Physiotherapy deals with the support and promotion of physical recovery after physical injuries or neurological events and conditions. The degeneration of the neuromuscular system over time is an inevitable part of the aging process, a condition that makes physical therapy necessary in the elderly, especially those with additional neurological disorders (NDs). In this context, physiotherapists often have to evaluate and treat elderly patients with loss of cognitive function from aging as well as balance disorders such as cerebral palsy (and movement disorders), degenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, polyneuropathy (e.g., diabetic neuropathy or Guillain–Barré syndrome), peripheral nerve injuries, and acute cases such as patients recovering from stroke and, recently, elders recovering from COVID-19. Most of the therapeutic approaches for neurological rehabilitation include basic elements such as promoting normal movement, controlling abnormal muscle tone, and facilitating function. Furthermore, neurological physiotherapy adopts a problem-based individualized approach, as determined from a thorough evaluation of a patient’s health status. Therefore, the treatment goals for a person recovering from a stroke may be vastly different among patients with similar NDs but different health history. Thus, the treatment approaches used depend on the individual patient and their symptoms and physiotherapy’s rehabilitation goals, so a variety of tools and standard approaches can be applied.

1. Stroke

Strokes are occurring from sudden disruption of blood supply in the brain that results in disturbance of physical and mental functions. Stroke in the brain’s right side impacts the left part of body functions, along with vision and memory loss, while in the left side, it leads to right side body paralysis, along with speech disruption, slow moves, and memory loss. If the stroke occurs in the brain stem it can affect both sides and lead to the patient being in a “locked” position, unable to make any movement below the throat, as well as being unable to speak clearly.

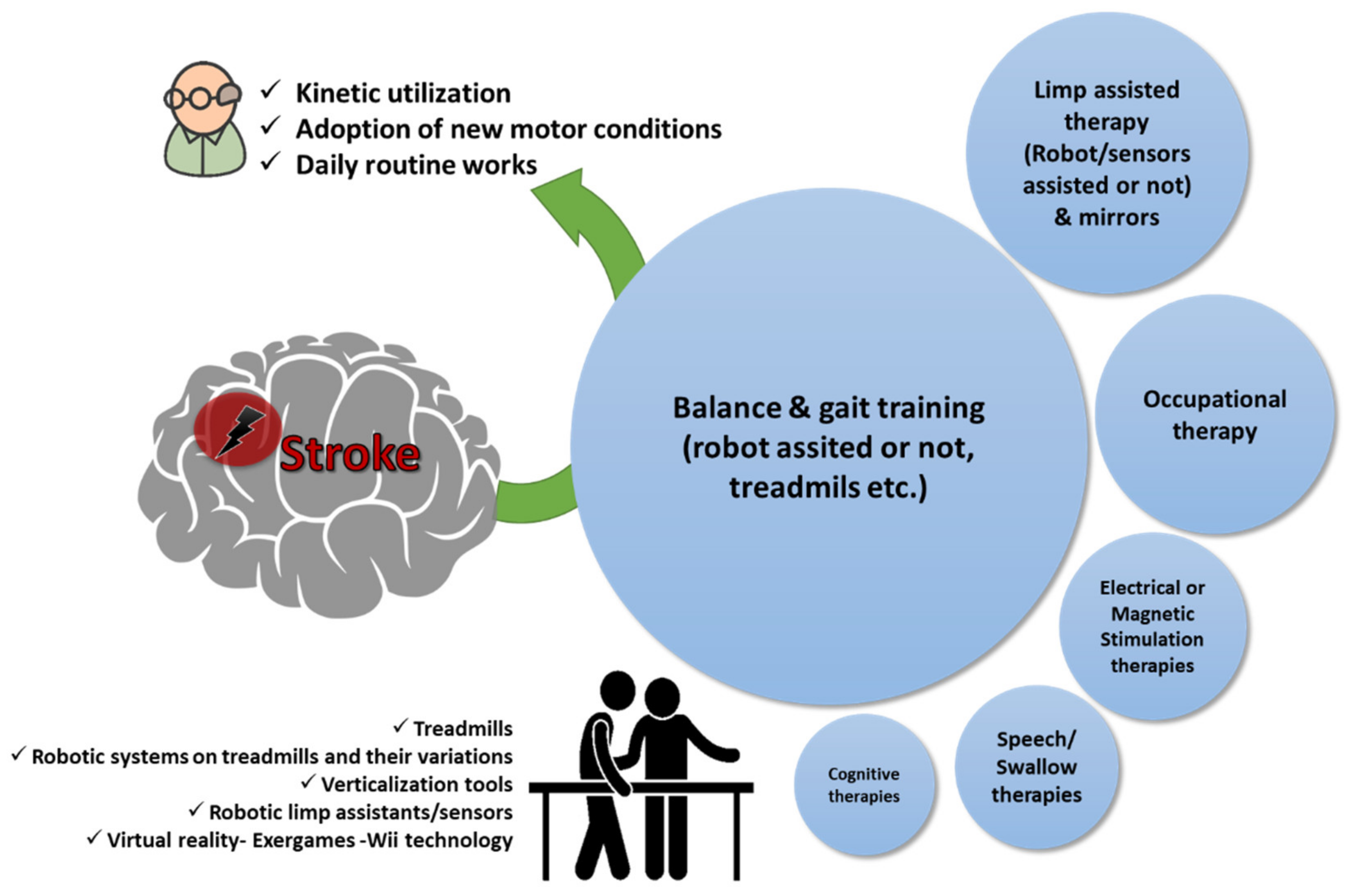

The main rehabilitation goals using physiotherapy with kinesiotherapy programs at regular intervals in patients recovering from stroke are the kinetic utilization as soon as possible before stiffness and muscle contractions are progressed; educating the patient on how to restore or find alternatives for lost functions (i.e., speech, use of one hand to dress up, etc.), as well as constant care and support towards adoption of new motor conditions that will assist the patient to accept the current status and return to their daily routine as much as possible (

Figure 1). Physiotherapy sessions after stroke are a continuous healthcare process and there are cases such as intensive therapy sessions for sensory and motor stimulation that are evaluated even for chronic stroke patients for improving function and use of the affected limb in their daily activities

[17][1].

Figure 1. Physiotherapy goals in patients with stroke. A qualitative infographic of clinical trials in the literature regarding physiotherapy approaches in elders recovering from stroke with the incorporation of several pieces of state-of-the-art equipment.

Body-weight-supported treadmill rehabilitation for balance and gait training (robot-assisted or not) is the most often-used physiotherapy technique for restoring motor function after a stroke in elders

[18,19,20,21,22][2][3][4][5][6]. Generally, treadmill training with body-weight support seems to lead to better walking and postural results than gait training with no body-weight support and overground walking

[23,24][7][8]. Regardless of the method applied, gait trainers or floor walking exercises early after stroke assist to restore gait function

[23][7]. A typical intervention includes a 6- or 10-min walking test for evaluation of speed and endurance, respectively. Additionally, for balance, functionality, and quality of life, evaluation tests such as those of the functional independence measure, Tinetti scale, and Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) are often employed

[25,26][9][10]. Alternate approaches after stroke are trying to assess the speed and distance to gait or mobility interventions with combinations of occupational therapy that try to establish sessions that can be followed even when at home

[27,28,29][11][12][13].

Walking on treadmills and interventions for recovery of limb function (e.g., arms, legs, ankles, etc.) with the incorporation of mirrors to improve visual-spatial ability for treating hand disabilities or other ergometric tools or stimulation techniques seem to be beneficial when added in conventional rehabilitation programs, and their usefulness is related to the level of physical and mental functionality after stroke

[30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. Robotic arms or ergometers have been found to be effective tools for rehabilitation

[31,35,41][15][19][25], while for feet, there are several approaches of foot sensors to measure the ankle’s flexion and extension motions with mixed results till today

[42,43,44][26][27][28]. Other approaches, such as constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), may reflect improvements in functionality for patients with stroke, but as the authors point out, additional data are needed to better describe and relate changes with underlying mechanisms

[45][29]. Generally, CIMT approaches were difficult to follow in terms of the patient’s compliance and the physiotherapist’s willingness to exploit them

[46,47][30][31]. Repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation seems to improve frequency of motor-evoked potentials, muscle function (torque about elbow), and purposeful movement when applied early after stroke

[48][32]. In addition, electrical stimulation, and exercise for swallow post-stroke showed promising results for patients suffering from stroke and cricopharyngeal muscle dysfunction, as well as appearing to improve functionality regarding hand grip and maybe strength of the arms or leg muscles

[49,50,51,52,53,54][33][34][35][36][37][38]. In other studies, it is suggested that early modulation of perilesional oscillation coherence seems a better strategy for brain stimulation interventions

[55][39].

Treadmills with several add-ons including virtual reality (omnidirectional treadmills) and robotic parts are often applied in elderly patients recovering from stroke as a walking rehabilitation program to improve physical function for affected body areas (e.g., shoulder and arms) and enhance as much as possible their neuroplasticity

[19,56,57,58,59,60,61,62][3][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]. In this respect, till today, several randomized clinical trials tried to evaluate the walking abilities using numerous approaches and exercises on treadmills, with also the application of obstacle crossing or other cognitive distractions, to evaluate their usability as adjuvant therapies in improving walking rehabilitation among people with stroke

[18,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72][2][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56]. Thus far, the results from these trials suggest that for patients with stroke, retraining gait with the use of a treadmill and a percentage of their body weight supported (e.g., Lokomat

® robotic assistive device) or assisted through several wearables, resulted in improved postural abilities over those with no support on their body weight

[18,24,36,41,44,71,73,74,75,76][2][8][20][25][28][55][57][58][59][60]. Variations of the intensity (e.g., speed) or of the type of the exercises (e.g., obstacles-crossing training or cognitive distractions) and the virtual reality environment or incorporation of exergames seems to be also beneficial on patients’ balance, upper limb motor function, and generally in cognitive and functional outcomes in patients recovering from stroke

[19,42,70,72,77,78,79,80][3][26][54][56][61][62][63][64]. Furthermore, the incorporation of treadmill and aerobic exercises as an early intervention seems to benefit patients with stroke, except for cases with large and right-sided lesions; however, additional data are needed

[18,77,81,82][2][61][65][66]. Treadmills seem also to be inferior to other approaches such as dance lessons (tango, etc.)

[83][67]. Finally, utilization of computer-based rehabilitation games (i.e., Wii Sports

TM, Nintendo Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) may provide new, flexible, and easy to use (even from home) forms of rehabilitation for improving speed and working memory for patients after stroke

[84,85][68][69].

2. Parkinson’s Disease

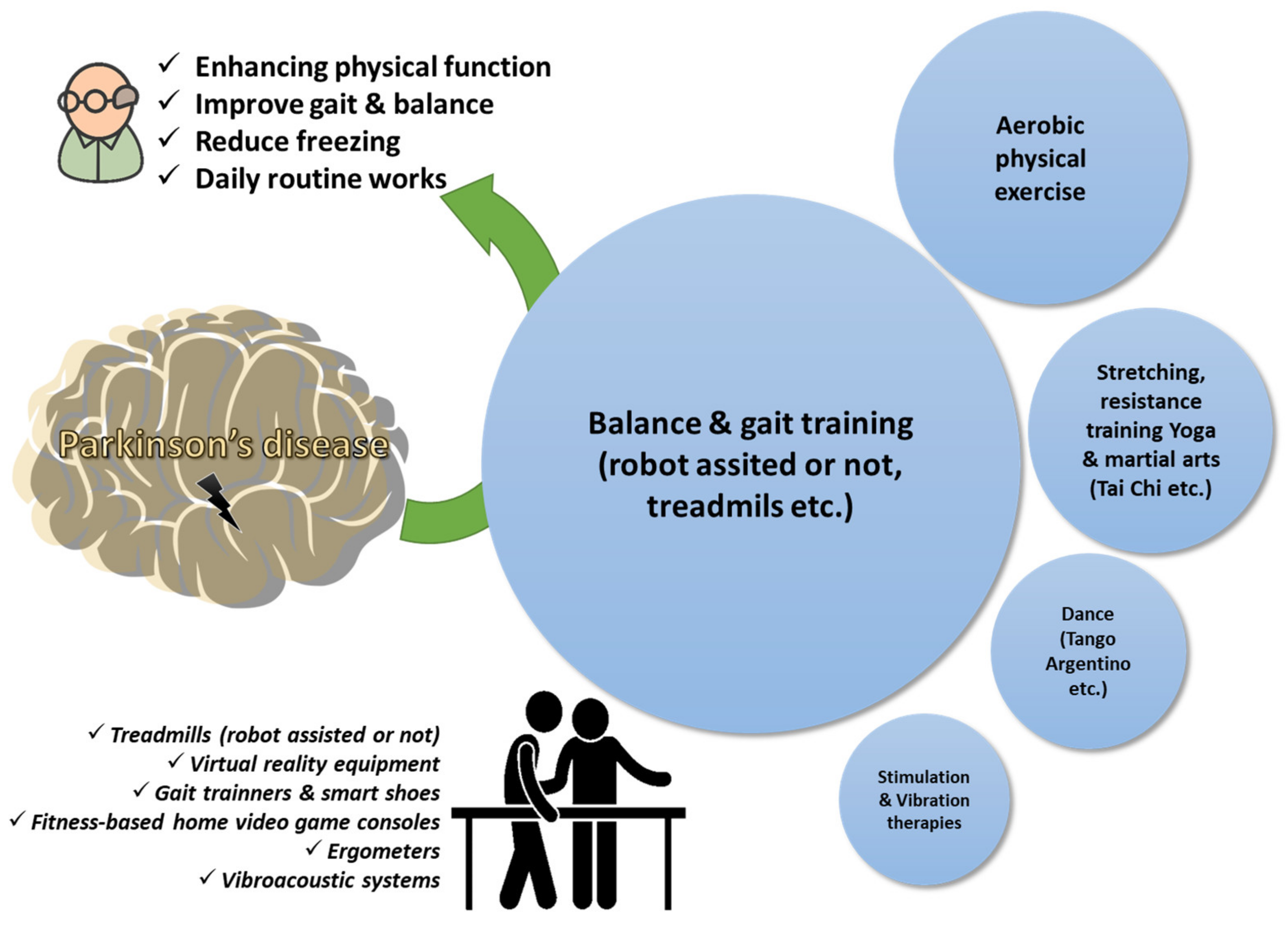

In Parkinson’s disease, enhancing physical function and well-being, thus improving patients’ quality of life, is essential to address the dysfunctions as the disease is progressing

[86,87,88][70][71][72]. Physiotherapy goals in Parkinson’s disease are related with maintaining, correcting, and/or improving functional ability, strength, flexibility, posture, and balance, and thus improving daily activities, breathing, and relaxation, and reducing freezing moments that may cause falls and injuries (

Table 21)

[89,90][73][74]. Thus far, there are several studies of non-pharmacological physiotherapy interventions among older adults usually between 60 and 80 years old with Parkinson’s disease, often accompanied with robot assistance or virtual reality tools, that have been evaluated as interventions to enhance walking and physical performance even for home sessions

[91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83]. These procedures include a wide range of approaches, focusing on posture, upper extremity function, balance, and gait combined with the use of cognitive movement and exercise strategies to maintain and improve quality of life.

Raccagni et al. (2019) studied the impact of physiotherapy on improving motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease, incorporating strength, flexibility, posture, and balance exercises, walking and coordination training, swing exercises, double work, and climbing stairs, which showed that patients’ gait improved significantly

[100][84]. Follet et al. (2010) used two different brain stimulation methods to achieve improved motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease observing the same improvement with both methods

[101][85]. Barboza et al. (2019), studying the effects of physiotherapy and cognitive education in patients with Parkinson’s disease, concluded that both methods, either individually or in combination, have a positive effect on patients in the outcome of the disease

[102][86]. GAITRite

® combined with a closed-loop visual–auditory walker that could be applied at the patient’s home appeared to be effective in improving gait and decreasing freezing, and thus enhancing functional mobility and quality of life

[95][79]. GAITRite

® has also been applied to examine the impact of an obstacle’s height for elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease, revealing similar strategies in walking over tall obstacles that could be further utilized in physiotherapy sessions

[97][81]. Robot-assisted gait training such as Gait Trainer GT1 have been demonstrated to improve factors of balance (Berg’s Balance Scale) and reaction to an unexpected shoulder pull (Nutt’s rating)

[91,92,93,103][75][76][77][87]. Other effective methods of physiotherapy to improve gait that have been tested are vibration therapy

[104][88] and spinal cord stimulation

[105][89]. Studies on vibration therapies—despite being proposed since the 19th century—have not managed to produce sufficient evidence with possible placebo-related factors to contribute to motor function for patients with Parkinson’s disease

[104][88]. Pallidal or subthalamic stimulation as well as spinal cord stimulation resulted in improvements in motor function for Parkinson’s disease patients

[101,105][85][89]. High intensity aerobic exercise seems to help as a feasible and safe intervention in rehabilitation of those patients mainly for sleep outcomes

[106,107,108][90][91][92]. On the other hand, interventions for rehabilitation with embedded mental practice did not show any significant difference when compared with relaxation during rehabilitation

[109][93].

In addition to physical exercises, alternative approaches have been employed to investigate whether similar results can be achieved, such as yoga, dance (especially tango), tai chi, and qigong

[110,111,112,113,114][94][95][96][97][98]. Kwok et al. (2019)

[110][94] studied the effectiveness of mindfulness yoga in relation to stretching and resistance exercises in patients with NP. They concluded that yoga is just as effective as stretching and resistance exercises in improving motor dysfunction and mobility, as well as reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms that are often present in Parkinson’s disease patients. In other cases, however, although patients’ expectations were high, the results were not encouraging. Music-contingent gait training is feasible

[115][99], while tango dance did not show any positive feedback thus far

[83,116][67][100].

Regarding state-of-the-art equipment, treadmill training is often combined with a virtual reality environment to assess physical performance. The GAITRite

® portable walking system seems to be the equipment of choice in most studies to measure temporal and spatial parameters for gait styles

[92,95,97,117][76][79][81][101]. The results seem to point out that virtual interactive environments or visual cues are beneficial for people suffering from Parkinson’s disease

[94,118,119,120][78][102][103][104]. Mirelman et al. (2011)

[94][78] employed a progressive intensive program combining a treadmill with virtual reality equipment to evaluate walking under normal or dual-task conditions or during managing physical obstacles. Cognitive function and functional performance were also assessed with participants to process multiple stimuli simultaneously and make decisions about the various obstacles on two levels while continuing to walk down the aisle. The results showed that the combination of the treadmill with the virtual reality system can be feasible in the physiotherapy of patients with Parkinson’s disease, enhancing physical performance, gait during complex challenging conditions, and aspects of cognitive function. In clinical trials from the group of Picelli et al., the robotic pacing training using the Gait Trainer GT1 further improved the gait aspects compared to physiotherapy with active joint mobilization with a moderate amount of conventional gait training, which had also positive results but at a lower level

[91,92][75][76]. Other studies are also reporting similar findings when incorporating physiotherapy alone or with cognitive training

[100,102,103][84][86][87]. These findings have important implications for understanding motor learning in the presence of disease and for treating the risk of falling of Parkinson’s disease patients and their overall quality of life (

Figure 2).

Figure 2. Physiotherapy goals in Parkinson’s disease. A qualitative infographic of clinical trials in the literature regarding physiotherapy approaches in elders managing Parkinson’s disease with the incorporation of several pieces of state-of-the-art equipment.

3. Age-Related Cognitive Impairment

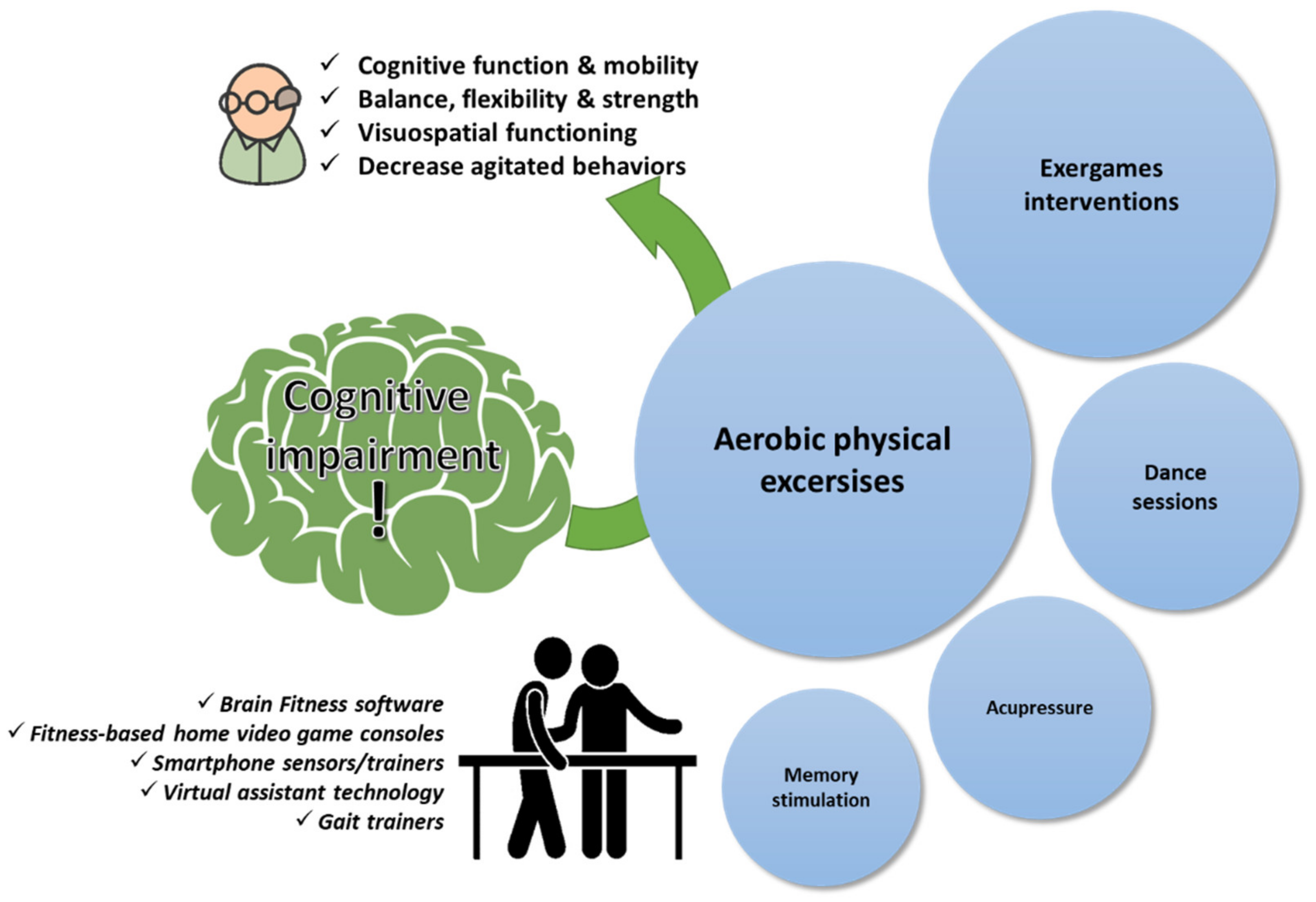

Physiotherapy in the elderly with age-related cognitive impairment is not explored as much as in cases of stroke and Parkinson’s disease (

Table 32). This can be attributed to several factors including the obscureness in diagnostic criteria to separate the condition from Alzheimer’s disease or the often reluctance from elderly people to seek medical advice, considering it an expected impact of the aging process

[121,122][105][106]. However, a well-known fact is that physical exercise such as aerobic fitness or other exercises enhance cognitive function and neuropsychiatric symptoms for people with cognitive decline, thus preventing functional decline of the brain, which is a natural consequence of the aging of the body (

Figure 3)

[123,124,125][107][108][109]. Interestingly, several spatial, temporal, and spatiotemporal gait parameters (i.e., gait speed) have been suggested to be a potential subclinical marker of cognitive impairment

[126][110]. Hence, it has been shown through several studies that patients with cognitive impairment seem to benefit from interventions that incorporate physical exercise (e.g., aerobic exercises), stationary bikes with video screens, or exergames

[125,127][109][111]. Especially for patients at risk, combined physical and cognitive training shows indices of a positive neuroplastic effect in mild cognitive impaired patients

[127][111]. In cognitive frailty, physiotherapy interventions with resistance exercise training approaches are effective in improving cognitive function and physical performance in the elderly with cognitive frailty

[128][112]. Resistance exercises (training exercises) are effective in improving mental function and physical condition in the elderly with cognitive impairment, especially episodic memory and processing speed. Furthermore, the incorporation of exercise programs that are delivered remotely through smartphones revealed promising data regarding the advantages of remote fitness applications for delivering customized exercise programs for adults aged >65 years

[129][113]. The utilization of smartphone technologies and virtual assistant technologies (i.e., iPad, Alexa) to deliver customized multicomponent exercise programs for older adults is continuously evaluated with promising evidence from short-term perspectives or larger randomized trials

[130,131,132,133,134][114][115][116][117][118].

Figure 3. Physiotherapy goals in age-related cognitive impairment. A qualitative infographic of clinical trials in the literature regarding physiotherapy approaches in elders managing cognitive impairment with the incorporation of several pieces of state-of-the-art equipment.

In addition to the exercise interventions, the incorporation of music and dance lessons appear to be beneficial in mild cognitive cases

[135[119][120],

136], whereas alternative approaches such as Tao-based techniques, although very promising in theory for improving cognitive ability, ultimately did not have the expected results in improving cognition or physical mobility

[117][101]. On the other hand, yoga as a low-risk intervention has showed some preliminary evidence of a feasible intervention that improves visuospatial functioning in patients with mild cognitive impairment

[137][121]. Finally, there are reports that acupressure and Montessori-based activities could have a positive impact and be beneficial for these patients, especially for soothing and reducing anxiety in people with cognitive impairment

[138][122].