Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Bartosz Szmyd and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Intramedullary spinal cord abscesses (ISCA) are rare. Typical symptoms include signs of infection and neurological deficits. Symptoms among (younger) children can be highly uncharacteristic. Therefore, prompt and proper diagnoses may be difficult. Typical therapeutic options include antibiotics and neurosurgical exploration and drainage.

- intramedullary spinal cord abscess

- ISCA

- abscess

- spinal cord tumor

1. Introduction

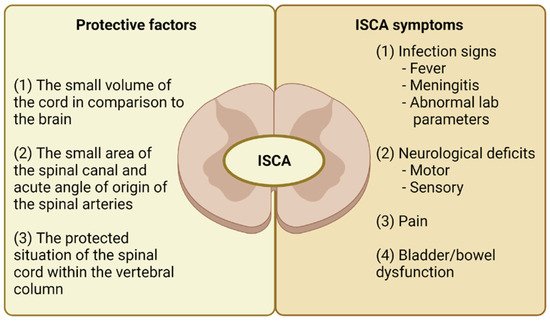

The intramedullary spinal cord abscesses (ISCAs) remain a rare, albeit widely publicized entity since the first reported case in 1830 [1][2][3]. Their rarity may be explained by the following factors: (1) the small volume of the spinal cord compared to the brain, (2) the small area of the spinal canal and acute angle of origin of the spinal arteries, and (3) the protected condition of the cord within the vertebral canal (see Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1. The protective factors and typical symptoms of intramedullary spinal cord abscess. Legend: ISCA — intramedullary spinal cord abscess.

The typical symptoms include infection signs (fever/meningitis), neurological deficits (motor and/or sensory), and also pain (see Figure 1). These symptoms among children, especially younger ones, can be highly uncharacteristic and regrettably, can be associated with significant mortality. Therefore, a rapid and proper diagnosis may be difficult. Typical therapeutic options include antibiotics and neurosurgical exploration and drainage [4].

2. What Is Currently Known about Intramedullary Spinal Cord Abscesses in Children?

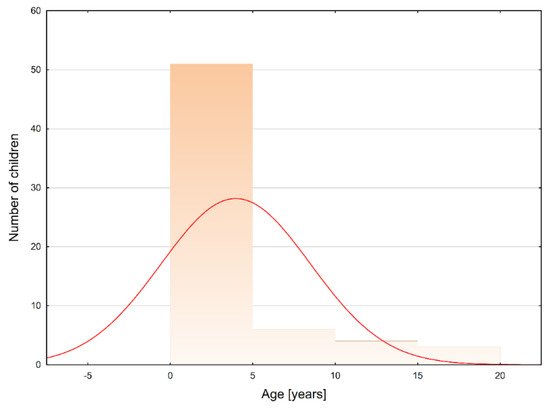

This diagnosis of ISCA was confirmed in 37 (57.81%) boys and 25 (39.06%) girls. In two cases (3.13%), there were no data regarding sex. The analyzed ages did not reveal a normal distribution (Shapiro–Wilk test; p < 0.001; see Figure 2). The median age of the patients was 2.00 years (IQR: 1.17–5.00). Boys were significantly older than girls: 3.60 (IQR: 1.42–6.00) vs. 1.33 (IQR: 1.00–2.25; p = 0.007).

Figure 2. The age distribution among pediatric patients who developed intramedullary spinal cord abscesses (Shapiro−Wilk test: p < 0.001). Legend: red curve − expected normal distribution.

2.1. ISCA Course and Localization

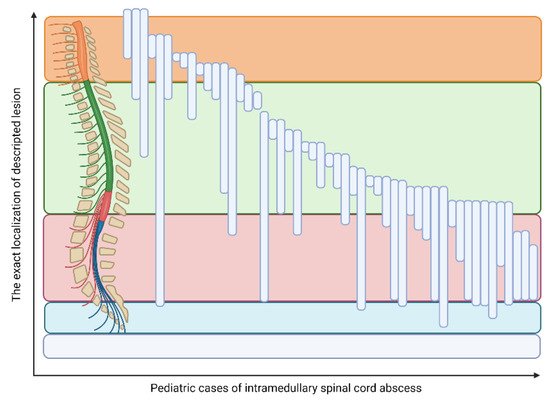

The course of ISCA can be divided into acute (<1 week), subacute (1–6 weeks), and chronic (>6 weeks) [5]. The most frequently observed manifestation was acute: 25 (39.06%) followed by 21 (32.81%) subacute cases. Chronic onset was observed in 13 (20.31%) cases. In five (7.82%) cases there were no detailed data. Neither sex (p = 0.350) nor age (R = −0.010, p = 0.940) affected the onset of ISCA. The exact location was identified in 60 cases (including seven holocords and two isolated lesions in the conus medullaris). The location of ISCA lesions in the remaining 51 cases is shown in Figure 3. The precise localization was not directly provided in four of the cases. In the newborn/infant group the spinal cord terminated most frequently at the level of L2/L3. As we age, the level of spinal cord termination is changing, and in the adolescent population, it was most often found at the level of the middle third of L1 and L1/L2 [6]. Therefore, it seems to be interesting that in 16 (25%) cases the abscess was observed below the L3 level. The possible reasons for these observations were found in 12 (75%) cases. There were distinguished the following causes: five (31.25%) cases of spina bifida, four (25.0%) cases of (possible) coexistence of ISCA and intradural extramedullary lesion, two (12.5%) cases of low conus medullaris. Moreover, reswearchers identified one case of the following explanation: retained medullary cord [6], tethered cord [7], and mild thoracolumbar scoliosis with upper anal cleft [8]. Theoretically, the classification of the lesion within the terminal filum may be the next issue. Lesions in this localization are considered intraspinal, which may be in contradiction to the aforementioned end of the spinal cord.

Figure 3. The localization of the intramedullary spinal cord abscess in children.

2.2. Symptoms Present in ISCA Patients

Laboratory results indicative of inflammation/infection were identified in 55 (85.94%) patients. These included fever—39 (60.94%), abnormalities in laboratory tests (elevated white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein concentration, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate)—34 (53.13%), and symptoms of meningitis—12 (18.75%). Motor deficits were observed in 57 (89.06%) patients. In the other cases, the following symptoms were noted, e.g., irritability, exaggerated lower and upper limb reflexes, and isolated fevers. Sensory deficits were noted in 25 (39.06%) patients. Moreover, urinary and bowel dysfunction were observed in 28 (43.75%) and 11 (17.19%) cases, respectively.2.3. Predisposing Factors and Comorbidities

2.3.1. Dermal Sinus Tracts

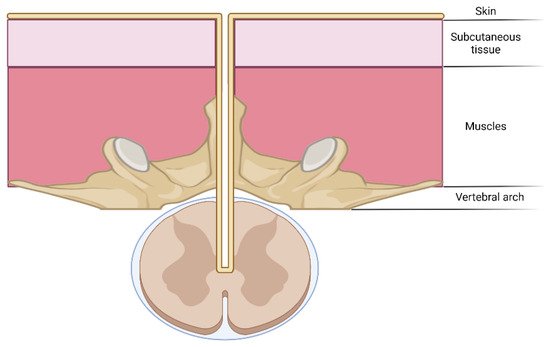

Congenital midline defects, as well as anatomic abnormalities of the spinal cord or vertebral column, are some of the key predisposing factors for ISCA. One of these is dermal sinus tracts (see Figure 4), an abnormality present at birth over the dorsal midline where an abnormal epithelialized connection from the skin tracks inwards toward the spine, especially in the lumbar (32–43%) and the lumbosacral regions (32–54%) [9]. Their prevalence is estimated at 1 in 2500 live births.

Figure 4. The schematic representation of a dermal tract as a predisposing factor for intramedullary spinal cord abscesses.

2.3.2. (Epi)dermoid Cyst

Epidermoid and dermoid cysts are two major variants of ectodermal-derived neural axis cysts [11]. Here rwesearchers found three cases of this condition in ISCA patients [11][12][13]. Interestingly, these pathological entities can be related to a dermal sinus tract it is not mandatory [11].2.3.3. Spina Bifida

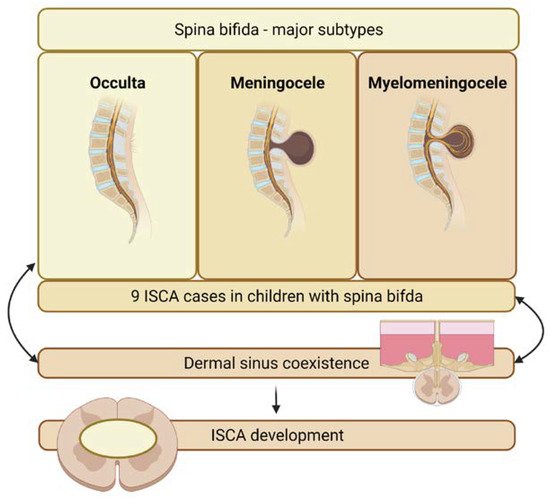

RWesearchers identified nine cases of ISCA related to spina bifida (see Figure 5) [7][12][14][15][16][17][18][19]. In almost all of these cases, the presence of dermal sinus tracts was noted. Therefore, it should be assumed, that the true predisposing factor, dermal sinus tracts, is more frequently observed among patients with abnormalities of the ectodermal, mesenchymal, or neural crest derivatives such as myelomeningocele, lipomylomeningocele, and other forms of spina bifida occulta [15]. Perhaps a similar explanation can be given in the case of ISCA among adult patients born with talipes equinovarus [20][21].

Figure 5. Relationship between spina bifida and intramedullary spinal cord abscess.

2.3.4. Prior Inflammation

Prior inflammation is a risk factor for developing ISCA. It may lead to a hematogenous or contagious spread of infection. The following scenarios were observed: general infection [22][23], respiratory system infection [24], maxillary sinus abscesses [25], Brucella infection [26], and long-term diarrhea [27]. Interestingly, there were noted some cases of previous tuberculosis [25].2.3.5. Others

Other risk factors included iatrogenic ones as well as trauma. In theour literature search, researcherswe have identified one case of ISCA which developed in the course of multiple attempts to perform a lumbar puncture and a second one due to spinal cord injury [28][29].References

- Brian Hood; Stacey Wolfe; Rikin A. Trivedi; Chetan Rajadhyaksha; Barth Green; Intramedullary Abscess of the Cervical Spinal Cord in an Otherwise Healthy Man. World Neurosurgery 2011, 76, 361.e15-361.e19, 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.01.013.

- Manimaran D; Encysted Spermatic Cord Hydrocele in a 60-year-old, Mimicking Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia: A Case Report. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH 2014, 8, 153-4, 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6998.4039.

- John Foley; INTRAMEDULLARY ABSCESS OF THE SPINAL CORD. The Lancet 1949, 254, 193-195, 10.1016/s0140-6736(49)91194-0.

- Christopher T. Chan; Wayne L. Gold; Intramedullary Abscess of the Spinal Cord in the Antibiotic Era: Clinical Features, Microbial Etiologies, Trends in Pathogenesis, and Outcomes. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1998, 27, 619-626, 10.1086/514699.

- Paulo Sergio Lucas da Silva; Rafael Duarte De Souza Loduca; Intramedullary spinal cord abscess as complication of lumbar puncture: a case-based update. Child's Nervous System 2013, 29, 1061-1068, 10.1007/s00381-013-2093-9.

- Albert‐Neels Van Schoor; Marius C. Bosman; Adrian T. Bosenberg; Descriptive study of the differences in the level of the conus medullaris in four different age groups. Clinical Anatomy 2015, 28, 638-644, 10.1002/ca.22505.

- X. Morandi; Philippe Mercier; Henri-Dominique Fournier; Gilles Brassier; Dermal sinus and intramedullary spinal cord abscess. Child's Nervous System 1999, 15, 202-207, 10.1007/s003810050370.

- Moh’D. Al Barbarawi; Wadah Khriesat; Suhair Qudsieh; Hanna Qudsieh; Abu Alia Loai; Management of intramedullary spinal cord abscess: experience with four cases, pathophysiology and outcomes. European Spine Journal 2009, 18, 710-717, 10.1007/s00586-009-0885-0.

- Mitchell T Foster; Christopher A Moxon; Elaine Weir; Ajay Sinha; Dermal sinus tracts. BMJ 2019, 366, l5202, 10.1136/bmj.l5202.

- Raj S. Chandran; Rajmohan Bhanuprabhakar; Sivakumar Sumukhan; Intramedullary Spinal Cord Abscess: Illustration of Two Cases and Review of Literature. Indian Journal of Neurosurgery 2017, 06, 031-035, 10.1055/s-0036-1588039.

- Burak Karaaslan; Göktuğ Ülkü; Murat Ucar; Tuğba Bedir Demirdağ; Arda Inan; Alp Özgün Börcek; Intramedullary dermoid cyst infection mimicking holocord tumor: should radical resection be mandatory?—a case report. Child's Nervous System 2016, 32, 2249-2253, 10.1007/s00381-016-3108-0.

- Deborah L. Benzil; Mel H. Epstein; Neville W. Knuckey; Intramedullary Epidermoid Associated with an Intramedullary Spinal Abscess Secondary to a Dermal Sinus. Neurosurgery 1992, 30, 118-120, 10.1227/00006123-199201000-00022.

- F. Çokça; O. Meço; E. Arasil; A. Ünlü; An intramedullary dermoid cyst abscess due toBrucella abortus biotype 3 at T11-L2 spinal levels. Infection 1994, 22, 359-360, 10.1007/bf01715549.

- J M Rogg; D L Benzil; R L Haas; N W Knuckey; Intramedullary abscess, an unusual manifestation of a dermal sinus.. AJNR: American Journal of Neuroradiology 1993, 14, 1393-1395.

- Abhisek Chopra; Bijoy Patra; Satinder Aneja; Sharmilla Mukherjee; Anu Maheswari; Anju Seth; Spinal Congenital Dermal Sinus Presenting as a Diagnostic Conundrum. Pediatric Neurosurgery 2012, 48, 187-190, 10.1159/000345595.

- Elham Essa Bukhari; Fawzia Eida Alotibi; Fatal Streptococcus melleri Meningitis Complicating Missed Infected Intramedullary Dermoid Cyst Secondary to Dermal Sinus in a Saudi Child. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 2013, 59, 246-249, 10.1093/tropej/fms073.

- Yoganathan Kanaheswari; CheeHoe Lai; Raja Juanita Raja Lope; Abu Bakar Azizi; Muhamed Annuar Zulfiqar; Intramedullary spinal cord abscess: The result of a missed congenital dermal sinus. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2014, 51, 223-225, 10.1111/jpc.12707.

- Ashok Bhanage; Anand Katkar; Prajakta Ghate; Bhagwant Ratta; Intra-medullary tubercular abscess with spinal dysraphism: An unusual case. Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences 2015, 10, 73-75, 10.4103/1817-1745.154361.

- Rabi Narayan Sahu; Kamlesh Singh Bhaisora; Chaitanya Godbole; Kuntal Kanti Das; Anant Mehrotra; Shardhara Jayesh; Sanjay Behari; Arun Kumar Srivastava; Awadhesh Kumar Jaiswal; Delayed intramedullary abscess in operated case of spinal lipoma. Journal of Pediatric Neurosciences 2016, 11, 234-236, 10.4103/1817-1745.193380.

- R S Maurice-Williams; D Pamphilon; H B Coakham; Intramedullary abscess--a rare complication of spinal dysraphism.. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1980, 43, 1045-1048, 10.1136/jnnp.43.11.1045.

- Carl Hardwidge; Jasbinder PalSingh; Bernard Williams; Pyomyelia: an intramedullary spinal abscess complicating lumbar lipoma with spina bifida. British Journal of Neurosurgery 1993, 7, 419-422, 10.3109/02688699309103498.

- Ahmad Kamgarpour; Mohammad-Ali Izadfar; Ali Razmkon; Neglected intramedullary cord abscess in a 3-year old child: a case report. Child's Nervous System 2007, 24, 153-155, 10.1007/s00381-007-0421-7.

- Nima Baradaran; Hamed Ahmadi; Farideh Nejat; Mostafa El Khashab; Ali Mahdavi; Ali Akbar Rahbarimanesh; Recurrent meningitis caused by cervico-medullary abscess, a rare presentation. Child's Nervous System 2008, 24, 767-771, 10.1007/s00381-008-0593-9.

- J. E. M. Dutton; G. L. Alexander; INTRAMEDULLARY SPINAL ABSCESS. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1954, 17, 303-307, 10.1136/jnnp.17.4.303.

- Jaco Du Plessis; Savvas Andronikou; Salomine Theron; Nicky Wieselthaler; Murray Hayes; Unusual forms of spinal tuberculosis. Child's Nervous System 2007, 24, 453-457, 10.1007/s00381-007-0525-0.

- Mehmet Helvaci; Erhun Kasirga; Nuran Cetin; Isin Yaprak; Intramedullary spinal cord abscess suspected of Brucella infection.. Pediatrics International 2002, 44, 446-448, 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2002.01569.x.

- R.H.M.A. Bartels; Ed G. Gonera; Johannes A. N. Van Der Spek; Henk O. M. Thijssen; Reinier A. Mullaart; Fons J. M. Gabreels; Intramedullary Spinal Cord Abscess- A Case Report. Spine 1995, 20, 1199-1204, 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00017.

- Zelletta Nicola; Calace Antonio; Antonio De Tommasi; Cervical dermal sinus complicated with intramedullary abscess in a child: case report and review of literature. European Spine Journal 2013, 23, 192-196, 10.1007/s00586-013-2930-2.

- Wesley J. Whitson; Perry A. Ball; S. Scott Lollis; Jason D. Balkman; David Bauer; Postoperative Mycoplasma hominis infections after neurosurgical intervention. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics 2014, 14, 212-218, 10.3171/2014.4.peds13547.

More