You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Isidoro Martinez.

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a member of the Hepacivirus genus, Flaviviridae family. HCV is a virus with an envelope and a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome. The HCV genome is translated into a large polyprotein that is processed in three structural (core, E1, E2) and seven non-structural (NS) mature proteins (p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B). A vaccine that only reduces viral titers could be of great help to control the hepatitis C epidemic

- HCV

- vaccine

- adjuvant

- innate immune response

1. Hepatitis C Virus-Host Interaction: The Innate Immune Response

Several hepatic cells may sense HCV infection and contribute to the development of the antiviral immune response. These cells can be divided into two groups: (1) non-immune cells, which include hepatocytes, the main target for HCV replication; (2) professional hepatic immune cells, which include antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as Kupffer cells (KCs) and dendritic cells (DCs), which link the innate immune response and the adaptive immune response. Most of these liver cells are also susceptible to adjuvant stimulation.

1.1. Hepatic Non-Immune Cells

1.1.1. Hepatocytes

Hepatocytes constitute the primary target for HCV replication. Infected hepatocytes recognize viral single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) replication intermediates by the retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I), toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA-5) [23,24][1][2]. Viral recognition activates an intracellular signaling cascade that ends in the phosphorylation of the IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), regulatory factor 7 (IRF7), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), followed by the expression of antiviral and pro-inflammatory genes, mainly IFN type I (IFN-I; IFN-α and IFN-β) and type III (IFN-III; IFN-λ) [25,26,27][3][4][5].

1.1.2. Cholangiocytes

Primary cholangiocytes are not susceptible to HCV infection. However, two cholangiocarcinoma cell lines have recently shown to maintain low HCV replication levels, indicating that cholangiocytes may constitute a new hepatic reservoir [28,29][6][7]. Cholangiocytes can produce inflammatory cytokines after stimulating several TLRs [30][8]. Therefore, cholangiocytes can respond to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from HCV or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from HCV-infected hepatocytes.

1.1.3. Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSCs)

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) do not support efficient HCV replication [31][9]. HSCs express most TLRs producing antiviral cytokines against HCV [32,33,34][10][11][12]. Thus, as with cholangiocytes, HSCs may respond to extracellular PAMPs or DAMPs. TLRs stimulation promotes HSCs differentiation to myofibroblast-like cells (MFLCs)-producing collagen, which drives liver fibrosis. HSCs store dietary retinoids and distribute them to other cells like hepatocytes. IFN stimulated genes (ISGs) expression in hepatocytes depends on retinoids supply, which is impaired after HSCs transformation in MFLCs. Furthermore, HSCs express transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) that may lead to a T-helper cell type 2 (Th2) immune response producing interleukin (IL)-10 and inducting a tolerogenic state in the liver [35][13].

1.1.4. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (LSECs)

HCV mediates a transient productive infection of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) that can sense HCV-PAMPs by RIG-I and TLRs, producing IFN-I and IFN-III [36,37][14][15]. These IFNs promote the release of exosomes that inhibit HCV replication in hepatocytes [36][14]. LSECs are considered an essential link between innate and adaptive immunity by secreting C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10) that attracts activated T-cells to the liver [31,38][9][16]. LSECs can also act as APCs [38][16]. Finally, LSECs capture and transport HCV particles from sinusoid to the space of Disse and secrete bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), which facilitates HCV infection of hepatocytes [36,39,40,41][14][17][18][19].

1.2. Hepatic Professional Immune Cells

1.2.1. Kupffer Cells (KCs)

KCs are resident liver macrophages that regulate tissue homeostasis, immune surveillance, and liver inflammation without being infected by HCV [42,43,44,45,46][20][21][22][23][24]. KCs phagocyte apoptotic bodies, DAMPs, or exosomes from infected cells. In the phagolysosomes, HCV PAMPs are sensed by TLR3/7/8/9. KCs can inhibit HCV replication producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-18, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [47,48,49[25][26][27][28][29][30][31],50,51,52,53], and secreting IFN-β through TLR3/4 signaling pathways [54][32]. In contrast, during chronic infection, KCs promote HCV infection by TNF-α-mediated up-regulation of the HCV receptors occludin and the cluster of differentiation 81 (CD81) [55][33]. KCs also promote a profibrotic function mediated by IL-1β and TNF-α [56,57][34][35]. Moreover, KCs can suppress antiviral functions of T-cells by producing galectin 9 (Gal-9), IL-10, programmed death-ligand (PD-L)-1, PD-L2, and TGF-β [46,49,58,59,60,61][24][27][36][37][38][39].

1.2.2. Natural Killer (NK) Cells

NK cells are the earliest immune responders to HCV infection [62][40], producing IFN-γ, potently suppressing HCV replication, activating macrophages, and promoting T-helper cell type 1 (Th1) responses [63][41]. CD16−CD56bright NK cells produce cytokines to recruit DCs and HCV-specific T-cells without cytolytic functions. CD16−CD56bright cells cause inflammation, but not fibrosis [31,64][9][42]. CD16+CD56dim NK cells are cytolytic (via perforin and granzyme), secrete low levels of cytokines, and induce fibrosis development [31,65][9][43]. Thus, both cytolytic and non-cytolytic functions of NK cells reduce the HCV viral load [66,67,68,69,70][44][45][46][47][48]. However, NK cells can also have a detrimental role against HCV infection by killing DCs and activated T-cells [71,72,73][49][50][51]. NKT cells are another group of NK cells that play a crucial role in the immune response against HCV by modifying the Th1/Th2 balance [74][52].

1.2.3. Dendritic Cells (DCs)

DCs are a heterogeneous population that comprises classical or myeloid DCs (mDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). The primary role of mDCs is to present antigens to T-cells to induce immunity or tolerance [75[53][54],76], while pDCs produce high IFNs levels and other cytokines with immunostimulatory properties [77,78,79][55][56][57]. In the liver, DCs are susceptible to low levels of HCV infection [80][58]. DCs are activated through TLR3/7/8 recognition of HCV RNA to produce IL-12, IL-18, and IL-27, which support Th1 development and IFN-γ secretion [81][59]. On the other hand, HCV structural (core, and HCV envelope glycoprotein E1 and E2) and NS (i.e., NS3) proteins activate TLR2 on DCs, impairing its functionality [82,83,84][60][61][62].

2. Innate Immune Response and Vaccine Adjuvants

From a historical point of view, vaccines are the most cost-effective and successful measures against viral infections. Although live-attenuated vaccines are usually highly immunogenic, there are some concerns regarding their stability and safety. Therefore, modern vaccines focus on non-living antigens, such as recombinant proteins, peptides, or DNA. However, these vaccines are poorly immunogenic and need the co-administration of adjuvants to increase their efficacy.

Adjuvants have been used in human vaccines for decades. However, the mechanisms of action of these classical general adjuvants remain incompletely understood [85][63]. Recent advances in the innate immunity knowledge and its link with adaptive immunity has allowed the development of new adjuvants that activate specific immunological pathways [86,87][64][65].

2.1. Innate Immunity Is Linked to Adaptive Immunity

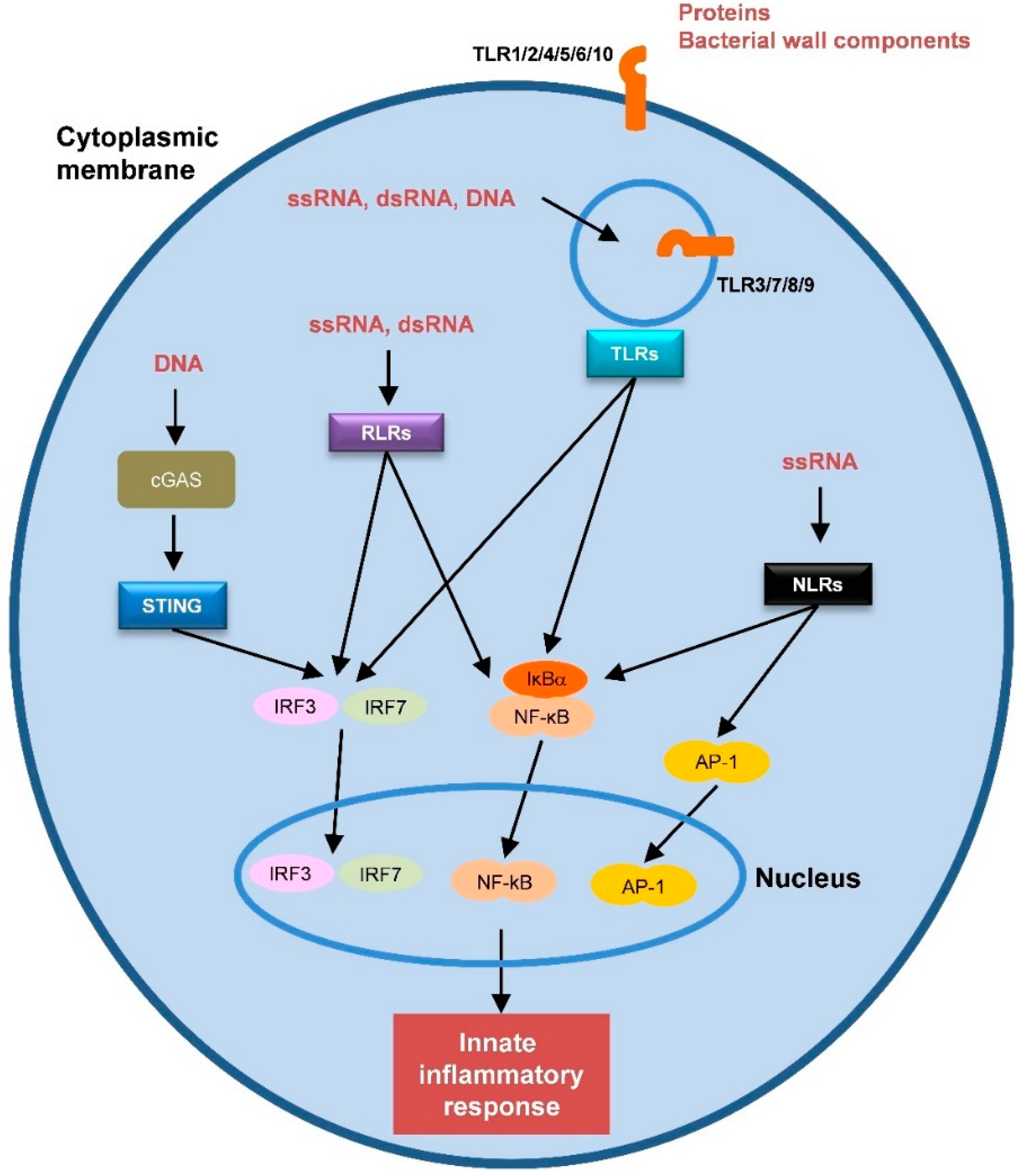

The innate immune response against viruses is initiated by the recognition of PAMPs (viral proteins and nucleic acids) by cellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (Figure 1). DAMPs are molecules released by damaged or dying cells that also trigger the innate immune response. Activation of the innate response promotes adaptive immunity. APCs, particularly DCs, play a prominent role in this process [88][66]. DCs are well-equipped with several PRRs that recognize a variety of PAMPs, triggering intracellular pathways and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Moreover, this recognition enhances the ability of DCs to present antigens and travel to lymphoid tissues where they interact with T- and B-lymphocytes to induce and modulate the adaptive immune response [89][67]. Therefore, PRRs stimulation by adjuvants could have a profound impact on vaccine performance [87,90,91][65][68][69].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the different pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and their natural ligands. Transcription factors that are activated by the PRRs are also represented.

2.2. Innate Immunity-Based Adjuvants

Several PRRs have been identified in humans, including TLRs, RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) and cytosolic DNA sensors (CDs) (Figure 1) [88][66]. Most of the current innate immunity-based adjuvants target TLRs. In the following sections, we will describe sSome of the most relevant adjuvants targeting PRRs (s is described in Table 1).

Table 1.

List of innate immunity-based adjuvants targeting pattern recognition receptors (PRRs).

| PRR Type | Class of Activated Innate Receptor/Pathway | Adjuvant Name | Composition | Main Stimulated Immune Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLRs | TLR3 | Poly(I:C) or Poly(I:C) stabilized with poly-L-lysine | dsRNA analogs | Ab response, CD8+ T-cell response, Th1 type immunity |

| TLR4 | MPLA, GLA-SE, RC-529 | MPL GLA AGP | Ab response CD8+ T-cell response Th1 type immunity | |

| TLR5 | Flagellin fused to antigen | Bacterial flagellin | Ab response, Th1/Th2 response | |

| TLR7, 8 or both | Imiquimod/R837 (TLR7), Resiquimod/R848 (TLR7/8), 3M-052 (TLR7/8) | Imidazoquinoline analogs | Ab response, CD4+/CD8+ T-cell response, Th1 type immunity | |

| TLR9 | CpG-ODN | Synthetic ODN with optimized CpG motifs | Ab response, CD8+ T-cell response, Th1 type immunity | |

| NLRs | RIG-I MDA-5 | M8, Defective interfering RNA | dsRNA analogs | Ab response, CD4+/CD8+ T-cell response |

| RLRs | Nod1 Nod2 | iE-DAP, MDP | Bacterial peptidoglycan analogs | Ab response |

| CDs | STING | c-di-GAMP | Bacterial cyclic dinucleotides | Ab response, CD8+ T-cell response, Th1 type immunity |

Ab: Antibody; AGP: Aminoalkyl glucosaminide 4-phosphate; c-di-GAMP: Cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate dinucleotide; CDs: Cytosolic DNA sensor ligands; CpG: Cytosine-phosphate-guanine; dsRNA: Double-stranded RNA; GLA: Glucopyranosyl lipid-adjuvant; iE-DAP: γ-D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid; MDA-5: Melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; MDP: Muramyl dipeptide; MPLA: Monophosphoryl lipid A adjuvant; NLRs: Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors; Nod1/2: Nucleotide oligomerization domain 1/domain 2; ODN: Oligodeoxynucleotide; Poly(I:C): Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid; PRRs: Pattern recognition receptors; RIG-I: Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I; RLRs: RIG-I-like receptors; STING: Stimulator of interferon genes; Th1/Th2: T-helper cell type 1/type 2; TLRs: Toll-like receptors.

References

- Saito, T.; Owen, D.M.; Jiang, F.; Marcotrigiano, J.; Gale, M., Jr. Innate immunity induced by composition-dependent RIG-I recognition of hepatitis C virus RNA. Nature 2008, 454, 523–527.

- Cao, X.; Ding, Q.; Lu, J.; Tao, W.; Huang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, J.; Liu, Y.J.; Zhong, J. MDA5 plays a critical role in interferon response during hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 771–778.

- Thomas, E.; Gonzalez, V.D.; Li, Q.; Modi, A.A.; Chen, W.; Noureddin, M.; Rotman, Y.; Liang, T.J. HCV infection induces a unique hepatic innate immune response associated with robust production of type III interferons. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 978–988.

- Israelow, B.; Narbus, C.M.; Sourisseau, M.; Evans, M.J. HepG2 cells mount an effective antiviral interferon-lambda based innate immune response to hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1170–1179.

- Dickensheets, H.; Sheikh, F.; Park, O.; Gao, B.; Donnelly, R.P. Interferon-lambda (IFN-lambda) induces signal transduction and gene expression in human hepatocytes, but not in lymphocytes or monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 93, 377–385.

- Fletcher, N.F.; Humphreys, E.; Jennings, E.; Osburn, W.; Lissauer, S.; Wilson, G.K.; van, I.S.C.D.; Baumert, T.F.; Balfe, P.; Afford, S.; et al. Hepatitis C virus infection of cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1380–1388.

- Navas, M.C.; Glaser, S.; Dhruv, H.; Celinski, S.; Alpini, G.; Meng, F. Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Cholangiocarcinoma: An Insight into Epidemiologic Evidences and Hypothetical Mechanisms of Oncogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1122–1132.

- Syal, G.; Fausther, M.; Dranoff, J.A. Advances in cholangiocyte immunobiology. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver. Physiol. 2012, 303, G1077–G1086.

- Kaplan, D.E. Immunopathogenesis of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 44, 735–760.

- Seki, E.; Brenner, D.A. Toll-like receptors and adaptor molecules in liver disease: Update. Hepatology 2008, 48, 322–335.

- Florimond, A.; Chouteau, P.; Bruscella, P.; Le Seyec, J.; Merour, E.; Ahnou, N.; Mallat, A.; Lotersztajn, S.; Pawlotsky, J.M. Human hepatic stellate cells are not permissive for hepatitis C virus entry and replication. Gut 2015, 64, 957–965.

- Wang, B.; Trippler, M.; Pei, R.; Lu, M.; Broering, R.; Gerken, G.; Schlaak, J.F. Toll-like receptor activated human and murine hepatic stellate cells are potent regulators of hepatitis C virus replication. J. Hepatol. 2009, 51, 1037–1045.

- Lau, A.H.; Thomson, A.W. Dendritic cells and immune regulation in the liver. Gut 2003, 52, 307–314.

- Giugliano, S.; Kriss, M.; Golden-Mason, L.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Stone, A.E.; Soto-Gutierrez, A.; Mitchell, A.; Khetani, S.R.; Yamane, D.; Stoddard, M.; et al. Hepatitis C virus infection induces autocrine interferon signaling by human liver endothelial cells and release of exosomes, which inhibits viral replication. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 392–402.e313.

- Wu, J.; Meng, Z.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, E.; Trippler, M.; Broering, R.; Bucchi, A.; Krux, F.; Dittmer, U.; Yang, D.; et al. Toll-like receptor-induced innate immune responses in non-parenchymal liver cells are cell type-specific. Immunology 2010, 129, 363–374.

- Kern, M.; Popov, A.; Scholz, K.; Schumak, B.; Djandji, D.; Limmer, A.; Eggle, D.; Sacher, T.; Zawatzky, R.; Holtappels, R.; et al. Virally infected mouse liver endothelial cells trigger CD8+ T-cell immunity. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 336–346.

- Gastaminza, P.; Dryden, K.A.; Boyd, B.; Wood, M.R.; Law, M.; Yeager, M.; Chisari, F.V. Ultrastructural and biophysical characterization of hepatitis C virus particles produced in cell culture. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 10999–11009.

- Cormier, E.G.; Durso, R.J.; Tsamis, F.; Boussemart, L.; Manix, C.; Olson, W.C.; Gardner, J.P.; Dragic, T. L-SIGN (CD209L) and DC-SIGN (CD209) mediate transinfection of liver cells by hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14067–14072.

- Rowe, I.A.; Galsinh, S.K.; Wilson, G.K.; Parker, R.; Durant, S.; Lazar, C.; Branza-Nichita, N.; Bicknell, R.; Adams, D.H.; Balfe, P.; et al. Paracrine signals from liver sinusoidal endothelium regulate hepatitis C virus replication. Hepatology 2014, 59, 375–384.

- Crispe, I.N. Liver antigen-presenting cells. J Hepatol. 2011, 54, 357–365.

- Schorey, J.S.; Cheng, Y.; Singh, P.P.; Smith, V.L. Exosomes and other extracellular vesicles in host-pathogen interactions. EMBO. Rep. 2015, 16, 24–43.

- Lavin, Y.; Winter, D.; Blecher-Gonen, R.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Merad, M.; Jung, S.; Amit, I. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell 2014, 159, 1312–1326.

- Ju, C.; Tacke, F. Hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and liver diseases: From pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 316–327.

- Boltjes, A.; Movita, D.; Boonstra, A.; Woltman, A.M. The role of Kupffer cells in hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 660–671.

- Negash, A.A.; Ramos, H.J.; Crochet, N.; Lau, D.T.; Doehle, B.; Papic, N.; Delker, D.A.; Jo, J.; Bertoletti, A.; Hagedorn, C.H.; et al. IL-1beta production through the NLRP3 inflammasome by hepatic macrophages links hepatitis C virus infection with liver inflammation and disease. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003330.

- Shrivastava, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus induces interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta)/IL-18 in circulatory and resident liver macrophages. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 12284–12290.

- Tu, Z.; Pierce, R.H.; Kurtis, J.; Kuroki, Y.; Crispe, I.N.; Orloff, M.S. Hepatitis C virus core protein subverts the antiviral activities of human Kupffer cells. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 305–314.

- Hosomura, N.; Kono, H.; Tsuchiya, M.; Ishii, K.; Ogiku, M.; Matsuda, M.; Fujii, H. HCV-related proteins activate Kupffer cells isolated from human liver tissues. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 1057–1064.

- Zhu, H.; Liu, C. Interleukin-1 inhibits hepatitis C virus subgenomic RNA replication by activation of extracellular regulated kinase pathway. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 5493–5498.

- Zhu, H.; Shang, X.; Terada, N.; Liu, C. STAT3 induces anti-hepatitis C viral activity in liver cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 324, 518–528.

- Sasaki, R.; Devhare, P.B.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus-induced CCL5 secretion from macrophages activates hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 2017, 66, 746–757.

- Broering, R.; Wu, J.; Meng, Z.; Hilgard, P.; Lu, M.; Trippler, M.; Szczeponek, A.; Gerken, G.; Schlaak, J.F. Toll-like receptor-stimulated non-parenchymal liver cells can regulate hepatitis C virus replication. J. Hepatol. 2008, 48, 914–922.

- Fletcher, N.F.; Sutaria, R.; Jo, J.; Barnes, A.; Blahova, M.; Meredith, L.W.; Cosset, F.L.; Curbishley, S.M.; Adams, D.H.; Bertoletti, A.; et al. Activated macrophages promote hepatitis C virus entry in a tumor necrosis factor-dependent manner. Hepatology 2014, 59, 1320–1330.

- Simeonova, P.P.; Gallucci, R.M.; Hulderman, T.; Wilson, R.; Kommineni, C.; Rao, M.; Luster, M.I. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in liver toxicity, inflammation, and fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2001, 177, 112–120.

- Han, Y.P.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Xiong, S.; Garner, W.L.; French, S.W.; Tsukamoto, H. Essential role of matrix metalloproteinases in interleukin-1-induced myofibroblastic activation of hepatic stellate cell in collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 4820–4828.

- Sandler, N.G.; Koh, C.; Roque, A.; Eccleston, J.L.; Siegel, R.B.; Demino, M.; Kleiner, D.E.; Deeks, S.G.; Liang, T.J.; Heller, T.; et al. Host response to translocated microbial products predicts outcomes of patients with HBV or HCV infection. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1220–1230.

- Mengshol, J.A.; Golden-Mason, L.; Arikawa, T.; Smith, M.; Niki, T.; McWilliams, R.; Randall, J.A.; McMahan, R.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Rangachari, M.; et al. A crucial role for Kupffer cell-derived galectin-9 in regulation of T cell immunity in hepatitis C infection. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9504.

- Harwood, N.M.; Golden-Mason, L.; Cheng, L.; Rosen, H.R.; Mengshol, J.A. HCV-infected cells and differentiation increase monocyte immunoregulatory galectin-9 production. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 99, 495–503.

- Nishio, A.; Tatsumi, T.; Nawa, T.; Suda, T.; Yoshioka, T.; Onishi, Y.; Aono, S.; Shigekawa, M.; Hikita, H.; Sakamori, R.; et al. CD14(+) monocyte-derived galectin-9 induces natural killer cell cytotoxicity in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2017, 65, 18–31.

- Nellore, A.; Fishman, J.A. NK cells, innate immunity and hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, 369–377.

- Vivier, E.; Raulet, D.H.; Moretta, A.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Zitvogel, L.; Lanier, L.L.; Yokoyama, W.M.; Ugolini, S. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 2011, 331, 44–49.

- Cooper, M.A.; Fehniger, T.A.; Turner, S.C.; Chen, K.S.; Ghaheri, B.A.; Ghayur, T.; Carson, W.E.; Caligiuri, M.A. Human natural killer cells: A unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56(bright) subset. Blood 2001, 97, 3146–3151.

- Caligiuri, M.A. Human natural killer cells. Blood 2008, 112, 461–469.

- Guidotti, L.G.; Chisari, F.V. Noncytolytic control of viral infections by the innate and adaptive immune response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 65–91.

- Golden-Mason, L.; Rosen, H.R. Natural killer cells: Primary target for hepatitis C virus immune evasion strategies? Liver. Transpl. 2006, 12, 363–372.

- Irshad, M.; Khushboo, I.; Singh, S.; Singh, S. Hepatitis C virus (HCV): A review of immunological aspects. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 27, 497–517.

- Cheent, K.; Khakoo, S.I. Natural killer cells and hepatitis C: Action and reaction. Gut 2011, 60, 268–278.

- Golden-Mason, L.; Rosen, H.R. Natural killer cells: Multifaceted players with key roles in hepatitis C immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 255, 68–81.

- Long, E.O.; Kim, H.S.; Liu, D.; Peterson, M.E.; Rajagopalan, S. Controlling natural killer cell responses: Integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 227–258.

- Maini, M.K.; Peppa, D. NK cells: A double-edged sword in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 57.

- Rehermann, B. Pathogenesis of chronic viral hepatitis: Differential roles of T cells and NK cells. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 859–868.

- Swain, M.G. Hepatic NKT cells: Friend or foe? Clin. Sci. (Lond) 2008, 114, 457–466.

- Merad, M.; Sathe, P.; Helft, J.; Miller, J.; Mortha, A. The dendritic cell lineage: Ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 563–604.

- Steinman, R.M. Decisions about dendritic cells: Past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 1–22.

- Swiecki, M.; Colonna, M. The multifaceted biology of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 471–485.

- Takahashi, K.; Asabe, S.; Wieland, S.; Garaigorta, U.; Gastaminza, P.; Isogawa, M.; Chisari, F.V. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense hepatitis C virus-infected cells, produce interferon, and inhibit infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7431–7436.

- Yoshio, S.; Kanto, T.; Kuroda, S.; Matsubara, T.; Higashitani, K.; Kakita, N.; Ishida, H.; Hiramatsu, N.; Nagano, H.; Sugiyama, M.; et al. Human blood dendritic cell antigen 3 (BDCA3)(+) dendritic cells are a potent producer of interferon-lambda in response to hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1705–1715.

- Marukian, S.; Jones, C.T.; Andrus, L.; Evans, M.J.; Ritola, K.D.; Charles, E.D.; Rice, C.M.; Dustin, L.B. Cell culture-produced hepatitis C virus does not infect peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1843–1850.

- Dustin, L.B. Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in Chronic HCV Infection. Curr. Drug Targets 2017, 18, 826–843.

- Dolganiuc, A.; Kodys, K.; Kopasz, A.; Marshall, C.; Mandrekar, P.; Szabo, G. Additive inhibition of dendritic cell allostimulatory capacity by alcohol and hepatitis C is not restored by DC maturation and involves abnormal IL-10 and IL-2 induction. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 27, 1023–1031.

- Sarobe, P.; Lasarte, J.J.; Zabaleta, A.; Arribillaga, L.; Arina, A.; Melero, I.; Borras-Cuesta, F.; Prieto, J. Hepatitis C virus structural proteins impair dendritic cell maturation and inhibit in vivo induction of cellular immune responses. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10862–10871.

- Szabo, G.; Dolganiuc, A. Subversion of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cell functions in chronic HCV infection. Immunobiology 2005, 210, 237–247.

- Marrack, P.; McKee, A.S.; Munks, M.W. Towards an understanding of the adjuvant action of aluminium. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 287–293.

- Georg, P.; Sander, L.E. Innate sensors that regulate vaccine responses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2019, 59, 31–41.

- Gutjahr, A.; Tiraby, G.; Perouzel, E.; Verrier, B.; Paul, S. Triggering Intracellular Receptors for Vaccine Adjuvantation. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 573–587.

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 343–353.

- Pulendran, B. The varieties of immunological experience: Of pathogens, stress, and dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 563–606.

- Vasou, A.; Sultanoglu, N.; Goodbourn, S.; Randall, R.E.; Kostrikis, L.G. Targeting Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRR) for Vaccine Adjuvantation: From Synthetic PRR Agonists to the Potential of Defective Interfering Particles of Viruses. Viruses 2017, 9, 186.

- Dowling, J.K.; Mansell, A. Toll-like receptors: The swiss army knife of immunity and vaccine development. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2016, 5, e85.

More