Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a complex, chronic, debilitating condition impacting millions worldwide. Genetic, environmental, and epigenetic factors are known to contribute to the development of AUD. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of regulatory RNAs, commonly referred to as the “dark matter” of the genome, with little to no protein-coding potential. LncRNAs have been implicated in numerous processes critical for cell survival, suggesting that they play important functional roles in regulating different cell processes. LncRNAs were also shown to display higher tissue specificity than protein-coding genes and have a higher abundance in the brain and central nervous system, demonstrating a possible role in the etiology of psychiatric disorders.

- long non-coding RNA

- neuropsychiatric disorders

- alcohol use disorder

1. The RNA World

2. lncRNA Functions

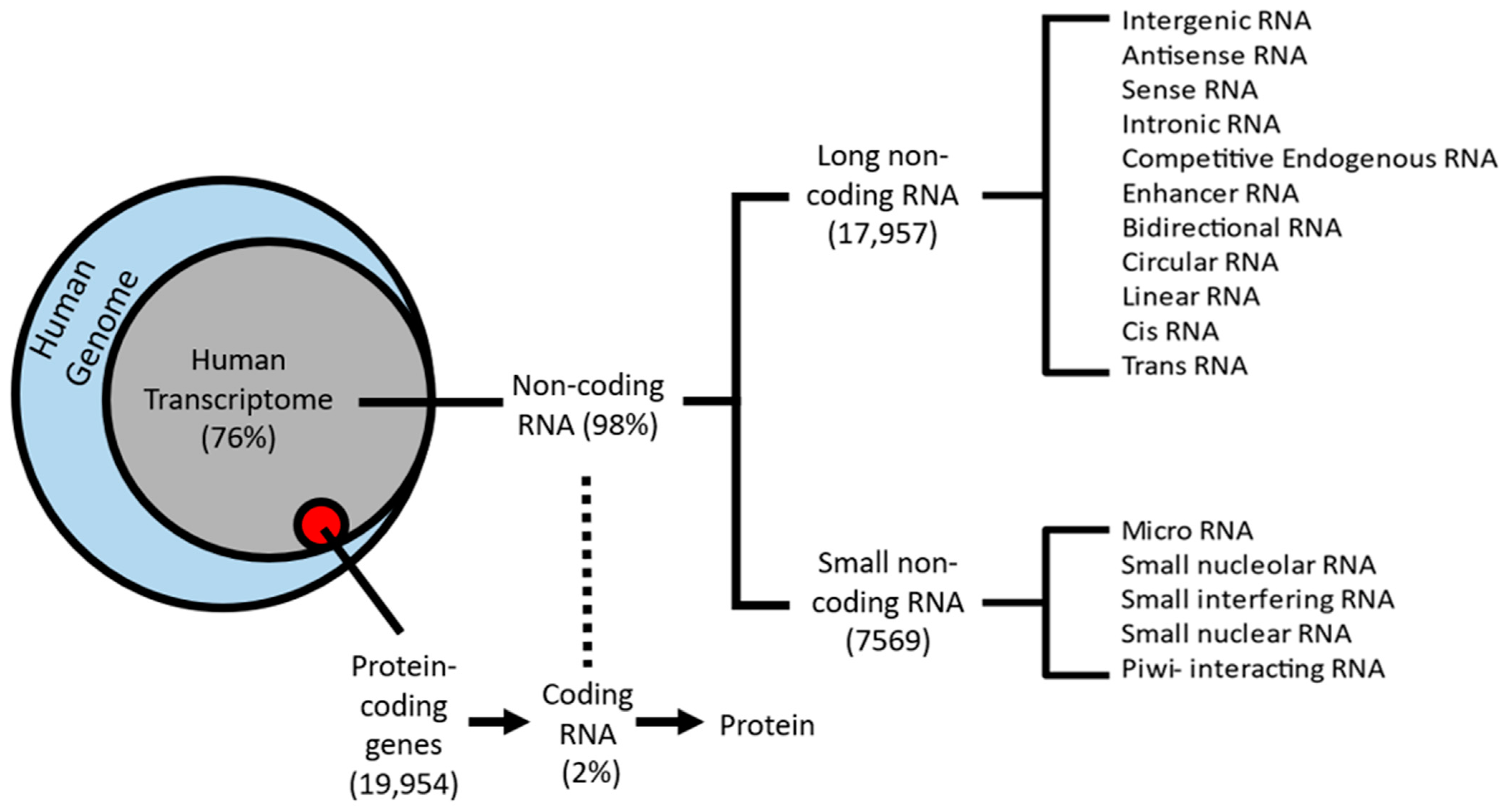

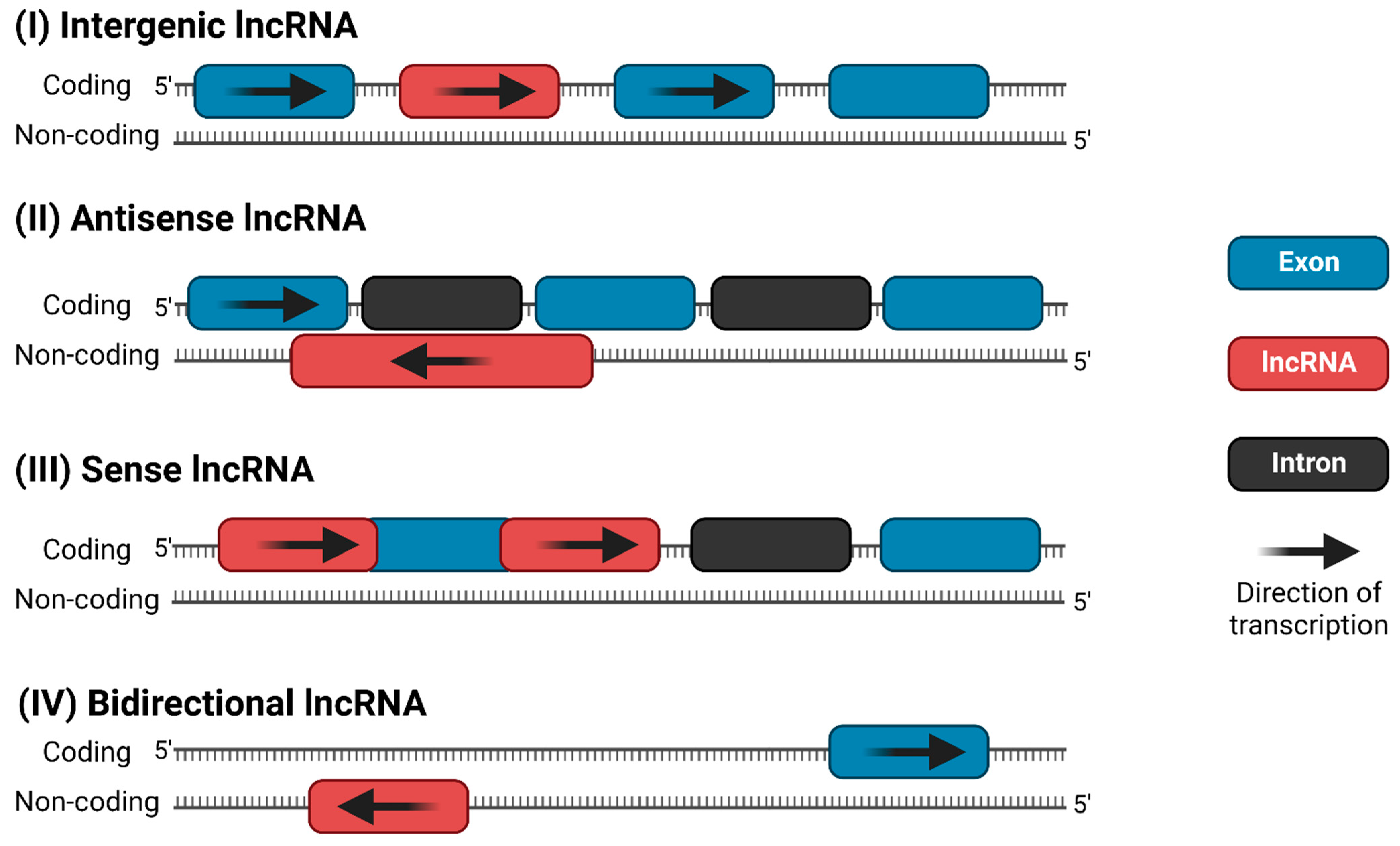

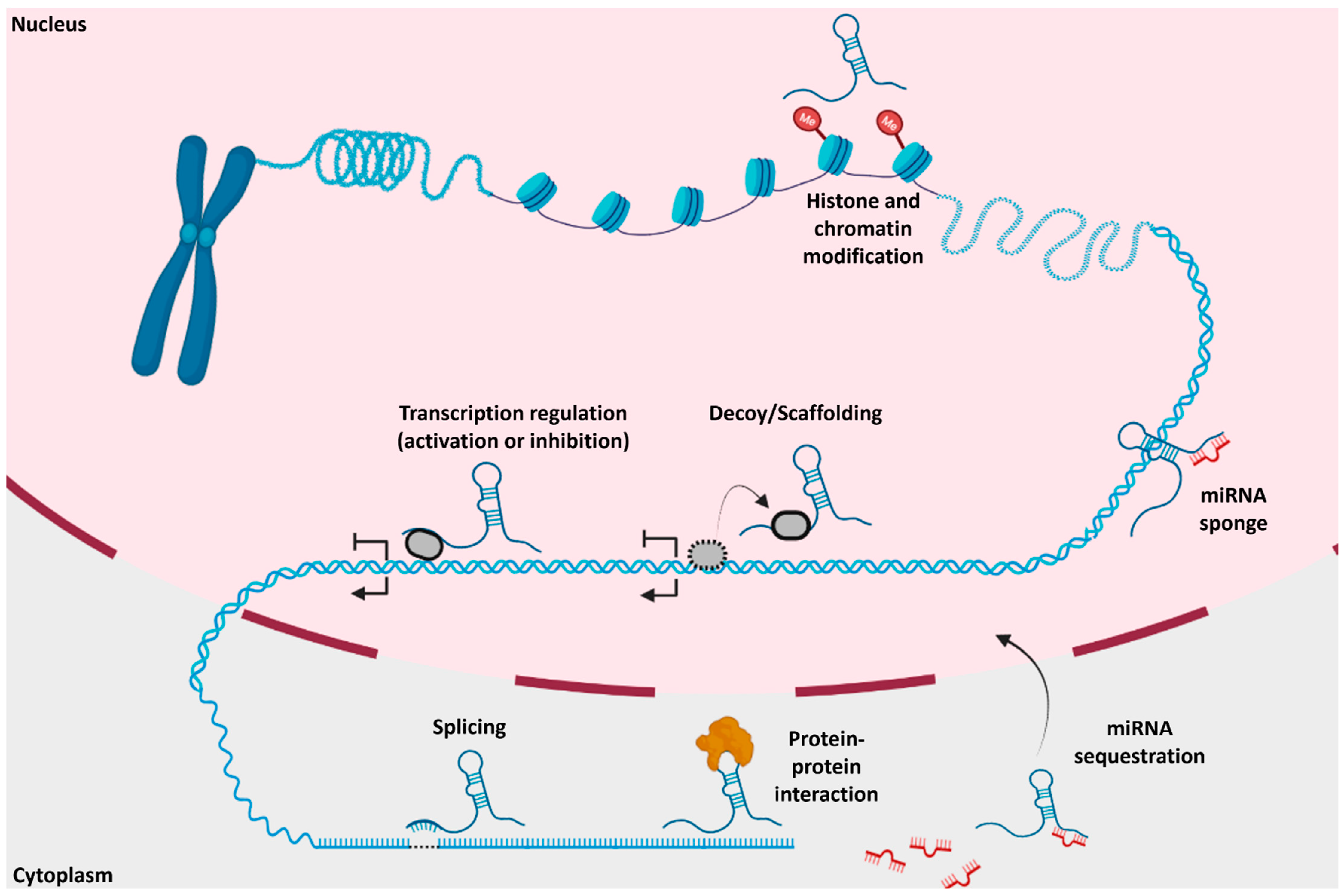

Like protein-coding genes, lncRNAs can be transcribed from either the sense or antisense strand of DNA [10]. LncRNAs exhibit a wide variety of cellular and molecular functions, depending on their subcellular localization; however, there is no universally agreed-upon classification system. Accounting for functional overlap, 11 distinct species of lncRNAs have been described, which are summarized in Figure 1. Among these, the four most discussed categories of lncRNAs in the literature are (i) long intergenic (lincRNA), (ii) antisense, (iii) sense intronic, and (iv) bidirectional lncRNAs (Figure 2) [14][15]. LincRNAs are located between protein-coding genes, whereas the antisense lncRNAs overlap one or more exons on the opposite strand of mRNA, and sense lncRNAs overlap one or more exons on the same mRNA strand. Bidirectional lncRNAs are transcribed from the promoter of a protein-coding gene in the opposite direction [15][16].

3. Epidemiology of AUD

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a debilitating condition impacting millions of individuals worldwide. In the United States, the average 12-month and lifetime prevalence of AUD is 13.9% and 29.1%, respectively, with males historically having a higher prevalence (i.e., 17.6% and 36.0%) than females (i.e., 10.4% and 22.7%) [41]. An annual average of 87,798 alcohol-attributable deaths (AAD) and 2.5 million years of potential life lost (YPLL) occurred from 2006 through 2010, with similar numbers still occurring over a decade later [42]. The transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5 led to merging alcohol addiction and alcohol dependence into a single AUD diagnosis [43]. A person meeting any 2 of the 11 DSM-5 criteria during the same 12-month period would receive a diagnosis of AUD [44], with the severity of AUD—mild, moderate, or severe—based on the number of criteria met. Examples of criteria include craving for alcohol, neglect of day-to-day activities, difficulty in cutting down on drinking, and failure to fulfill major obligations due to excessive drinking (Table 1). However, integrating these separate diagnoses into one disorder, AUD, poses a challenge to future studies that utilize data obtained prior to DSM-5 implementation. Therefore, it is vital to confirm the new AUD diagnosis through access to patient records. Caution must also be taken to ensure AUD is not used interchangeably with alcohol abuse and alcohol dependency. Some of the studies mentioned below (e.g., Van Booven et al. 2021) disclose whether the patients’ diagnosis is based on DSM-IV or DSM-5 to ensure consistency between different studies utilizing DSM-IV or DSM-5 diagnostic criteria [45]. Future metastudies may also consider merging multiple datasets that represent both DSM-4 and DSM-5. AUD is also highly comorbid, i.e., it has been associated with other substance abuse disorders, major depressive disorder (MDD), and anxiety disorders [41]. Approximately 1 in 5 patients with lifetime AUD will be treated, indicating a strong need to understand genetic and environmental factors contributing to predispositions for acquiring AUD.| DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Drinking longer or more than intended |

| 2 | Tried to quit or decrease levels of drinking, but failed |

| 3 | Sick from the aftereffects |

| 4 | Incapability to not think about drinking |

| 5 | Drinking interferes with your daily life (job, family, school, etc…) |

| 6 | Continued drinking habits regardless of daily life struggles |

| 7 | Loss of pleasure in things you once loved |

| 8 | Reckless behavior (driving, fighting, unsafe sex, etc…) |

| 9 | Continued drinking even if depressed or anxious or experiencing memory problems |

| 10 | Increased tolerance to alcohol |

| 11 | Withdrawal symptoms (shakiness, nausea, sweating, etc…) |

References

- Naidoo, N.; Pawitan, Y.; Soong, R.; Cooper, D.N.; Ku, C.-S. Human genetics and genomics a decade after the release of the draft sequence of the human genome. Hum. Genet. 2011, 5, 577.

- The ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74.

- Pennisi, E. Human Genome Is Much More than Just Genes | Science | AAAS. Science. 2012. Available online: https://www.science.org/content/article/human-genome-much-more-just-genes (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Evans, J.R.; Feng, F.Y.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Bright Side of Dark Matter: LncRNAs in Cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 2775–2782.

- Hu, X.; Sood, A.K.; Dang, C.V.; Zhang, L. The Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer: The Dark Matter Matters. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2018, 48, 8–15.

- Dahariya, S.; Paddibhatla, I.; Kumar, S.; Raghuwanshi, S.; Pallepati, A.; Gutti, R.K. Long Non-Coding RNA: Classification, Biogenesis and Functions in Blood Cells. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 112, 82–92.

- Ponting, C.P.; Oliver, P.L.; Reik, W. Evolution and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 629–641.

- Nie, J.-H.; Li, T.-X.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Liu, J. Roles of Non-Coding RNAs in Normal Human Brain Development, Brain Tumor, and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Non-Coding RNA 2019, 5, 36.

- Spadaro, P.A.; Bredy, T.W. Emerging Role of Non-Coding RNA in Neural Plasticity, Cognitive Function, and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front. Gene. 2012, 3, 132.

- Derrien, T.; Johnson, R.; Bussotti, G.; Tanzer, A.; Djebali, S.; Tilgner, H.; Guernec, G.; Martin, D.; Merkel, A.; Knowles, D.G.; et al. The GENCODE v7 Catalog of Human Long Noncoding RNAs: Analysis of Their Gene Structure, Evolution, and Expression. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1775–1789.

- Wang, K.C.; Chang, H.Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Long Noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 904–914.

- Jarroux, J.; Morillon, A.; Pinskaya, M. History, Discovery, and Classification of LncRNAs. In Long Non Coding RNA Biology; Rao, M.R.S., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 1008, pp. 1–46.

- Bartolomei, M.S.; Zemel, S.; Tilghman, S.M. Parental Imprinting of the Mouse H19 Gene. Nature 1991, 351, 153–155.

- Qu, H.; Fang, X. A Brief Review on the Human Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Project. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2013, 11, 135–141.

- Aliperti, V.; Skonieczna, J.; Cerase, A. Long Non-Coding RNA (LncRNA) Roles in Cell Biology, Neurodevelopment and Neurological Disorders. Non-Coding RNA 2021, 7, 36.

- Balas, M.M.; Johnson, A.M. Exploring the Mechanisms behind Long Noncoding RNAs and Cancer. Non-Coding RNA Res. 2018, 3, 108–117.

- Han, P.; Chang, C.P. Long Non-Coding RNA and Chromatin Remodeling. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 1094–1098.

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, H.; Ren, G.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H. IRWNRLPI: Integrating Random Walk and Neighborhood Regularized Logistic Matrix Factorization for LncRNA-Protein Interaction Prediction. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 239.

- Salmena, L.; Poliseno, L.; Tay, Y.; Kats, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. A CeRNA Hypothesis: The Rosetta Stone of a Hidden RNA Language? Cell 2011, 146, 353–358.

- Carlevaro-Fita, J.; Rahim, A.; Guigó, R.; Vardy, L.A.; Johnson, R. Cytoplasmic Long Noncoding RNAs Are Frequently Bound to and Degraded at Ribosomes in Human Cells. RNA 2016, 22, 867–882.

- Du, Z.; Sun, T.; Hacisuleyman, E.; Fei, T.; Wang, X.; Brown, M.; Rinn, J.L.; Lee, M.G.S.; Chen, Y.; Kantoff, P.W.; et al. Integrative Analyses Reveal a Long Noncoding RNA-Mediated Sponge Regulatory Network in Prostate Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10982.

- Song, J.; Ahn, C.; Chun, C.H.; Jin, E.J. A Long Non-Coding RNA, GAS5, Plays a Critical Role in the Regulation of MiR-21 during Osteoarthritis: THE INTER-REGULATION OF MiR-21 AND GAS5 IN OA. J. Orthop. Res. 2014, 32, 1628–1635.

- Yang, S.; Lim, K.H.; Kim, S.H.; Joo, J.Y. Molecular Landscape of Long Noncoding RNAs in Brain Disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1060–1074.

- Zhao, J.; Sun, B.K.; Erwin, J.A.; Song, J.J.; Lee, J.T. Polycomb Proteins Targeted by a Short Repeat RNA to the Mouse X Chromosome. Science 2008, 322, 750–756.

- Schertzer, M.D.; Braceros, K.C.A.; Starmer, J.; Cherney, R.E.; Lee, D.M.; Salazar, G.; Justice, M.; Bischoff, S.R.; Cowley, D.O.; Ariel, P.; et al. LncRNA-Induced Spread of Polycomb Controlled by Genome Architecture, RNA Abundance, and CpG Island DNA. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 523–537.

- Tsai, M.C.; Manor, O.; Wan, Y.; Mosammaparast, N.; Wang, J.K.; Lan, F.; Shi, Y.; Segal, E.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNA as Modular Scaffold of Histone Modification Complexes. Science 2010, 329, 689–693.

- Jovčevska, I.; Videtič Paska, A. Neuroepigenetics of Psychiatric Disorders: Focus on LncRNA. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 149, 105140.

- Özeş, A.R.; Wang, Y.; Zong, X.; Fang, F.; Pilrose, J.; Nephew, K.P. Therapeutic Targeting Using Tumor Specific Peptides Inhibits Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIR Activity in Ovarian and Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 894.

- Mayfield, R.D. Emerging Roles for NcRNAs in Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol 2017, 60, 31–39.

- DiStefano, J.K. The Emerging Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Human Disease. In Disease Gene Identification; DiStefano, J.K., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1706, pp. 91–110.

- Sun, X.; Wong, D. Long Non-Coding RNA-Mediated Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis and Diabetes. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 6, 17–25.

- Shabgah, A.G.; Norouzi, F.; Hedayati-Moghadam, M.; Soleimani, D.; Pahlavani, N.; Navashenaq, J.G. A Comprehensive Review of Long Non-Coding RNAs in the Pathogenesis and Development of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 22.

- Jiang, M.C.; Ni, J.J.; Cui, W.Y.; Wang, B.Y.; Zhuo, W. Emerging Roles of LncRNA in Cancer and Therapeutic Opportunities. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 1354–1366.

- Barry, G.; Briggs, J.A.; Vanichkina, D.P.; Poth, E.M.; Beveridge, N.J.; Ratnu, V.S.; Nayler, S.P.; Nones, K.; Hu, J.; Bredy, T.W.; et al. The Long Non-Coding RNA Gomafu Is Acutely Regulated in Response to Neuronal Activation and Involved in Schizophrenia-Associated Alternative Splicing. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 486–494.

- Tsuiji, H.; Yoshimoto, R.; Hasegawa, Y.; Furuno, M.; Yoshida, M.; Nakagawa, S. Competition between a Noncoding Exon and Introns: Gomafu Contains Tandem UACUAAC Repeats and Associates with Splicing Factor-1: Competition between Exons and Introns. Genes Cells 2011, 16, 479–490.

- Sone, M.; Hayashi, T.; Tarui, H.; Agata, K.; Takeichi, M.; Nakagawa, S. The MRNA-like Noncoding RNA Gomafu Constitutes a Novel Nuclear Domain in a Subset of Neurons. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 2498–2506.

- Alfaifi, M.; Ali Beg, M.M.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Ahmad, I.; Alkhathami, A.G.; Joshi, P.C.; Alshehri, O.M.; Alamri, A.M.; Verma, A.K. Circulating Long Non-Coding RNAs NKILA, NEAT1, MALAT1, and MIAT Expression and Their Association in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. BMJ. Open Diab. Res. Care 2021, 9, e001821.

- Seki, T.; Yamagata, H.; Uchida, S.; Chen, C.; Kobayashi, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Harada, K.; Matsuo, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Nakagawa, S. Altered Expression of Long Noncoding RNAs in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 117, 92–99.

- Kingwell, K. Double Setback for ASO Trials in Huntington Disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 412–413.

- Chanda, K.; Das, S.; Chakraborty, J.; Bucha, S.; Maitra, A.; Chatterjee, R.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Bhattacharyya, N.P. Altered Levels of Long NcRNAs Meg3 and Neat1 in Cell And Animal Models Of Huntington’s Disease. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 1348–1363.

- Grant, B.F.; Goldstein, R.B.; Saha, T.D.; Chou, S.P.; Jung, J.; Zhang, H.; Pickering, R.P.; Ruan, W.J.; Smith, S.M.; Huang, B.; et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 757.

- Stahre, M.; Roeber, J.; Kanny, D.; Brewer, R.D.; Zhang, X. Contribution of Excessive Alcohol Consumption to Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost in the United States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, 130293.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison between DSM–IV and DSM–5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-use-disorder-comparison-between-dsm (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Van Booven, D.; Li, M.; Rao, J.S.; Blokhin, I.O.; Dayne Mayfield, R.; Barbier, E.; Heilig, M.; Wahlestedt, C. Alcohol Use Disorder Causes Global Changes in Splicing in the Human Brain. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 2.