Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Tracy Anthony and Version 2 by Peter Tang.

Dietary sulfur amino acid restriction, also referred to as methionine restriction, increases food intake and energy expenditure and alters body composition in rodents, resulting in improved metabolic health and a longer lifespan. Among the known nutrient-responsive signaling pathways, the evolutionary conserved integrated stress response (ISR) is a lesser-understood candidate in mediating the hormetic effects of dietary sulfur amino acid restriction (SAAR).

- fibroblast growth factor 21

- cystathionine gamma lyase

- healthspan

- liver

- dietary restriction

- amino acid stress

1. Sulfur Amino Acid Restriction as a Dietary Strategy to Promote Leanness and Longevity

Understanding how dietary protein quantity versus quality impacts growth and health has been studied and debated for over 100 years [1][2][1,2]. The idea that reduction of individual amino acids can slow growth and aging was identified several decades ago [3]. In 1993, Orentreich et al. published a seminal report revealing the effects of dietary methionine restriction on lifespan extension in male Fischer 344 (F344) rats [4]. By restricting the methionine content from 0.86 to 0.17 g per 100 g diet (~80% reduction) throughout the adult lifespan of the animals, the authors observed an approximate 40% extension in average lifespan compared to unrestricted rats. Coupled with the observation that methionine restricted animals maintained a lower body weight while increasing their relative food intake, this report concluded that dietary methionine restriction eliminates growth while increasing lifespan. Since this original publication, dietary methionine restriction has gained interest as a research model to aid in the prevention and treatment of obesity-related metabolic diseases.

Subsequent investigations in rodent models indicate that the range of dietary methionine restriction which elicits leanness without protein wasting and food aversion is 0.12 to 0.25 g per 100 g diet, as compared to the 0.43 to 0.86 g per 100 g in complete rodent diets [5][6][5,6]. However, most studies to date utilize methionine levels ranging between 0.12 to 0.17 g per 100 g diet with 0.17 g per 100 g diet the most well-studied restriction level. It is also important to note that the majority of methionine restriction diets are based on a zero-cysteine dietary background. Work by several labs have emphasized the importance of coupling methionine restriction with total dietary depletion of cysteine, the other major dietary sulfur amino acid [6][7][8][9][6,7,8,9]. Indeed, metabolic and body weight changes are completely reversible with the addition of 0.2 g cysteine per 100 g diet to a methionine restricted diet [10]. Consequently, methionine restriction may be more accurately described as sulfur amino acid (SAA) restriction (SAAR).

Much of the recent interest paid to SAAR stems from the observation that rodents subjected to the restricted diet display increased healthspan. Health improvements induced by SAAR include attenuation of body weight and body fat gain. Investigation into the altered body composition seen in rodents fed SAAR points to increases in energy expenditure as well as heat increment of feeding [11]. Dietary SAAR also reduces fat deposition, both overall and in inguinal, epididymal, and retroperitoneal fat pads, and simultaneously induces browning of white adipose tissue [11][12][11,12]. This reduction in fat deposition is the combined result of increased expression of fatty acid oxidation genes in adipose tissue and decreased expression of lipogenic genes in liver and white adipose, contributing to a shift towards fatty acid oxidation on a whole-body level [11][13][11,13]. Additionally, triglyceride content in serum and liver is decreased [12][13][12,13]. Notably, SAAR ameliorates liver steatosis associated with diet-induced obesity and prevents progression of hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice [13][14][13,14]. Furthermore, SAAR prevents type 2 diabetes in New Zealand Obese mice [15].

The reduced overall adiposity in SAA restricted rodents corresponds with reductions in fasting concentrations of insulin, glucose, thyroxine, insulin-like growth factor-1 and leptin, and increases in serum adiponectin [5][11][14][16][17][5,11,14,16,17]. Part of the mechanism behind the improved fasting insulin is dependent on SAAR-mediated increased sensitivity to insulin-dependent Akt phosphorylation in the liver [17]. In addition, obese mice subjected to dietary SAAR display increased plasma membrane localization of the GLUT4 glucose transporter and glycogen synthesis in gastrocnemius muscle, potentially contributing to improved insulin sensitivity in conjunction with SAAR [18].

Other systemic effects of dietary SAAR include delayed cataract development, downregulation of arrhythmogenic, hypertrophic, and cardiomyopathy signaling pathways in the heart, and attenuated cardiac response to beta adrenergic stimulation [19]. On the other hand, dietary SAAR may contribute to reduced bone mass and altered intrinsic and extrinsic bone strength. Notably, recent findings suggest that male mice subjected to dietary SAAR display decreased bone tissue density in both trabecular and cortical bone, simultaneous with an observed induction in fat accumulation in bone marrow [20]. As bone mass and quality are important predictors of health with advancing age, this topic remains to be further explored in greater detail [14][21][14,21].

At a glance, dietary SAAR appears to recapitulate many of the beneficial effects attributed to caloric restriction; however, it is worth noting that dietary SAAR elicits a transcriptional response in liver that partly differs from caloric restriction [22]. Furthermore, the specific transcriptional response to insufficiency of different single amino acids shows that deprivation or restriction of methionine elicits a hepatic response that is divergent from restriction of the other essential amino acids [[221][23][24][25],22,23,24]. Taken together, the current literature supports a view in which SAAR, within a limited range of intakes, improves metabolic health by uniquely altering target tissues.

2. The Integrated Stress Response and Detection of Amino Acid Insufficiency

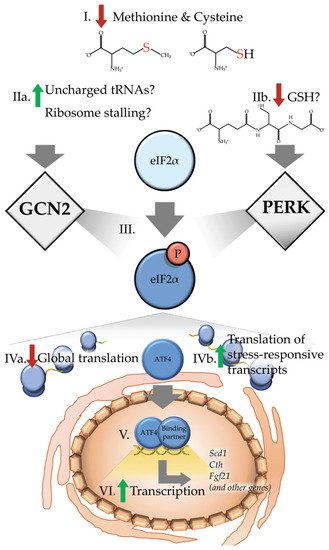

Throughout evolution, all living organisms have encountered periods of nutrient scarcity. In order to ensure survival during such periods, intricate and overlapping cellular processes have evolved to promote resilience and metabolic homeostasis. Many of these signaling networks are evolutionary well-conserved. Among these networks, the integrated stress response (ISR) is identified in all eukaryotic organisms as a means to allow for conservation of resources to adapt to environmental stress, ultimately improving survivability [26][25]. A key feature of the classical or canonical ISR is the concept that a variety of cellular stresses are sensed by a family of protein kinases which together function as stress response regulators. These ISR regulators are: Protein Kinase R (PKR), which is stimulated by viral double stranded RNA; PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), which is activated by ER stress; heme regulated inhibitor (HRI), which modulates globin synthesis in response to heme deprivation; and general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2), which senses amino acid insufficiency, ribosomal stalling, and cellular damage by UV light. Activation of these ISR regulators converge at the point of phosphorylation of the GTPase activating protein, eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) at serine 51 of its α subunit. This covalent modification converts eIF2 into a competitive inhibitor of its guanine nucleotide exchange factor, eIF2B [27][28][26,27]. Inhibition of eIF2B then slows the rate at which eIF2 can be re-loaded with GTP. Ultimately, reduced rates of GTP-GDP exchange on eIF2, an essential step in mRNA translation re-initiation, alters gene-specific translation. As one of the branches of the ISR, early detection of amino acid insufficiency by GCN2 functions to delay catastrophic depletion of the intracellular amino acid pool by reducing the bulk client load for protein synthesis (Figure 1). In brief, as cytosolic levels of specific amino acids decrease, aminoacylation levels of the cognate tRNAs also decline. These deacylated or ‘uncharged’ tRNAs bind GCN2 and activate the kinase through dimerization and autophosphorylation [29][30][31][28,29,30]. In addition, emerging evidence points towards sensing of ribosomal stalling as a potent activator of GCN2, plausibly mediated by the heteropentameric protein complex P-stalk [32][33][31,32].

Figure 1. Dietary sulfur amino acid restriction results in activation of the integrated stress response. (I) Upon reduced levels of methionine and cysteine, a canonical integrated stress response (ISR) would predict or hypothesize that (IIa) levels of the uncharged cognate tRNAs may accumulate at or near the ribosome. Alternatively, other recent reports suggest increased ribosome stalling as a potential means of activating the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) kinase general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2). In addition to activation of GCN2, dietary sulfur amino acid restriction (IIb) reduces levels of intracellular glutathione (GSH), which may in turn activate protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). Collectively, current evidence suggests that both of these paths results in (III) phosphorylation of the αsubunit of eIF2. Phosphorylation of eIF2 (IVa) decreases global translation (IVb) which increases preferential translation of transcripts containing upstream open reading frames such as the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor Atf4. (V) Upon being translated, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) enters the nucleus and interacts with binding partners to (VI) induce transcription of target genes, including stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1 (Scd1), cystathionine gamma-lyase (Cth) and fibroblast growth factor 21 (Fgf21), as well as many other genes.

3. Restriction of Sulfur Amino Acids Reduces Protein Synthesis Independent of GCN2

In several growth restricted rodent models with long life, reduced protein synthesis is a shared response [34][35][42,43]. Following detection of reduced levels of intracellular amino acids by GCN2, global translation initiation is reduced to allow for conservation of resources and ultimately maintenance of protein homeostasis. Therefore, the reduced availability of essential sulfur amino acids may reduce protein synthesis. To that end, a number of reports have investigated the ability of dietary SAAR to alter protein synthesis rates [10][36][37][10,44,45]. One study found that in the liver and skeletal muscle of mice fed SAAR for five weeks, protein synthesis rates are reduced in mixed and cytosolic protein fractions but not in the mitochondrial fraction [36][44]. The maintenance of mitochondrial protein synthesis is supportive of the notion that improved mitochondrial proteostasis supports longer lifespan of rodents [35][43]. In contrast, another study showed that SAA restricted male rats display reduced mixed fractional synthesis rates in liver but not in skeletal muscle nor in hippocampus [37][45]. Tissue-specific differences between studies may be due to the level of SAAR, a concept that requires further investigation.

While dietary SAAR is shown to reduce rates of protein synthesis in tissues in vivo, how this dietary change is detected is less clear. Interestingly, one study found that the global loss of Gcn2 did not prevent reductions in protein synthesis rates in both liver and skeletal muscle. Instead, Gcn2 deleted mice fed a SAA restricted diet retained more body fat as compared to intact mice. This finding differs from that reported in Gcn2 deleted mice fed a leucine-devoid diet which showed sustained liver protein synthesis at the expense of muscle mass and greater body weight loss as compared to intact mice [38][46]. These differences may be a function of the timing of the measurement, choice of amino acid deprivation or age of the mice, or the combination of these factors.

Of interest, several reports collectively show that while GCN2 may be activated by SAAR, it is not the only sensor involved. [10][38][10,46]. Instead, similar to protein restriction, GCN2 may play a role in dampening growth signaling via the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 pathway or in complimenting the action of other stress kinases such as AMP-activated protein kinase or the mitogen activated kinases MEK/ERK [39][47]. Irrespectively, it appears clear that the whole organism carries functional overlap in amino acid sensing and signaling in individual tissues. Such findings point to the necessity to further study these overlapping cellular responses to dietary SAAR.

4. Sulfur Amino Acid Restriction Promotes Gene-Specific Translation of ATF4 Regardless of eIF2 Phosphorylation

A key component of the canonical ISR response to deprivation of most amino acids is increased ATF4 synthesis which activates the expression of cytoprotective genes [40][41][36,48]. Rats fed a SAA-restricted diet for seven days showed higher levels of hepatic eIF2 phosphorylation and ATF4 protein expression [42][43][49,50]. In most studies utilizing SAA deprivation or prolonged SAAR, the phosphorylation of eIF2 corresponds with ATF4 synthesis but one should hesitate to conclude cause and effect. For example, it was found that hepatic Atf4 expression was elevated in mice after two days of feeding a SAA restricted diet even though levels of eIF2 phosphorylation and GDP/GTP exchange rates on eIF2 were unchanged relative to animals fed a control diet. These results indicate an uncoupling between eIF2 phosphorylation and ATF4 synthesis in liver [36][44]. Interestingly, later timepoints in the same study showed the expected relationship between increased phosphorylation of eIF2, reduced rates of GDP/GTP exchange, and increased ATF4 target gene expression in liver. The early uncoupling between eIF2 phosphorylation and ATF4 target gene expression in response to SAAR suggests the presence of a non-canonical ISR; in other words, other post-transcriptional mechanisms may regulate ATF4 levels in vivo, such as altered protein stability. Additional research efforts are necessary to uncover the regulation of ATF4 by SAAR.

5. Sulfur Amino Acid Restriction Promotes Expression of ATF4 Target Genes Which Includes Fibroblast Growth Factor 21

As detailed above, the ATF4-mediated transcriptional response is tailored to the specific cellular stress. Indeed, individual amino acid stress responses are heterogeneous and in vitro studies have revealed that the methionine-deprived transcriptional response is unique [23]. Furthermore, while both amino acid deprivation and restriction results in transcriptional changes in ATF4 target genes, the execution of the transcriptome favors apoptotic signaling only when the insufficiency is severely intense or sustained [40][36]. The timing and determinants of this shift in cell fate remains unclear and is likely a function of the interactions that occur between ATF4 and other bZIP transcription factors and the complex network of interacting binding proteins that act as transcriptional coactivators and corepressors. Intriguingly, much in this area remains to be uncovered.

Among the ATF4 gene target identified under conditions of protein dilution and amino acid deprivation is fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), an endocrine member of the FGF superfamily [44][45][46][47][48][49][51,52,53,54,55,56]. As a predominantly hepatic-derived endocrine signal of nutrient stress, FGF21 interacts with a number of target tissues [50][57]. Identification of FGF21 target tissues, including liver, various adipose deposits and regions of the brain have been made based on expression of the receptor, FGFR, and the requisite co-receptor β-klotho. Upon interaction with the receptor constellation, FGF21 results in stimulation of a number of metabolic effects, including increased mitochondrial uncoupling and thus energy expenditure as well as increased free fatty acid oxidation [50][57].

While various forms of amino acid insufficiency can induce the hepatic synthesis and secretion of FGF21 into the blood, the precise upstream mechanisms initially remained elusive. Involvement of the ISR in the physiological induction of FGF21 is supported by identification of up to three AAREs in the promoter region of Fgf21 [51][52][58,59]. Corroborating these findings, mice respond to protein restriction by increasing ATF4 binding to AAREs in the Fgf21 promoter region [53][60]. Accordingly, while the ATF4 binding coincided with increased circulating FGF21 in genetically intact animals, the response was perturbed in animals lacking Gcn2. Interestingly, loss of Gcn2 did not completely abrogate the ATF4-mediated increase in FGF21, but rather caused a noticeable temporal delay. It was subsequently concluded that while GCN2/ATF4 signaling is imperative in the acute response to protein restriction, it is not essential; suggesting that upon loss of Gcn2, other regulators may facilitate induction of FGF21. This idea was tested in a subsequent study feeding a SAA restricted diet to mice with Atf4 deleted whole body and showed that FGF21 production was delayed but not blocked [542]. Importantly, this study also identified biological sex as an important variable in the effect of dietary SAAR on FGF21 production, with females showing more modest changes in FGF21 and body composition as compared to males. Notably, these findings contrast with drug-mediated amino acid starvation which requires GCN2/ATF4 signaling for hepatic expression of Fgf21 in both sexes [473][55][54]. In total, these studies suggest that the canonical GCN2-eIF2-ATF4 axis contributes to but does not exclusively control Fgf21 expression during dietary SAAR.

In summary, the currently available literature is supportive of FGF21 as a central mediator in the physiological response to dietary SAAR. While the importance of FGF21 during SAAR is recognized, the upstream control remains elusive and appears complex in its nature, as pointed in a recent review [56][62]. In revealing the precise mechanisms behind the upstream control of FGF21 during dietary SAAR, future efforts will need to consider the relationships between the ISR and other nutrient responsive signaling networks in both females and males.

References

- Carpenter, K.J. The history of enthusiasm for protein. J. Nutr. 1986, 116, 1364–1370. William O. Jonsson; Emily T. Mirek; Ronald C. Wek; Tracy G. Anthony; Activation and execution of the hepatic integrated stress response by dietary essential amino acid deprivation is amino acid specific. The FASEB Journal 2022, 36, e22396, 10.1096/fj.202200204rr.

- Leto, S.; Kokkonen, G.C.; Barrows, C.H. Dietary protein, life span, and biochemical variables in female mice. J. Gerontol. 1976, 31, 144–148. William O Jonsson; Nicholas S Margolies; Emily T Mirek; Qian Zhang; Melissa A Linden; Cristal M Hill; Christopher Link; Nazmin Bithi; Brian Zalma; Jordan L Levy; et al.Ashley P PettitJoshua W MillerChristopher HineChristopher D MorrisonThomas W GettysBenjamin F MillerKaryn L HamiltonRonald C WekTracy G Anthony Physiologic Responses to Dietary Sulfur Amino Acid Restriction in Mice Are Influenced by Atf4 Status and Biological Sex. The Journal of Nutrition 2021, 151, 785-799, 10.1093/jn/nxaa396.

- Segall, P.E.; Timiras, P.S. Patho-physiologic findings after chronic tryptophan deficiency in rats: A model for delayed growth and aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1976, 5, 109–124. Rana J. T. Al-Baghdadi; Inna A. Nikonorova; Emily T. Mirek; Yongping Wang; Jinhee Park; William J. Belden; Ronald C. Wek; Tracy G. Anthony; Role of activating transcription factor 4 in the hepatic response to amino acid depletion by asparaginase.. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1272, 10.1038/s41598-017-01041-7.

- Orentreich, N.; Matias, J.R.; DeFelice, A.; Zimmerman, J.A. Low Methionine Ingestion by Rats Extends Life Span Orentreich Foundation for the Advancement. Nutr. Requir. Interact. 1993, 269–274.

- Miller, R.A.; Buehner, G.; Chang, Y.; Harper, J.M.; Sigler, R.; Smith-Wheelock, M. Methionine-deficient diet extends mouse lifespan, slows immune and lens aging, alters glucose, T4, IGF-I and insulin levels, and increases hepatocyte MIF levels and stress resistance. Aging Cell 2005, 4, 119–125.

- Forney, L.A.; Wanders, D.; Stone, K.P.; Pierse, A.; Gettys, T.W. Concentration-Dependent Linkage of Dietary Methionine Restriction to the Components of its Metabolic Phenotype. Obesity 2017, 25, 730–738.

- Elshorbagy, A.K.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Refsum, H.; Smith, A.D.; Mattocks, D.A.L.; Perrone, C.E. Sulfur amino acids in methionine-restricted rats: Hyperhomocysteinemia. Nutrition 2010, 26, 1201–1204.

- Elshorbagy, A.K.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Mattocks, D.A.L.; Plummer, J.D.; Smith, A.D.; Drevon, C.A.; Refsum, H.; Perrone, C.E. Cysteine supplementation reverses methionine restriction effects on rat adiposity: Significance of stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase. J. Lipid Res. 2011, 52, 104–112.

- Sikalidis, A.K.; Mazor, K.M.; Kang, M.; Liu, H.; Stipanuk, M.H. Total 4EBP1 Is Elevated in Liver of Rats in Response to Low Sulfur Amino Acid Intake. J. Amino Acids 2013, 2013, 1–11.

- Wanders, D.; Stone, K.P.; Forney, L.A.; Cortez, C.C.; Dille, K.N.; Simon, J.; Xu, M.; Hotard, E.C.; Nikonorova, I.A.; Pettit, A.P.; et al. Role of GCN2-independent signaling through a noncanonical PERK/NRF2 pathway in the physiological responses to dietary methionine restriction. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1499–1510.

- Hasek, B.E.; Stewart, L.K.; Henagan, T.M.; Boudreau, A.; Lenard, N.R.; Black, C.; Shin, J.; Huypens, P.; Malloy, V.L.; Plaisance, E.P.; et al. Dietary methionine restriction enhances metabolic flexibility and increases uncoupled respiration in both fed and fasted states. AJP Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 299, R728–R739.

- Perrone, C.E.; Mattocks, D.A.L.; Jarvis-Morar, M.; Plummer, J.D.; Orentreich, N. Methionine restriction effects on mitochondrial biogenesis and aerobic capacity in white adipose tissue, liver, and skeletal muscle of F344 rats. Metabolism 2010, 59, 1000–1011.

- Malloy, V.L.; Perrone, C.E.; Mattocks, D.A.L.; Ables, G.P.; Caliendo, N.S.; Orentreich, D.S.; Orentreich, N. Methionine restriction prevents the progression of hepatic steatosis in leptin-deficient obese mice. Metabolism 2013, 62, 1651–1661.

- Ables, G.P.; Perrone, C.E.; Orentreich, D.; Orentreich, N. Methionine-Restricted C57BL/6J Mice Are Resistant to Diet-Induced Obesity and Insulin Resistance but Have Low Bone Density. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51357.

- Castaño-Martinez, T.; Schumacher, F.; Schumacher, S.; Kochlik, B.; Weber, D.; Grune, T.; Biemann, R.; McCann, A.; Abraham, K.; Weikert, C.; et al. Methionine restriction prevents onset of type 2 diabetes in NZO mice. FASEB J. 2019.

- Malloy, V.L.; Krajcik, R.A.; Bailey, S.J.; Hristopoulos, G.; Plummer, J.D.; Orentreich, N. Methionine restriction decreases visceral fat mass and preserves insulin action in aging male Fischer 344 rats independent of energy restriction. Aging Cell 2006, 5, 305–314.

- Stone, K.P.; Wanders, D.; Orgeron, M.; Cortez, C.C.; Gettys, T.W. Mechanisms of increased in vivo insulin sensitivity by dietary methionine restriction in mice. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3721–3733.

- Luo, T.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Wu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, J.; Shi, Y.-H.; Le, G. Dietary methionine restriction improves glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle of obese mice. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2676–2690.

- Ables, G.P.; Ouattara, A.; Hampton, T.G.; Cooke, D.; Perodin, F.; Augie, I.; Orentreich, D.S. Dietary methionine restriction in mice elicits an adaptive cardiovascular response to hyperhomocysteinemia. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–10.

- Plummer, J.; Park, M.; Perodin, F.; Horowitz, M.C.; Hens, J.R. Methionine-Restricted Diet Increases miRNAs That Can Target RUNX2 Expression and Alters Bone Structure in Young Mice. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 31–42.

- Huang, T.-H.; Lewis, J.L.; Lin, H.-S.; Kuo, L.-T.; Mao, S.-W.; Tai, Y.-S.; Chang, M.-S.; Ables, G.P.; Perrone, C.E.; Yang, R.-S. A Methionine-Restricted Diet and Endurance Exercise Decrease Bone Mass and Extrinsic Strength but Increase Intrinsic Strength in Growing Male Rats1–3. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 621–630.

- Ghosh, S.; Wanders, D.; Stone, K.P.; Van, N.T.; Cortez, C.C.; Gettys, T.W. A systems biology analysis of the unique and overlapping transcriptional responses to caloric restriction and dietary methionine restriction in rats. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2577–2590.

- Tang, X.; Keenan, M.M.; Wu, J.; Lin, C.A.; Dubois, L.; Thompson, J.W.; Freedland, S.J.; Murphy, S.K.; Chi, J.T. Comprehensive Profiling of Amino Acid Response Uncovers Unique Methionine-Deprived Response Dependent on Intact Creatine Biosynthesis. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005158.

- Lees, E.K.; Banks, R.; Cook, C.; Hill, S.; Morrice, N.; Grant, L.; Mody, N.; Delibegovic, M. Direct comparison of methionine restriction with leucine restriction on the metabolic health of C57BL/6J mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10.

- William O. Jonsson; Emily T. Mirek; Ronald C. Wek; Tracy G. Anthony; Activation and execution of the hepatic integrated stress response by dietary essential amino acid deprivation is amino acid specific. The FASEB Journal 2022, 36, e22396, 10.1096/fj.202200204rr.

- Pakos-Zebrucka, K.; Koryga, I.; Mnich, K.; Ljujic, M.; Samali, A.; Gorman, A.M. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1374–1395.

- Berlanga, J.J.; Santoyo, J.; de Haro, C. Characterization of a mammalian homolog of the GCN2 eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 265, 754–762.

- Wek, R.C. Role of eIF2α kinases in translational control and adaptation to cellular stress. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a032870.

- Wek, R.C.; Jackson, B.M.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Juxtaposition of domains homologous to protein kinases and histidyl-tRNA synthetases in GCN2 protein suggests a mechanism for coupling GCN4 expression to amino acid availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 4579–4583.

- Anda, S.; Zach, R.; Grallert, B. Activation of Gcn2 in response to different stresses. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182143.

- Narasimhan, J.; Staschke, K.A.; Wek, R.C. Dimerization is required for activation of eIF2 kinase Gcn2 in response to diverse environmental stress conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 22820–22832.

- Ishimura, R.; Nagy, G.; Dotu, I.; Chuang, J.H.; Ackerman, S.L. Activation of GCN2 kinase by ribosome stalling links translation elongation with translation initiation. eLife 2016, 5, 1–22.

- Inglis, A.J.; Masson, G.R.; Shao, S.; Perisic, O.; McLaughlin, S.H.; Hegde, R.S.; Williams, R.L. Activation of GCN2 by the ribosomal P-stalk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4946–4954.

- Drake, J.C.; Bruns, D.R.; Peelor, F.F.; Biela, L.M.; Miller, R.A.; Miller, B.F.; Hamilton, K.L. Long-lived Snell dwarf mice display increased proteostatic mechanisms that are not dependent on decreased mTORC1 activity. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 474–482.

- Hamilton, K.L.; Miller, B.F. Mitochondrial proteostasis as a shared characteristic of slowed aging: The importance of considering cell proliferation. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 6401–6407.

- Pettit, A.P.; Jonsson, W.O.; Bargoud, A.R.; Mirek, E.T.; Peelor, F.F.; Wang, P.; Gettys, T.W.; Kimball, S.R.; Miller, B.F.; Hamilton, K.L.; et al. Dietary Methionine Restriction Regulates Liver Protein Synthesis and Gene Expression Independently of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 Phosphorylation in Mice. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1031–1040.

- Nichenametla, S.N.; Mattocks, D.A.L.; Malloy, V.L.; Pinto, J.T. Sulfur amino acid restriction-induced changes in redox-sensitive proteins are associated with slow protein synthesis rates. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1418, 80–94.

- Anthony, T.G.; McDaniel, B.J.; Byerley, R.L.; McGrath, B.C.; Cavener, D.B.; McNurlan, M.A.; Wek, R.C. Preservation of liver protein synthesis during dietary leucine deprivation occurs at the expense of skeletal muscle mass in mice deleted for eIF2 kinase GCN2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 36553–36561.

- Chotechuang, N.; Azzout-Marniche, D.; Bos, C.; Chaumontet, C.; Gausserès, N.; Steiler, T.; Gaudichon, C.; Tomé, D. mTOR, AMPK, and GCN2 coordinate the adaptation of hepatic energy metabolic pathways in response to protein intake in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2009, 297, E1313–E1323.

- Kilberg, M.S.; Shan, J.; Su, N. ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 436–443.

- Baird, T.; Wek, R. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 phosphorylation and translational control in metabolism. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 307–321.

- Sikalidis, A.K.; Stipanuk, M.H. Growing Rats Respond to a Sulfur Amino Acid–Deficient Diet by Phosphorylation of the α Subunit of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 Heterotrimeric Complex and Induction of Adaptive Components of the Integrated Stress Response. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1080–1085.

- Sikalidis, A.K.; Lee, J.I.; Stipanuk, M.H. Gene expression and integrated stress response in HepG2/C3A cells cultured in amino acid deficient medium. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 159–171.

- Nishimura, T.; Nakatake, Y.; Konishi, M.; Itoh, N. Identification of a novel FGF, FGF-21, preferentially expressed in the liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expr. 2000, 1492, 203–206.

- Kharitonenkov, A.; Shiyanova, T.L.; Koester, A.; Ford, A.M.; Micanovic, R.; Galbreath, E.J.; Sandusky, G.E.; Hammond, L.J.; Moyers, J.S.; Owens, R.A.; et al. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 1627–1635.

- Laeger, T.; Henagan, T.M.; Albarado, D.C.; Redman, L.M.; Bray, G.A.; Noland, R.C.; Münzberg, H.; Hutson, S.M.; Gettys, T.W.; Schwartz, M.W.; et al. FGF21 is an endocrine signal of protein restriction. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3913–3922.

- Wilson, G.J.; Lennox, B.A.; She, P.; Mirek, E.T.; Al Baghdadi, R.J.T.; Fusakio, M.E.; Dixon, J.L.; Henderson, G.C.; Wek, R.C.; Anthony, T.G. GCN2 is required to increase fibroblast growth factor 21 and maintain hepatic triglyceride homeostasis during asparaginase treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2015, 308, E283–E293.

- Hill, C.M.; Laeger, T.; Albarado, D.C.; McDougal, D.H.; Berthoud, H.R.; Münzberg, H.; Morrison, C.D. Low protein-induced increases in FGF21 drive UCP1- dependent metabolic but not thermoregulatory endpoints. Sci. Rep. 2017, 15, 8209.

- Maida, A.; Zota, A.; Sjøberg, K.A.; Schumacher, J.; Sijmonsma, T.P.; Pfenninger, A.; Christensen, M.M.; Gantert, T.; Fuhrmeister, J.; Rothermel, U.; et al. A liver stress-endocrine nexus promotes metabolic integrity during dietary protein dilution. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3263–3278.

- Fisher, F.M.; Maratos-Flier, E. Understanding the Physiology of FGF21. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 223–241.

- De Sousa-Coelho, A.L.; Marrero, P.F.; Haro, D. Activating transcription factor 4-dependent induction of FGF21 during amino acid deprivation. Biochem. J. 2012, 443, 165–171.

- Maruyama, R.; Shimizu, M.; Li, J.; Inoue, J.; Sato, R. Fibroblast growth factor 21 induction by activating transcription factor 4 is regulated through three amino acid response elements in its promoter region. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 929–934.

- Laeger, T.; Albarado, D.C.; Burke, S.J.; Trosclair, L.; Hedgepeth, J.W.; Berthoud, H.R.; Gettys, T.W.; Collier, J.J.; Münzberg, H.; Morrison, C.D. Metabolic Responses to Dietary Protein Restriction Require an Increase in FGF21 that Is Delayed by the Absence of GCN2. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 707–716.

- William O Jonsson; Nicholas S Margolies; Emily T Mirek; Qian Zhang; Melissa A Linden; Cristal M Hill; Christopher Link; Nazmin Bithi; Brian Zalma; Jordan L Levy; et al.Ashley P PettitJoshua W MillerChristopher HineChristopher D MorrisonThomas W GettysBenjamin F MillerKaryn L HamiltonRonald C WekTracy G Anthony Physiologic Responses to Dietary Sulfur Amino Acid Restriction in Mice Are Influenced by Atf4 Status and Biological Sex. The Journal of Nutrition 2021, 151, 785-799, 10.1093/jn/nxaa396.

- Rana J. T. Al-Baghdadi; Inna A. Nikonorova; Emily T. Mirek; Yongping Wang; Jinhee Park; William J. Belden; Ronald C. Wek; Tracy G. Anthony; Role of activating transcription factor 4 in the hepatic response to amino acid depletion by asparaginase.. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1272, 10.1038/s41598-017-01041-7.

- Forney, L.A.; Stone, K.P.; Wanders, D.; Gettys, T.W. Sensing and signaling mechanisms linking dietary methionine restriction to the behavioral and physiological components of the response. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2017, 51, 36–45.

More