, it is imperative to accelerate research on wheat genomic and molecular genetic breeding. Screening for more and better resistance master genes, mapping their fine genetic profiles, and evaluating their practical application are the urgent tasks for us now.

References

- Covarelli, L.; Beccari, G.; Prodi, A.; Generotti, S.; Etruschi, F.; Juan, C.; Ferrer, E.; Mañes, J. Fusarium Species, chemotype characterization and trichothecene contamination of durum and soft wheat in an area of central Italy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 540–551.

- He, X.Y.; Dreisigacker, S.; Singh, R.P.; Singh, P.K. Genetics for low correlation between fusarium head blight disease and deoxynivalenol (DON) content in a bread wheat mapping population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 2401–2411.

- Ma, Z.Q.; Xie, Q.; Li, G.Q.; Jia, H.Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Kong, Z.X.; Li, N.; Yuan, Y. Germplasms, genetics and genomics for better control of disastrous wheat fusarium head blight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1541–1568.

- Brisco, E.I.; Brown, L.K.; Olson, E.L. Fusarium head blight resistance in Aegilops Tauschii. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2017, 64, 2049–2058.

- Zhang, A.M.; Yang, W.L.; Li, X.; Sun, J.Z. Current status and perspective on research against fusarium head blight in wheat. Hereditas 2018, 40, 858–873.

- Bai, G.H.; Shaner, G.E. Variation in Fusarium graminearum and cultivar resistance to wheat scab. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 975–979.

- Frohberg, R.C.; Stack, R.W.; Olson, T.; Miller, J.D.; Megoum, M. Registration of ‘Alsen’ Wheat. Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 2311–2312.

- Nishio, Z.; Takata, K.; Tabiki, T.; Ito, M.; Takenaka, S.; Kuwabara, T.; Iriki, N.; Ban, T. Diversity of resistance to fusarium head blight in japanese winter wheat. Breed. Sci. 2004, 54, 79–84.

- Badea, A.; Eudes, F.; Graf, R.J.; Laroche, A.; Gaudet, D.A.; Sadasivaiah, R.S. Phenotypic and marker-assisted evaluation of spring and winter wheat germplasm for resistance to fusarium head blight. Euphytica 2008, 164, 803–819.

- Bai, G.H.; Su, Z.Q.; Cai, J. Wheat resiatance to fusarium head blight. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 40, 336–346.

- Bluhm, B.H.; Zhao, X.; Flaherty, J.E.; Xu, J.R.; Dunkle, L.D. RAS2 regulates growth and pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 627–636.

- Jia, L.J.; Tang, H.Y.; Wang, W.Q.; Yuan, T.L.; Wei, W.Q.; Pang, B.; Gong, X.M.; Wang, S.F.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, D.; et al. A linear nonribosomal octapeptide from Fusarium graminearum facilitates cell-to-cell invasion of wheat. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–20.

- Palacios, S.A.; Canto, A.D.; Erazo, J.; Torres, A.M. Fusarium cerealis causing fusarium head blight of durum wheat and its associated mycotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 346, 109161.

- Tang, L.; Chi, H.W.; Li, W.D.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Chen, L.; Zou, S.S.; Liu, H.X.; Liang, Y.C.; Yu, J.F.; et al. FgPsd2, a phosphatidylserine decarboxylase of Fusarium graminearum, regulates development and virulence. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2021, 146, 103483.

- Ding, Y.; Gardiner, D.M.; Kazan, K. Transcriptome analysis reveals infection strategies employed by Fusarium graminearum as a root pathogen. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 256, 126951.

- Spanic, V.; Cosic, J.; Zdunic, Z.; Drezner, G. Characterization of agronomical and quality traits of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) for fusarium head blight pressure in different environments. Agronomy 2021, 11, 213.

- Drakopoulos, D.; Kgi, A.; Six, J.; Zorn, A.; Vogelgsang, S. The agronomic and economic viability of innovative cropping systems to reduce fusarium head blight and related mycotoxins in wheat. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103198.

- Senatore, M.T.; Ward, T.J.; Cappelletti, E.; Beccari, G.; Prodi, A. Species diversity and mycotoxin production by members of the fusarium tricinctum species complex associated with fusarium head blight of wheat and barley in Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 358, 109298.

- Abaya, A.; Serajazari, M.; Hsiang, T. Control of fusarium head blight using the endophytic fungus, Simplicillium lamellicola, and its effect on the growth of Triticum aestivum. Biol. Control 2021, 160, 104684.

- Pellan, L.; Dieye, C.A.T.; Durand, N.; Fontana, A.; Schorr-Galindo, S.; Strub, C. Biocontrol agents reduce progression and mycotoxin production of Fusarium graminearum in spikelets and straws of wheat. Toxins 2021, 13, 597.

- Goncharov, A.A.; Gorbatova, A.S.; Sidorova, A.A.; Tiunov, A.V.; Bocharov, G.A. Mathematical modelling of the interaction of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and fusarium species (Fusarium spp.). Ecol. Model. 2022, 465, 109856.

- Li, T.; Bai, G.H.; Wu, S.Y.; Gu, S.L. Quantitative trait loci for resistance to fusarium head blight in the chinese wheat landrace Huangfangzhu. Euphytica 2012, 185, 93–102.

- Zhang, X.H.; Pan, H.Y.; Bai, G.H. Quantitative trait loci responsible for fusarium head blight resistance in chinese landrace baishanyuehuang. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 125, 495–502.

- Cai, J.; Bai, G.H. Quantitative trait loci for fusarium head blight resistance in Huangcandou× ‘jagger’ wheat population. Crop Sci. 2014, 54, 2520–2528.

- Chen, S.L.; Zhang, Z.L.; Sun, Y.Y.; Li, D.S.; Gao, D.R.; Zhan, K.H.; Cheng, S.H. Identification of quantitative trait loci for fusarium head blight (FHB) resistance in the cross between wheat landrace N553 and elite cultivar Yangmai 13. Mol. Breed. 2021, 41, 1–13.

- Lin, F.; Xue, Z.Z.; Zhang, C.Q.; Zhang, Z.K.; Kong, G.Q.; Yao, D.G.; Tian, D.G.; Zhu, H.L.; Li, C.J.; Cao, Y.; et al. Mapping QTL Associated with resistance to fusarium head blight in the Nanda2419×Wangshuibai population. II: Type I resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 112, 528–535.

- Lu, W.Z.; Cheng, S.H.; Wang, Y.Z. Study on Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat, 1st ed.; Science Press: Peking, China, 2001; pp. 3–12. Available online: https://book.sciencereading.cn/shop/book/Booksimple/onlineRead.do?id=B2B4195C7F400419F83C82EA84B62B57C000&readMark=0 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Lewandowski, S.M.; Bushnell, W.R.; Evans, C.K. Distribution of mycelial colonies and lesions in field-grown barley inoculated with Fusarium graminearum. Phytopathology 2006, 96, 567–581.

- Wanjiru, W.M.; Kang, Z.S.; Buchenauer, H. Importance of cell wall degrading enzymes produced by Fusarium graminearum during infection of wheat heads. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 108, 803–810.

- Xu, Y.A.; Hideki, N. The infection process of wheat SCAB pathogen. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 1989, 12, 33–38.

- Liu, P.; Zhang, X.X.; Zhang, F.; Xu, M.Z.; Ye, Z.X.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; Han, X.L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhong, K.L.; et al. Virus-derived SiRNA activates plant immunity by interfering with ROS scavenging. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1088–1103.

- Wu, B.Y.; Li, P.; Hong, X.F.; Xu, C.H.; Wang, R.; Liang, Y. The receptor-like cytosolic kinase RIPK activates NADP-malic enzyme 2 to generate NADPH for fueling the ROS production. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 887–903.

- Hao, G.X.; Helene, T.; Susan, M. Chitin triggers tissue-specific immunity in wheat associated with fusarium head blight. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 832502.

- Strange, R.N.; Smith, H. Specificity of choline and betaine as stimalants of Fusarium graminearum. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1978, 70, 187–192.

- Strange, R.N.; Deramo, A.; Smith, H. Virulence Enhancement of Fusarium graminearum by chloline and betaine and of Botrytis Cinerea by other constituents of wheat germ. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1978, 70, 201–207.

- Walter, S.; Nicholson, P.; Doohan, F.M. Action and reaction of host and pathogen during fusarium head blight disease. New Phytol. 2010, 185, 54–66.

- Ding, S.; Mehrabi, R.; Koten, C.; Kang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Seong, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Xu, J.R. Transducin beta-like gene FTL1 is essential for pathogenesis in Fusarium graminearum. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 867–876.

- Yu, H.Y.; Seo, J.A.; Kim, J.E.; Han, K.H.; Shim, W.B.; Yun, S.H.; Lee, Y.W. Functional analyses of heterotrimeric G protein Gα and Gβ subunits in Gibberella zeae. Microbilogy 2008, 154, 392–401.

- Sridhar, P.S.; Trofimova, D.; Subramaniam, R.; Fundora, D.G.P.; Foroud, N.A.; Allingham1, J.S.; Loewen, M.C. Ste2 receptor-mediated chemotropism of Fusarium graminearum contributes to its pathogenicity against wheat. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10770.

- Chong, X.F.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liang, Y.C.; Chen, L.; Zou, S.S.; Dong, H.S. The dynamin-like GTPase FgSey1 plays a critical role in fungal development and virulence in Fusarium graminearum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02720-19.

- Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.D.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liang, Y.C.; Chen, L.; Zou, S.S.; Dong, H.S. The ADP-ribosylation Factor-like small GTPase FgArl1 participates in growth, pathogenicity and DON production in Fusarium graminearum. Fungal Biol. 2020, 124, 969–980.

- Yang, C.D.; Li, J.J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.Z.; Liao, D.H.; Yun, Y.Z.; Zheng, W.H.; Abubakar, Y.S.; Li, G.P.; Wang, Z.H.; et al. FgVps9, a Rab5 GEF, is critical for DON biosynthesis and pathogenicity in Fusarium graminearum. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1714.

- Zhang, C.Q.; Ren, X.X.; Wang, X.T.; Wan, Q.; Ding, K.J.; Chen, L. FgRad50 regulates fungal development, pathogenicity, cell wall integrity and the DNA damage response in Fusarium graminearum. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 2970.

- Zhang, Y.M.; Dai, Y.F.; Huang, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, P.; Xu, H.F.; Xu, J.R.; Liu, H.Q. The SR-protein FgSrp2 regulates vegetative growth, sexual reproduction and pre-mRNA processing by interacting with FgSrp1 in Fusarium graminearum. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 607–619.

- Gao, T.; He, D.; Liu, X.; Ji, F.; Xu, J.H.; Shi, J.R. The pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2 (PDK2) is associated with conidiation, mycelial growth, and pathogenicity in Fusarium graminearum. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2020, 2, 11.

- Adnan, M.; Fang, W.Q.; Sun, P.; Zheng, Y.L.; Abubakar, Y.S.; Zhang, J.; Lou, Y.; Zheng, W.H.; Lu, G.D. R-SNARE FgSec22 is essential for growth, pathogenicity and DON production of Fusarium graminearum. Curr. Genet. 2020, 66, 421–435.

- Sun, M.L.; Bian, Z.Y.; Luan, Q.Q.; Chen, Y.T.; Wang, W.; Dong, Y.R.; Chen, L.F.; Hao, C.F.; Xu, J.R.; Liu, H.Q. Stage-specific regulation of purine metabolism during infectious growth and sexual reproduction in Fusarium graminearum. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 757–773.