Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a highly heterogeneous inflammatory disease regarding both its pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. However, it is treated according to the “one-size-fits-all” approach, which may restrict response to treatment. Thus, there is an unmet need for the stratification of patients with AD into distinct endotypes and clinical phenotypes based on biomarkers that will contribute to the development of precision medicine in AD. The development of reliable biomarkers that may distinguish which patients with AD are most likely to benefit from specific targeted therapies is a complex procedure and to date none of the identified candidate biomarkers for AD has been validated for use in routine clinical practice. Reliable biomarkers in AD are expected to improve diagnosis, evaluate disease severity, predict the course of disease, the development of comorbidities, or the therapeutic response, resulting in effective and personalized treatment of AD.

- atopic dermatitis

- biomarkers

- precision medicine

- personalized treatment

- TARC/CCL17

- MDC/CCL22

- CTACK/CCL27

- periostin

- IL-13

- IL-22

1. Introduction

2. Definition and Subtypes of Biomarkers

To date, there are available several, although overlapping, definitions of the term biomarker. A biomarker or biological marker is defined as a “characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention”, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [14]. Another definition of biomarker proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) is as follows: “any substance, structure or process that can be measured in the body or its products and influence or predict the incidence of outcome or disease. Biomarkers can be classified into markers of exposure, effect, and susceptibility” [15]. Since biomarkers are widely used in the process of drug discovery, development and approval, the initial definition of NIH has evolved into a broader, enriched definition of biomarker adopted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) namely: “a defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention, including therapeutic interventions. Molecular, histologic, radiographic, or physiologic characteristics are types of biomarkers. A biomarker is not an assessment of how a patient feels, functions, or survives” [16]. Moreover, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) defines a biomarker more restrictively as ‘‘a biological molecule found in blood, other body fluids, or tissues that can be used to follow body processes and diseases in humans and animals’’ [17]. The biologic origin of a biomarker could be genomic information, transcriptomic profiles obtained by analysis of mRNA and miRNA, proteins such as cytokines and other mediators from body fluids (whole blood, serum, plasma, tissue fluids) or tape stripping, and morphological information [18]. Regarding the purpose/value of biomarkers, there are seven different categories as defined by the FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group: susceptibility/risk, diagnostic, monitoring/severity, prognostic, predictive, pharmacodynamic/response, and safety [16]. Thus, evaluation of all these subtypes of biomarkers could play a significant role in the diagnosis, prognosis, management, and treatment of AD.3. Biomarkers in AD

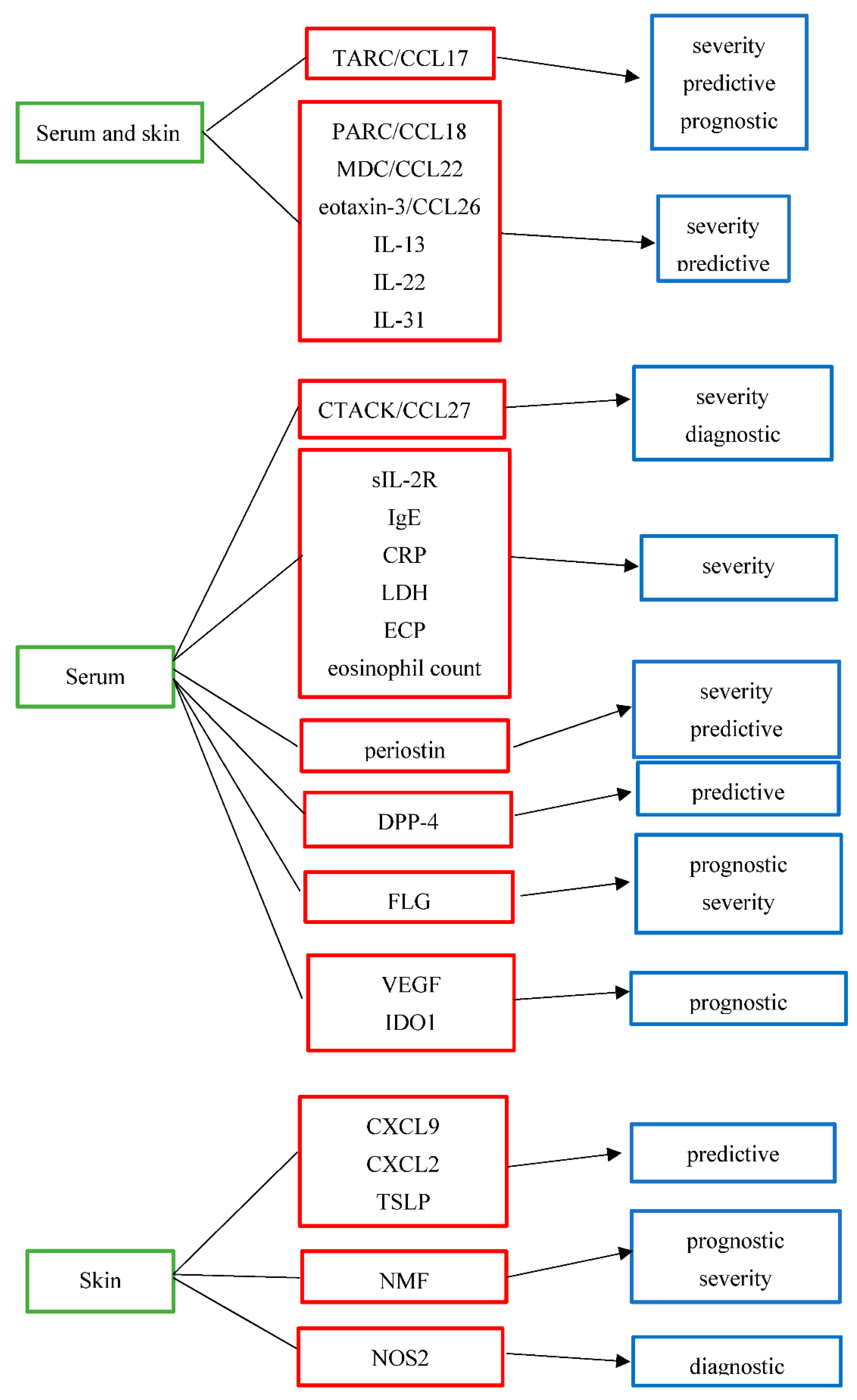

Clinical research has discovered several different subtypes of potential biomarkers in AD. However, to date none of these candidate biomarkers are used in routine clinical practice, since they have not yet reached the status of validation and qualification [19]. Recently, an international panel of experts consented that the most important performance elements for high-quality AD biomarkers are reliability, clinical validity, relevance, and high positive predictive value. Regarding the purpose of biomarkers in AD, the prediction of therapeutic response and disease progression was considered the most important. Additionally, insufficient validation by independent researchers was reported as a major obstacle to the transfer of AD biomarkers in clinical practice. All experts identified validation and further studies as a high-priority research objective [2]. Most of the skin biomarkers in AD have been identified using whole-tissue skin biopsy for sample retrieval, an invasive approach that is not always feasible, especially in the pediatric population. Consequently, less invasive sampling methods have been recently developed for AD biomarker assessment, such as the use of tape strips [20[20][21][22][23],21,22,23], dried blood spots [24], patients’ serum [25], or saliva [26]. Candidate AD biomarkers can be divided into different subtypes according to their suggested use. The candidate biomarkers for AD and their suggested use are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Biomarker | Full Name | Purpose | Grade of Evidence | Biologic Origin | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[25,27,28,29,30,32,13][33,25][34,2735,36,][28][29][30][31]37,[38,40,32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40] |

thymus and activation-regulated chemokine/ | C-C motif ligand 17 | severity | predictive | prognostic | high | moderate | low | serum and skin | |||||||||||||||

pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine/C-C motif ligand 18 | severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum and skin | |||||||||||||||||||

MDC/CCL22 [13,25,27,28,29,30,76] | macrophage-derived chemokine/C-C motif ligand 22 | severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum and skin | ||||||||||||||||||

eosinophil-attracting chemokine/C-C motif ligand 26 | severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum and skin | |||||||||||||||||||

IL-13 | interleukin-13 | severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum and skin | ||||||||||||||||||

IL-22 | interleukin-22 | severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum and skin | ||||||||||||||||||

IL-31 [13,52,53,[47]54,[48]55,[49]56,[50]57,58] | interleukin-31 | severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum and skin | ||||||||||||||||||

[1333,][2534,]82,83,[27][32][33][53][54]84[55] |

cutaneous T-cell-attracting chemokine/ | C-C motif ligand 27 | severity | diagnostic/differential diagnosis from psoriasis | moderate | low | serum | |||||||||||||||||

sIL-2R | soluble IL-2 receptor | severity | moderate | serum | ||||||||||||||||||||

immunoglobulin E | severity | moderate | serum | |||||||||||||||||||||

CRP [39] | [59] |

C-reactive protein | severity | low | serum | |||||||||||||||||||

LDH | lactate dehydrogenase | severity | moderate | serum | ||||||||||||||||||||

ECP | eosinophil cationic protein | severity | moderate | serum | ||||||||||||||||||||

Eosinophil count [40,41,43,44] | severity | moderate | serum | |||||||||||||||||||||

severity | predictive | moderate | low | serum | ||||||||||||||||||||

DPP-4 [9] | dipeptidyl peptidase-4 | predictive | low | serum | ||||||||||||||||||||

CXCL9 [76] | [41] |

C-X-C motif ligand 9 | predictive | low | skin | |||||||||||||||||||

CXCL2 [76] | [41] |

C-X-C motif ligand 2 | predictive | low | skin | |||||||||||||||||||

TSLP [70] | [66] |

thymic stromal lymphopoietin protein | predictive | moderate | skin | |||||||||||||||||||

NMF | natural moisturizing factor | prognostic | severity | moderate | low | skin | ||||||||||||||||||

filaggrin | prognostic | severity | moderate | low | serum | |||||||||||||||||||

VEGF [73] | [74] |

vascular endothelial growth factor | prognostic | low | serum | |||||||||||||||||||

IDO1 [74] | [75] |

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 | prognostic for eczema herpeticum | low | serum | |||||||||||||||||||

NOS2 | nitric oxide synthase 2 | diagnostic/differential diagnosis from psoriasis | low | skin |

References

- Eichenfield, L.F.; Tom, W.L.; Chamlin, S.L.; Feldman, S.R.; Hanifin, J.M.; Simpson, E.L.; Berger, T.G.; Bergman, J.N.; Cohen, D.E.; Cooper, K.D.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 338–351.

- Ziehfreund, S.; Tizek, L.; Hangel, N.; Fritzsche, M.; Weidinger, S.; Smith, C.; Bryce, P.; Greco, D.; Bogaard, E.; Flohr, C.; et al. Requirements and expectations of high-quality biomarkers for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis in 2021—A two-round Delphi survey among international experts. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022; Online ahead of print.

- Moyle, M.; Cevikbas, F.; Harden, J.L.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Understanding the immune landscape in atopic dermatitis: The era of biologics and emerging therapeutic approaches. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 756–768.

- Werfel, T.; Allam, J.-P.; Biedermann, T.; Eyerich, K.; Gilles, S.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Hoetzenecker, W.; Knol, E.; Simon, H.-U.; Wollenberg, A.; et al. Cellular and molecular immunologic mechanisms in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 336–349.

- Bakker, D.S.; Nierkens, S.; Knol, E.F.; Giovannone, B.; Delemarre, E.M.; van der Schaft, J.; van Wijk, F.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Drylewicz, J.; Thijs, J.L. Confirmation of multiple endotypes in atopic dermatitis based on serum biomarkers. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 189–198.

- Brunner, P.M.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Leung, D.Y. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad-spectrum and targeted therapies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, S65–S76.

- Mansouri, Y.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Immune Pathways in Atopic Dermatitis, and Definition of Biomarkers through Broad and Targeted Therapeutics. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 858–873.

- Bieber, T.; D’Erme, A.M.; Akdis, C.A.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Lauener, R.; Schäppi, G.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P. Clinical phenotypes and endophenotypes of atopic dermatitis: Where are we, and where should we go? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, S58–S64.

- Wollenberg, A.; Howell, M.D.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Silverberg, J.I.; Kell, C.; Ranade, K.; Moate, R.; van der Merwe, R. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with tralokinumab, an anti–IL-13 mAb. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 135–141.

- Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Su, H.; Wen, H.; Li, W.; Yao, X. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for the treatment of adult atopic dermatitis: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 888–891.e6.

- Simpson, E.L.; Flohr, C.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Bieber, T.; Sofen, H.; Taïeb, A.; Owen, R.; Putnam, W.; Castro, M.; DeBusk, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab (an anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody) in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical corticosteroids: A randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial (TREBLE). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 863–871.e11.

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Silverberg, J.I.; Nemoto, O.; Forman, S.B.; Wilke, A.; Prescilla, R.; de la Peña, A.; Nunes, F.P.; Janes, J.; Gamalo, M.; et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 913–921.e9.

- Thijs, J.; Krastev, T.; Weidinger, S.; Buckens, C.F.; De Bruin-Weller, M.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.; Flohr, C.; Hijnen, D. Biomarkers for atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 15, 453–460.

- Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95.

- WHO International Programme on Chemical Safety Biomarkers in Risk Assessment: Validity and Validation. 2001. Available online: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc222.htm (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- FDA-NIH Biomarker Working Group. BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and Other Tools) Resource. 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326791/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- EMA. Glossary: Biomarker. 2020. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary/biomarker (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Renert-Yuval, Y.; Thyssen, J.P.; Bissonnette, R.; Bieber, T.; Kabashima, K.; Hijnen, D.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Biomarkers in atopic dermatitis—a review on behalf of the International Eczema Council. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1174–1190.e1.

- Gromova, M.; Vaggelas, A.; Dallmann, G.; Seimetz, D. Biomarkers: Opportunities and Challenges for Drug Development in the Current Regulatory Landscape. Biomark. Insights 2020, 15, 1177271920974652.

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Diaz, A.; Pavel, A.B.; Fernandes, M.; Lefferdink, R.; Erickson, T.; Canter, T.; Rangel, S.; Peng, X.; Li, R.; et al. Use of Tape Strips to Detect Immune and Barrier Abnormalities in the Skin of Children With Early-Onset Atopic Dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 1358–1370.

- Castelo-Soccio, L. Stripping Away Barriers to Find Relevant Skin Biomarkers for Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 1342.

- Pavel, A.B.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Wu, J.; Del Duca, E.; Diaz, A.; Lefferdink, R.; Fang, M.M.; Canter, T.; Rangel, S.M.; Zhang, N.; et al. Tape strips from early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis highlight disease abnormalities in nonlesional skin. Allergy 2020, 76, 314–325.

- Kim, B.E.; Goleva, E.; Kim, P.S.; Norquest, K.; Bronchick, C.; Taylor, P.; Leung, D.Y. Side-by-Side Comparison of Skin Biopsies and Skin Tape Stripping Highlights Abnormal Stratum Corneum in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 2387–2389.e1.

- Thijs, J.L.; Fiechter, R.; Giovannone, B.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Knol, E.F.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A.F.M.; Drylewicz, J.; Nierkens, S.; Hijnen, D. Biomarkers detected in dried blood spots from atopic dermatitis patients strongly correlate with disease severity. Allergy 2019, 74, 2240–2243.

- Ungar, B.; Garcet, S.; Gonzalez, J.; Dhingra, N.; da Rosa, J.C.; Shemer, A.; Krueger, J.G.; Suarez-Farinas, M.; Guttman-Yassky, E. An Integrated Model of Atopic Dermatitis Biomarkers Highlights the Systemic Nature of the Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 603–613.

- Thijs, J.L.; Van Seggelen, W.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.; De Bruin-Weller, M.; Hijnen, D. New Developments in Biomarkers for Atopic Dermatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 479–487.

- He, H.; Del Duca, E.; Diaz, A.; Kim, H.J.; Gay-Mimbrera, J.; Zhang, N.; Wu, J.; Beaziz, J.; Estrada, Y.; Krueger, J.G.; et al. Mild atopic dermatitis lacks systemic inflammation and shows reduced nonlesional skin abnormalities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1369–1380.

- Thijs, J.L.; Nierkens, S.; Herath, A.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A.; Knol, E.; Giovannone, B.; De Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Hijnen, D. A panel of biomarkers for disease severity in atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 698–701.

- Thijs, J.L.; Drylewicz, J.; Fiechter, R.; Strickland, I.; Sleeman, M.A.; Herath, A.; May, R.D.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A.; Knol, E.F.; Giovannone, B.; et al. EASI p-EASI: Utilizing a combination of serum biomarkers offers an objective measurement tool for disease severity in atopic dermatitis patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 1703–1705.

- Hulshof, L.; Overbeek, S.A.; Wyllie, A.L.; Chu, M.L.J.N.; Bogaert, D.; De Jager, W.; Knippels, L.M.J.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Van Aalderen, W.M.C.; Garssen, J.; et al. Exploring Immune Development in Infants With Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis. Front Immunol. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 630.

- Song, T.W.; Sohn, M.H.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, K.-E. Increased serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine and cutaneous T cell-attracting chemokine levels in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2006, 36, 346–351.

- Hijnen, D.; De Bruin-Weller, M.; Oosting, B.; Lebre, C.; De Jong, E.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.; Knol, E. Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) and cutaneous T cell–attracting chemokine (CTACK) levels in allergic diseases: TARC and CTACK are disease-specific markers for atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 334–340.

- Machura, E.; Rusek-Zychma, M.; Jachimowicz, M.; Wrzask, M.; Mazur, B.; Kasperska-Zajac, A. Serum TARC and CTACK concentrations in children with atopic dermatitis, allergic asthma, and urticaria. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 23, 278–284.

- Ahrens, B.; Schulz, G.; Bellach, J.; Niggemann, B.; Beyer, K. Chemokine levels in serum of children with atopic dermatitis with regard to severity and sensitization status. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2015, 26, 634–640.

- Fujisawa, T.; Nagao, M.; Hiraguchi, Y.; Katsumata, H.; Nishimori, H.; Iguchi, K.; Kato, Y.; Higashiura, M.; Ogawauchi, I.; Tamaki, K. Serum measurement of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine/CCL17 in children with atopic dermatitis: Elevated normal levels in infancy and age-specific analysis in atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 20, 633–641.

- Landheer, J.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Boonacker, C.; Hijnen, D.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.; Röckmann, H. Utility of serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine as a biomarker for monitoring of atopic dermatitis severity. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 1160–1166.

- Yasukochi, Y.; Nakahara, T.; Abe, T.; Kido-Nakahara, M.; Kohda, F.; Takeuchi, S.; Hagihara, A.; Furue, M. Reduction of serum TARC levels in atopic dermatitis by topical anti-inflammatory treatments. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 32, 240–245.

- Kou, K.; Aihara, M.; Matsunaga, T.; Chen, H.; Taguri, M.; Morita, S.; Fujita, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kambara, T.; Ikezawa, Z. Association of serum interleukin-18 and other biomarkers with disease severity in adults with atopic dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2012, 304, 305–312.

- Kyoya, M.; Kawakami, T.; Soma, Y. Serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) and interleukin-31 levels as biomarkers for monitoring in adult atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 75, 204–207.

- Miyahara, H.; Okazaki, N.; Nagakura, T.; Korematsu, S.; Izumi, T. Elevated umbilical cord serum TARC/CCL17 levels predict the development of atopic dermatitis in infancy. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 186–191.

- Glickman, J.W.; Han, J.; Garcet, S.; Krueger, J.G.; Pavel, A.B.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Improving evaluation of drugs in atopic dermatitis by combining clinical and molecular measures. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 3622–3625.e19.

- Esaki, H.; Brunner, P.M.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Czarnowicki, T.; Huynh, T.; Tran, G.; Lyon, S.; Rodriguez, G.; Immaneni, S.; Johnson, D.B.; et al. Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is T H 2 but also T H 17 polarized in skin. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 1639–1651.

- Czarnowicki, T.; Esaki, H.; Gonzalez, J.; Malajian, D.; Shemer, A.; Noda, S.; Talasila, S.; Berry, A.; Gray, J.; Becker, L.; et al. Early pediatric atopic dermatitis shows only a cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA)+ TH2/TH1 cell imbalance, whereas adults acquire CLA+ TH22/TC22 cell subsets. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 941–951.e3.

- Noda, S.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Ungar, B.; Kim, S.J.; de Guzman Strong, C.; Xu, H.; Peng, X.; Estrada, Y.D.; Nakajima, S.; Honda, T.; et al. The Asian atopic dermatitis phenotype combines features of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with increased TH17 polarization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 1254–1264.

- Nomura, T.; Wu, J.; Kabashima, K.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Endophenotypic Variations of Atopic Dermatitis by Age, Race, and Ethnicity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1840–1852.

- Brunner, P.M.; Pavel, A.B.; Khattri, S.; Leonard, A.; Malik, K.; Rose, S.; On, S.J.; Vekaria, A.S.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Singer, G.K.; et al. Baseline IL-22 expression in patients with atopic dermatitis stratifies tissue responses to fezakinumab. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 143, 142–154.

- Furue, M.; Yamamura, K.; Kido-Nakahara, M.; Nakahara, T.; Fukui, Y. Emerging role of interleukin-31 and interleukin-31 receptor in pruritus in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2018, 73, 29–36.

- Raap, U.; Weißmantel, S.; Gehring, M.; Eisenberg, A.M.; Kapp, A.; Fölster-Holst, R. IL-31 significantly correlates with disease activity and Th2 cytokine levels in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 23, 285–288.

- Neis, M.M.; Peters, B.; Dreuw, A.; Wenzel, J.; Bieber, T.; Mauch, C.; Krieg, T.; Stanzel, S.; Heinrich, P.C.; Merk, H.F. Enhanced expression levels of IL-31 correlate with IL-4 and IL-13 in atopic and allergic contact dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 930–937.

- Raap, U.; Wichmann, K.; Bruder, M.; Ständer, S.; Wedi, B.; Kapp, A.; Werfel, T. Correlation of IL-31 serum levels with severity of atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 122, 421–423.

- Nygaard, U.; Hvid, M.; Johansen, C.; Buchner, M.; Fölster-Holst, R.; Deleuran, M.; Vestergaard, C. TSLP, IL-31, IL-33 and sST2 are new biomarkers in endophenotypic profiling of adult and childhood atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 1930–1938.

- Ozceker, D.; Bulut, M.; Ozbay, A.C.; Dilek, F.; Koser, M.; Tamay, Z.; Guler, N. Assessment of IL-31 levels and disease severity in children with atopic dermatitis. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2018, 46, 322–325.

- Quaranta, M.; Knapp, B.; Garzorz, N.; Mattii, M.; Pullabhatla, V.; Pennino, D.; Andres, C.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Cavani, A.; Theis, F.J.; et al. Intraindividual genome expression analysis reveals a specific molecular signature of psoriasis and eczema. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 244ra90.

- Garzorz-Stark, N.; Krause, L.; Lauffer, F.; Atenhan, A.; Thomas, J.; Stark, S.P.; Franz, R.; Weidinger, S.; Balato, A.; Mueller, N.S.; et al. A novel molecular disease classifier for psoriasis and eczema. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 25, 767–774.

- He, H.; Bissonnette, R.; Wu, J.; Diaz, A.; Proulx, E.S.-C.; Maari, C.; Jack, C.; Louis, M.; Estrada, Y.; Krueger, J.G.; et al. Tape strips detect distinct immune and barrier profiles in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 199–212.

- Morishima, Y.; Kawashima, H.; Takekuma, K.; Hoshika, A. Changes in serum lactate dehydrogenase activity in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr. Int. 2010, 52, 171–174.

- Thijs, J.L.; Knipping, K.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A.F.; Garssen, J.; De Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Hijnen, D.J. Immunoglobulin free light chains in adult atopic dermatitis patients do not correlate with disease severity. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2016, 6, 44.

- Aral, M.; Arican, O.; Gül, M.; Sasmaz, S.; Kocturk, S.A.; Kastal, U.; Ekerbicer, H.C. The relationship between serum levels of total IgE, IL-18, IL-12, IFN-gamma and disease severity in children with atopic dermatitis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2006, 2006, 73098.

- Vekaria, A.S.; Brunner, P.M.; Aleisa, A.I.; Bonomo, L.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Israel, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients show increases in serum C-reactive protein levels, correlating with skin disease activity. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1712.

- Czech, W.; Krutmann, J.; Schopf, E.; Kapp, A. Serum eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) is a sensitive measure for disease activity in atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1992, 126, 351–355.

- Kägi, M.K.; Joller-Jemelka, H.; Wüthrich, B. Correlation of Eosinophils, Eosinophil Cationic Protein and Soluble lnterleukin-2 Receptor with the Clinical Activity of Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology 1992, 185, 88–92.

- Kou, K.; Okawa, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ono, J.; Inoue, Y.; Kohno, M.; Matsukura, S.; Kambara, T.; Ohta, S.; Izuhara, K.; et al. Periostin levels correlate with disease severity and chronicity in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 171, 283–291.

- Masuoka, M.; Shiraishi, H.; Ohta, S.; Suzuki, S.; Arima, K.; Aoki, S.; Toda, S.; Inagaki, N.; Kurihara, Y.; Hayashida, S.; et al. Periostin promotes chronic allergic inflammation in response to Th2 cytokines. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2590–2600.

- Yamaguchi, Y. Periostin in skin tissue and skin-related diseases. Allergol. Int. 2014, 63, 161–170.

- Sung, M.; Lee, K.S.; Ha, E.G.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, M.A.; Lee, S.W.; Jee, H.M.; Sheen, Y.H.; Jung, Y.H.; Han, M.Y. An association of periostin levels with the severity and chronicity of atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 28, 543–550.

- Kim, J.; Kim, B.E.; Lee, J.; Han, Y.; Jun, H.-Y.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.; Leung, D.Y.; Ahn, K. Epidermal thymic stromal lymphopoietin predicts the development of atopic dermatitis during infancy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1282–1285.e4.

- Kezic, S.; O’Regan, G.M.; Lutter, R.; Jakasa, I.; Koster, E.S.; Saunders, S.; Caspers, P.; Kemperman, P.M.; Puppels, G.J.; Sandilands, A.; et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with enhanced expression of IL-1 cytokines in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic dermatitis and in a murine model of filaggrin deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 1031–1039.e1.

- Ní Chaoimh, C.; Nico, C.; Puppels, G.J.; Caspers, P.J.; Wong, X.F.C.C.; Common, J.E.; Irvine, A.D.; Hourihane, J.O. In vivo Raman spectroscopy discriminates between FLG loss-of-function carriers vs. wild-type in day 1-4 neonates. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 500–504.

- Thijs, J.L.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Hijnen, D. Current and Future Biomarkers in Atopic Dermatitis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2017, 37, 51–61.

- Paternoster, L.; Standl, M.; Waage, J.; Baurecht, H.; Hotze, M.; Strachan, D.P.; Curtin, J.A.; Bønnelykke, K.; Tian, C.; Takahashi, A.; et al. Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of 21,000 cases and 95,000 controls identifies new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1449–1456.

- Barker, J.N.; Palmer, C.N.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, H.; Hull, P.R.; Lee, S.P.; Allen, M.H.; Meggitt, S.J.; Reynolds, N.J.; Trembath, R.C.; et al. Null Mutations in the Filaggrin Gene (FLG) Determine Major Susceptibility to Early-Onset Atopic Dermatitis that Persists into Adulthood. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 564–567.

- Tham, E.H.; Leung, D.Y. Mechanisms by Which Atopic Dermatitis Predisposes to Food Allergy and the Atopic March. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2019, 11, 4–15.

- Leung, D.Y.M.; Calatroni, A.; Zaramela, L.S.; LeBeau, P.K.; Dyjack, N.; Brar, K.; David, G.; Johnson, K.; Leung, S.; Ramirez-Gama, M.; et al. The nonlesional skin surface distinguishes atopic dermatitis with food allergy as a unique endotype. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav2685.

- Lauffer, F.; Baghin, V.; Standl, M.; Stark, S.P.; Jargosch, M.; Wehrle, J.; Thomas, J.; Schmidt-Weber, C.B.; Biedermann, T.; Eyerich, S.; et al. Predicting persistence of atopic dermatitis in children using clinical attributes and serum proteins. Allergy 2021, 76, 1158–1172.

- Staudacher, A.; Hinz, T.; Novak, N.; Von Bubnoff, D.; Bieber, T. Exaggerated IDO1 expression and activity in Langerhans cells from patients with atopic dermatitis upon viral stimulation: A potential predictive biomarker for high risk of Eczema herpeticum. Allergy 2015, 70, 1432–1439.